Taxonomy and Its Pleasures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Journal Banisteria Is Named for a Naturalist Whose Virginia Collections Have Been Know to Many Botanists Only Through the Ci

Banisteria, Number 1, 1992 © 1992 by the Virginia Natural History Society John Banister, Virginia’s First Naturalist Joseph and Nesta Ewan Missouri Botanical Garden St. Louis, Missouri 63166 The journal Banisteria is named for a naturalist became particularly important to Banister for arranging whose Virginia collections have been known to many for the import of drawing materials, paper, gum arabic, botanists only through the citations in Linnaeus’ Species and books. Ordering from such a distance had its dis- plantarum as Ray, hist., Pluk. alm. or phyt., or Moris. advantages. As an example, on 8 August 1690 Byrd hist. The Reverend John Banister (1650-1692) was wrote to a London dealer, “I wonder you doe not So Virginia’s first university-trained naturalist. At the age of much as mention mr Banister’s mony, though he gave seventeen he had shown abilities and interests which me an Order for all in your hands (Which I know you earned him a scholarship as a chorister at Magdalen recd) so that is impossible for mee to reckon with mr College, Oxford University. Although he was in training Banister.” On 25 October he wrote again: “pray lett mee as a minister in the Anglican Church, he soon discovered know what money you have recd & given credit for, on nearby Oxford Physick Garden with its plants from much Mr Banisters account that hee & I may be able to of the known world, and took particular interest in those Reckon.” from America. He attended Professor Robert Morison’s In his letter written from “The Falls Apr. -

Plants Found in the Middle Parts of the State Grow Here, Excepting the Alpine Flowers

CULTIVATION BOTANY.— Wood grows here [Concord] with great rapidity; and it is supposed there is as much now as there was twenty years ago. Walden woods at the south, and other lots towards the southwest parts of the town, are the most extensive, covering several hundred acres of light-soil land. Much of the fuel, which is consumed, is, however brought from the neighbouring towns. The most common trees are the oak, pine, maple, elm, white birch, chestnut, walnut, &c., &c. Hemlock and spruce are very rare. The ornamental trees transplanted, in this as in most other towns, do not appear to have been placed with much regularity; but as they are, they contribute much to the comfort and beauty of the town. The elm, buttonwood, horse-chestnut, and fruit trees have very properly taken the place of sickly poplars, in ornamenting the dwellings. The large elm in front of the court-house, –the pride of the common,– is almost unrivalled in beauty. It is about “three score and ten,” but is still growing with youthful vigor and uniform rapidity. Dr. Jarvis, who is familiar with the botany of Concord, informs me, that “most of the plants found in the middle parts of the state grow here, excepting the alpine flowers. The extensive low lands produce abundantly the natural families of the aroideæ, typhæ, cyperoideæ, gramineæ, junci, corymbiferæ and unbelliferæ. These genera especially abound. There are also found, the juncus militaris (bayonet rush), on the borders of Fairhaven pond; cornus florida; lobelia carinalis (cardinal flower) abundant on the borders of the river; polygala cruciata, in the east parts of the town; nyssa villosa (swamp hornbeam) at the foot of Fairhaven hill.” The cicuta Americana (hemlock) grows abundant on the intervals. -

Linnaeus' Philosophia Botanica

linnaeus’ Philosophia Botanica STEPHEN FREER Stephen Freer, born at Little Compton in1920, was a classical scholar at Eton and Trinity College Cambridge. In 1940, he was approached by the Foreign Office and worked at Bletchley Park and in London. Later, Stephen was employed by the Historical Manuscripts Commission, retiring in 1962 due to ill health. He has continued to work since then, first as a volunteer for the MSS department of the Bodleian Library with Dr William Hassall, and then on a part-time basis at the Oxfordshire County Record. In 1988, he was admitted as a lay reader in the Diocese of Oxford. His previous book was a translation of Wharton’s Adenographia, published by OUP in 1996. A fellow of the Linneau Society of London, Stephen lives with his wife Frederica in Gloucestershire. They have a daughter, Isabel. COVER ILLUSTRATION Rosemary Wise, who designed and painted the garland of flowers on the book cover, is the botanical illustrator in the Department of Plant Sciences in the University of Oxford, associate staff at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and a fellow of the Linneau Society of London. In1932 Carl Linnaeus made an epic journey to Lapland, the vast area across arctic Norway, Sweden, and Finland. In 1988, to mark the bicentenary of the Linneau Society of London, a group from Great Britain and Sweden retraced his route. Rosemary, was the official artist and the flowers featured here are taken from ones painted at that time, plants with which Linnaeus would have been familiar. The garland of flowers surrounds an image of the medallion portrait of Linnaeus by C. -

Roots to Seeds Exhibition Large Print Captions

LARGE PRINT CAPTIONS ROOTS TO SEEDS 400 YEARS OF OXFORD BOTANY PLEASE RETURN AFTER USE Curator’s audio guide Listen to Professor Stephen Harris explore highlights from the exhibition. To access the audio guide, use your mobile device to log in to ‘Weston-Public-WiFi’. Once connected, you can scan the QR code in each case, or go to visit.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/rootsaudio To listen to the exhibition introduction scan this QR code You are welcome to use your device with or without headphones. Plants are essential to all aspects of our lives. They feed, clothe and shelter us, and provide us with drugs, medicine and the oxygen we need to survive. Moreover, they have key roles in resolving current global problems such as food security, environmental change and sustainable development. This summer marks the anniversary of the foundation of the Oxford Botanic Garden, in 1621, and offers an opportunity to reflect on four centuries of botanical research and teaching in the University. Botany in Oxford, as we will see in this exhibition, has not enjoyed steady growth. Activity has been patchy; long periods of relative torpor, punctuated by bursts of intensely productive activity. The professors and researchers who have worked in Oxford have contributed to startling advances in our knowledge of plants, but they also found themselves held back by circumstance – their own, the societies in which they lived, or by the culture of the University. The roots of Oxford botany are in its collections of specimens and books, which remain central to modern teaching and research. -

Utopian Order and Rebellion in the Oxford Physick Garden Annals of Science

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Annals of Science. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Svensson, A. [Year unknown!] ‘And Eden from the Chaos rose’:: utopian order and rebellion in the Oxford Physick Garden Annals of Science https://doi.org/10.1080/00033790.2019.1641223 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-255821 Annals of Science ISSN: 0003-3790 (Print) 1464-505X (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tasc20 ‘And Eden from the Chaos rose’: utopian order and rebellion in the Oxford Physick Garden Anna Svensson To cite this article: Anna Svensson (2019): ‘And Eden from the Chaos rose’: utopian order and rebellion in the Oxford Physick Garden, Annals of Science, DOI: 10.1080/00033790.2019.1641223 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00033790.2019.1641223 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 24 Jul 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 172 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tasc20 ANNALS OF SCIENCE https://doi.org/10.1080/00033790.2019.1641223 ‘And Eden from the Chaos rose’: utopian order and rebellion in the Oxford Physick Garden Anna Svensson School of Architecture and the Built Environment, Division of History of Science, Technology and Environment, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Abel Evans’s poem Vertumnus (1713) celebrates Jacob Bobart Received 4 July 2019 the Younger, second keeper of the Oxford Physick Garden Accepted 4 July 2019 (now the Oxford University Botanic Garden), as a model KEYWORDS monarch to his botanical subjects. -

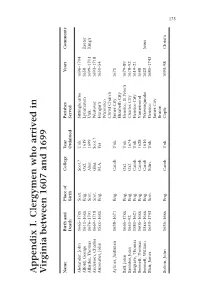

Appendix I. Clergymen Who Arrived in V Irginia Between 1607 and 1699

Appendix I. Clergymen who arrived in Virginia between 1607 and 1699 Name Birth and Place of College Year Parishes Years Comments Death Birth Ordained Served Alexander, John 1665–17xx Scot. Scot.? Unk. Sittingbourne 1696–1704 Alford, George 1611–16xx Eng. Oxf. 1619 Lynnhaven 1658 Exeter Allardes, Thomas 1676–1701 Scot. Aber. 1699 Unk. 1699–1701 King’s Anderson, Charles 1669–1718 Scot. Glas. Scot.? Westover 1693–1718 Armourier, John 15xx–16xx Eng. M.A. Yes Hungar’s 1651–54 Wicomico Christ Church Aylmer, Justinian 1638–1671 Eng. Camb. Unk. James City 1671 Elizabeth City Ball, John 1665–17xx Eng. Oxf. Unk. Henrico, St Peter’s 1679–89 Banister, John 1650–92 Eng. Oxf. 1674 Charles City 1678–92 Bargrave, Thomas 1581–1621 Eng. Camb. Unk. Henrico City 1619–21 Bennett, Thomas 1605–16xx Eng. Camb. 1628 Nansemond 1648 Bennett, William 15xx–16xx Eng. Camb 1616 Warwisqueake 1623 Jesus Blair, James 1653–1743 Scot. Edin. Unk. Henrico 1685–1743 James City Bruton Bolton, John 1635–16xx Eng. Camb. Unk. Cople 1693–98 Christ’s 175 176 (Continued) Name Birth and Place of College Year Parishes Years Comments Death Birth Ordained Served Bolton, Francis 1595–16xx Eng. Camb. Unk. Elizabeth City 1621–30 Accomac? 1623–26 Warwisqueake Bowker, James 1665–1703 Eng. Camb. Unk. Kempton 1690–1703 St Peter’s Bracewell, Robert 1611–68 Eng. Oxf. Unk. Isle of Wight 1653–68d. Bucke, Richard 1584–1623 Eng. Camb. Unk. James City 1610–23 Bushnell, James 16xx–17xx Unk. Unk. Unk. Martin’s Hundred 1696–1702 Butler, William 1647–17xx Eng. Camb. Unk. -

John Banister, Virginia’S First Naturalist

Banisteria, Number 1, 1992 © 1992 by the Virginia Natural History Society John Banister, Virginia’s First Naturalist Joseph and Nesta Ewan Missouri Botanical Garden St. Louis, Missouri 63166 The journal Banisteria is named for a naturalist became particularly important to Banister for arranging whose Virginia collections have been know to many for the import of drawing materials, paper, gum arabic, botanists only through the citations in Linnaeus’ Species and books. Ordering from such a distance had its dis- plantarum as Ray hist., Pluk. alm. or phyt, or Moris. advantages. As an example, on 8 August 1690 Byrd hist. The Reverend John Banister (1650-1692) was wrote to a London dealer, “I wonder you doe not So Virginia’s first university-trained naturalist. At the age of much as mention mr Banister’s mony, though he gave seventeen he had shown abilities and interests which me an Order for all in your hands (Which I know you earned him a scholarship as a chorister at Magdalen recd) so that is impossible for mee to reckon with mr College, Oxford University. Although he was in training Banister.” On 25 October he wrote again: “pray lett mee as a minister in the Anglican Church, he soon discovered know what money you have recd & given credit for, on nearby Oxford Physick Garden with its plants from much Mr Banisters account that hee & I may be able to of the known world, and took particular interest in those Reckon.” from America. He attended Professor Robert Morison’s In his letter written from “The Falls Apr. -

James Petiver Promoter of Natural Science, C.1663-1718

James Petiver Promoter of Natural Science, c.1663-1718 BY RAYMOND PHINEAS STEARNS 3R upwards of thirty years after 1685 James Petiver Fwas the proprietor of an apothecary shop "at the sign of the White Cross in Aldersgate Street, London." During these years this address became familiar to brother apothe- caries, shipmasters, merchants, planters, physicians, , sur- geons, ministers of the gospel, consuls, ambassadors, privy councilors, peers of the realm, and foreign gentlemen of various degrees extending from Moscow to the Cape of Good Hope and from the British Colonies in the New World to the Spanish settlements in the Philippines. From this shop were dispatched thousands of letters and queries, occasional bits of medical advice together with shipments of drugs and nostrums, newssheets, scientific pamphlets and books, frequent consignments of brown paper, wide-mouthed bottles, and detailed instructions for amateur naturalists and collectors who had set forth—or were on the point of setting forth—to nearby English counties or to far-off foreign lands. To this shop were addressed other thousands of queries—most of them per- taining to the scientific identification, description, classifica- tion, use, habitat, collection, and preservation of botanical specimens and other items of natural history—and hundreds of consignments of seeds, dried plants, insects, serpents, birds, fishes, and small animals for the collections of Mr. Petiver and his friends, whose appetites for such things were insatiable. In this shop were assembled, besides the stocks of herbs and medicines common to a busy and prosperous 244 AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY [Oct., apothecary, one of the largest and most varied collections of specimens of the natural history of the world that existed in England during the early years of the eighteenth century. -

The Names of Plants, Third Edition

THE NAMES OF PLANTS The Names of Plants is a handy, two-part reference book for the botanist and amateur gardener. The book begins by documenting the historical problems associated with an ever-increasing number of common names of plants and the resolution of these problems through the introduction of International Codes for both botanical and horticultural nomenclature. It also outlines the rules to be followed when plant breeders name a new species or cultivar of plant. The second part of the book comprises an alphabetical glossary of generic and specific plant names, and components of these, from which the reader may interpret the existing names of plants and construct new names. For the third edition, the book has been updated to include explanations of the International Codes for both Botanical Nomen- clature (2000) and Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (1995). The glossary has similarly been expanded to incorporate many more commemorative names. THE NAMES OF PLANTS THIRD EDITION David Gledhill Formerly Senior Lecturer, Department of Botany, University of Bristol and Curator of Bristol University Botanic Garden Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , United Kingdom Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521818636 © Cambridge University Press 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of -

“Being a Method Proposed for the Ready Finding…To What Sort Any Plant Belongeth”

Oklahoma Native Plant Record 77 Volume 10, December 2010 “BEING A METHOD PROPOSED FOR THE READY FINDING…TO WHAT SORT ANY PLANT BELONGETH” Ronald J. Tyrl Emeritus Professor of Botany Department of Botany Oklahoma State University As any ONPS member will attest, it species name. Sometimes my first try is doesn‟t take many field trips into the prairies successful, but more often I have to make and forests of Oklahoma to encounter an several or even numerous attempts. However, unknown plant and have to ask, “What is it?” nothing is more satisfying than to be able to The easiest way to identify it is disarmingly say “Gotcha! I know who you are!” In the simple; ask someone who knows! This following essay, I offer an overview of the approach works well when an expert is near at origins and evolution of taxonomic keys, hand, ready to name plants. A second aspects of their nature, and suggestions on approach is to compare the unknown plant how to use them successfully. with photographs or illustrations in field guides specific for Oklahoma. Unfortunately, Origins and Evolution of the Key— the major drawbacks in using such guides are Taxonomic keys have been the mainstays of that they typically illustrate only showy- plant identification for more than 250 years. flowered species and may not include all Their origins, however, are considerably older species present in the area. The ideal way to and can be traced to the classifications of identify an unknown plant is to use a Aristotle and Theophrastus, based on taxonomic key – an artificial analytical device fundamentum divisionis or the “principle of for identification which offers a progressive division” and those of 17th Century series of choices between pairs of alternative naturalists (Voss 1952; Stuessy 1990). -

HUNTIA a Journal of Botanical History

HUNTIA A Journal of Botanical History VOLUME 16 NUMBER 2 2018 Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh The Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, a research division of Carnegie Mellon University, specializes in the history of botany and all aspects of plant science and serves the international scientific community through research and documentation. To this end, the Institute acquires and maintains authoritative collections of books, plant images, manuscripts, portraits and data files, and provides publications and other modes of information service. The Institute meets the reference needs of botanists, biologists, historians, conservationists, librarians, bibliographers and the public at large, especially those concerned with any aspect of the North American flora. Huntia publishes articles on all aspects of the history of botany, including exploration, art, literature, biography, iconography and bibliography. The journal is published irregularly in one or more numbers per volume of approximately 200 pages by the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation. External contributions to Huntia are welcomed. Page charges have been eliminated. All manuscripts are subject to external peer review. Before submitting manuscripts for consideration, please review the “Guidelines for Contributors” on our Web site. Direct editorial correspondence to the Editor. Send books for announcement or review to the Book Reviews and Announcements Editor. All issues are available as PDFs on our Web site. Hunt Institute Associates may elect to receive Huntia as a benefit of membership; contact the Institute for more information. Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Carnegie Mellon University 5th Floor, Hunt Library 4909 Frew Street Pittsburgh, PA 15213-3890 Telephone: 412-268-2434 Email: [email protected] Web site: http://www.huntbotanical.org Editor and layout Scarlett T. -

John Tayler, College Gardener, D. 1686, and a Library of Botanical Books the Science of Plants

Early Science in New College III: John Tayler, College Gardener, d. 1686, and a Library of Botanical Books The science of plants in the early modern period was not quite modern Plant Sciences. The most common kind of serious engagement with plants was the practice of ‘simpling’, or the identification and gathering of medicinal plants. This was rooted in the work of the ancient Greek botanist and pharmacist Dioscorides, and the college owns seven early editions of his De materia medica, an early pharmacopeia. But there were new initiatives in the early modern period both to improve the taxonomy and to investigate the structure and physiology of plants, and in Britain these culminated in the work of later seventeenth-century scientists such as Robert Hooke, John Ray, Robert Morison, and Nehemiah Grew. In Oxford, the study of these related areas was put on an institutional footing by the founding in 1621 of the Botanic Garden, which only acquired its own salaried Curator in the early 1640s. There was plenty of informal activity in the colleges, however, and in New College, two names have traditionally stood out: those of the simpler William Coles (1626–1662), who matriculated in 1642 but migrated to Merton as a Postmaster in 1650; and of the lawyer, churchman, and botanist Robert Sharrock (1630– 1684, matr. 1650, BCL 1654, DCL 1661), who had a much longer college career, and who also served as the college librarian for the first half of the 1660s. Sharrock published a number of works in different disciplines, but his major work in plant science was The History of the Propagation and Improvement of Vegetables, published in Oxford in 1660, with later editions of 1666 and 1672.1 I shall leave discussions of these men for another time, but in his Art of Simpling (1656), Coles recorded a vignette about Warden Pincke of New College (1573–1647) in his garden: Dr.