The Dracula Film Adaptations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Is One of the Only Scary Stories That Actually Scared Me

"This is one of the only scary stories that actually scared me. This is quite a long book, so I decided to make it in 5 parts. The next 15 questions will come out soon! Test your memory and see how much you remember." 1. Chapter 1: Jonathan Harker's Journal-Where is Mr. Harker travelling to in the beginning of the novel? Budapest Borgo Pass Bucharest Bistritz 2. True or false: When Harker arrived at the lodge, he received a note from Count Dracula himself. True False 3. The horses were driven by "a tall man with a long brown beard." At first what was the only part of his face that Harker could see? his teeth his nose his ears his eyes 4. We now arrive at Dracula's castle. The door is answered by "a tall old man, clean shaven save for a long white moustache, and clad in black from head to foot, without a single speck of colour about him anywhere." What was it about this man that reminded Harker of the carriage driver? his ears his eyes his grip his teeth 5. A couple of nights later, Harker can't sleep much, so he decides to shave. He is startled by Count Dracula due to the fact that he could not see his reflection in the mirror. At the time he was startled, he cut his chin with the razor. How did Dracula react when he saw the blood? He did nothing He tried to hypnotize him He made a grab for his throat He moved slowly toward him 6. -

Copyrighted Material

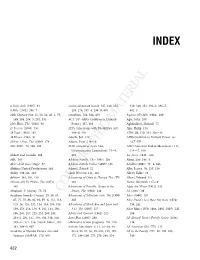

9781405170550_6_ind.qxd 16/10/2008 17:02 Page 432 INDEX 4 Little Girls (1997) 93 action-adventure movie 147, 149, 254, 339, 348, 352, 392–3, 396–7, 8 Mile (2002) 396–7 259, 276, 287–8, 298–9, 410 402–3 20th Century-Fox 21, 30, 34, 40–2, 73, actualities 106, 364, 410 Against All Odds (1984) 289 149, 184, 204–5, 281, 335 ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Agar, John 268 25th Hour, The (2002) 98 Power) 337, 410 Aghdashloo, Shohreh 75 27 Dresses (2008) 353 ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) Ahn, Philip 130 28 Days (2000) 293 398–9, 410 AIDS 99, 329, 334, 336–40 48 Hours (1982) 91 Adachi, Jeff 139 AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power see 100-to-1 Shot, The (1906) 174 Adams, Evan 118–19 ACT-UP 300 (2007) 74, 298, 300 ADC (American-Arab Anti- AIM (American Indian Movement) 111, Discrimination Committee) 73–4, 116–17, 410 Abbott and Costello 268 410 Air Force (1943) 268 ABC 340 Addams Family, The (1991) 156 Akins, Zoe 388–9 Abie’s Irish Rose (stage) 57 Addams Family Values (1993) 156 Aladdin (1992) 73–4, 246 Abilities United Productions 384 Adiarte, Patrick 72 Alba, Jessica 76, 155, 159 ability 359–84, 410 adult Western 111, 410 Albert, Eddie 72 ableism 361, 381, 410 Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet, The (TV) Albert, Edward 375 Abominable Dr Phibes, The (1971) 284 Alexie, Sherman 117–18 365 Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Algie, the Miner (1912) 312 Abraham, F. Murray 75, 76 COPYRIGHTEDDesert, The (1994) 348 MATERIALAli (2001) 96 Academy Awards (Oscars) 29, 58, 63, Adventures of Sebastian Cole, The (1998) Alice (1990) 130 67, 72, 75, 83, 92, 93, -

Sexuality, Blood, Imperialism and the Mytho-Celtic Origins of Dracula

Droch Fhola: Sexuality, Blood, Imperialism and the Mytho-Celtic Origins of Dracula Author: Joseph A Mendes Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/399 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2005 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. 1 Introduction: Dracula. Drac-ula . It is hard to ignore the menace in the name, the morbid delight one gets in pronouncing a name that is riddled with such meaning. At some level, human society is fascinated with the notion of a vampire: a revenant that ret urns from beyond the grave to extract the blood of the living in order to extend its unholy life. It plays on our basic fears as humans, the fear of the dead, the fear of dying, the fear of the unknown, and a fascination with this substance consisting of p lasma, platelets, and cells that runs through our veins. Bram Stoker took all of these fears to new heights when he wrote Dracula , one of the most enduring horror stories to ever be composed. The novel has generated enormous criticism that has chiefly been divided into the camps of Irishness, colonialism/imperialism, and sexuality. Whether it was intentional or not, Stoker’s novel is a breeding ground for almost every sexual fetish, deviance, and perversion that is known to mankind. Characters in the novel engage in mutilation, blood-drinking, perverted fellation, sexual acts in front of their spouse, female domination, male domination, group rape, homosexuality, male penetration, and sadomasochism. -

The Story a Ballet by David Nixon

The Story ACT I Jonathan Harker, a young lawyer, travels to Transylvania to conclude some business with the mysterious old nobleman, Count Dracula. A ballet by David Nixon OBE One night at the Count’s castle, three female Duration: approx. 115min + 20min interval vampires – the Brides of Dracula – try to seduce Harker. Angry, Dracula intervenes, feasts on Harker himself and is transformed into a younger man. Sponsored by Dracula Javier Torres Old Dracula Riku Ito Dracula travels to England, where Harker’s fiancée, Mina Murray Abigail Prudames Mina, is awaiting her beloved’s return. Meanwhile Lucy Westenra Antoinette Brooks-Daw Mina’s friend Lucy is choosing between two potential Taking Northern Ballet Jonathan Harker Lorenzo Trossello suitors, finally accepting the dashing Arthur Holmwood from stage to screen Dr Jack Seward Joseph Taylor over the morose Dr Seward. Arthur Holmwood Matthew Koon Renfield Kevin Poeung Dracula visits Dr Seward’s mental patient, Renfield, Dr Abraham Van Helsing Ashley Dixon and recruits him to do his bidding. He then lures Brides of Dracula Rachael Gillespie Lucy to a cemetery and bites her before feeding Sarah Chun her his own blood. The next day, Mina is concerned by Lucy’s odd behavior, but when Minju Kang she tries to help, she meets Dracula and the two are immediately drawn to each other. Tortured by the grasp Mina has on him, Dracula enacts his revenge on Lucy. Holmwood, Choreography, David Nixon OBE Seward and his mentor Van Helsing try to rescue her but are too late. Direction, Scenario & Costume Design 20 minute intermission, including a ‘behind the scenes’ featurette Set Design Ali Allen ACT II While everyone is mourning the loss of Lucy at her funeral, Mina can’t escape her Lighting Design Tim Mitchell thoughts of Dracula. -

Co-Produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia the Vision

Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia the vision. the voice. From LA to London and Martinique to Mali. We bring you the world ofBlack film. Ifyou're concerned about Black images in commercial film and tele vision, you already know that Hollywood does not reflect the multi- cultural nature 'ofcontemporary society. You know thatwhen Blacks are not absent they are confined to predictable, one-dimensional roles. You may argue that movies and television shape our reality or that they simply reflect that reality. In any case, no one can deny the need to take a closer look atwhat is COIning out of this powerful medium. Black Film Review is the forum you've been looking for. Four times a year, we bringyou film criticiSIn froIn a Black perspective. We look behind the surface and challenge ordinary assurnptiorls about the Black image. We feature actors all.d actresses th t go agaul.st the graill., all.d we fill you Ul. Oll. the rich history ofBlacks Ul. Arnericall. filrnrnakul.g - a history thatgoes back to 19101 And, Black Film Review is the only magazine that bringsyou news, reviews and in-deptll interviews frOtn tlle tnost vibrant tnovetnent in contelllporary film. You know about Spike Lee butwIlat about EuzIlan Palcy or lsaacJulien? Souletnayne Cisse or CIl.arles Burnette? Tllrougll out tIle African cliaspora, Black fi1rnInakers are giving us alternatives to tlle static itnages tIlat are proeluceel in Hollywood anel giving birtll to a wIlole new cinetna...be tIlere! Interview:- ----------- --- - - - - - - 4 VDL.G NO.2 by Pat Aufderheide Malian filmmaker Cheikh Oumar Sissoko discusses his latest film, Finzan, aself conscious experiment in storytelling 2 2 E e Street, NW as ing on, DC 20006 MO· BETTER BLUES 2 2 466-2753 The Music 6 o by Eugene Holley, Jr. -

SLAV-T230 Vampire F2019 Syllabus-Holdeman-Final

The Vampire in European and American Culture Dr. Jeff Holdeman SLAV-T230 11498 (SLAV) (please call me Jeff) SLAV-T230 11893 (HHC section) GISB East 4041 Fall 2019 812-855-5891 (office) TR 4:00–5:15 pm Office hours: Classroom: GA 0009 * Tues. and Thur. 2:45–3:45 pm in GISB 4041 carries CASE A&H, GCC; GenEd A&H, WC * and by appointment (just ask!!!) * e-mail me beforehand to reserve a time * It is always best to schedule an appointment. [email protected] [my preferred method] 812-335-9868 (home) This syllabus is available in alternative formats upon request. Overview The vampire is one of the most popular and enduring images in the world, giving rise to hundreds of monster movies around the globe every year, not to mention novels, short stories, plays, TV shows, and commercial merchandise. Yet the Western vampire image that we know from the film, television, and literature of today is very different from its eastern European progenitor. Nina Auerbach has said that "every age creates the vampire that it needs." In this course we will explore the eastern European origins of the vampire, similar entities in other cultures that predate them, and how the vampire in its look, nature, vulnerabilities, and threat has changed over the centuries. This approach will provide us with the means to learn about the geography, village and urban cultures, traditional social structure, and religions of eastern Europe; the nature and manifestations of Evil and the concept of Limited Good; physical, temporal, and societal boundaries and ritual passage that accompany them; and major historical and intellectual periods (the settlement of Europe, the Age of Reason, Romanticism, Neo-classicism, the Enlightenment, the Victorian era, up to today). -

Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960S and Early 1970S

TV/Series 12 | 2017 Littérature et séries télévisées/Literature and TV series Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.2200 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Dennis Tredy, « Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s », TV/Series [Online], 12 | 2017, Online since 20 September 2017, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 ; DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.2200 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series o... 1 Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy 1 In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, in a somewhat failed attempt to wrestle some high ratings away from the network leader CBS, ABC would produce a spate of supernatural sitcoms, soap operas and investigative dramas, adapting and borrowing heavily from major works of Gothic literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The trend began in 1964, when ABC produced the sitcom The Addams Family (1964-66), based on works of cartoonist Charles Addams, and CBS countered with its own The Munsters (CBS, 1964-66) –both satirical inversions of the American ideal sitcom family in which various monsters and freaks from Gothic literature and classic horror films form a family of misfits that somehow thrive in middle-class, suburban America. -

Adaptation for Audio Production

Adaptation for Audio Production This free download is provided on the understanding and agreement that the script is for personal use only and may not be copied, distributed and / or performed unless written permission is granted by Evcol Entertainment. All rights reserved by the author. DRACULA • based on the novel by Bram Stoker • This adaptation © Simon James Collier 2018 – Evcol Entertainment 1 Based on the novel by Bram Stoker Written, Directed & Produced by Simon James Collier Assistant Director: Helen Elliott Original Music & Sound Design: Zachary Elliott-Hatton Co-Producer: Adam Dechanel Graphic Design: Clockwork Digital Studios Recorded at The Umbrella Rooms Studio, London Engineer: Ben Robbins AUDIO MINI-SERIES – 12 X 20 MINUTE EPISODES DRACULA • based on the novel by Bram Stoker • This adaptation © Simon James Collier 2018 – Evcol Entertainment 2 ‘Dracula’ -- CHARACTER BREAKDOWN: Actor 1: Count Dracula – CRISTINEL HOGAS Count Dracula: A Transylvanian noble who bought a house in London and asked Jonathan Harker to come to his castle to do business with him. Actor 2: Jonathan Harker -- CARL DOLAMORE Harker: A solicitor sent to do business with Count Dracula; Mina's fiancé and prisoner in Dracula's castle. Actor 3: Wilhelmina ‘Mina’ Harker [née Murray] – HARRIET CLARE MAIN Mina: A schoolteacher and Jonathan Harker's fiancée. Actor 4: Lucy Westenra / Bride of Dracula 1 – GEORGIE MONTGOMERY Lucy: A 19-year-old aristocrat; Mina's best friend; Arthur's fiancée and Dracula's first victim. Dracula Bride 1: One of the 2 Vampires chastising Harker in Dracula’s castle. Actor 5: Dr Abraham Van Helsing – MITCH HOWELL Van Helsing: A Dutch professor; John Seward's teacher and Vampire hunter. -

Blood and Images in Dracula 2000

Journal of Dracula Studies Volume 8 2006 Article 3 2006 "The coin of our realm": Blood and Images in Dracula 2000 Alan S. Ambrisco University of Akron, Ohio Lance Svehla University of Akron, Ohio Follow this and additional works at: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/dracula-studies Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ambrisco, Alan S. and Svehla, Lance (2006) ""The coin of our realm": Blood and Images in Dracula 2000," Journal of Dracula Studies: Vol. 8 , Article 3. Available at: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/dracula-studies/vol8/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Research Commons at Kutztown University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Dracula Studies by an authorized editor of Research Commons at Kutztown University. For more information, please contact [email protected],. "The coin of our realm": Blood and Images in Dracula 2000 Cover Page Footnote Alan S. Ambrisco is an Associate Professor of English at The University of Akron. His research interests include medieval literature and the history of monsters. Lance Svehla is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Akron. He has published work in such journals as Teaching English in the Two-Year College and College Literature. This article is available in Journal of Dracula Studies: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/dracula-studies/vol8/ iss1/3 “The coin of our realm”: Blood and Images in Dracula 2000 Alan S. Ambrisco and Lance Svehla [Alan S. -

Renfield – in the Shadow of the Vampire at the Bakehouse Theatre, 2020

FRINGE REVIEW: RENFIELD – IN THE SHADOW OF THE VAMPIRE AT THE BAKEHOUSE THEATRE, 2020 English theatrical company Grist To The Mill Productions have a number of shows running throughout this year’s Adelaide Fringe. Renfield: In The Shadow Of The Vampire, is the newest addition to their repertoire and it had its world premiere at the Bakehouse Theatre on Thursday night. Written and performed by British actor, Ross Ericson, and directed by Michelle Yim, the play is a harrowing exploration of an individual’s descent into madness, presented through the experiences of the delusional character, Renfield, who featured in Bram Stoker’s classic gothic horror novel, Dracula. The action is set in the Carfax lunatic asylum run by Dr. John Seward as described in the original source text. Renfield, in this production, is first seen fronting a panel of medical experts and influential dignitaries, including Dr. Abraham Van Helsing and Quincy Adams, and British nobles. They are gathered together to assess whether Renfield can be considered as being cured and declared sane, so that he can subsequently be tried in court for his crimes against society. It’s a solo piece for Ericson. He plays the role of ‘narrator’, who cleverly contextualises events for the audience in extended rhyming verse, as well as assuming the part of Renfield, both in the present, as he argues his case to the panel, and in the past, as he relates his journey to self- understanding in a series of vivid flashbacks. Addressing the audience briefly after the show, Ericson suggested that the work is, to some degree, still in progress; and at times during the performance, the flow of dialogue in the frequent shifts between his character’s internal perspectives, did come across as tentative and the changes were not always clearly defined, This suggested that the writer/performer is still experimenting with the piece and is, as yet, undecided about how best to deliver the material he has written to achieve its optimal effect. -

Rosemary Ellen Guiley

vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page i The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page ii The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS Rosemary Ellen Guiley FOREWORD BY Jeanne Keyes Youngson, President and Founder of the Vampire Empire The Encyclopedia of Vampires, Werewolves, and Other Monsters Copyright © 2005 by Visionary Living, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guiley, Rosemary. The encyclopedia of vampires, werewolves, and other monsters / Rosemary Ellen Guiley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4684-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4381-3001-9 (e-book) 1. Vampires—Encyclopedias. 2. Werewolves—Encyclopedias. 3. Monsters—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BF1556.G86 2004 133.4’23—dc22 2003026592 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

By Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu

CARMILLA BY JOSEPH SHERIDAN LE FANU Irish Studies James MacKillop, Series Editor Other titles in the Irish series Collaborative Dubliners: Joyce in Dialogue Vicki Mahaffey, ed. Gender and Medicine in Ireland, 1700–1950 Margaret Preston and Margaret Ó hÓgartaigh, eds. Grand Opportunity: The Gaelic Revival and Irish Society, 1893–1910 Timothy G. McMahon Ireland in Focus: Film, Photography, and Popular Culture Eóin Flannery and Michael Griff n, eds. The Irish Bridget: Irish Immigrant Women in Domestic Service in America, 1840–1930 Margaret Lynch-Brennan Irish Theater in America: Essays on Irish Theatrical Diaspora John P. Harrington, ed. Joyce, Imperialism, and Postcolonialism Leonard Orr, ed. Making Ireland Irish: Tourism and National Identity since the Irish Civil War Eric G. E. Zuelow Memory Ireland, Volume 1: History and Modernity, and Volume 2: Diaspora and Memory Practices Oona Frawley, ed. The Midnight Court / Cúirt an Mheán Oíche Brian Merriman; David Marcus, trans.; Brian Ó Conchubhair, ed. Carmilla by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu A CRITICAL EDITION • edited and with an introduction by Kathleen Costello-Sullivan SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY PRESS Copyright © 2013 by Syracuse University Press Syracuse, New York 13244-5290 All Rights Reserved First Edition 2013 13 14 15 16 17 18 6 5 4 3 2 1 Illustrations courtesy of the Special Collections/Research Center, Syracuse University Library. ∞ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. For a listing of books published and distributed by Syracuse University Press, visit our website at SyracuseUniversityPress.syr.edu.