HUNTIA a Journal of Botanical History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Add a Tuber to the Pod: on Edible Tuberous Legumes

LEGUME PERSPECTIVES Add a tuber to the pod: on edible tuberous legumes The journal of the International Legume Society Issue 19 • November 2020 IMPRESSUM ISSN Publishing Director 2340-1559 (electronic issue) Diego Rubiales CSIC, Institute for Sustainable Agriculture Quarterly publication Córdoba, Spain January, April, July and October [email protected] (additional issues possible) Editor-in-Chief Published by M. Carlota Vaz Patto International Legume Society (ILS) Instituto de Tecnologia Química e Biológica António Xavier Co-published by (Universidade Nova de Lisboa) CSIC, Institute for Sustainable Agriculture, Córdoba, Spain Oeiras, Portugal Instituto de Tecnologia Química e Biológica António Xavier [email protected] (Universidade Nova de Lisboa), Oeiras, Portugal Technical Editor Office and subscriptions José Ricardo Parreira Salvado CSIC, Institute for Sustainable Agriculture Instituto de Tecnologia Química e Biológica António Xavier International Legume Society (Universidade Nova de Lisboa) Apdo. 4084, 14080 Córdoba, Spain Oeiras, Portugal Phone: +34957499215 • Fax: +34957499252 [email protected] [email protected] Legume Perspectives Design Front cover: Aleksandar Mikić Ahipa (Pachyrhizus ahipa) plant at harvest, [email protected] showing pods and tubers. Photo courtesy E.O. Leidi. Assistant Editors Svetlana Vujic Ramakrishnan Nair University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Agriculture, Novi Sad, Serbia AVRDC - The World Vegetable Center, Shanhua, Taiwan Vuk Đorđević Ana María Planchuelo-Ravelo Institute of Field and Vegetable Crops, Novi Sad, Serbia National University of Córdoba, CREAN, Córdoba, Argentina Bernadette Julier Diego Rubiales Institut national de la recherche agronomique, Lusignan, France CSIC, Institute for Sustainable Agriculture, Córdoba, Spain Kevin McPhee Petr Smýkal North Dakota State University, Fargo, USA Palacký University in Olomouc, Faculty of Science, Department of Botany, Fred Muehlbauer Olomouc, Czech Republic USDA, ARS, Washington State University, Pullman, USA Frederick L. -

Botoșani County)

Analele Ştiinţifice ale Universităţii „Al. I. Cuza” Iaşi http://www.bio.uaic.ro/publicatii/anale_vegetala/anale_veg_index.html s. II a. Biologie vegetală, 2020, 66: 13-29 ISSN: 1223-6578, E-ISSN: 2247-2711 ASPECTS REGARDING FLORA AND THE ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF SOME PLANT SPECIES FROM THE LOCAL MEADOWS OF BĂICENI (BOTOȘANI COUNTY) Florentina ȘCHIOPU1, Anișoara STRATU2*, Irina IRIMIA2 Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to inventory the plant species in the meadows on the territory of Băiceni and highlight their economic importance. The floristic studies were carried out in the vegetation season from 2018 to 2019. Based on the literature, plant species were identified and then processed in terms of bioforms, floristic elements and ecological indices. Also, the economic categories in which the identified species fall were analysed. 66 species belonging to 21 botanical families have been identified. The families Fabaceae, Poaceae and Asteraceae were distinguished by the higher number of species. Most of the species identified in the study area are hemicryptophytes, heliophiles, eurytherms, which grow on dry to moderately moist soils, euritrophs. Over 50% of the identified species belong to several categories of useful plants (fodder, medicinal, melliferous). Keywords: flora, meadows, bioforms, floristic elements, ecological indices, economic categories. Introduction In Romania, in 2014, hayfields and pastures occupied 31.9% of the country's agricultural area (Raport anual privind starea mediului în România, anul 2017). In Botoșani County, at the level of 2019, pastures, hayfields and natural meadows represented 23% of the agricultural area of the county, the pastures having a higher share (19%) (Raport privind starea mediului în județul Botoșani în anul 2019). -

Ecogeographic, Genetic and Taxonomic Studies of the Genus Lathyrus L

ECOGEOGRAPHIC, GENETIC AND TAXONOMIC STUDIES OF THE GENUS LATHYRUS L. BY ALI ABDULLAH SHEHADEH A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Biosciences College of Life and Environmental Sciences University of Birmingham March 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Lathyrus species are well placed to meet the increasing global demand for food and animal feed, at the time of climate change. Conservation and sustainable use of the genetic resources of Lathyrus is of significant importance to allow the regain of interest in Lathyrus species in world. A comprehensive global database of Lathyrus species originating from the Mediterranean Basin, Caucasus, Central and West Asia Regions is developed using accessions in major genebanks and information from eight herbaria in Europe. This Global Lathyrus database was used to conduct gap analysis to guide future collecting missions and in situ conservation efforts for 37 priority species. The results showed the highest concentration of Lathyrus priority species in the countries of the Fertile Crescent, France, Italy and Greece. -

'A Ffitt Place for Any Gentleman'?

‘A ffitt place for any Gentleman’? GARDENS, GARDENERS AND GARDENING IN ENGLAND AND WALES, c. 1560-1660 by JILL FRANCIS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham July 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to investigate gardens, gardeners and gardening practices in early modern England, from the mid-sixteenth century when the first horticultural manuals appeared in the English language dedicated solely to the ‘Arte’ of gardening, spanning the following century to its establishment as a subject worthy of scientific and intellectual debate by the Royal Society and a leisure pursuit worthy of the genteel. The inherently ephemeral nature of the activity of gardening has resulted thus far in this important aspect of cultural life being often overlooked by historians, but detailed examination of the early gardening manuals together with evidence gleaned from contemporary gentry manuscript collections, maps, plans and drawings has provided rare insight into both the practicalities of gardening during this period as well as into the aspirations of the early modern gardener. -

Pdf of JHOS January 2012

JJoouurrnnaall of the HHAARRDDYY OORRCCHHIIDD SSOOCCIIEETTYY Vol. 9 No. 1 (63) January 2012 JOURNAL of the HARDY ORCHID SOCIETY Vol. 9 No. 1 (63) January 2012 The Hardy Orchid Society Our aim is to promote interest in the study of Native European Orchids and those from similar temperate climates throughout the world. We cover such varied aspects as field study, cultivation and propagation, photography, taxonomy and systematics, and practical conservation. We welcome articles relating to any of these subjects, which will be considered for publication by the editorial committee. Please send your submissions to the Editor, and please structure your text according to the “Advice to Authors” (see website www.hardyorchidsociety.org.uk , January 2004 Journal, Members’ Handbook or contact the Editor). Views expressed in journal arti - cles are those of their author(s) and may not reflect those of HOS. The Hardy Orchid Society Committee President: Prof. Richard Bateman, Jodrell Laboratory, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3DS Chairman: Celia Wright, The Windmill, Vennington, Westbury, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY5 9RG [email protected] Vice-Chairman: David Hughes, Linmoor Cottage, Highwood, Ringwood, Hants., BH24 3LE [email protected] Secretary: Alan Leck, 61 Fraser Close, Deeping St. James, Peterborough, PE6 8QL [email protected] Treasurer: John Wallington, 17, Springbank, Eversley Park Road, London, N21 1JH [email protected] Membership Secretary: Moira Tarrant, Bumbys, Fox Road, Mashbury, -

The 2 Fundamental Questions: Linneaus and Kirchner

2/1/2011 The 2 fundamental questions: y Has evolution taken pp,lace, and if so, what is the Section 4 evidence? Professor Donald McFarlane y If evolution has taken place, what is the mechanism by which it works? Lecture 2 Evolutionary Ideas Evidence for evolution before Darwin Golden Age of Exploration y Magellan’s voyage –1519 y John Ray –University of y Antonius von Leeuwenhoek ‐ microbes –1683 Cambridge (England) y “Catalog of Cambridge Plants” – 1660 –lists 626 species y 1686 –John Ray listing thousands of plant species! y In 1678, Francis Willoughby publishes “Ornithology” Linneaus and Kirchner Athenasius Kircher ~ 1675 –Noah’s ark Carl Linneaus – Sistema Naturae ‐ 1735 Ark too small!! Uses a ‘phenetic” classification – implies a phylogenetic relationship! 300 x 50 x 30 cubits ~ 135 x 20 x 13 m 1 2/1/2011 y Georges Cuvier 1769‐ 1832 y “Fixity of Species” Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 • Enormous diversity of life –WHY ??? JBS Haldane " The Creator, if He exists, has "an inordinate fondness for beetles" ". Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y The discovery of variation. y Comparative Anatomy. Pentadactyl limbs Evidence for Evolution –prior to Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 1830 y Fossils – homologies with living species y Vestigal structures Pentadactyl limbs !! 2 2/1/2011 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y Invariance of the fossil sequence y Plant and animal breeding JBS Haldane: “I will give up my belief in evolution if someone finds a fossil rabbit in the Precambrian.” Charles Darwin Jean Baptiste Lamark y 1744‐1829 y 1809 –1882 y Organisms have the ability to adapt to their y Voyage of Beagle 1831 ‐ 1836 environments over the course of their lives. -

Medical Appropriation in the 'Red' Atlantic: Translating a Mi'kmaq

1 Medical Appropriation in the ‘Red’ Atlantic: Translating a Mi’kmaq smallpox cure in the mid-nineteenth century Farrah Lawrence-Mackey University College London Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History and Philosophy of Science Department of Science and Technology Studies 2018 2 I, Farrah Mary Lawrence-Mackey confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 ABSTRACT This thesis answers the questions of what was travelling, how, and why, when a Kanien’kehaka woman living amongst the Mi’kmaq at Shubenacadie sold a remedy for smallpox to British and Haligonian colonisers in 1861. I trace the movement of the plant (known as: Mqo’oqewi’k, Indian Remedy, Sarracenia purpurea, and Limonio congener) and knowledges of its use from Britain back across the Atlantic. In exploring how this remedy travelled, why at this time and what contexts were included with the plant’s removal I show that rising scientific racism in the nineteenth century did not mean that Indigenous medical flora and knowledge were dismissed wholesale, as scholars like Londa Schiebinger have suggested. Instead conceptions of indigeneity were fluid, often lending authority to appropriated flora and knowledge while the contexts of nineteenth-century Britain, Halifax and Shubenacadie created the Sarracenia purpurea, Indian Remedy and Mqo’oqewi’k as it moved through and between these spaces. Traditional accounts of bio-prospecting argue that as Indigenous flora moved, Indigenous contexts were consistently stripped away. This process of stripping shapes Indigenous origins as essentialised and static. -

Conserving Europe's Threatened Plants

Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation By Suzanne Sharrock and Meirion Jones May 2009 Recommended citation: Sharrock, S. and Jones, M., 2009. Conserving Europe’s threatened plants: Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Richmond, UK ISBN 978-1-905164-30-1 Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK Design: John Morgan, [email protected] Acknowledgements The work of establishing a consolidated list of threatened Photo credits European plants was first initiated by Hugh Synge who developed the original database on which this report is based. All images are credited to BGCI with the exceptions of: We are most grateful to Hugh for providing this database to page 5, Nikos Krigas; page 8. Christophe Libert; page 10, BGCI and advising on further development of the list. The Pawel Kos; page 12 (upper), Nikos Krigas; page 14: James exacting task of inputting data from national Red Lists was Hitchmough; page 16 (lower), Jože Bavcon; page 17 (upper), carried out by Chris Cockel and without his dedicated work, the Nkos Krigas; page 20 (upper), Anca Sarbu; page 21, Nikos list would not have been completed. Thank you for your efforts Krigas; page 22 (upper) Simon Williams; page 22 (lower), RBG Chris. We are grateful to all the members of the European Kew; page 23 (upper), Jo Packet; page 23 (lower), Sandrine Botanic Gardens Consortium and other colleagues from Europe Godefroid; page 24 (upper) Jože Bavcon; page 24 (lower), Frank who provided essential advice, guidance and supplementary Scumacher; page 25 (upper) Michael Burkart; page 25, (lower) information on the species included in the database. -

2017 Magdalen College Record

Magdalen College Record Magdalen College Record 2017 2017 Conference Facilities at Magdalen¢ We are delighted that many members come back to Magdalen for their wedding (exclusive to members), celebration dinner or to hold a conference. We play host to associations and organizations as well as commercial conferences, whilst also accommodating summer schools. The Grove Auditorium seats 160 and has full (HD) projection fa- cilities, and events are supported by our audio-visual technician. We also cater for a similar number in Hall for meals and special banquets. The New Room is available throughout the year for private dining for The cover photograph a minimum of 20, and maximum of 44. was taken by Marcin Sliwa Catherine Hughes or Penny Johnson would be pleased to discuss your requirements, available dates and charges. Please contact the Conference and Accommodation Office at [email protected] Further information is also available at www.magd.ox.ac.uk/conferences For general enquiries on Alumni Events, please contact the Devel- opment Office at [email protected] Magdalen College Record 2017 he Magdalen College Record is published annually, and is circu- Tlated to all members of the College, past and present. If your contact details have changed, please let us know either by writ- ing to the Development Office, Magdalen College, Oxford, OX1 4AU, or by emailing [email protected] General correspondence concerning the Record should be sent to the Editor, Magdalen College Record, Magdalen College, Ox- ford, OX1 4AU, or, preferably, by email to [email protected]. -

Gerard's Herbal the OED Defines the Word

Gerard’s Herbal The OED defines the word ‘herbal’ (n) as: ‘a book containing the names and descriptions of herbs, or of plants in general, with their properties and virtues; a treatise in plants.’ Charles Singer, historian of medicine and science, describes herbals as ‘a collection of descriptions of plants usually put together for medical purposes. The term is perhaps now-a-days used most frequently in connection with the finely illustrated works produced by the “fathers of botany” in the fifteenth and sixteenth century.’1 Although the origin of the herbal dates back to ‘remote antiquity’2 the advent of the printing press meant that herbals could be produced in large quantities (in comparison to their earlier manuscript counterparts) with detailed woodcut and metal engraving illustrations. The first herbal printed in Britain was Richard Banckes' Herball of 15253, which was written in plain text. Following Banckes, herbalists such as William Turner and John Gerard gained popularity with their lavishly illustrated herbals. Gerard’s Herbal was originally published in 1597; it is regarded as being one of the best of the printed herbals and is the first herbal to contain an illustration of a potato4. Gerard did Illustration of Gooseberries from not have an enormously interesting life; he was Gerard’s Herbal (1633), demonstrating the intricate detail that ‘apprenticed to Alexander Mason, a surgeon of 5 characterises this text. the Barber–Surgeons' Company’ and probably ‘travelled in Scandinavia and Russia, as he frequently refers to these places in his writing’6. For all his adult life he lived in a tenement with a garden probably belonging to Lord Burghley. -

Exploring Patterns of Variation Within the Central-European Tephroseris Longifolia Agg.: Karyological and Morphological Study

Preslia 87: 163–194, 2015 163 Exploring patterns of variation within the central-European Tephroseris longifolia agg.: karyological and morphological study Karyologická a morfologická variabilita v rámci Tephroseris longifolia agg. Katarína O l š a v s k á1, Barbora Šingliarová1, Judita K o c h j a r o v á1,3, Zuzana Labdíková2,IvetaŠkodová1, Katarína H e g e d ü š o v á1 &MonikaJanišová1 1Institute of Botany, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Dúbravská cesta 9, SK-84523 Bratislava, Slovakia, e-mail: [email protected]; 2Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Matej Bel, Tajovského 40, SK-97401 Banská Bystrica, Slovakia; 3Comenius University, Bratislava, Botanical Garden – detached unit, SK-03815 Blatnica, Slovakia Olšavská K., Šingliarová B., Kochjarová J., LabdíkováZ.,ŠkodováI.,HegedüšováK.&JanišováM. (2015): Exploring patterns of variation within the central-European Tephroseris longifolia agg.: karyological and morphological study. – Preslia 87: 163–194. Tephroseris longifolia agg. is an intricate complex of perennial outcrossing herbaceous plants. Recently, five subspecies with rather separate distributions and different geographic patterns were assigned to the aggregate: T. longifolia subsp. longifolia, subsp. pseudocrispa and subsp. gaudinii predominate in the Eastern Alps; the distribution of subsp. brachychaeta is confined to the northern and central Apennines and subsp. moravica is endemic in the Western Carpathians. Carpathian taxon T. l. subsp. moravica is known only from nine localities in Slovakia and the Czech Republic and is treated as an endangered taxon of European importance (according to Natura 2000 network). As the taxonomy of this aggregate is not comprehensively elaborated the aim of this study was to detect variability within the Tephroseris longifolia agg. -

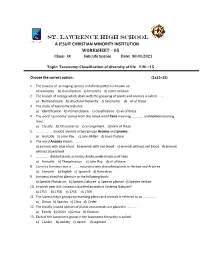

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL a JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION WORKSHEET – 05 Class: IX Sub: Life Science Date: 30.01.2021

ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL A JESUIT CHRISTIAN MINORITY INSTITUTION WORKSHEET – 05 Class: IX Sub: Life Science Date: 30.01.2021 Topic: Taxonomy-Classification of diversity of life F.M. : 15 Choose the correct option: (1x15=15) 1. The process of arranging species in definite pattern is known as: a) taxonomy b) classification c) hierarchy d) nomenclature 2. The branch of biology which deals with the grouping of plants and animals is called …….. a) Nomenclature b) structural hierarchy c) taxonomy d) all of these 3. The study of taxonomy includes: a) Identification b) nomenclature c) classification d) all of these 4. The word ‘taxonomy’ comes from the Greek word Taxis meaning ………….. and nomos meaning laws: a) Classify b) Characterize c) arrangement d)none of these 5. ……………….. divided animals in two groups Anaima and Enaima . a) Aristotle b) John Ray c) John Miller d) Louis Pasteur 6. The word Anaima means …...... a) animals with blue blood b) animals with red blood c) animals without red blood d) animals without blue blood 7. ……………. divided plants as herbs,shrubs,undershrubs and trees. a) Aristotle b) Theophrastus c) John Ray d) all of these 8. Carrolus Linnaeus was a ……… naturalist who classisfied plants in Herbae and Arborea. a) Swedish b) English c) Spainish d) Australian 9. Linnaeus classified plants in in the following book: a) Species Plantarum b) Species Naturae c) Species plantae d) Species herbae 10. In which year did Linnaeus classified animals in Systema Naturae? a) 1753 b) 1758 c) 1756 d) 1769 11. The lowest major group representing plants and animals is referred to as …………… a) Genus b) Species c) Class d) Order 12.