Metamemories of Memory Researchers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky and Robert A. Bjork Introduction Memory has been of interest to scholars and laypeople alike for over 2,000 years. In a rather gruesome example from antiquity, Cicero tells the story of Simonides (557– 468 BC), who discovered the method of loci, which is a powerful mental mnemonic for enhancing one’s memory. Simonides was at a banquet of a nobleman, Scopas. To honor him, Simonides sang a poem, but to Scopas’s chagrin, the poem also honored two young men, Castor and Pollux. Being upset, Scopas told Simonides that he was to receive only half his wage. Simonides was later called from the banquet, and legend has it that the banquet room collapsed, and all those inside were crushed. To help bereaved families identify the victims, Simonides reportedly was able to name every- one according to the place where they sat at the table, which gave him the idea that order brings strength to our memories and that to employ this ability people “should choose localities, then form mental images of things they wanted to store in their memory, and place these in the localities” (Cicero, 2001). Tis example highlights an early discovery that has had important applied impli- cations for improving the functioning of memory (see, e.g., Yates, 1997). Memory theory was soon to follow. Aristotle (385–322 BC) claimed that memory arises from three processes: Events are associated (1) through their relative similarity or (2) rela- tive dissimilarity and (3) when they co-occur together in space and time. -

Mnemonics in a Mnutshell: 32 Aids to Psychiatric Diagnosis

Mnemonics in a mnutshell: 32 aids to psychiatric diagnosis Clever, irreverent, or amusing, a mnemonic you remember is a lifelong learning tool ® Dowden Health Media rom SIG: E CAPS to CAGE and WWHHHHIMPS, mnemonics help practitioners and trainees recall Fimportant lists (suchCopyright as criteriaFor for depression,personal use only screening questions for alcoholism, or life-threatening causes of delirium, respectively). Mnemonics’ effi cacy rests on the principle that grouped information is easi- er to remember than individual points of data. Not everyone loves mnemonics, but recollecting diagnostic criteria is useful in clinical practice and research, on board examinations, and for insurance reimbursement. Thus, tools that assist in recalling di- agnostic criteria have a role in psychiatric practice and IMAGES teaching. JUPITER In this article, we present 32 mnemonics to help cli- © nicians diagnose: • affective disorders (Box 1, page 28)1,2 Jason P. Caplan, MD Assistant clinical professor of psychiatry • anxiety disorders (Box 2, page 29)3-6 Creighton University School of Medicine 7,8 • medication adverse effects (Box 3, page 29) Omaha, NE • personality disorders (Box 4, page 30)9-11 Chief of psychiatry • addiction disorders (Box 5, page 32)12,13 St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center Phoenix, AZ • causes of delirium (Box 6, page 32).14 We also discuss how mnemonics improve one’s Theodore A. Stern, MD Professor of psychiatry memory, based on the principles of learning theory. Harvard Medical School Chief, psychiatric consultation service Massachusetts General Hospital How mnemonics work Boston, MA A mnemonic—from the Greek word “mnemonikos” (“of memory”)—links new data with previously learned information. -

How We Learn: Memory & the Brain

How We Learn: Memory & the Brain or Where did I put those keys? CHARLES J. VELLA, PHD 2018 Proust & his Madeleine: Olfaction and Memory "I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touch my palate than a shudder ran trough me and I sopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure invaded my senses..... And suddenly the memory revealed itself. “ Marcel Proust À la recherche du temps perdu (known in English as: In Search of Lost Time or Remembrance of Things Past): 7 Volumes, 4000 pp. Proustian Effect: fragrances elicit more emotional and evocative memories than other memory cues Study: Proustian Products are Preferred: The Relationship Between Odor-Evoked Memory and Product Evaluation: Lotions preferred if they evoke personal emotional memories Memory Determines your sense of self Determines your ability to plan for future Enables you to remember your past Learning: Ability to learn new things Learning is a restless, piecemeal, subconscious, sneaky process that occurs all the time, when we are awake and when we are asleep. Older Explanation of Memory ATTENTION PROCESSING ENCODING STORAGE RETRIEVAL William James: "My experience is what I agree to attend to.“ Tip #1: There is no memory without first paying attention. Multiple Historical Metaphors for Memory based on then current technology •In Plato’s Theaetetus, metaphor of a stamp on wax • 1904 the German scholar Richard Semon: the engram. • Photograph • Tape recorder • Mirror • Hard drive • Neural network False Assumption: perfect image or recording, lasts forever Purpose of Memory We think of memory as a record of our past experience. -

Handbook of Metamemory and Memory Evolution of Metacognition

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 29 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Handbook of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky, Robert A. Bjork Evolution of Metacognition Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203805503.ch3 Janet Metcalfe Published online on: 28 May 2008 How to cite :- Janet Metcalfe. 28 May 2008, Evolution of Metacognition from: Handbook of Metamemory and Memory Routledge Accessed on: 29 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203805503.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Evolution of Metacognition Janet Metcalfe Introduction The importance of metacognition, in the evolution of human consciousness, has been emphasized by thinkers going back hundreds of years. While it is clear that people have metacognition, even when it is strictly defined as it is here, whether any other animals share this capability is the topic of this chapter. -

Hippocampal–Caudate Nucleus Interactions Support Exceptional Memory Performance

Brain Struct Funct DOI 10.1007/s00429-017-1556-2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Hippocampal–caudate nucleus interactions support exceptional memory performance Nils C. J. Müller1 · Boris N. Konrad1,2 · Nils Kohn1 · Monica Muñoz-López3 · Michael Czisch2 · Guillén Fernández1 · Martin Dresler1,2 Received: 1 December 2016 / Accepted: 24 October 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Participants of the annual World Memory competitive interaction between hippocampus and caudate Championships regularly demonstrate extraordinary mem- nucleus is often observed in normal memory function, our ory feats, such as memorising the order of 52 playing cards findings suggest that a hippocampal–caudate nucleus in 20 s or 1000 binary digits in 5 min. On a cognitive level, cooperation may enable exceptional memory performance. memory athletes use well-known mnemonic strategies, We speculate that this cooperation reflects an integration of such as the method of loci. However, whether these feats the two memory systems at issue-enabling optimal com- are enabled solely through the use of mnemonic strategies bination of stimulus-response learning and map-based or whether they benefit additionally from optimised neural learning when using mnemonic strategies as for example circuits is still not fully clarified. Investigating 23 leading the method of loci. memory athletes, we found volumes of their right hip- pocampus and caudate nucleus were stronger correlated Keywords Memory athletes · Method of loci · Stimulus with each other compared to matched controls; both these response learning · Cognitive map · Hippocampus · volumes positively correlated with their position in the Caudate nucleus memory sports world ranking. Furthermore, we observed larger volumes of the right anterior hippocampus in ath- letes. -

The Art of Loci: Immerse to Memorize

The Art of Loci: Immerse to Memorize Anne Vetter, Daniel Gotz,¨ Sebastian von Mammen Games Engineering, University of Wurzburg,¨ Germany fanne.vetter,[email protected], [email protected] Abstract—There are uncountable things to be remembered, but assistance during comprehension (R6) of the information, e.g. most people were never shown how to memorize effectively. With by means of verbalization, should follow suit. Due to the this paper, the application The Art of Loci (TAoL) is presented, heterogeneity of learners, the applied process and methods to provide the means for efficient and fun learning. In a virtual reality (VR) environment users can express their study material should be individualized (R7) and strike a productive balance visually, either creating dimensional mind maps or experimenting between user’s choices and imposed learning activities (locus with mnemonic strategies, such as mind palaces. We also present of control) (R8). For example, users should be able to control common memorization techniques in light of their underlying the pace of learning. Learning environments should arouse the pedagogical foundations and discuss the respective features of intrinsic motivation of the user (R9). Fostering an awareness TAoL in comparison with similar software applications. of the learner’s cognition and thus reflection on their learning I. INTRODUCTION process and strategies is also beneficial (metacognition) (R10). Further, a constructivist learning approach can be realized by Before writing was common, information could only be the means to create artefacts such as representations, symbols preserved by memorization. Major ancient literature like The or cues (R11). Finally, cooperative and collaborative learning Iliad and The Odyssey were memorized, passed on through environments can benefit the learning process (R12). -

CHAPTER 6: MEMORY STRATEGIES: MNEMONIC DEVICES in Order to Remember Information, You First Have to Find It Somewhere in Your Memory

CHAPTER 6: MEMORY STRATEGIES: MNEMONIC DEVICES In order to remember information, you first have to find it somewhere in your memory. To be successful in college you need to use active learning strategies that help you store information and retrieve it. Mnemonic devices can help you do that. Mnemonics are techniques for remembering information that is otherwise difficult to recall. The idea behind using mnemonics is to encode complex information in a way that is much easier to remember. Two common types of mnemonic devices are acronyms and acrostics. Acronyms Acronyms are words made up of the first letters of other words. As a mnemonic device, acronyms help you remember the first letters of items in a list, which in turn helps you remember the list itself. Instructor OLC to accompany 100% Online Student Success 1 Examples The following are examples of popular mnemonic acronyms: HOMES Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior Names of the Great Lakes FACE The letters of the treble clef notes in the spaces from bottom to top spells “FACE”. ROY G. BIV Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Colors of the spectrum Violet MRS GREN Movement, Respiration, Sensitivity, Growth, Common attributes of living Reproduction, Excretion, Nutrition things Create Your Own Acronym Now think of a few words you need to remember. This could be related to your studies, your work, or just a subject of interest. Five steps to creating acronyms are*: 1. List the information you need to learn in meaningful phrases. 2. Circle or underline a keyword in each phrase. 3. Write down the first letter of each keyword. -

Chapter 16 Improving Your Memory + 2 Tips for Selecting Passwords

+ Chapter 16 Improving Your Memory + 2 Tips for Selecting Passwords Use a transformation of some memorable cue involving a mix of letters and symbols Keep a record of all passwords in a place to which only you have access (e.g. a safe deposit box) It is easier to recall the location of a hidden object when the location is likely than when it is unexpected + 3 Popular Mnemonic Aids Harris (1980) surveyed housewives and students on their mnemonic use: Both groups used largely similar techniques; however, Students were more likely to write on their hands Housewives were more likely to write on calendars External aids (e.g. diaries, calendars, lists, and timers) were especially popular …Today we have laptops, PDAs, and mobile telephones Very few internal mnemonics were reported These are especially useful in situations that ban external aids + 4 Memory Experts Shereshevskii The Mind of a Mnemonist by Luria A Russian with an amazing memory A former journalist who never took notes but could repeat back quotes verbatim Had seemingly limitless memory for: Digits (100+) Nonsense syllables Foreign-language poetry Complex figures Complex scientific formulae His memory relied heavily on imagery and synesthesia: The tendency for one sense modality to evoke another His apparent inability to forget, and his synesthesia, caused great complications and struggle for him + Wilding and Valentine (1994) 5 Naturals vs. Strategists Naturals Strategists Innately gifted Highly practiced in certain mnemonic techniques Possess a close relative who exhibits a comparable level of memory ability Tested both kinds of mnemonists at the World Memory Championships on two types of tasks: Strategic Tasks e.g. -

ED 273 391 AUTHOR TITLE Metamemorial Knowledge, M-Space, and Working Memory PUB DATE Apr 86 NOTE 22P.; Paper Presented at the An

ED 273 391 PE 016 050 AUTHOR Ledger, George W.; Mca,ris, Kevin K. TITLE Metamemorial Knowledge, M-space, and Working Memory Performance in Fourth Graders. PUB DATE Apr 86 NOTE 22p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (67th, San Francisco, CA, April 16-20, 1986). PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) -- Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Elementary School Students; Grade 4; Intermediate Grades; *Memory; *Metacognition; *Predictor Variables IDENTIFIERS *Memory Span; *Metamemorial Knowledge ABSTRACT Three groups of fourth graders who differed on a metamemory pre-test were compared on five working memory tasks to explore the relationship between metamemorial knowledge, total processing space (M-space) and working memory span performance. Children in each group received three versions of each task on concurrent days. It was hypothesized that the group highest in metamemorial knowledge would score highest on the five working memory tasks. Results indicated that metamemory performance consistently predicted performance on the memory span measures. Three of the memory span measures showed a significant between-group effect on metamemory, while the remaining two evidenced strong trends in that direction. Analysis of repeated measures revealed no significant trials effects, indicating that no improvement in performance occurred across repeated presentations of the tasks. Implications for a metacognitive explanation of working memory processes and educational implications are discussed. (Author/RH) *******************************************i**************w*u********** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** DRAFT COPY FOR CRITIQUE SESSION George W. Ledger American Educational Research Association and April, 1986 - San Francisco Kevin K. -

Disordered Memory Awareness: Recollective Confabulation in Two Cases of Persistent Déj`A Vecu

Neuropsychologia 43 (2005) 1362–1378 Disordered memory awareness: recollective confabulation in two cases of persistent dej´ a` vecu Christopher J.A. Moulin a,b,∗, Martin A. Conway b, Rebecca G. Thompson a, Niamh James a, Roy W. Jones a a The Research Institute for the Care of the Elderly, St. Martin’s Hospital, UK b Institute of Psychological Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK Received 7 April 2004; received in revised form 10 December 2004; accepted 16 December 2004 Available online 11 March 2005 Abstract We describe two cases of false recognition in patients with dementia and diffuse temporal lobe pathology who report their memory difficulty as being one of persistent dej´ a` vecu—the sensation that they have lived through the present moment before. On a number of recognition tasks, the patients were found to have high levels of false positives. They also made a large number of guess responses but otherwise appeared metacognitively intact. Informal reports suggested that the episodes of dej´ a` vecu were characterised by sensations similar to those present when the past is recollectively experienced in normal remembering. Two further experiments found that both patients had high levels of recollective experience for items they falsely recognized. Most strikingly, they were likely to recollectively experience incorrectly recognised low frequency words, suggesting that their false recognition was not driven by familiarity processes or vague sensations of having encountered events and stimuli before. Importantly, both patients made reasonable justifications for their false recognitions both in the experiments and in their everyday lives and these we term ‘recollective confabulation’. -

Effectiveness of Method of Loci on Short-Term and Long-Term Memory

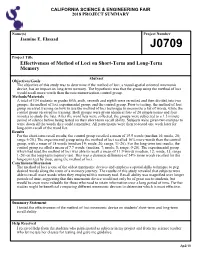

CALIFORNIA SCIENCE & ENGINEERING FAIR 2018 PROJECT SUMMARY Name(s) Project Number Jasmine E. Elasaad J0709 Project Title Effectiveness of Method of Loci on Short-Term and Long-Term Memory Abstract Objectives/Goals The objective of this study was to determine if the method of loci, a visual-spatial oriented mnemonic device, has an impact on long-term memory. The hypothesis was that the group using the method of loci would recall more words than the rote memorization control group. Methods/Materials A total of 134 students in grades fifth, sixth, seventh and eighth were recruited and then divided into two groups: the method of loci experimental group; and the control group. Prior to testing, the method of loci group received training on how to use the method of loci technique to memorize a list of words, while the control group received no training. Both groups were given identical lists of 20 simple nouns and four minutes to study the lists. After the word lists were collected, the groups were subjected to a 1.5 minute period of silence before being tested on their short-term recall ability. Subjects were given two minutes to write down all the words they could remember. All participants were then re-tested one week later for long-term recall of the word list. Results For the short-term recall results, the control group recalled a mean of 15.5 words (median 16; mode, 20; range 6-20.) The experimental group using the method of loci recalled 16% more words than the control group, with a mean of 18 words (median 19; mode, 20; range, 11-20). -

The Method of Loci in Virtual Reality: Explicit Binding of Objects to Spatial Contexts Enhances Subsequent Memory Recall

Journal of Cognitive Enhancement https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-019-00141-8 ORIGINAL RESEARCH The Method of Loci in Virtual Reality: Explicit Binding of Objects to Spatial Contexts Enhances Subsequent Memory Recall Nicco Reggente1 & Joey K. Y. Essoe1 & Hera Younji Baek1 & Jesse Rissman1,2 Received: 7 January 2019 /Accepted: 7 June 2019 # Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Abstract The method of loci (MoL) is a well-known mnemonic technique in which visuospatial spatial environments are used to scaffold the memorization of non-spatial information. We developed a novel virtual reality-based implementation of the MoL in which participants used three unique virtual environments to serve as their “memory palaces.” In each world, participants were presented with a sequence of 15 3D objects that appeared in front of their avatar for 20 s each. The experimental group (N = 30) was given the ability to click on each object to lock it in place, whereas the control group (N = 30) was not afforded this functionality. We found that despite matched engagement, exposure duration, and instructions emphasizing the efficacy of the mnemonic across groups, participants in the experimental group recalled 28% more objects. We also observed a strong relation- ship between spatial memory for objects and landmarks in the environment and verbal recall strength. These results provide evidence for spatially mediated processes underlying the effectiveness of the MoL and contribute to theoretical models of memory that emphasize spatial encoding as the primary currency of mnemonic function. Keywords Memory enhancement . Method of loci . Virtual reality Introduction the MoL is a complicated, time-consuming mnemonic to imple- ment, but in fact, it is rather straightforward.