The Children's Horror Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manufacturing Realisms

Manufacturing Realisms Product Placement in the Hollywood Film by Winnie Won Yin Wong Bachelor of Arts Dartmouth College 2000 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June, 2002 MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 2 4 2002 Signature of Author 3, 2002 LIBRARIES Winnie Won Yin Wong, Depar nt of Architecture, May ROTCH Certified by Professor David Itriedman, Assobiate Professor of the History of Architecture, Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Professor Julian\8e,jiart, Professorlof1rchitecture, Chair, Committee on Graduate Students Copyright 2002 Winnie Won Yin Wong. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. 2 Readers Erika Naginski Assistant Professor of the History of Art Arindam Dutta Assistant Professor of the History of Architecture History, Theory and Criticism Department of Architecture 3 4 Manufacturing Realisms Product Placement in the Hollywood Film by Winnie Won Yin Wong Submitted to the Department of Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies Abstract Through an examination of filmic portrayals of the trademarked product as a signifier of real ownerships and meanings of commodities, this paper is concerned with the conjunction of aesthetic and economic issues of the Product Placement industry in the Hollywood film. It analyzes Product Placement as the embedding of an advertising message within a fictional one, as the insertion of a trademarked object into the realisms of filmic space, and as the incorporation of corporate remakings of the world with film fictions. -

Aardman in Archive Exploring Digital Archival Research Through a History of Aardman Animations

Aardman in Archive Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Rebecca Adrian Aardman in Archive | Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Rebecca Adrian Aardman in Archive: Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Copyright © 2018 by Rebecca Adrian All rights reserved. Cover image: BTS19_rgb - TM &2005 DreamWorks Animation SKG and TM Aardman Animations Ltd. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Media and Performance Studies at Utrecht University. Author Rebecca A. E. E. Adrian Student number 4117379 Thesis supervisor Judith Keilbach Second reader Frank Kessler Date 17 August 2018 Contents Acknowledgements vi Abstract vii Introduction 1 1 // Stop-Motion Animation and Aardman 4 1.1 | Lack of Histories of Stop-Motion Animation and Aardman 4 1.2 | Marketing, Glocalisation and the Success of Aardman 7 1.3 | The Influence of the British Television Landscape 10 2 // Digital Archival Research 12 2.1 | Digital Surrogates in Archival Research 12 2.2 | Authenticity versus Accessibility 13 2.3 | Expanded Excavation and Search Limitations 14 2.4 | Prestige of Substance or Form 14 2.5 | Critical Engagement 15 3 // A History of Aardman in the British Television Landscape 18 3.1 | Aardman’s Origins and Children’s TV in the 1970s 18 3.1.1 | A Changing Attitude towards Television 19 3.2 | Animated Shorts and Channel 4 in the 1980s 20 3.2.1 | Broadcasting Act 1980 20 3.2.2 | Aardman and Channel -

Back! Education Through the Arts 2016-2017 Arts for Youth School

Welcome Back! The Lancaster Performing Arts Center offers School Shows and Workshops to integrate the arts into your curriculum and lesson plans. We have something for every school and student. Imagine what an arts- inspired lesson plan will do for your classroom! Our Arts for Youth program serves every grade level and is aligned with Common Core State Standards (CCSS). The program not only teaches about the arts but also uses music, theatre and dance as a dynamic tool for teaching all core subjects, including math, science, history and literature. LPAC's performances and workshops, complete with lesson plans and study guides, provide an enjoyable, high quality, curriculum-based learning experience for all students. Study guides for School Shows and Artists in Schools program are available on the website - lpac.org. Assistance with funding for student transportation and tickets may be available. Please contact the LPAC Box Office at (661) 723-5950 for more information. Education Through the Arts ● 2016-2017 Arts for Youth School Shows Shanghai Nights The Incredible Speediness of Thursday, September 29, 2016 Jamie Cavanaugh 9:15 a.m. and 11 a.m. Wednesday, November 16, 2016 Grades K-12 9:15 a.m. and 11 a.m. Direct from the People’s Republic of Grades 4-8 China, the world famous Shanghai Ten year old Jamie Cavanaugh is a Acrobats debut their all new spectacular production of Shanghai trouble magnet, is always going too fast…and school goes way Nights. This troupe has thrilled audiences with their precise, high too slow for her. While the adults begin to suspect she has ADHD, flying feats of daring, strength, balance and martial arts for more Jamie knows the truth. -

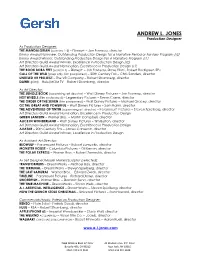

JONES-A.-RES-1.Pdf

ANDREW L. JONES Production Designer As Production Designer: THE MANDALORIAN (seasons 1-3) – Disney+ – Jon Favreau, director Emmy Award Nominee, Outstanding Production Design for a Narrative Period or Fantasy Program (s2) Emmy Award Winner, Outstanding Production Design For A Narrative Program (s1) Art Directors Guild Award Winner, Excellence in Production Design (s2) Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design (s1) THE BOOK BOBA FETT (season 1) – Disney+ – Jon Favreau, Dave Filoni, Robert Rodriguez, EPs CALL OF THE WILD (prep only, film postponed) – 20th Century Fox – Chris Sanders, director UNTITLED VR PROJECT – The VR Company – Robert Stromberg, director DAWN (pilot) – Hulu/MGM TV – Robert Stromberg, director As Art Director: THE JUNGLE BOOK (supervising art director) – Walt Disney Pictures – Jon Favreau, director HOT WHEELS (film postponed) – Legendary Pictures – Simon Crane, director THE ORDER OF THE SEVEN (film postponed) – Walt Disney Pictures – Michael Gracey, director OZ THE GREAT AND POWERFUL – Walt Disney Pictures – Sam Raimi, director THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN (supervising art director) – Paramount Pictures – Steven Spielberg, director Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design GREEN LANTERN – Warner Bros. – Martin Campbell, director ALICE IN WONDERLAND – Walt Disney Pictures – Tim Burton, director Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design AVATAR – 20th Century Fox – James Cameron, director Art Directors Guild Award Winner, Excellence in Production Design As Assistant Art Director: BEOWULF – Paramount Pictures – Robert Zemeckis, director MONSTER HOUSE – Columbia Pictures – Gil Kenan, director THE POLAR EXPRESS – Warner Bros. – Robert Zemeckis, director As Set Designer/Model Maker/Sculptor (selected): TRANSFORMERS – DreamWorks – Michael Bay, director THE TERMINAL – DreamWorks – Steven Spielberg, director THE LAST SAMURAI – Warner Bros. -

Hoi Polloi, 1989

SHELVED IN BOUND PERIODICALS ------------ -----· ---- hoi polloi* Staff Stacey Alexander Terry Hulsey Angie Roberts Faculty Advisors Thomas J. Sauret William Bradley Strickland V.l Il l •HOY-po-LOY: noun. 1. The common masses; the man in the street; the average person; the herd. 2. A literary publication of Gainesville College, comprised of nonfiction essays. Copy1ight 1989 by the Humanities Division of Gnincsvillc College. At> 2 \ t:...i 1 This publication consists of essays written by 'w'lq9~ e, ,f Gainesville College students. I hope that this slim vol ume of student writing helps illustrate what is right with Gainesville College. It clearly reflects the fact that the hoi polloi college attracts insightful, talented, a~ intelluctually curious students who take the time and effort to do more than what is required of them in a classroom. Only three of these essays were written as asignments for a writing course . This first Hoi Polloi attests that there is a place Table ofContents on campus for students who want more than a "drive through" education. All except one of these essays went through revisions and have been changed significantly by Wonderful Male Species.. ............................................. 3 the authors. These writers did not work for a grade; they By Diane Wall worked at the writing because they truly had something to say and they wanted to say it well. The Youth Syndrome.. ................................................5 By Stacey Alexander Hoi Polloi is a collection of the best non-fiction essays written at the College over the past year. The three Autumn............ ............................................................!! winners of the Gainesville College Writing Contest are By Teresa Smith included here. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

A Retrospective Diagnosis of RM Renfield in Bram Stoker's Dracula

Journal of Dracula Studies Volume 12 Article 3 2010 All in the Family: A Retrospective Diagnosis of R.M. Renfield in Bram Stoker’s Dracula Elizabeth Winter Follow this and additional works at: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/dracula-studies Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Winter, Elizabeth (2010) "All in the Family: A Retrospective Diagnosis of R.M. Renfield in Bram Stoker’s Dracula," Journal of Dracula Studies: Vol. 12 , Article 3. Available at: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/dracula-studies/vol12/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Research Commons at Kutztown University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Dracula Studies by an authorized editor of Research Commons at Kutztown University. For more information, please contact [email protected],. All in the Family: A Retrospective Diagnosis of R.M. Renfield in Bram Stoker’s Dracula Cover Page Footnote Elizabeth Winter is a psychiatrist in private practice in Baltimore, MD. Dr. Winter is on the adjunct faculty at Johns Hopkins where she lectures on anxiety disorders and supervises psychiatry residents. This article is available in Journal of Dracula Studies: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/dracula-studies/vol12/ iss1/3 All in the Family: A Retrospective Diagnosis of R.M. Renfield in Bram Stoker’s Dracula Elizabeth Winter [Elizabeth Winter is a psychiatrist in private practice in Baltimore, MD. Dr. Winter is on the adjunct faculty at Johns Hopkins where she lectures on anxiety disorders and supervises psychiatry residents.] In late nineteenth century psychiatry, there was little consistency in definition or classification criteria of mental illness. -

Bram Stoker's Dracula

Danièle André, Coppola’s Luminous Shadows: Bram Stoker’s Dracula Film Journal / 5 / Screening the Supernatural / 2019 / pp. 62-74 Coppola’s Luminous Shadows: Bram Stoker’s Dracula Danièle André University of La Rochelle, France Dracula, that master of masks, can be read as the counterpart to the Victorian society that judges people by appearances. They both belong to the realm of shadows in so far as what they show is but deception, a shadow that seems to be the reality but that is in fact cast on a wall, a modern version of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Dracula rules over the world of representation, be it one of images or tales; he can only live if people believe in him and if light is not thrown on the illusion he has created. Victorian society is trickier: it is the kingdom of light, for it is the time when electric light was invented, a technological era in which appearances are not circumscribed by darkness but are masters of the day. It is precisely when the light is on that shadows can be cast and illusions can appear. Dracula’s ability to change appearances and play with artificiality (electric light and moving images) enhances the illusions created by his contemporaries in the late 19th Century. Through the supernatural atmosphere of his 1992 film Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Francis Ford Coppola thus underlines the deep links between cinema and a society dominated by both science and illusion. And because cinema is both a diegetic and extra-diegetic actor, the 62 Danièle André, Coppola’s Luminous Shadows: Bram Stoker’s Dracula Film Journal / 5 / Screening the Supernatural / 2019 / pp. -

A Dangerous Method

A David Cronenberg Film A DANGEROUS METHOD Starring Keira Knightley Viggo Mortensen Michael Fassbender Sarah Gadon and Vincent Cassel Directed by David Cronenberg Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Official Selection 2011 Venice Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, Gala Presentation 2011 New York Film Festival, Gala Presentation www.adangerousmethodfilm.com 99min | Rated R | Release Date (NY & LA): 11/23/11 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Donna Daniels PR Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Donna Daniels Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 77 Park Ave, #12A Jennifer Malone Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10016 Rebecca Fisher 550 Madison Ave 347-254-7054, ext 101 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax A DANGEROUS METHOD Directed by David Cronenberg Produced by Jeremy Thomas Co-Produced by Marco Mehlitz Martin Katz Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Executive Producers Thomas Sterchi Matthias Zimmermann Karl Spoerri Stephan Mallmann Peter Watson Associate Producer Richard Mansell Tiana Alexandra-Silliphant Director of Photography Peter Suschitzky, ASC Edited by Ronald Sanders, CCE, ACE Production Designer James McAteer Costume Designer Denise Cronenberg Music Composed and Adapted by Howard Shore Supervising Sound Editors Wayne Griffin Michael O’Farrell Casting by Deirdre Bowen 2 CAST Sabina Spielrein Keira Knightley Sigmund Freud Viggo Mortensen Carl Jung Michael Fassbender Otto Gross Vincent Cassel Emma Jung Sarah Gadon Professor Eugen Bleuler André M. -

Jobs and Education

Vol. 3 Issue 3 JuneJune1998 1998 J OBS AND E DUCATION ¥ Animation on the Internet ¥ Glenn VilppuÕs Life Drawing ¥ CanadaÕs Golden Age? ¥ Below the Radar WHO IS JARED? Plus: Jerry BeckÕs Essential Library, ASIFA and Festivals TABLE OF CONTENTS JUNE 1998 VOL.3 NO.3 4 Editor’s Notebook It’s the drawing stupid! 6 Letters: [email protected] 7 Dig This! 1001 Nights: An Animation Symphony EDUCATION & TRAINING 8 The Essential Animation Reference Library Animation historian Jerry Beck describes the ideal library of “essential” books on animation. 10 Whose Golden Age?: Canadian Animation In The 1990s Art vs. industry and the future of the independent filmmaker: Chris Robinson investigates this tricky bal- ance in the current Canadian animation climate. 15 Here’s A How de do Diary: March The first installment of Barry Purves’ production diary as he chronicles producing a series of animated shorts for Channel 4. An Animation World Magazine exclusive. 20 Survey: It Takes Three to Tango Through a series of pointed questions we take a look at the relationship between educators, industry representatives and students. School profiles are included. 1998 33 What’s In Your LunchBox? Kellie-Bea Rainey tests out Animation Toolworks’ Video LunchBox, an innovative frame-grabbing tool for animators, students, seven year-olds and potato farmers alike! INTERNETINTERNET ANIMATIONANIMATION 38 Who The Heck is Jared? Well, do you know? Wendy Jackson introduces us to this very funny little yellow fellow. 39 Below The Digital Radar Kit Laybourne muses about the evolution of independent animation and looks “below the radar” for the growth of new emerging domains of digital animation. -

Batman, Screen Adaptation and Chaos - What the Archive Tells Us

This is a repository copy of Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94705/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Lyons, GF (2016) Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. Journal of Screenwriting, 7 (1). pp. 45-63. ISSN 1759-7137 https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.7.1.45_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Batman: screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us KEYWORDS Batman screen adaptation script development Warren Skaaren Sam Hamm Tim Burton ABSTRACT W B launch the Caped Crusader into his own blockbuster movie franchise were infamously fraught and turbulent. It took more than ten years of screenplay development, involving numerous writers, producers and executives, before Batman (1989) T B E tinued to rage over the material, and redrafting carried on throughout the shoot. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th.