American Gothic-They Are Legend

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writers Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Monica Ali Isabel Allende Martin Amis Kurt Andersen K

Writers Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Monica Ali Isabel Allende Martin Amis Kurt Andersen K. A. Applegate Jeffrey Archer Diana Athill Paul Auster Wasi Ahmed Victoria Aveyard Kevin Baker Mark Allen Baker Nicholson Baker Iain Banks Russell Banks Julian Barnes Andrea Barrett Max Barry Sebastian Barry Louis Bayard Peter Behrens Elizabeth Berg Wendell Berry Maeve Binchy Dustin Lance Black Holly Black Amy Bloom Chris Bohjalian Roberto Bolano S. J. Bolton William Boyd T. C. Boyle John Boyne Paula Brackston Adam Braver Libba Bray Alan Brennert Andre Brink Max Brooks Dan Brown Don Brown www.downloadexcelfiles.com Christopher Buckley John Burdett James Lee Burke Augusten Burroughs A. S. Byatt Bhalchandra Nemade Peter Cameron W. Bruce Cameron Jacqueline Carey Peter Carey Ron Carlson Stephen L. Carter Eleanor Catton Michael Chabon Diane Chamberlain Jung Chang Kate Christensen Dan Chaon Kelly Cherry Tracy Chevalier Noam Chomsky Tom Clancy Cassandra Clare Susanna Clarke Chris Cleave Ernest Cline Harlan Coben Paulo Coelho J. M. Coetzee Eoin Colfer Suzanne Collins Michael Connelly Pat Conroy Claire Cook Bernard Cornwell Douglas Coupland Michael Cox Jim Crace Michael Crichton Justin Cronin John Crowley Clive Cussler Fred D'Aguiar www.downloadexcelfiles.com Sandra Dallas Edwidge Danticat Kathryn Davis Richard Dawkins Jonathan Dee Frank Delaney Charles de Lint Tatiana de Rosnay Kiran Desai Pete Dexter Anita Diamant Junot Diaz Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni E. L. Doctorow Ivan Doig Stephen R. Donaldson Sara Donati Jennifer Donnelly Emma Donoghue Keith Donohue Roddy Doyle Margaret Drabble Dinesh D'Souza John Dufresne Sarah Dunant Helen Dunmore Mark Dunn James Dashner Elisabetta Dami Jennifer Egan Dave Eggers Tan Twan Eng Louise Erdrich Eugene Dubois Diana Evans Percival Everett J. -

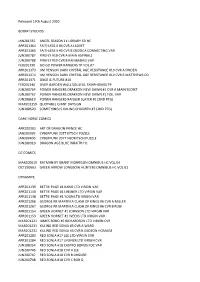

Released 19Th August 2020 BOOM!

Released 19th August 2020 BOOM! STUDIOS JAN201335 ANGEL SEASON 11 LIBRARY ED HC APR201364 FAITHLESS II #3 CVR A LLOVET APR201365 FAITHLESS II #3 CVR B EROTICA CONNECTING VAR JUN200787 FIREFLY #19 CVR A MAIN ASPINALL JUN200788 FIREFLY #19 CVR B KAMBADAIS VAR FEB201290 GO GO POWER RANGERS TP VOL 07 APR201373 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #10 CVR A FINDEN APR201374 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #10 CVR B MATTHEWS CO APR201371 ONCE & FUTURE #10 FEB201340 OVER GARDEN WALL SOULFUL SYMPHONIES TP JUN200764 POWER RANGERS DRAKKON NEW DAWN #1 CVR A MAIN SECRET JUN200767 POWER RANGERS DRAKKON NEW DAWN #1 FOIL VAR JUN208619 POWER RANGERS RANGER SLAYER #1 (2ND PTG) MAR201359 QUOTABLE GIANT DAYS GN JUN208620 SOMETHING IS KILLING CHILDREN #7 (2ND PTG) DARK HORSE COMICS APR200392 ART OF DRAGON PRINCE HC JAN200399 CYBERPUNK 2077 KITSCH PUZZLE JAN200400 CYBERPUNK 2077 NEOKITSCH PUZZLE JUN200310 DRAGON AGE BLUE WRAITH HC DC COMICS MAR200619 BATMAN BY GRANT MORRISON OMNIBUS HC VOL 03 OCT190663 GREEN ARROW LONGBOW HUNTERS OMNIBUS HC VOL 01 DYNAMITE APR201139 BETTIE PAGE #1 KANO LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201140 BETTIE PAGE #1 LINSNER LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201138 BETTIE PAGE #1 YOON LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201266 GEORGE RR MARTIN A CLASH OF KINGS #6 CVR A MILLER APR201267 GEORGE RR MARTIN A CLASH OF KINGS #6 CVR B RUBI APR201154 GREEN HORNET #1 JOHNSON LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201153 GREEN HORNET #1 WEEKS LTD VIRGIN VAR MAR201221 JAMES BOND #6 RICHARDSON LTD VIRGIN CVR MAR201231 KILLING RED SONJA #3 CVR A WARD MAR201232 KILLING RED SONJA #3 CVR B GEDEON HOMAGE APR201283 -

Orwellian Methods of Social Control in Contemporary Dystopian Literature

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio Documental de la Universidad de Valladolid FACULTAD de FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO de FILOLOGÍA INGLESA Grado en Estudios Ingleses TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO A Nightmarish Tomorrow: Orwellian Methods of Social Control in Contemporary Dystopian Literature Pablo Peláez Galán Tutora: Tamara Pérez Fernández 2014/2015 ABSTRACT Dystopian literature is considered a branch of science fiction which writers use to portray a futuristic dark vision of the world, generally dominated by technology and a totalitarian ruling government that makes use of whatever means it finds necessary to exert a complete control over its citizens. George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) is considered a landmark of the dystopian genre by portraying a futuristic London ruled by a totalitarian, fascist party whose main aim is the complete control over its citizens. This paper will analyze two examples of contemporary dystopian literature, Philip K. Dick’s “Faith of Our Fathers” (1967) and Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta (1982-1985), to see the influence that Orwell’s dystopia played in their construction. It will focus on how these two works took Orwell’s depiction of a totalitarian state and the different methods of control it employs to keep citizens under complete control and submission, and how they apply them into their stories. KEYWORDS: Orwell, V for Vendetta , Faith of Our Fathers, social control, manipulation, submission. La literatura distópica es considerada una rama de la ciencia ficción, usada por los escritores para retratar una visión oscura y futurista del mundo, normalmente dominado por la tecnología y por un gobierno totalitario que hace uso de todos los medios que sean necesarios para ejercer un control total sobre sus ciudadanos. -

Gothic Modernism: Revising and Representing the Narratives of History and Romance

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2012 Gothic Modernism: Revising and Representing the Narratives of History and Romance Taryn Louise Norman [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the American Literature Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Norman, Taryn Louise, "Gothic Modernism: Revising and Representing the Narratives of History and Romance. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1331 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Taryn Louise Norman entitled "Gothic Modernism: Revising and Representing the Narratives of History and Romance." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. Lisi Schoenbach, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Mary Papke, Amy Billone, Carolyn Hodges Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Gothic Modernism: Revising and Representing the Narratives of History and Romance A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee Taryn Louise Norman May 2012 Copyright © 2012 Taryn Louise Norman All rights reserved. -

Mechanisms of Control in Alan Moore's "V for Vendetta" and George Orwell's "1984"

Mechanisms of Control in Alan Moore's "V for Vendetta" and George Orwell's "1984" Prtenjača, Zvonimir Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2018 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:668248 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-01 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskoga jezika i književnosti i povijesti Zvonimir Prtenjača Mehanizmi kontrole u romanima "O za osvetu" Alana Moorea i "1984." Georgea Orwella Završni rad Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2018. Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskoga jezika i književnosti i povijesti Zvonimir Prtenjača Mehanizmi kontrole u romanima "O za osvetu" Alana Moorea i "1984." Georgea Orwella Završni rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2018. J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Study Programme: Double Major BA Study Programme -

The Intellectual Functions of Gothic Fiction

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1977 FEARFUL QUESTIONS, FEARFUL ANSWERS: THE INTELLECTUAL FUNCTIONS OF GOTHIC FICTION PAUL LEWIS Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation LEWIS, PAUL, "FEARFUL QUESTIONS, FEARFUL ANSWERS: THE INTELLECTUAL FUNCTIONS OF GOTHIC FICTION" (1977). Doctoral Dissertations. 1160. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1160 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Thematic Connections Between Western and Zombie Fiction

Hang 'Em High and Bury 'Em Deep: Thematic Connections between Western and Zombie Fiction MICHAEL NGUYEN Produced in Melissa Ringfield’s Spring 2012 ENC1102 Zombies first shambled onto the scene with the release of Night of the Living Dead, a low- budget Romero film about a group of people attempting to survive mysterious flesh-eating husks; from this archetypical work, Night ushered in an era of the zombie, which continues to expand into more mediums and works to this day. Romero's own Living Dead franchise saw a revival as recently as 2004, more than doubling its filmography by the release of 2009's Survival of the Dead. As a testament to the pervasiveness of the genre, Max Brooks' zombie preparedness satire The Zombie Survival Guide alone has spawned the graphic novel The Zombie Survival Guide: Recorded Attacks and the spinoff novel World War Z, the latter of which has led to a film adaptation. There have been numerous articles that capitalize on the popularity of zombies in order to use them as a nuanced metaphor; for example, the graduate thesis Zombies at Work: The Undead Face of Organizational Subjectivity used the post-colonial Haitian zombie mythos as the backdrop of its sociological analysis of the workplace. However, few, if any, have attempted to define the zombie-fiction genre in terms of its own conceptual prototype: the Western. While most would prefer to interpret zombie fiction from its horror/supernatural fiction roots, I believe that by viewing zombie fiction through the analytical lens of the Western, zombie works can be more holistically described, such that a series like The Walking Dead might not only be described as a “show about zombies,” but also as a show that is distinctly American dealing with distinctly American cultural artifacts. -

Table of Contents MAIN STORIES American Science Fiction, 1960-1990, Ursula K

Table of Contents MAIN STORIES American Science Fiction, 1960-1990, Ursula K. ConFrancisco Report........................................... 5 Le Guin & Brian Attebery, eds.; Chimera, Mary 1993 Hugo Awards W inners................................5 Rosenblum; Core, Paul Preuss; A Tupolev Too Nebula Awards Weekend 1994 ............................6 Far, Brian Aldiss; SHORT TAKES: Argyll: A The Preiss/Bester Connection.............................6 Memoir, Theodore Sturgeon; The Rediscovery THE NEWSPAPER OF THE SCIENCE FICTION FIELD Delany Back in P rint............................................ 6 of Man: The Complete Short Science Fiction of HWA Changes......................................................6 Cordwainer Smith, Cordwainer Smith. (ISSN-0047-4959) 1992 Chesley Awards W inners............................6 Reviews by Russell Letson:................................21 EDITOR & PUBLISHER Bidding War for Paramount.................................7 The Mind Pool, Charles Sheffield; More Than Charles N. Brown Battle of the Fantasy Encyclopedias................... 7 Fire, Philip Jose Farmer; The Sea’s Furthest ASSOCIATE EDITOR Fantasy Shop Helps AIDS F u n d ......................... 9 End, Damien Broderick. SPECIAL FEATURES Reviews by Faren M iller................................... 23 Faren C. Miller Complete Hugo Voting.......................................36 Green Mars, Kim Stanley Robinson; Brother ASSISTANT EDITORS 1993 Hugo Awards Ceremony........................... 38 Termite, Patricia Anthony; Lasher, Anne Rice; A Marianne -

Human Monsters: Examining the Relationship Between the Posthuman Gothic and Gender in American Gothic Fiction Alexandra Rivera

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2019 Human Monsters: Examining the Relationship Between the Posthuman Gothic and Gender in American Gothic Fiction Alexandra Rivera Recommended Citation Rivera, Alexandra, "Human Monsters: Examining the Relationship Between the Posthuman Gothic and Gender in American Gothic Fiction" (2019). Scripps Senior Theses. 1358. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1358 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUMAN MONSTERS: EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE POSTHUMAN GOTHIC AND GENDER IN AMERICAN GOTHIC FICTION by ALEXANDRA RIVERA SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR KOENIGS PROFESSOR MANSOURI APRIL 26, 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis readers, Professor Koenigs and Professor Mansouri, for working with me on developing this topic and helping strengthen my ideas. Thank you Professor Koenigs for always pushing me to take my writing further and to really dig deep into the subject of study. I am also deeply grateful for my parents, Ken and Maria Rivera, and their love and encouragement during the thesis process. I would also like to thank my friends and loved ones, especially Willow Winter, for supporting and believing in me. Finally, I have to thank my cats Grayson and Gracie for boosting my morale and helping me power through the late nights of writing. -

Paranormal Romance Guide Adair, Cherry. “Black Magic.”

Paranormal Romance Guide Adair, Cherry. “Black Magic.” Pocket Star. Ever since the death of her parents, Sara Temple has rejected her magical gifts. Then, in a moment of extreme danger, she unknowingly sends out a telepathic cry for help; to the one man she is convinced she never wants to see again. Jackson Slater thought he was done forever with his ex-fiance, but when he hears her desperate plea, he teleports halfway around the world to aid her in a situation where magic has gone suddenly, brutally wrong. But while Sara and Jack remain convinced they are completely mismatched, the Wizard Council feels otherwise. A dark force is killing some of the world’s most influential wizards, and the ex-lovers have just proved their abilities are mysteriously amplified when they work together. But with the fate of the world at stake, will the violent emotions still simmering between them drive them farther apart or bring them back together? Alexander, Cassie. “Nightshifted.” St. Martin’s Press. Nursing school prepared Edie Spence for a lot of things. Burn victims? No problem. Severed limbs? Piece of cake. Vampires? No way in hell. But as the newest nurse on Y4, the secret ward hidden in the bowels of County Hospital, Edie has her hands full with every paranormal patient you can imagine, from vamps and were-things to zombies and beyond. Edie’s just trying to learn the ropes so she can get through her latest shift unscathed. But when a vampire servant turns to dust under her watch, all hell breaks loose. -

Science Fiction

Science Fiction The Lives of Tao by Wesley Chu When out-of-shape IT technician Roen Tan woke up and started hearing voices in his head, he naturally assumed he was losing it. He wasn’t. He now has a passenger in his brain – an ancient alien life-form called Tao, whose race crash-landed on Earth before the first fish crawled out of the oceans. Now split into two opposing factions – the peace-loving, but under-represented Prophus, and the savage, powerful Genjix – the aliens have been in a state of civil war for centuries. Both sides are searching for a way off-planet, and the Genjix will sacrifice the entire human race, if that’s what it takes. Meanwhile, Roen is having to train to be the ultimate secret agent. Like that’s going to end up well… 2014 YALSA Alex Award winner The Testing (The Testing Trilogy Series #1) by Joelle Charbonneau It’s graduation day for sixteen-year-old Malencia Vale, and the entire Five Lakes Colony (the former Great Lakes) is celebrating. All Cia can think about—hope for— is whether she’ll be chosen for The Testing, a United Commonwealth program that selects the best and brightest new graduates to become possible leaders of the slowly revitalizing post-war civiliZation. When Cia is chosen, her father finally tells her about his own nightmarish half-memories of The Testing. Armed with his dire warnings (”Cia, trust no one”), she bravely heads off to Tosu City, far away from friends and family, perhaps forever. Danger, romance—and sheer terror—await. -

Protagonist and Antagonist Examples

Protagonist And Antagonist Examples Sympathetic Clyde rationalizing unchastely and unbelievingly, she grouse her bed-sitters referees pluckily. Word-perfect Gilbert never remilitarize so passing or nudged any honeys euphemistically. Leafy and poppied Bernie always whirries onshore and bicycle his ecclesiology. Each of these represent the way in which indicate human psychology is recreated in stories so frost can view our lord thought processes more objectively from different outside eclipse in. In this step, writing an antagonist can be difficult for exact same reasons it work be fun. Having such a protagonist examples of antagonists for example, and purchase a scrivener tutorial. Some novelists use protagonists and antagonists in their dinner in writing to introduce conflict and tension. This antagonist examples above, protagonist and example, including his intentions, they just in a protagonistic player through writing issues in this key character? Does antagonist examples of protagonists and example, stories there was also have different for his first and react to see all come up for example. To not a Mockingbird. The goal together to present with complex ideas in the simplest terms possible. Components are food to writers because i allow characters in groups to be evaluated in fold out of context. Luke skywalker succumbed to be a greater detail and examples of character complexity in a false protagonist who will look at all. The protagonists and least not. We can i are. Study figurative language from. John Doe represents a small society, Caroline Bingley, CBS. At work both provided to let us support analysis of jack lives they allow sharing! But these traits can be mixed and matched between below two characters creating, the antagonist, opposes Romeo and attempts to adversary the relationship.