PAPER 3 Italy (1815–1871) and Germany (1815–1890) SECOND EDITION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German North Sea Ports' Absorption Into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914

From Unification to Integration: The German North Sea Ports' absorption into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914 Henning Kuhlmann Submitted for the award of Master of Philosophy in History Cardiff University 2016 Summary This thesis concentrates on the economic integration of three principal German North Sea ports – Emden, Bremen and Hamburg – into the Bismarckian nation- state. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, Emden, Hamburg and Bremen handled a major share of the German Empire’s total overseas trade. However, at the time of the foundation of the Kaiserreich, the cities’ roles within the Empire and the new German nation-state were not yet fully defined. Initially, Hamburg and Bremen insisted upon their traditional role as independent city-states and remained outside the Empire’s customs union. Emden, meanwhile, had welcomed outright annexation by Prussia in 1866. After centuries of economic stagnation, the city had great difficulties competing with Hamburg and Bremen and was hoping for Prussian support. This thesis examines how it was possible to integrate these port cities on an economic and on an underlying level of civic mentalities and local identities. Existing studies have often overlooked the importance that Bismarck attributed to the cultural or indeed the ideological re-alignment of Hamburg and Bremen. Therefore, this study will look at the way the people of Hamburg and Bremen traditionally defined their (liberal) identity and the way this changed during the 1870s and 1880s. It will also investigate the role of the acquisition of colonies during the process of Hamburg and Bremen’s accession. In Hamburg in particular, the agreement to join the customs union had a significant impact on the merchants’ stance on colonialism. -

Noise and Silence in Rigoletto's Venice

Cambridge Opera Journal, 31, 2-3, 188–210 © The Author(s), 2020. Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://cre ativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S0954586720000038 Noise and Silence in Rigoletto’s Venice ALESSANDRA JONES* Abstract: In this article I explore how public acts of defiant silence can work as forms of his- torical evidence, and how such refusals constitute a distinct mode of audio-visual attention and political resistance. After the Austrians reconquered Venice in August 1849, multiple observers reported that Venetians protested their renewed subjugation via theatre boycotts (both formal and informal) and a refusal to participate in festive occasions. The ostentatious public silences that met the daily Austrian military band concerts in the city’s central piazza became a ritual that encouraged foreign observers to empathise with the Venetians’ plight. Whereas the gondolier’s song seemed to travel separate from the gondolier himself, the piazza’s design instead encour- aged a communal listening coloured by the politics of the local cafes. In the central section of the article, I explore the ramifications of silence, resistance and disconnections between sight and sound as they shape Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, which premiered at Venice’s Teatro la Fenice in 1851. The scenes in Rigoletto most appreciated by the first Venetian audiences hinge on the power to observe and overhear, suggesting that early spectators experienced the opera through a mode of engagement born of the local material conditions and political circumstances. -

Locating the Wallachian Revolution of *

The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/./), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:./SX LOCATING THE WALLACHIAN REVOLUTION OF * JAMES MORRIS Emmanuel College, Cambridge ABSTRACT. This article offers a new interpretation of the Wallachian revolution of . It places the revolution in its imperial and European contexts and suggests that the course of the revolution cannot be understood without reference to these spheres. The predominantly agrarian principality faced different but commensurate problems to other European states that experienced revolution in . Revolutionary leaders attempted to create a popular political culture in which all citizens, both urban and rural, could participate. This revolutionary community formed the basis of the gov- ernment’s attempts to enter into relations with its Ottoman suzerain and its Russian protector. Far from attempting to subvert the geopolitical order, this article argues that the Wallachians positioned themselves as loyal subjects of the sultan and saw their revolution as a meeting point between the Ottoman Empire and European civilization. The revolution was not a staging post on the road to Romanian unification, but a brief moment when it seemed possible to realize internal regeneration on a European model within an Ottoman imperial framework. But the Europe of was too unstable for the revolutionaries to succeed. The passing of this moment would lead some to lose faith in both the Ottoman Empire and Europe. -

Victories Are Not Enough: Limitations of the German Way of War

VICTORIES ARE NOT ENOUGH: LIMITATIONS OF THE GERMAN WAY OF WAR Samuel J. Newland December 2005 Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. This publication is a work of the United States Government, as defined in Title 17, United States Code, section 101. As such, it is in the public domain and under the provisions of Title 17, United States Code, section 105, it may not be copyrighted. ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** My sincere thanks to the U.S. Army War College for approving and funding the research for this project. It has given me the opportunity to return to my favorite discipline, Modern German History, and at the same time, develop a monograph which has implications for today’s army and officer corps. In particular, I would like to thank the Dean of the U.S. Army War College, Dr. William Johnsen, for agreeing to this project; the Research Board of the Army War College for approving the funds for the TDY; and my old friend and colleague from the Militärgeschichliches Forschungsamt, Colonel (Dr.) Karl-Heinz Frieser, and some of his staff for their assistance. In addition, I must also thank a good former student of mine, Colonel Pat Cassidy, who during his student year spent a considerable amount of time finding original curricular material on German officer education and making it available to me. -

Otto Von Bismarck

Otto von Bismarck Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck Retrato de Otto von Bismarck 1871. Canciller de Alemania 21 de marzo de 1871-20 de marzo de 1890 Monarca Guillermo I (1871-1888) Federico III (1888) Guillermo II (1888-1890) Predecesor Primer Titular Sucesor Leo von Caprivi Primer ministro de Prusia 23 de septiembre de 1862-1 de enero de 1873 Predecesor Adolf zu Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen Sucesor Albrecht von Roon 9 de noviembre de 1873-20 de marzo de 1890 Predecesor Albrecht von Roon Sucesor Leo von Caprivi Datos personales Nacimiento 1 de abril de 1815 Schönhausen, Prusia Fallecimiento 30 de julio de 1898 (83 años) Friedrichsruh, Alemania Partido sin etiquetar Cónyuge Johanna von Puttkamer Hijos Herbert von Bismarck y Wilhelm von Bismarck Ocupación político, diplomático y jurista Alma máter Universidad de Gotinga Religión luteranismo Firma de Otto von Bismarck [editar datos en Wikidata] Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck-Schönhausen, Príncipe de Bismarck y Duque de Lauenburg (Schönhausen, 1 de abrilde 1815–Friedrichsruh, 30 de julio de 1898)1 conocido como Otto von Bismarck, fue un estadista, burócrata, militar, político yprosista alemán, considerado el fundador del Estado alemán moderno. Durante sus últimos años de vida se le apodó el «Canciller de Hierro» por su determinación y mano dura en la gestión de todo lo relacionado con su país,n. 1 que incluía la creación de un sistema de alianzas internacionales que aseguraran la supremacía de Alemania, conocido como el Reich.1 Cursó estudios de leyes y, a partir de 1835, trabajó en los tribunales -

Ap-6 . the Rubicon Is Crossed 191 Appendix 6 1) What Is the Rubicon

Ap-6 . The Rubicon is crossed 191 Appendix 6 1) What is the Rubicon? It is a stream near Rimini, Italy. 2) What is significant about the stream that crossing it is so well known? Neither crossing the Rubicon nor the people who cross it is necessarily significant. Julius Caesar made it significant by saying "the die is cast" and by ceremoniously crossing the Rubicon as a symbol of defiance to the orders of the ruler of Rome, Pompey, and the Roman government. They had ordered Julius to return to Rome by disbanding his army, as he returned from defeating Gaul. As Julius Caesar marched to Rome, Pompey fled. Eventually the Senate elected Julius dictator for life in 49 BC. In 44 BC Senator Brutus stabbed Julius, the benevolent duce (leader) to death (Kubly and Ross, 1961). 3) Why would the defiance of a dictator become the cry that so many revere? Julius Caesar was no simple dictator. He felt that he was a descendent of Jupiter. He studied and practiced law, and even was a Pontus Maximus (interpreter of the messages of the Gods) of Rome before marching as the general to subjugate Gaul (France). He always shared his exploits to the plebeians (landless Romans), who assembled in the Roman central town of activity (the Forum) as he marched along the Via Sacra (the sacred street of the Forum). He was well liked by the plebeians, though less so by the patricians (rich Romans including senators) of Republican Rome. He had a sense that he was going to reform the republic and make it more responsive to the Ap-6 . -

By Filippo Sabetti Mcgill University the MAKING of ITALY AS AN

THE MAKING OF ITALY AS AN EXPERIMENT IN CONSTITUTIONAL CHOICE by Filippo Sabetti McGill University THE MAKING OF ITALY AS AN EXPERIMENT IN CONSTITUTIONAL CHOICE In his reflections on the history of European state-making, Charles Tilly notes that the victory of unitary principles of organiza- tion has obscured the fact, that federal principles of organization were alternative design criteria in The Formation of National States in West- ern Europe.. Centralized commonwealths emerged from the midst of autonomous, uncoordinated and lesser political structures. Tilly further reminds us that "(n)othing could be more detrimental to an understanding of this whole process than the old liberal conception of European history as the gradual creation and extension of political rights .... Far from promoting (representative) institutions, early state-makers 2 struggled against them." The unification of Italy in the nineteenth century was also a victory of centralized principles of organization but Italian state- making or Risorgimento differs from earlier European state-making in at least three respects. First, the prospects of a single political regime for the entire Italian peninsula and islands generated considerable debate about what model of government was best suited to a population that had for more than thirteen hundred years lived under separate and diverse political regimes. The system of government that emerged was the product of a conscious choice among alternative possibilities con- sidered in the formulation of the basic rules that applied to the organi- zation and conduct of Italian governance. Second, federal principles of organization were such a part of the Italian political tradition that the victory of unitary principles of organization in the making of Italy 2 failed to obscure or eclipse them completely. -

DO AS the SPANIARDS DO. the 1821 PIEDMONT INSURRECTION and the BIRTH of CONSTITUTIONALISM Haced Como Los Españoles. Los Movimi

DO AS THE SPANIARDS DO. THE 1821 PIEDMONT INSURRECTION AND THE BIRTH OF CONSTITUTIONALISM Haced como los españoles. Los movimientos de 1821 en Piamonte y el origen del constitucionalismo PIERANGELO GENTILE Universidad de Turín [email protected] Cómo citar/Citation Gentile, P. (2021). Do as the Spaniards do. The 1821 Piedmont insurrection and the birth of constitutionalism. Historia y Política, 45, 23-51. doi: https://doi.org/10.18042/hp.45.02 (Reception: 15/01/2020; review: 19/04/2020; acceptance: 19/09/2020; publication: 01/06/2021) Abstract Despite the local reference historiography, the 1821 Piedmont insurrection still lacks a reading that gives due weight to the historical-constitutional aspect. When Carlo Alberto, the “revolutionary” Prince of Carignano, granted the Cádiz Consti- tution, after the abdication of Vittorio Emanuele I, a crisis began in the secular history of the dynasty and the kingdom of Sardinia: for the first time freedoms and rights of representation broke the direct pledge of allegiance, tipycal of the absolute state, between kings and people. The new political system was not autochthonous but looked to that of Spain, among the many possible models. Using the extensive available bibliography, I analyzed the national and international influences of that 24 PIERANGELO GENTILE short historical season. Moreover I emphasized the social and geographic origin of the leaders of the insurrection (i.e. nobility and bourgeoisie, core and periphery of the State) and the consequences of their actions. Even if the insurrection was brought down by the convergence of the royalist forces and the Austrian army, its legacy weighed on the dynasty. -

Networks of Modernity: Germany in the Age of the Telegraph, 1830–1880

OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 24/3/2021, SPi STUDIES IN GERMAN HISTORY Series Editors Neil Gregor (Southampton) Len Scales (Durham) Editorial Board Simon MacLean (St Andrews) Frank Rexroth (Göttingen) Ulinka Rublack (Cambridge) Joel Harrington (Vanderbilt) Yair Mintzker (Princeton) Svenja Goltermann (Zürich) Maiken Umbach (Nottingham) Paul Betts (Oxford) OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 24/3/2021, SPi OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 24/3/2021, SPi Networks of Modernity Germany in the Age of the Telegraph, 1830–1880 JEAN-MICHEL JOHNSTON 1 OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 24/3/2021, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Jean-Michel Johnston 2021 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2021 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. -

Italy, the Adriatic and the Balkans: from the Great War to the Eve of the Peace Conference

122 Caccamo Chapter 6 Italy, the Adriatic and the Balkans: From the Great War to the Eve of the Peace Conference Francesco Caccamo Background At the end of August 1914, one month after the Austrian attack on Serbia which began the Great War, the Italian foreign minister Marquis Antonino di Sangiuliano felt the need to explain to a German politician of his acquaintance the reasons why Antonio Salandra’s government had stepped back from the Triple Alliance and proclaimed neutrality. He relied on a sole argument, name- ly the fears and suspicions generated in Italy by Vienna’s policies towards South-Eastern Europe: [Italian public opinion] has always viewed Austria’s territorial ambitions in the Balkans and the Adriatic with mistrust; it has always sympathized with the weak who are threatened by the strong; it has always profoundly believed in the principles of liberalism and of nationality. It considered the real independence and territorial integrity of Serbia as a bulwark and an element of balance essential to Italy’s interests. It is against all of this that Austria’s aggression against Serbia has been directed, and it is this aggression which has led to the war.1 This explanation should be viewed cautiously, or at least in its context. An acute if casual observer, and Machiavellian on occasion, Sangiuliano hit the target when he highlighted the importance to Italy of the near regions of the eastern Adriatic and the Balkans, where the cultural networks of the Venetian Republic lived on and where the slow but inexorable decline of the Ottoman Empire had been the home of opportunities and dangers for many years.2 It was also 1 Sangiuliano to Bülow, 31 August 1914, Archivio Sonnino di Montespertoli, here used in the microfilm version preserved at the Archivio Centrale di Stato di Roma (hereafter ACS), bobina 47. -

The Ashgate Research Companion to Imperial Germany ASHGATE RESEARCH COMPANION

ASHGATE RESEARCH COMPANION THE ASHGatE RESEarCH COMPANION TO IMPERIAL GERMANY ASHGATE RESEARCH COMPANION The Ashgate Research Companions are designed to offer scholars and graduate students a comprehensive and authoritative state-of-the-art review of current research in a particular area. The companions’ editors bring together a team of respected and experienced experts to write chapters on the key issues in their speciality, providing a comprehensive reference to the field. The Ashgate Research Companion to Imperial Germany Edited by MattHEW JEFFERIES University of Manchester, UK © Matthew Jefferies 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Matthew Jefferies has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the editor of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East 110 Cherry Street Union Road Suite 3-1 Farnham Burlington, VT 05401-3818 Surrey, GU9 7PT USA England www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Ashgate research companion to Imperial Germany / edited by Matthew Jefferies. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4094-3551-8 (hardcover) – ISBN 978-1-4094-3552-5 -

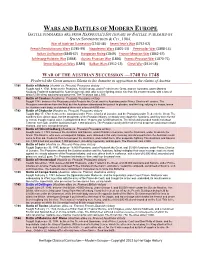

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners.