Victorian Science and Spiritualism in the Legend of Hell House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Architecture of Afterlife: Future Cemetery in Metropolis

ARCHITECTURE OF AFTERLIFE: FUTURE CEMETERY IN METROPOLIS A DARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARCHITECTURE MAY 2017 BY SHIYU SONG DArch Committee: Joyce Noe, Chairperson William Chapman Brian Takahashi Key Words: Conventional Cemetery, Contemporary Cemetery, Future Cemetery, High-technology Innovation Architecture of Afterlife: Future Cemetery in Metropolis Shiyu Song April 2017 We certify that we have read this Doctorate Project and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Architecture in the School of Architecture, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Doctorate Project Committee ___________________________________ Joyce Noe ___________________________________ William Chapman ___________________________________ Brian Takahashi Acknowledgments I dedicate this thesis to everyone in my life. I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my committee chair, Professor Joyce Noe, for her support, guidance and insight throughout this doctoral project. Many thanks to my wonderful committee members William Chapman and Brian Takahashi for their precious and valuable guidance and support. Salute to my dear professor Spencer Leineweber who inspires me in spirit and work ethic. Thanks to all the professors for your teaching and encouragement imparted on me throughout my years of study. After all these years of study, finally, I understand why we need to study and how important education is. Overall, this dissertation is an emotional research product. As an idealist, I choose this topic as a lesson for myself to understand life through death. The more I delve into the notion of death, the better I appreciate life itself, and knowing every individual human being is a bless; everyday is a present is my best learning outcome. -

Not Your Usual Halloween Movies

WHEN YOU CRAVE SOMETHING DIFFERENT By Adam Groves, The Bedlam Files 1. MS. 45 (1981) An easy pick, given that I consider Abel Ferrara’s MS. 45 the highlight of the rape-revenge grindhouse movie cycle, and that the film’s climax, involving a massacre at a Halloween party, is MS. 45’s undoubted highlight. 2. THE NIGHT THAT PANICKED AMERICA (1975) This one’s a bit of a cheat (as the night in question is actually October 30) but a worthwhile choice nonetheless, a reality-based horror story that effectively dramatizes Orson Welles’ 1936 WAR OF THE WORLDS radio broadcast and the widespread chaos that resulted. 3. THE AMERICAN SCREAM (2012) A most interesting documentary portrayal of the DIY Halloween haunted house craze, as seen through the attempts of several Massachusetts residents at scaring the Hell out of their neighbors. 4. GINGER SNAPS (2001) The finest werewolf movie of the 00s, and much it takes place on Halloween. 5. HELL HOUSE (2002) Another Halloween haunted house doco, this one focusing on a Christian run attraction designed to scare people straight. A film that’s both hilarious and appalling in equal measure. 6. THE OCTOBER GARDEN (1983) A ten minute short marked by skilled and precise horror filmmaking that, to add to the superlatives, was accomplished entirely without dialogue. 7. RIDING THE BULLET (2004) A puzzlingly underrated Stephen King adaptation that’s scary, thoughtful and even touching in its evocation of Halloween night, 1969, haunted by a very real ghost. 8. TERRIFIER (2011) I’m referring here to the twenty minute TERRIFIER short and not the misguided 2016 feature version, as in short film format the highly minimalistic narrative, consisting of a young woman being chased around by a clown faced manic on Halloween, works quite well. -

Hakuna Matata Newsletter

P A G E 1 S E P T E M B E R 2 0 2 0 HAKUNA MATATA BY THE STUDENTS OF MODERN HIGH SCHOOL, IGCSE WHAT'S INSIDE? DIWALI! DURGA PUJA! HALLOWEEN! P A G E 2 S E P T E M B E R 2 0 2 0 EDIT RIAL Et Lux in Tenebris Lucet - And Light shines in the Darkness Pujo is finally here!!!! The festivities have begun! In the “normal” situation, we would all be cleaning our houses, preparing for Maa to come, buying fireworks, deciding costumes for Halloween and making endless plans for pandal hopping. The current circumstances have changed the usual way of celebration. We were all heartbroken when we found out that we could no longer go out and burst crackers or go trick or treating. We all look forward to this time of year and eagerly await to spend time with our loved ones. However, do not be disheartened. With all the new technology, you can easily keep in touch and virtually enjoy with your family and friends. You could have a Halloween costume party or a good online “adda” session with your best friends! It is the ethos of fun and love that is the most important, especially during this season. The festive times really do bring out the best in people. The amount of love and celebration that is in the air is unparalleled. In these dark hours, this time is just what people need to get their spirits up. So enjoy yourself to the fullest, get into the merry-making spirit, and celebrate these festivities like you do every year. -

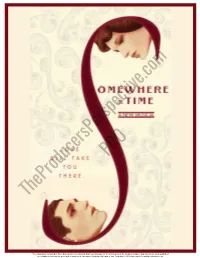

Theproducersperspective.Com

PRO TheProducersPerspective.com www.SomewhereInTime.com 1 The information contained in these documents is confidential, privileged and only for the information of the intended recipient and may not be used, published or redistributed without the prior written consent of Davenport Theatrical Enterprises, Inc. Copyright © 2016 Davenport Theatrical Enterprises, Inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS A Note From Ken Davenport ..........................................................................................3 Synopsis .................................................................................................................................4 Timeline .................................................................................................................................5 Fun Facts About Somewhere in Time .........................................................................6 World Premiere ................................................................................................................. 7 Creative Team ....................................................................................................................8 Production Team ........................................................................................................... 12 Press .................................................................................................................................. 13 The Materials ................................................................................................................. 14 Budget & -

The Cost of Halloween and Spooky Season Is Upon Us, Lars a Year in Ticket Sales

Tuesday, October 15th, 2019 ǀ Volume 138 ǀ Issue 10 ǀ Reaching students, faculty, and staff of the University of North Dakota since 1888 Inside this issue Zodiac Signs 4 Haunted UND 5 For more content Halloween Bash 8 visit www.dakotastudent.com /dakotastudent /DakotaStudent @dakotastudent History of Halloween When and how did this tradition start? Brianna Mayhair Dakota Student Today, Halloween is seen has a fun holiday that allows people to dress up and become some- one else for a night and col- lect as much candy as possible, but how did it start? Around 2,000 years ago when the Celts were in what is present-day Ire- land, the United Kingdom, and northern France, they creat- ed Samhain. The ancient Celt- ic Festival of Samhain, which included people having bon- fires and dressing up to scare off ghosts and other evil spir- its. The spirits were thought to damage crops and cause trou- ble. Samhain is believed to have started Halloween. Around this time period, November 1 was the day that marked the end of summer and the beginning of winter, which was associated with death. They believed that the worlds of the living and the dead collided on the night of October 31, so they created Samhain. Celts believed that the spirits not only caused trouble and damaged crops, but also affected the priests as well. They believed that the spirits made it easier for the priests to predict the future. To please the Celtic deities and prevent Trevor Alveshere/Dakota Student the spread of trouble, the Celts Halloween has an extensive history. -

0X0a I Don't Know Gregor Weichbrodt FROHMANN

0x0a I Don’t Know Gregor Weichbrodt FROHMANN I Don’t Know Gregor Weichbrodt 0x0a Contents I Don’t Know .................................................................4 About This Book .......................................................353 Imprint ........................................................................354 I Don’t Know I’m not well-versed in Literature. Sensibility – what is that? What in God’s name is An Afterword? I haven’t the faintest idea. And concerning Book design, I am fully ignorant. What is ‘A Slipcase’ supposed to mean again, and what the heck is Boriswood? The Canons of page construction – I don’t know what that is. I haven’t got a clue. How am I supposed to make sense of Traditional Chinese bookbinding, and what the hell is an Initial? Containers are a mystery to me. And what about A Post box, and what on earth is The Hollow Nickel Case? An Ammunition box – dunno. Couldn’t tell you. I’m not well-versed in Postal systems. And I don’t know what Bulk mail is or what is supposed to be special about A Catcher pouch. I don’t know what people mean by ‘Bags’. What’s the deal with The Arhuaca mochila, and what is the mystery about A Bin bag? Am I supposed to be familiar with A Carpet bag? How should I know? Cradleboard? Come again? Never heard of it. I have no idea. A Changing bag – never heard of it. I’ve never heard of Carriages. A Dogcart – what does that mean? A Ralli car? Doesn’t ring a bell. I have absolutely no idea. And what the hell is Tandem, and what is the deal with the Mail coach? 4 I don’t know the first thing about Postal system of the United Kingdom. -

American Halloween: Enculturation, Myths and Consumer Culture

American Halloween: Enculturation, Myths and Consumer Culture Shabnam Yousaf Quaid I Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan Abstract The cultish festival of Halloween is encultured through mythology and has become a hybrid consumer culture in the American society. Historiographical evidences illustrate that how it was being Christianized in the 9th century CE and transformed a Pagan Northern-European religious tradition from its adaptation to the enculturation process by the early church, to remember the dead in tricking and treating manners. This paper will illuminate the intricate medieval history of Celtic origins of Halloween, etymology of Samhain festival, rites of passages and the religious rituals practicing in America regarding Halloween that how it evolved from paganism to Neo-paganism and hybridized through materialist glorification from mythology to consumer culture. The mid of 19th century witnessed the arrival of Samhain rituals in America with the displacement of Irish population. Presently, this festival is infused with the folk traditions and carnivals. The trajectory penetrates its roots from discourse to practical implications, incorporated in American culture and became materialized. To assess and analyze the concoction of mythology, enculturation into culturally materialized form and developed into a consumer culture, This paper will take the assistance from Marvin Harris ‘Cultural Materialism’, to seek the behavioral and mental superstructure of the American social fabric for operationalizing the connections and to determine the way forward to explore the rhetorical fabricated glorification of consumer culture inculcated through late-capitalism, will be assessed by Theodore Adorno’s theoretical grounds of ‘The Culture Industry’. This article will re-orientate and enlighten the facts and evolving processes practicing in the American society and inquire that how the centuries old mythologies are being encultured and amalgamated with the socio-cultural, religious and economic interests. -

Inside Killjoy's Kastle Dykey Ghosts, Feminist Monsters, and Other

INSIDE KILLJOY’S KASTLE DYKEY GHOSTS, FEMINIST MONSTERS, AND OTHER LESBIAN HAUNTINGS Edited by Allyson Mitchell and Cait McKinney In collaboration with the Art Gallery of York University Art Gallery of York University • Toronto UBC PRESS © SAMPLE MATERIAL Contents Acknowledgments xi Lesbian Rule: Welcome to the Hell House 3 Cait McKinney and Allyson Mitchell RISING FROM THE DEAD: INCEPTION 1. Scaling Up and Sharing Out Dyke Culture: Killjoy’s Kastle’s Haunted Block Party 22 Heather Love Lesbianizing the Institution: The Haunting Effects of Killjoy Hospitality at the Art Gallery of York University 32 Emelie Chhangur 2. Feminist Killjoys (and Other Wilful Subjects) 38 Sara Ahmed Killjoy in the ONE Archives: Activating Los Angeles’s Queer Art and Activist Histories 54 David Evans Frantz UBC PRESS © SAMPLE MATERIAL THE KASTLE: EXECUTION 3. Inside Job: Learning, Collaboration, and Queer-Feminist Contagion in Killjoy’s Kastle 60 Helena Reckitt Valerie Solanas as the Goddamned Welcoming Committee 80 Felice Shays Valerie Solanas Script 82 4. Playing Demented Women’s Studies Professor Tour Guide, or Performing Monstrosity in Killjoy’s Kastle 85 Moynan King Demented Women’s Studies Professor Tour Guide Script 98 The Sound of White Girls Crying 106 Nazmia Jamal Paranormal Killjoys 108 Ginger Brooks Takahashi Menstruating Trans Man 111 Chase Joynt A Ring around Your Finger Is a Cord around Your Genitals! 113 Chelsey Lichtman Once upon a Time I Was a Riot Ghoul 115 Kalale Dalton-Lutale Riot Ghoul 117 Andie Shabbar viii Contents UBC PRESS © SAMPLE MATERIAL Inconvenienced 119 Madelyne Beckles On the Cusp of the Kastle 121 Karen Tongson 5. -

Seeing All of Life Through the Truth of Scripture

PARENT MEMO Lesson 9 Seeing All of Life Through the Truth of Scripture MAIN IDEAS We have seen that the Bible is the source of truth for all of life’s most important questions. God must act to remove a sinner’s blindness so that he will accept the truth and believe in Jesus. After a person has come to know and love the truth of the Gospel, the Bible should be the “lens” through which he sees and interprets everything else in life. This involves a process in which the mind is renewed and transformed. A Christian must ask the question: How now should I live? Summary from Previous Lessons: SATAN’S LIES + SINFUL HEART à REJECT THE TRUTH à GOD’S WRATH GOD’S TRUTH + NEW HEART à TRUST IN JESUS à ETERNAL LIFE The Truth • The Gospel is meant to transform our lives. (See Romans 12:2 and Colossians 4:6-8.) • The Bible is to be the lens through which we see and interpret everything in life. (See Psalm 43:3a; Psalm 119:105; and 2 Timothy 3:16-17.) The Bible Answers the Most Important Questions 1. How did we get here? 2. Why do we exist? 3. What is wrong with the world? 4. What is the solution? 5. What will happen when we die? 6. How now should we live? ARTICLE Read and discuss the article sent home with your student “Christians and Halloween,” by Travis Allen. How might God’s truth transform the way in which you see, interpret, and respond to a celebration such as Halloween? INTERACTING WITH YOUR STUDENT Your student has been asked to apply one truth learned from this lesson to his/her life this week. -

Disturbia 1 the House Down the Street: the Suburban Gothic In

Notes Introduction: Welcome to Disturbia 1. Siddons, p.212. 2. Clapson, p.2. 3. Beuka, p.23. 4. Clapson, p.14. 5. Chafe, p.111. 6. Ibid., p.120. 7. Patterson, p.331. 8. Rome, p.16. 9. Patterson, pp.336–8. 10. Keats cited in Donaldson, p.7. 11. Keats, p.7. 12. Donaldson, p.122. 13. Donaldson, The Suburban Myth (1969). 14. Cited in Garreau, p.268. 15. Kenneth Jackson, 1985, pp.244–5. 16. Fiedler, p.144. 17. Matheson, Stir of Echoes, p.106. 18. Clapson; Beuka, p.1. 1 The House Down the Street: The Suburban Gothic in Shirley Jackson and Richard Matheson 1. Joshi, p.63. Indeed, King’s 1979 novel Salem’s Lot – in which a European vampire invades small town Maine – vigorously and effectively dramatises this notion, as do many of his subsequent narratives. 2. Garreau, p.267. 3. Skal, p.201. 4. Dziemianowicz. 5. Cover notes, Richard Matheson, I Am Legend, (1954: 1999). 6. Jancovich, p.131. 7. Friedman, p.132. 8. Hereafter referred to as Road. 9. Friedman, p.132. 10. Hall, Joan Wylie, in Murphy, 2005, pp.23–34. 11. Ibid., p.236. 12. Oppenheimer, p.16. 13. Mumford, p.451. 14. Donaldson, p.24. 15. Clapson, p.1. 201 202 Notes 16. Ibid., p.22. 17. Shirley Jackson, The Road Through the Wall, p.5. 18. Friedman, p.79. 19. Shirley Jackson, Road, p.5. 20. Anti-Semitism in a suburban setting also plays a part in Anne Rivers Siddon’s The House Next Door and, possibly, in Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (in which the notably Aryan hero fends off his vampiric next-door neighbour with a copy of the Torah). -

Ape Chronicles #035

For a Man! PLANET OF THE APES 1957 The Three Faces of Eve ARMY ARCHERD WHO IS WHO ? 1957 Peyton Place FILMOGRAPHY 1957 No Down Payment 1958 Teacher's Pet (uncredited) FILMOGRAPHY (AtoZ) 1957 Kiss Them for Me 1963 Under the Yum Yum Tree Compiled by Luiz Saulo Adami 1957 A Hatful of Rain 1964 What a Way to Go! (uncredited) http://www.mcanet.com.br/lostinspace/apes/ 1957 Forty Guns 1966 The Oscar (uncredited) apes.html 1957 The Enemy Below 1968 The Young Runaways (uncredited) [email protected] 1957 An Affair to Remember 1968 Planet of the Apes (uncredited) AUTHOR NOTES 1958 The Roots of Heaven 1968 Wild in the Streets Thanks to Alexandre Negrão Paladini, from 1958 Rally' Round the Flag, Boys! 1970 Beneath the Planet of the Apes Brazil; Terry Hoknes, from Canadá; Jeff 1958 The Young Lions (uncredited) Krueger, from United States of America; 1958 The Long, Hot Summer 1971 Escape from the Planet of the Apes and Philip Madden, from England. 1958 Ten North Frederick 1972 Conquest of the Planet of the Apes 1958 The Fly (uncredited) 1959 Woman Obsessed 1973 Battle for the Planet of the Apes To remind a film, an actor or an actress, a 1959 The Man Who Understood Women (uncredited) musical score, an impact image, it is not so 1959 Journey to the Center of the Earth/Trip 1974 The Outfit difficult for us, spectators of movies or TV. to the Center of the Earth 1976 Won Ton Ton, the Dog Who Saved Really difficult is to remind from where else 1959 The Diary of Anne Frank Hollywood we knew this or that professional. -

The Children's Horror Film

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/90706 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications The Children’s Horror Film: Beneficial fear and subversive pleasure in an (im)possible Hollywood subgenre Catherine Lester A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television Studies Department of Film and Television Studies University of Warwick October 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 4 Declaration of Inclusion of Published Work ............................................................................ 5 Abstract .................................................................................................................................... 6 List of Illustrations .................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction – Thinking of the Children ......................................................................... 11 Structure and Aims ...........................................................................................................