Paradigm Lost? Youth and Pop in the 90S Rupa Huq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indie Mixtape 20 Q&A Is with Proper., Who Can Sing All the Words to Every Kanye and Say Anything Album (Even the Bad Ones)

:: View email as a web page :: Chuck Klosterman once observed that every straight American man “has at least one transitionary period in his life when he believes Led Zeppelin is the only good band that ever existed.” Typically, this “Zeppelin phase” occurs in one’s teens, when a band that sings lasciviously about squeezing lemons while contemplating hobbits aligns with the surging hormones of the listener. But what about when you hit your early 30s? Is there a band that corresponds with graying beards and an encroaching sense of mortality? We believe, based on anecdotal evidence, that this band is the Grateful Dead. So many people who weren’t Dead fans when Jerry Garcia was alive have come to embrace the band, including many people in the indie-rock community, whether it’s Ezra Koenig of Vampire Weekend, Jim James of My Morning Jacket, or scores of others. Check out this piece on why the Dead is so popular now, even as the 25th anniversary of Garcia’s death looms, and let us know why you like them on Twitter. -- Steven Hyden, Uproxx Cultural Critic and author of This Isn't Happening: Radiohead's "Kid A" And The Beginning Of The 21st Century PS: Was this email forwarded to you? Join the band here. In case you missed it... Our YouTube channel just added a swath official music videos from Tori Amos and Faith No More. After a handful of delays, we now have an official release date for the new album from The Killers, as well as a new song. -

Lotus Infuses Downtown Bloomington with Global

FOR MORE INFORMATION: [email protected] || 812-336-6599 || lotusfest.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 8/26/2016 LOTUS INFUSES DOWNTOWN BLOOMINGTON WITH GLOBAL MUSIC Over 30 international artists come together in Bloomington, Indiana, for the 23rd annual Lotus World Music & Arts Festival. – COMPLETE EVENT DETAILS – Bloomington, Indiana: The Lotus World Music & Arts Festival returns to Bloomington, Indiana, September 15-18. Over 30 international artists from six continents and 20 countries take the stage in eight downtown venues including boisterous, pavement-quaking, outdoor dance tents, contemplative church venues, and historic theaters. Representing countries from A (Argentina) to Z (Zimbabwe), when Lotus performers come together for the four-day festival, Bloomington’s streets fill with palpable energy and an eclectic blend of global sound and spectacle. Through music, dance, art, and food, Lotus embraces and celebrates cultural diversity. The 2016 Lotus World Music & Arts Festival lineup includes artists from as far away as Finland, Sudan, Ghana, Lithuania, Mongolia, Ireland, Columbia, Sweden, India, and Israel….to as nearby as Virginia, Vermont, and Indiana. Music genres vary from traditional and folk, to electronic dance music, hip- hop-inflected swing, reggae, tamburitza, African retro-pop, and several uniquely branded fusions. Though US music fans may not yet recognize many names from the Lotus lineup, Lotus is known for helping to debut world artists into the US scene. Many 2016 Lotus artists have recently been recognized in both -

Swervedriver Never Lose That Feeling Mp3, Flac, Wma

Swervedriver Never Lose That Feeling mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Never Lose That Feeling Country: UK Released: 1992 Style: Alternative Rock, Indie Rock, Shoegaze MP3 version RAR size: 1123 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1535 mb WMA version RAR size: 1377 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 243 Other Formats: AC3 XM AA WMA DTS DMF ASF Tracklist Hide Credits A Never Lose That Feeling/Never Learn B1 Scrawl And Scream The Watchmakers Hands B2 Engineer – Philip AmesGuitar [Pedal Steel] – Patrick Arbruthnot* B3 Never Lose That Feeling Companies, etc. Distributed By – Pinnacle Phonographic Copyright (p) – Creation Records Copyright (c) – Creation Records Pressed By – MPO Published By – EMI Music Published By – EMI Songs Engineered At – Greenhouse Studio, London Mixed At – Matrix Studios Mixed At – Battery Studios, London Credits Mastered By – Porky Mixed By – Alan Moulder Producer, Engineer – Alan Moulder (tracks: A, B1, B3) Producer, Written-By, Arranged By – Swervedriver Saxophone – Stuart Dace* (tracks: A, B3) Notes Engineered at The Greenhouse Studios A, B1, and B3 Mixed at Matrix Studios B2 Mixed at Battery Studios Stuart Dace courtesy of Deep Joy Inc (Worldwide) Patrick Arbruthnot courtesy of The Rockingbirds and Heavenly A Creation Records Product Printed on centre labels: Made In France Printed on rear sleeve: Made in England ℗ & © 1992 Creation Records Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 5 017556 201206 Matrix / Runout (A side runout etched): CRE 120 T A1 IT'S A PORKY PRIME CUT. MPO IS THIS A COINCIDENCE OR WHAT? Matrix / Runout (B side runout etched): CRE 120 T B1 PORKY. MPO THE CHICKENS ARE DANCING. -

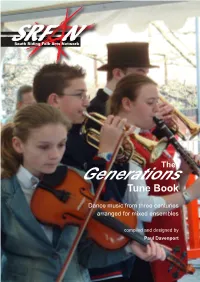

The Generations Tunebook Was Born of Necessity During the Course of an Educational Initiative Called, ‘The Generations Project’

South Riding Folk Arts Network The Generations Tune Book Dance music from three centuries arranged for mixed ensembles compiled and designed by Paul Davenport The Generations Tune Book The Generations Tune Book Dance music from three centuries arranged for mixed ensembles compiled and designed by Paul Davenport South Riding Folk Arts Network © 2005 The Generations Tune Book Introduction The Generations Tunebook was born of necessity during the course of an educational initiative called, ‘The Generations Project’. The project itself was initially, a simple exercise in Citizenship in a large South Yorkshire comprehensive school. The motivation behind this was to place teenagers at the heart of their community. The results of this venture had repercussions which are still being felt in the small mining town of Maltby which lies in the borough of Rotherham, not far from Sheffield. In 2002, the music department at Maltby Comprehensive School in partnership with the South Riding Folk Arts Network set about the task of teaching a group of 13 and 14 years old students the longsword dance. In this undertaking much support and encouragement was given by the national folk organisation, the English Folk Dance & Song Society. A group of students learned the dance whilst others learned to play the tunes to accompany the performance. Financial support from the school’s PTA allowed Head of Art, Liz Davenport, to create the striking costumes worn by the dancers. More support appeared in the form of folk arts development agency Folk South West who generously discounted their ‘College Hornpipe’ tunebook for the project. Players of orchestral instruments suddenly found themselves being extended by the apparently ‘simple’ melodies arranged by Paul Burgess. -

Swivel-Eyed Loons Had Found Their Cheerleader at Last: Like Nobody Else, Boris Could Put a Jolly Gloss on Their Ugly Tale of Brexit As Cultural Class- War

DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540141 FPSC Model Papers 50th Edition (Latest & Updated) By Imtiaz Shahid Advanced Publishers For Order Call/WhatsApp 03336042057 - 0726540141 CSS Solved Compulsory MCQs From 2000 to 2020 Latest & Updated Order Now Call/SMS 03336042057 - 0726540141 Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power & Peace By Hans Morgenthau FURTHER PRAISE FOR JAMES HAWES ‘Engaging… I suspect I shall remember it for a lifetime’ The Oldie on The Shortest History of Germany ‘Here is Germany as you’ve never known it: a bold thesis; an authoritative sweep and an exhilarating read. Agree or disagree, this is a must for anyone interested in how Germany has come to be the way it is today.’ Professor Karen Leeder, University of Oxford ‘The Shortest History of Germany, a new, must-read book by the writer James Hawes, [recounts] how the so-called limes separating Roman Germany from non-Roman Germany has remained a formative distinction throughout the post-ancient history of the German people.’ Economist.com ‘A daring attempt to remedy the ignorance of the centuries in little over 200 pages... not just an entertaining canter -

SOMERSET FOLK All Who Roam, Both Young and Old, DECEMBER TOP SONGS CLASSICAL Come Listen to My Story Bold

Folk Singing Broadsht.2 5/4/09 8:47 am Page 1 SOMERSET FOLK All who roam, both young and old, DECEMBER TOP SONGS CLASSICAL Come listen to my story bold. 400 OF ENGLISH COLLECTED BY For miles around, from far and near, YEARS FOLK MUSIC TEN FOLK They come to see the rigs o’ the fair, 11 Wassailing SOMERSET CECIL SHARP 1557 Stationers’ Company begins to keep register of ballads O Master John, do you beware! Christmastime, Drayton printed in London. The Seeds of Love Folk music has inspired many composers, and And don’t go kissing the girls at Bridgwater Fair Mar y Tudor queen. Loss of English colony at Calais The Outlandish Knight in England tunes from Somerset singers feature The lads and lasses they come through Tradtional wassailing 1624 ‘John Barleycorn’ first registered. John Barleycorn in the following compositions, evoking the very From Stowey, Stogursey and Cannington too. essence of England’s rural landscape: can also be a Civil Wars 1642-1650, Execution of Charles I Barbara Allen SONG COLLECTED BY CECIL SHARP FROM visiting 1660s-70s Samuel Pepys makes a private ballad collection. Percy Grainger’s passacaglia Green Bushes WILLIAM BAILEY OF CANNINGTON AUGUST 8TH 1906 Lord Randal custom, Restoration places Charles II on throne was composed in 1905-6 but not performed similar to carol The Wraggle Taggle Gypsies 1765 Reliques of Ancient English Poetry published by FOLK 5 until years later. It takes its themes from the 4 singing, with a Thomas Percy. First printed ballad collection. Dabbling in the Dew ‘Green Bushes’ tune collected from Louie bowl filled with Customs, traditions & glorious folk song Mozart in London As I walked Through the Meadows Hooper of Hambridge, plus a version of ‘The cider or ale. -

Southwark-Life-Summer-2019.Pdf

Southwark LifeSummer 2019 An inspiration Celebrating Southwark’s rising stars Borough of opportunity How to follow your dreams New homes, schools and salons Transforming our borough for everyone PLUS Events and fun in the sun this summer Your magazine from Southwark Council Summer 2019 Contents welcome... 4 Need to know – News from the council and across the borough Southwark is a great place to be young: to find your feet, 7 Sumner Road – We visit the discover your passion, and gain the skills you need for a happy brand new council homes on and rewarding life. This summer edition of Southwark Life is Sumner Road dedicated to inspiration and opportunity. We tell the stories 8 Our inspirational young of some of our incredible young people who have worked people – Our bumper feature hard to overcome barriers and excel in their chosen field, on inspiring young people from and also hear from some inspirational adults with sound around the borough advice on how to get on in life. I hope young people will 17 Blast from the past – We find plenty here to spark their curiosity, and give them chat to a resident who spotted confidence to chase their dreams. herself in a historic photo display As the long summer holidays approach, there’s no reason 18 Inspiring adults – Meet three local people why any child or young person should find themselves at a loose who have messages for our end in Southwark. From free entry to world class galleries and younger generation events, to award-winning parks, free swim and gym sessions at all 24 Southwark Presents – our leisure centres, and fun things happening at all our libraries, Music, plays and exhibitions there is something exciting happening on our doorstep every day. -

'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Glasgow School of Art: RADAR 'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir) David Sweeney During the Britpop era of the 1990s, the name of Mike Leigh was invoked regularly both by musicians and the journalists who wrote about them. To compare a band or a record to Mike Leigh was to use a form of cultural shorthand that established a shared aesthetic between musician and filmmaker. Often this aesthetic similarity went undiscussed beyond a vague acknowledgement that both parties were interested in 'real life' rather than the escapist fantasies usually associated with popular entertainment. This focus on 'real life' involved exposing the ugly truth of British existence concealed behind drawing room curtains and beneath prim good manners, its 'secrets and lies' as Leigh would later title one of his films. I know this because I was there. Here's how I remember it all: Jarvis Cocker and Abigail's Party To achieve this exposure, both Leigh and the Britpop bands he influenced used a form of 'real world' observation that some critics found intrusive to the extent of voyeurism, particularly when their gaze was directed, as it so often was, at the working class. Jarvis Cocker, lead singer and lyricist of the band Pulp -exemplars, along with Suede and Blur, of Leigh-esque Britpop - described the band's biggest hit, and one of the definitive Britpop songs, 'Common People', as dealing with "a certain voyeurism on the part of the middle classes, a certain romanticism of working class culture and a desire to slum it a bit". -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Student Lounge Revamped

The Pride http://www.csusm.edu/pride California State University, San Marcos Vol VIII No. 5/ Tuesday, September 26,2000 Faculty Files Grievance By: Jayne Braman istration and faculty. University's Convocation, Pride Staff The "faculty workload issue" President Gonzalez stated, "We revolves around a grievance filed are a CSU campus and we do have Students have many factors by the San Marcos chapter of to follow system-wide guidelines to consider when deciding on the faculty union, the California and operate within our funding which college to attend. Many Faculty Association (CFA), which formula which is predicated on CSUSM students credit the small is pending arbitration scheduled 15 units per Full Time Equivalent classes, the writing requirement, for October 28. Although the Student (FTES) and 12 Direct and the availability of professors details of the arbitration are not Weighted Teaching Units (WTU) as factors that ultimately add made public, the outcome of this for faculty." value to their education as well hearing will set a precedent that "The faculty argues that fund- as to their degrees. Students have will determine the future direc- ing increases depend strictly on also noted that the reputation tion of faculty workload. FTES, not on faculty teaching 12, of the institution will continue CSUSM President Alexander units," according to Dr. George to influence the value of their Gonzalez explains, "Faculty is Diehr, local union CFA President degrees long after they leave this contracted to work twelve (12) and Professor of Management campus. credit hours per semester." Science. "In fact," Diehr con- The window of opportunity Gonzalez continues, "This labor tends, "there is no mention any- is still wide open for CSUSM contract is part of a collective- where of faculty being required to to decide its future direction. -

Sandspur, Vol 98 No 17, February 19, 1992

University of Central Florida STARS The Rollins Sandspur Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida 2-19-1992 Sandspur, Vol 98 No 17, February 19, 1992 Rollins College Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rollins Sandspur by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rollins College, "Sandspur, Vol 98 No 17, February 19, 1992" (1992). The Rollins Sandspur. 1725. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/1725 THESANDSPUR Volume 98 Issue #17 Rollins College-Winter Park, Florida February 19, 1992 Family Weekend a hit across campus ByJENNIFER LEIGH HlLLEY Sandspur Staff Alice Ann Hardee also assisted in registration, and commented, "It's nice The weekend of February 14,1992, to see the parents doing stuff with the marked more than Valentine's Day kids, like in the tennis and golf tourna for Rollins students and families. ments." Titled "Rollins 'Round the World", Alumni House was all abuzz with this year's family weekend offered a families signing up, gathering bro unique opportunity for parents of our chures on the college and surrounding students to become a part of the col community, and chatting amiably lege experience. This year's event about the upcoming events. was a rousing success. Of parental response, Edith Mo Co=headed by Tony Tambascia of rales, Administrative Assistant in De the Dean's Office and Holly Loomis velopment, said, "We've seen a lot of of the Rollins Fund Office, the good, positive comments from the weekend included many athletic parents. -

Is Rock Music in Decline? a Business Perspective

Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences Bachelor of Business Administration International Business and Logistics 1405484 22nd March 2018 Abstract Author(s) Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Title Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Number of Pages 45 Date 22.03.2018 Degree Bachelor of Business Administration Degree Programme International Business and Logistics Instructor(s) Michael Keaney, Senior Lecturer Rock music has great importance in the recent history of human kind, and it is interesting to understand the reasons of its de- cline, if it actually exists. Its legacy will never disappear, and it will always be a great influence for new artists but is important to find out the reasons why it has become what it is in now, and what is the expected future for the genre. This project is going to be focused on the analysis of some im- portant business aspects related with rock music and its de- cline, if exists. The collapse of Gibson guitars will be analyzed, because if rock music is in decline, then the collapse of Gibson is a good evidence of this. Also, the performance of independ- ent and major record labels through history will be analyzed to understand better the health state of the genre. The same with music festivals that today seem to be increasing their popularity at the expense of smaller types of live-music events. Keywords Rock, music, legacy, influence, artists, reasons, expected, fu- ture, genre, analysis, business, collapse,