Low-Cost Options for Airborne Delivery of Contraband Into North Korea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D2492609215cd311123628ab69

Acknowledgements Publisher AN Cheongsook, Chairperson of KOFIC 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu. Seoul, Korea (130-010) Editor in Chief Daniel D. H. PARK, Director of International Promotion Department Editors KIM YeonSoo, Hyun-chang JUNG English Translators KIM YeonSoo, Darcy PAQUET Collaborators HUH Kyoung, KANG Byeong-woon, Darcy PAQUET Contributing Writer MOON Seok Cover and Book Design Design KongKam Film image and still photographs are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), GIFF (Gwangju International Film Festival) and KIFV (The Association of Korean Independent Film & Video). Korean Film Council (KOFIC), December 2005 Korean Cinema 2005 Contents Foreword 04 A Review of Korean Cinema in 2005 06 Korean Film Council 12 Feature Films 20 Fiction 22 Animation 218 Documentary 224 Feature / Middle Length 226 Short 248 Short Films 258 Fiction 260 Animation 320 Films in Production 356 Appendix 386 Statistics 388 Index of 2005 Films 402 Addresses 412 Foreword The year 2005 saw the continued solid and sound prosperity of Korean films, both in terms of the domestic and international arenas, as well as industrial and artistic aspects. As of November, the market share for Korean films in the domestic market stood at 55 percent, which indicates that the yearly market share of Korean films will be over 50 percent for the third year in a row. In the international arena as well, Korean films were invited to major international film festivals including Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Locarno, and San Sebastian and received a warm reception from critics and audiences. It is often said that the current prosperity of Korean cinema is due to the strong commitment and policies introduced by the KIM Dae-joong government in 1999 to promote Korean films. -

Virtual Conference Contents

Virtual Conference Contents 등록 및 발표장 안내 03 2020 한국물리학회 가을 학술논문발표회 및 05 임시총회 전체일정표 구두발표논문 시간표 13 포스터발표논문 시간표 129 발표자 색인 189 이번 호의 표지는 김요셉 (공동 제1저자), Yong Siah Teo (공동 제1저자), 안대건, 임동길, 조영욱, 정현석, 김윤호 회원의 최근 논문 Universal Compressive Characterization of Quantum Dynamics, Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 210401 (2020) 에서 모티 브를 채택했다. 이 논문에서는 효율적이고 신뢰할 수 있는 양자 채널 진단을 위한 적응형 압축센싱 방법을 제안하고 이를 실험 으로 시연하였다. 이번 가을학술논문발표회 B11-ap 세션에서 김요셉 회원이 관련 주제에 대해서 발표할 예정(B11.02)이다. 2 등록 및 발표장 안내 (Registration & Conference Room) 1. Epitome Any KPS members can download the pdf files on the KPS homepage. (http://www.kps.or.kr) 2. Membership & Registration Fee Category Fee (KRW) Category Fee (KRW) Fellow/Regular member 130,000 Subscription 1 journal 80,000 Student member 70,000 (Fellow/Regular 2 journals 120,000 Registration Nonmember (general) 300,000 member) Nonmember 150,000 1 journal 40,000 (invited speaker or student) Subscription Fellow 100,000 (Student member) 2 journals 60,000 Membership Regular member 50,000 Student member 20,000 Enrolling fee New member 10,000 3. Virtual Conference Rooms Oral sessions Special sessions Division Poster sessions (Zoom rooms) (Zoom rooms) Particle and Field Physics 01, 02 • General Assembly: 20 Nuclear Physics 03 • KPS Fellow Meeting: 20 Condensed Matter Physics 05, 06, 07, 08 • NPSM Senior Invited Lecture: 20 Applied Physics 09, 10, 11 Virtual Poster rooms • Heavy Ion Accelerator Statistical Physics 12 (Nov. 2~Nov. 6) Complex, RAON: 19 Physics Teaching 13 • Computational science: 20 On-line Plasma Physics 14 • New accelerator: 20 Discussion(mandatory): • KPS-KOFWST Young Optics and Quantum Electonics 15 Nov. -

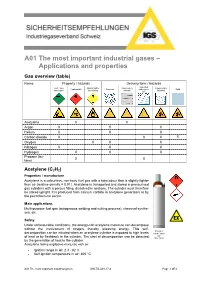

A01 the Most Important Industrial Gases – Applications and Properties

A01 The most important industrial gases – Applications and properties Gas overview (table) Name Property / hazards Delivery form / hazards Liquefied Inert / non- Oxidising/fire Dissolved (in Cryogenically Combustible Gaseous under pres- Solid flammable intensifying solvent) liquefied sure Acetylene X X Argon X X X Helium X X X Carbon dioxide X X X X Oxygen X X X Nitrogen X X X Hydrogen X X X Propane (bu- X X tane) Acetylene (C2H2) Properties / manufacture Acetylene is a colourless, non-toxic fuel gas with a faint odour that is slightly lighter than air (relative density = 0.91). Acetylene is transported and stored in pressurised gas cylinders with a porous filling, dissolved in acetone. The cylinder must therefore be stored upright. It is produced from calcium carbide in acetylene generators or by the petrochemical sector. Main applications Multi-purpose fuel gas (autogenous welding and cutting process), chemical synthe- ses, etc. Safety Under unfavourable conditions, the energy-rich acetylene molecule can decompose without the involvement of oxygen, thereby releasing energy. This self- Shoulder decomposition can be initiated when an acetylene cylinder is exposed to high levels colour “oxide red” of heat or by flashback in the cylinder. The start of decomposition can be detected RAL 3009 by the generation of heat in the cylinder. Acetylene forms explosive mixtures with air. Ignition range in air: 2.3 - 82 % Self-ignition temperature in air: 305 °C A01 The most important industrial gases IGS-TS-A01-17-d Page 1 of 4 Argon (Ar) Properties / manufacture Argon is a colourless, odourless, non-combustible gas, extremely inert noble gas and heavier than air (relative density = 1.78). -

Colonization of Venus

Conference on Human Space Exploration, Space Technology & Applications International Forum, Albuquerque, NM, Feb. 2-6 2003. Colonization of Venus Geoffrey A. Landis NASA Glenn Research Center mailstop 302-1 21000 Brook Park Road Cleveland, OH 44135 21 6-433-2238 geofrq.landis@grc. nasa.gov ABSTRACT Although the surface of Venus is an extremely hostile environment, at about 50 kilometers above the surface the atmosphere of Venus is the most earthlike environment (other than Earth itself) in the solar system. It is proposed here that in the near term, human exploration of Venus could take place from aerostat vehicles in the atmosphere, and that in the long term, permanent settlements could be made in the form of cities designed to float at about fifty kilometer altitude in the atmosphere of Venus. INTRODUCTION Since Gerard K. O'Neill [1974, 19761 first did a detailed analysis of the concept of a self-sufficient space colony, the concept of a human colony that is not located on the surface of a planet has been a major topic of discussion in the space community. There are many possible economic justifications for such a space colony, including use as living quarters for a factory producing industrial products (such as solar power satellites) in space, and as a staging point for asteroid mining [Lewis 19971. However, while the concept has focussed on the idea of colonies in free space, there are several disadvantages in colonizing empty space. Space is short on most of the raw materials needed to sustain human life, and most particularly in the elements oxygen, hydrogen, carbon, and nitrogen. -

2013 News Archive

Sep 4, 2013 America’s Challenge Teams Prepare for Cross-Country Adventure Eighteenth Race Set for October 5 Launch Experienced and formidable. That describes the field for the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta’s 18th America’s Challenge distance race for gas balloons. The ten members of the five teams have a combined 110 years of experience flying in the America’s Challenge, along with dozens of competitive years in the other great distance race, the Coupe Aéronautique Gordon Bennett. Three of the five teams include former America’s Challenge winners. The object of the America’s Challenge is to fly the greatest distance from Albuquerque while competing within the event rules. The balloonists often stay aloft more than two days and must use the winds aloft and weather systems to their best advantage to gain the greatest distance. Flights of more than 1,000 miles are not unusual, and the winners sometimes travel as far as Canada and the U.S. East Coast. This year’s competitors are: • Mark Sullivan and Cheri White, USA: Last year Sullivan, from Albuquerque, and White, from Austin, TX, flew to Beauville, North Carolina to win their second America’s Challenge (their first was in 2008). Their winning 2012 flight of 2,623 km (1,626 miles) ended just short of the East Coast and was the fourth longest in the history of the race. The team has finished as high as third in the Coupe Gordon Bennett (2009). Mark Sullivan, a multiple-award-winning competitor in both hot air and gas balloons and the American delegate to the world ballooning federation, is the founder of the America’s Challenge. -

Atmospheric Planetary Probes And

SPECIAL ISSUE PAPER 1 Atmospheric planetary probes and balloons in the solar system A Coustenis1∗, D Atkinson2, T Balint3, P Beauchamp3, S Atreya4, J-P Lebreton5, J Lunine6, D Matson3,CErd5,KReh3, T R Spilker3, J Elliott3, J Hall3, and N Strange3 1LESIA, Observatoire de Paris-Meudon, Meudon Cedex, France 2Department Electrical & Computer Engineering, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID, USA 3Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA 4University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA 5ESA/ESTEC, AG Noordwijk, The Netherlands 6Dipartment di Fisica, University degli Studi di Roma, Rome, Italy The manuscript was received on 28 January 2010 and was accepted after revision for publication on 5 November 2010. DOI: 10.1177/09544100JAERO802 Abstract: A primary motivation for in situ probe and balloon missions in the solar system is to progressively constrain models of its origin and evolution. Specifically, understanding the origin and evolution of multiple planetary atmospheres within our solar system would provide a basis for comparative studies that lead to a better understanding of the origin and evolution of our Q1 own solar system as well as extra-solar planetary systems. Hereafter, the authors discuss in situ exploration science drivers, mission architectures, and technologies associated with probes at Venus, the giant planets and Titan. Q2 Keywords: 1 INTRODUCTION provide significant design challenge, thus translating to high mission complexity, risk, and cost. Since the beginning of the space age in 1957, the This article focuses on the exploration of planetary United States, European countries, and the Soviet bodies with sizable atmospheres, using entry probes Union have sent dozens of spacecraft, including and aerial mobility systems, namely balloons. -

Rest of the Solar System” As We Have Covered It in MMM Through the Years

As The Moon, Mars, and Asteroids each have their own dedicated theme issues, this one is about the “rest of the Solar System” as we have covered it in MMM through the years. Not yet having ventured beyond the Moon, and not yet having begun to develop and use space resources, these articles are speculative, but we trust, well-grounded and eventually feasible. Included are articles about the inner “terrestrial” planets: Mercury and Venus. As the gas giants Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune are not in general human targets in themselves, most articles about destinations in the outer system deal with major satellites: Jupiter’s Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Saturn’s Titan and Iapetus, Neptune’s Triton. We also include past articles on “Space Settlements.” Europa with its ice-covered global ocean has fascinated many - will we one day have a base there? Will some of our descendants one day live in space, not on planetary surfaces? Or, above Venus’ clouds? CHRONOLOGICAL INDEX; MMM THEMES: OUR SOLAR SYSTEM MMM # 11 - Space Oases & Lunar Culture: Space Settlement Quiz Space Oases: Part 1 First Locations; Part 2: Internal Bearings Part 3: the Moon, and Diferent Drums MMM #12 Space Oases Pioneers Quiz; Space Oases Part 4: Static Design Traps Space Oases Part 5: A Biodynamic Masterplan: The Triple Helix MMM #13 Space Oases Artificial Gravity Quiz Space Oases Part 6: Baby Steps with Artificial Gravity MMM #37 Should the Sun have a Name? MMM #56 Naming the Seas of Space MMM #57 Space Colonies: Re-dreaming and Redrafting the Vision: Xities in -

Are Airships Making a Comeback? Nicolas Raymond

Mike Follows Are airships making a comeback? Nicolas Raymond Hot air balloons over When hot air balloons are propelled through the Quebec, Canada air rather than just being pushed along by the wind they are known as airships or dirigibles. The heyday of airships came to an abrupt end when the Hindenburg crashed dramatically in 1937. But, as Mike Follows explains, modern airships may Key words have a role in the future. density According to Archimedes’ Principle, any object forces immersed in a fluid receives an upthrust equal to the weight of the fluid it displaces. This can be Newton’s laws applied to lighter-than-air balloons: a balloon aircraft will descend if its weight exceeds that of the air displaced and rise if its weight is less. We can also think of this in terms of density. A balloon will rise if its overall density (balloon + air inside) is less than the density of the surrounding air. In hot-air balloons, the volume is constant and the density of air is varied by changing its temperature. Heating the air inside the envelope using the open flame from a burner in the gondola suspended beneath causes the air to expand and escape out through the bottom of the envelope. The top of the balloon usually has a vent of some sort, enabling the pilot to release hot air to slow an ascent. Colder, denser air will enter through the hole at the bottom of the envelope. Burning gas to give a hot air balloon greater lift 16 Catalyst February 2015 www.catalyststudent.org.uk Airships of the past airships. -

Evaluating Translations of Korean Literature: Current Status, Rationale, Purposes and Opportunities

Evaluating Translations of Korean Literature: Current Status, Rationale, Purposes and Opportunities Andreas Schirmer Zhodnotenie prekladov kórejskej literatúry: súčasný stav, odôvodnenie, zámery a príležitosti Resumé Štúdia ponúka poznatky, ktoré autor získal pri podrobnom čítaní prekladov kórejskej literatúry do nemeckého a anglického jazyka. Výsledky predstavujú príspevok ku komparatívnemu štúdiu jazykových a štylistických charakteristických znakov (štýl langue) týchto troch jazykov. Môžu poslúžiť pre potreby vzdelávania, keďže predstavujú konkrét- ne prípadové štúdie. Takisto môžu poslúžiť na zdôraznenie kultúrnych rozdielov v mys- lení a zdanlivo samozrejmých domnienkach na strane autorov ako aj prekladateľov. Výsledky tejto štúdie ponúkajú aj originálny prínos pre posúdenie poetológie významných kórejských spisovateľov. Keywords Korea, Literature · Translation · Translation Criticism · Translation Evalu- ation, Criteria 1 Evaluating how well or how poorly Korean literature is translated into Western languages is something that has not been done comprehensively until now. Access to evaluations written for those major institutions that support the translation of Korean literature into Western languages is deliberately restricted (the present writer attempted in vain to obtain permission to try such an »evaluation of evaluations«), which is regrettable.1 A plea is hereby made for This paper was written thanks to the support by an Academy of Korean Studies (KSPS) grant funded by the Korean Government (MOE): AKS-2011-BAA-2105. 1 These top secret evaluations are, all the more interestingly, written at several different stages: 272 SOS 12 · 2 (2013) increased transparency and the chance to openly discuss such evaluations. Notwithstanding the likely complications (any attempt at evaluating evaluations might, if not handled with the utmost delicacy, clash with the demand for analyst’s and translator’s anonymity—which of course has to be preserved), it would in principle be beneficial to enable the discussion of the verdict on a given translation. -

To What Extent Does Modern Technology Address the Problems of Past

To what extent does modern technology address the problems of past airships? Ansel Sterling Barnes Today, we have numerous technologies we take for granted: electricity, easy internet access, wireless communications, vast networks of highways crossing the continents, and flights crisscrossing the globe. Flight, though, is special because it captures man’s imagination. Humankind has dreamed of flight since Paleolithic times, and has achieved it with heavier-than-air craft such as airplanes and helicopters. Both of these are very useful and have many applications, but for certain jobs, these aircraft are not the ideal option because they are loud and waste energy. Luckily, there is an alternative to energy hogs like airplanes or helicopters, a lighter-than-air craft that predates both: airships! Airships do not generate their own lift through sheer power like heavier-than-air craft. They are airborne submarines of a sort that use a different lift source: gas. They don’t need to use the force of moving air to lift them from the ground, so they require very little energy to lift off or to fly. Unfortunately, there were problems with past airships; problems that were the reason for the decline of airships after World War II: cost, pilot skill, vulnerability to weather, complex systems control, materials, size, power source, and lifting gas. This begs the question: To what extent does modern technology address the problems of past airships? With today’s technology, said problems can be managed. Most people know lighter-than-air craft by one name or another: hot air balloons, blimps, dirigibles, zeppelins, etc. -

Diasporic P'ungmul in the United States

Diasporic P’ungmul in the United States: A Journey between Korea and the United States DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Soo-Jin Kim Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2011 Committee: Professor Udo Will, Advisor Associate Professor Chan E. Park Assistant Professor Danielle Fosler-Lussier Copyright by Soo-Jin Kim 2011 Abstract This study contributes to understanding diaspora and its music cultures by examining the Korean genre of p’ungmul as a particular site of continuous and dynamic cultural socio-political exchange between the homeland and the host society. As practiced in Los Angeles and New York City, this genre of percussion music and dance is shaped by Korean cultural politics, intellectual ideologies and institutions as p’ungmul practitioners in the United States seek performance aesthetics that fit into new performance contexts. This project first describes these contexts by tracing the history of Korean emigration to the United States and identifying the characteristics of immigrant communities in Los Angeles and New York City. While the p’ungmul troupes developed by Korean political refugees, who arrived during the 1980s, show the influence of the minjung cultural movement in Korea, cultural politics of the Korean government also played an important role in stimulating Korean American performers to learn traditional Korean performing arts by sending troupes to the United States. The dissertation then analyzes the various methods by which p’ungmul is transmitted in the United States, including the different methods of teaching and learning p’ungmul—writing verbalizations of instrumental sounds on paper, score, CD/DVD, and audio/video files found on the internet—and the cognitive consequences of those methods. -

Gas Division Newsletter

GAS DIVISIONH NEWSLETTER Official Publication of the BFA Gas Division Volume 1, Issue 2 Copyright Peter Cuneo & Barbara Fricke, 2000 Summer 2000 DANVILLE by Barbara Fricke The invitation went out for the National Gas Balloon Race to be held with the Oldsmobile Balloon Classic Illinois in Danville, Illinois. It would be a BFA sanctioned 3-part task race instead of a distance race. Ten balloons would compete. The pilots and co-pilots who registered, according to the rally's web site ( www.balloonclassic.org ), were: Troy Bradley and Bruce Hale Rusty Elwell and Don Weeks Barbara Fricke, Ray Bair and Danni Suskin Jim Hershend and Jack Holland David Levin and George Ibach Bert Padelt and Jack Edling Johnny Petrehn and Sam Parks The first briefing was on Thursday evening. Shane Robinson, Paul Morlock and Charles Page Not much said, since weather was the main concern Stan Wereschuk and Ron Martin and the weatherman was unavailable. The flags in Randy Woods and Ted Stanley front of the hotel were almost straight out. Friday morning resulted in the only pictures taken relating to gas ballooning. The organizers had arranged for many helpers with the big mound of sand. Friday's noon briefing was positive about an evening flight. The 7:00 pm briefing put the flight on hold. The later briefing called the Friday flight off – too windy. It would have been a "Denver" windy inflation and a flight towards, if not over, Lake Erie with sunrise while over the lake. Saturday's noon briefing tried to be positive, while the weather channel was forecasting evening thundershowers.