Shanghai Animation Attracts Hollywood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Step Over to the Asian Side Yves Jeanneau Reveals That the Future of Documentary Points to Asia a Dynamic Professional Directory &Network Tool

March/April 2013 | Vol. 011 www.mediahubaccess.com INTERVIEW Alexandre Muller, Managing Director discusses new media developments at TV5Monde Asia COMPANY FOCUS CEO, Francois-Xavier Poirier, gives a glimpse of the stories behind the laughs at Novovision Step over to the Asian side Yves Jeanneau reveals that the future of documentary points to Asia A dynamic professional directory &network tool Looking for a fixer, a co-producer or OB van rental? Mediahub PROlink gives you access to all the contacts you need to plan any type of production in the world: Browse an extensive database of key contacts facilitating the organization of your production onsite: production studios, services, crews and facilities Join an international production, distribution and broadcast community where you can maximize your visibility, connect with other members and open up new business opportunities. Post any business related news through the Mediahub Message Board and spread the info to the entire Mediahub network. mediahubaccess.com EDITORIAL Director of Publication ransitions can be daunting. Al- as a prominent stop for producers Dimitri Mendjisky though most of the time it is a and documentary makers, the progression towards something time has arrived to step over to General Manager T better, not all of us are ready to the Asian side! Juliette Vivier embrace the change that follows. But, a transition is an important In our Interview of the month, EDITORIAL facet to a musical arrangement; TV5Monde’s Managing Direc- Editor-In-Chief a smooth segue from one move- tor, Alexandre Muller, is all about Suzane Avadiar ment to another is as vital as each the growth within the company. -

On the Rise and Decline of Wulitou 无厘头's Popularity in China

The Act of Seeing and the Narrative: On the Rise and Decline of Wulitou 无厘头’s Popularity in China Inaugural dissertation to complete the doctorate from the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne in the subject Chinese Studies presented by Wen Zhang ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks go to my supervisors, Prof. Dr. Stefan Kramer, Prof. Dr. Weiping Huang, and Prof. Dr. Brigitte Weingart for their support and encouragement. Also to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne for providing me with the opportunity to undertake this research. Last but not least, I want to thank my friends Thorsten Krämer, James Pastouna and Hung-min Krämer for reviewing this dissertation and for their valuable comments. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 1 0.1 Wulitou as a Popular Style of Narrative in China ........................................................... 1 0.2 Story, Narrative and Schema ................................................................................................. 3 0.3 The Deconstruction of Schema in Wulitou Narratives ................................................... 5 0.4 The Act of Seeing and the Construction of Narrative .................................................... 7 0.5 The Rise of the Internet and Wulitou Narrative .............................................................. 8 0.6 Wulitou Narrative and Chinese Native Cultural Context .......................................... -

07Cmyblookinside.Pdf

2007 China Media Yearbook & Directory WELCOMING MESSAGE ongratulations on your purchase of the CMM- foreign policy goal of China’s media regulators is to I 2007 China Media Yearbook & Directory, export Chinese culture via TV and radio shows, films, Cthe most comprehensive English resource for books and other cultural products. But, of equal im- businesses active in the world’s fastest growing, and portance, is the active regulation and limitation of for- most complicated, market. eign media influence inside China. The 2007 edition features the same triple volume com- Although the door is now firmly shut on the establish- bination of CMM-I independent analysis of major de- ment of Sino-foreign joint venture TV production com- velopments, authoritative industrial trend data and panies, foreign content players are finding many other fully updated profiles of China’s major media players, opportunities to actively engage with the market. but the market described has once again shifted fun- damentally on the inside over the last year. Of prime importance is the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympiad. At no other time in Chinese history have so Most basically, the Chinese economic miracle contin- many foreign media organizations engaged in co- ued with GDP growth topping 10 percent over 2005-06 production features exploring the modern as well as and, once again, parts of China’s huge and diverse old China. But while China has relaxed its reporting media industry continued to expand even faster over procedures for the duration, it would be naïve to be- the last twelve months. lieve this signals any kind of fundamental change in the government’s position. -

IMAX CHINA HOLDING, INC. (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 1970)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. IMAX CHINA HOLDING, INC. (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 1970) BUSINESS UPDATE WANDA CINEMA LINE CORPORATION LIMITED AGREES TO ADD 150 IMAX THEATRES The board of directors of IMAX China Holding, Inc. (the “Company”) announces that the Company (through its subsidiaries) has entered into an agreement (“Installation Agreement”) with Wanda Cinema Line Corporation Limited (“Wanda Cinema”). Under the Installation Agreement, 150 IMAX theatres will be built throughout China over six years, starting next year. With the Installation Agreement, the Company’s total number of theatre signings year to date has reached 229 in China and the total backlog will increase nearly 60 percent. The Installation Agreement is in addition to an agreement entered into between the Company and Wanda Cinema in 2013 (“Previous Installation Agreement”). Under the Previous Installation Agreement, Wanda Cinema committed to deploy 120 new IMAX theatres by 2020. The key commercial terms of the Installation Agreement are substantially similar to those under the Previous Installation Agreement. The Company made a press release today regarding the Installation Agreement. For -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Uncertain Satire in Modern Chinese Fiction and Drama: 1930-1949 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Xi Tian August 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Perry Link, Chairperson Dr. Paul Pickowicz Dr. Yenna Wu Copyright by Xi Tian 2014 The Dissertation of Xi Tian is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Uncertain Satire in Modern Chinese Fiction and Drama: 1930-1949 by Xi Tian Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Comparative Literature University of California, Riverside, August 2014 Dr. Perry Link, Chairperson My dissertation rethinks satire and redefines our understanding of it through the examination of works from the 1930s and 1940s. I argue that the fluidity of satiric writing in the 1930s and 1940s undermines the certainties of the “satiric triangle” and gives rise to what I call, variously, self-satire, self-counteractive satire, empathetic satire and ambiguous satire. It has been standard in the study of satire to assume fixed and fairly stable relations among satirist, reader, and satirized object. This “satiric triangle” highlights the opposition of satirist and satirized object and has generally assumed an alignment by the reader with the satirist and the satirist’s judgments of the satirized object. Literary critics and theorists have usually shared these assumptions about the basis of satire. I argue, however, that beginning with late-Qing exposé fiction, satire in modern Chinese literature has shown an unprecedented uncertainty and fluidity in the relations among satirist, reader and satirized object. -

Shanghai and Beijing Travel Report 2010

Shanghai International Film Festival and Market, Shanghai and Beijing meetings Report by Chris Oliver and Ross Matthews To report that the China screen landscape is undergoing change is not new news. All facets of the screen industry development, production, distribution, exhibition and broadcasting are going through change – a change that is in a positive direction. The change in the way the Chinese industry is engaging with the rest of world’s screen industries, including the way Government instrumentalities are relating to other countries (eg treaties) will be of real benefit to the Chinese and the international screen industry. Australia is well placed to benefit from those changes if (that’s capital IF) Australian producers/players understand the rules of engagement with Chinese producers, broadcasters and exhibitors and the Chinese government departments involved in implementing government policy. Why should Australia engage with China? There are obvious commercial reasons. Firstly, the Chinese gross box office (GBO) has increased by at least 30 per cent in the last year to US$909 million – and has now surpassed Australia to be number six in the world. According to those we had discussions with in China and what can be gleaned from the screen press, the China GBO will grow by at least a further 40 per cent in the 2010 calendar year! Secondly, China’s population has an ever-increasing level of Abbreviations disposable income to underpin AIDC Australian International Documentary Conference the cinema ticket price of $6–10: CCTV China Central Television TRAVELREPORT it’s been reported that middle CFCC China Film Co-production Corporation class numbers will exceed those CFGC China Film Group Corporation in the US by 2020. -

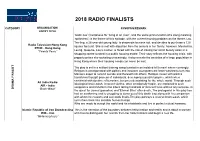

2018 Radio Finalists

2018 RADIO FINALISTS CATEGORY ORGANISATION/ SYNOPSIS/REMARK ENTRY TITLE ‘Gook Jue’ (Cantonese for ‘living in an oven’, and the same pronunciation of a slang meaning ‘optionless’) is the theme of this episode, with the current housing problem as the theme. Lau, Tse-ling, a 28-year-old young lady, is desperate to move out, and decides to purchase a 128 Radio Television Hong Kong square feet unit. She is met with objection from the seniors in her family, however. Meanwhile, RTHK - Hong Kong “Twenty Years” Leung, Queenie, Lau’s mother, is faced with the risk of closing her small beauty salon in a shopping centre located in a public housing estate. Their story reflects the housing crisis, with property prices sky-rocketing unceasingly; it also reveals the anxieties of a large population in Hong Kong where their housing needs can never be met. The play is set in a militant training camp located in an isolated hill terrain' where cunningly, Religion is amalgamated with politics and innocent youngsters are brain-washed to turn into Maniacs eager to commit suicide and therewith kill others. Religion mixed with politics FINALIST transforms thought process of individuals, developing a parallel psyche, which when combined with doctrine of terrorism, becomes devastating for the whole world. Through such All India Radio ideological brain-wash, innocent victims, often emotionally fragile, are exploited to seek AIR - India vengeance and transform into killers taking hundreds of innocent lives without any remorse, in DRAMA “Brain-Wash” the quest for Jannat (paradise) and 'Eternal Bliss' after death, The protagonist in this play has had an awakening and is struggling to come out of this death trap along with his companion with whom he reasons and succeeds finally.The play portrays a reverse brain-wash, which turns them back into sensible human beings Who are ready to accept the world and its inhabitants and live in perfect mutual harmony. -

Media Oligarchs Go Shopping Patrick Drahi Groupe Altice

MEDIA OLIGARCHS GO SHOPPING Patrick Drahi Groupe Altice Jeff Bezos Vincent Bolloré Amazon Groupe Bolloré Delian Peevski Bulgartabak FREEDOM OF THE PRESS WORLDWIDE IN 2016 AND MAJOR OLIGARCHS 2 Ferit Sahenk Dogus group Yildirim Demirören Jack Ma Milliyet Alibaba group Naguib Sawiris Konstantin Malofeïev Li Yanhong Orascom Marshall capital Baidu Anil et Mukesh Ambani Rupert Murdoch Reliance industries ltd Newscorp 3 Summary 7. Money’s invisible prisons 10. The hidden side of the oligarchs New media empires are emerging in Turkey, China, Russia and India, often with the blessing of the political authorities. Their owners exercise strict control over news and opinion, putting them in the service of their governments. 16. Oligarchs who came in from the cold During Russian capitalism’s crazy initial years, a select few were able to take advantage of privatization, including the privatization of news media. But only media empires that are completely loyal to the Kremlin have been able to survive since Vladimir Putin took over. 22. Can a politician be a regular media owner? In public life, how can you be both an actor and an objective observer at the same time? Obviously you cannot, not without conflicts of interest. Nonetheless, politicians who are also media owners are to be found eve- rywhere, even in leading western democracies such as Canada, Brazil and in Europe. And they seem to think that these conflicts of interests are not a problem. 28. The royal whim In the Arab world and India, royal families and industrial dynasties have created or acquired enormous media empires with the sole aim of magnifying their glory and prestige. -

Independent Cinema in the Chinese Film Industry

Independent cinema in the Chinese film industry Tingting Song A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology 2010 Abstract Chinese independent cinema has developed for more than twenty years. Two sorts of independent cinema exist in China. One is underground cinema, which is produced without official approvals and cannot be circulated in China, and the other are the films which are legally produced by small private film companies and circulated in the domestic film market. This sort of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has played a significant role in the development of Chinese cinema in terms of culture, economics and ideology. In contrast to the amount of comment on underground filmmaking in China, the significance of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has been underestimated by most scholars. This thesis is a study of how political management has determined the development of Chinese independent cinema and how Chinese independent cinema has developed during its various historical trajectories. This study takes media economics as the research approach, and its major methods utilise archive analysis and interviews. The thesis begins with a general review of the definition and business of American independent cinema. Then, after a literature review of Chinese independent cinema, it identifies significant gaps in previous studies and reviews issues of traditional definition and suggests a new definition. i After several case studies on the changes in the most famous Chinese directors’ careers, the thesis shows that state studios and private film companies are two essential domestic backers for filmmaking in China. -

Reddening Or Reckoning?

Reddening or Reckoning? An Essay on China’s Shadow on Hong Kong Media 22 Years after Handover from British Rule Stuart Lau Journalist Fellow 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism University of Oxford August 2019 CONTENTS 1. Preface 2 2. From top to bottom: the downfall of a TV station 4 3. Money, Power, Media 10 4. “Political correctness”: New normal for media 20 5. From the Big Brother: “We are watching you” 23 6. Way forward - Is objective journalism still what Hong Kong needs? 27 1 Preface Hong Kong journalists have always stood on the front line of reporting China, a country that exercises an authoritarian system of government but is nonetheless on track to global economic prominence. The often-overlooked role of Hong Kong journalists, though, has gained international attention in summer 2019, when weeks of citywide protests has viralled into the largest-scale public opposition movement ever in the city’s 22-year history as a postcolonial political entity under Chinese sovereignty, forcing the Hong Kong government into accepting defeat over the hugely controversial extradition bill. While much can be said about the admirable professionalism of Hong Kong’s frontline journalists including reporters, photojournalists and video journalists, most of whom not having received the level of warzone-like training required amid the police’s unprecedentedly massive use of potentially lethal weapons, this essay seeks to examine something less visible and less discussed by international media and academia: the extent to which China influences Hong Kong’s media organisations, either directly or indirectly. The issue is important on three levels. -

Platform Delegate List

First Name Surname Job Title Company Email Suleeko Abdi Student [email protected] Frances Abebreseh Communications Manager Netflix Lucy Acfield Head of Brand & Product Marketing Guinness World Records James Acken Founder, Freelancer Acken Studios lindsey@dailymadnessproducti Lindsey Adams Producer Daily Madness ons.com Megan Adams Look Mentor Look UK ToyLikeMe Seleena Addai Illustrator / Character Designer The Secret Story Draw [email protected] Animation Production Liaison [email protected] Abigail Addison Executive ScreenSkills om Aiden Adkin Creative Director Harbour Bay [email protected] Selorm Adonu Director XVI Films [email protected] Ivan Agenjo Executive Producer Peekaboo Animation [email protected] Jayne Aguire Walsh Entry Level Creative Freelance [email protected] Andrew Aidman Producer Andrew Aidman [email protected] Sun In Eye Productions, Aittokoski Metsamarja Aittokoski Screenwriter, Director, Producer Experience [email protected] Sonja Ajdin Research Manager Viacom Yinka Akano CRBA Exec BBC [email protected] Production and Development Francesca Alberigi Coordinator Nickelodeon International Aoife Alder Research Executive ITV Candice Alessandra Student Student Laura Alexander Video Producer / Editor Acamar Films Kristopher Alexander Professor of Video Games The Digital Citadel [email protected] Lisa Ali Freelance Freelance Shakila Ali Content Impact BBC Co-Founder and Chief Creative Caroline Allams Officer Natterhub [email protected] Bill Allard -

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings TITLE PUBLICATION INFORMATION NUMBER DATE LANG 1-800-INDIA Mitra Films and Thirteen/WNET New York producer, Anna Cater director, Safina Uberoi. VD-1181 c2006. eng 1 giant leap Palm Pictures. VD-825 2001 und 1 on 1 V-5489 c2002. eng 3 films by Louis Malle Nouvelles Editions de Films written and directed by Louis Malle. VD-1340 2006 fre produced by Argosy Pictures Corporation, a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture [presented by] 3 godfathers John Ford and Merian C. Cooper produced by John Ford and Merian C. Cooper screenplay VD-1348 [2006] eng by Laurence Stallings and Frank S. Nugent directed by John Ford. Lions Gate Films, Inc. producer, Robert Altman writer, Robert Altman director, Robert 3 women VD-1333 [2004] eng Altman. Filmocom Productions with participation of the Russian Federation Ministry of Culture and financial support of the Hubert Balls Fund of the International Filmfestival Rotterdam 4 VD-1704 2006 rus produced by Yelena Yatsura concept and story by Vladimir Sorokin, Ilya Khrzhanovsky screenplay by Vladimir Sorokin directed by Ilya Khrzhanovsky. a film by Kartemquin Educational Films CPB producer/director, Maria Finitzo co- 5 girls V-5767 2001 eng producer/editor, David E. Simpson. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. ita Flaiano, Brunello Rondi. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987.