Armenian Genocide Ch3.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For More Information About the Venues and Times of the Worldwide

Commemorating the Centenary of the Armenian Genocide Worldwide Reading on 21st April, 2015 Events in: Appeal for a worldwide reading on April 21st 2015 ARGENTINA Asociación Cultural Armenia, Buenos Aires | ARMENIA 1st Armenian Literary Agency, ArtBridge Bookstore Café / The international literature festival berlin (ilb) and the Lepsiushaus Civilnet Online Television, Yerevan; The Armenian Literature Foundation, Yerevan; Marine Karoyan, Tekeian Art Center, Yerevan; Potsdam are calling for a worldwide reading on 21 April 2015 - the day that marks 100 years since the beginning of the Armenian Goethe-Institut Georgien, Yerevan; Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute, Tsitsernakaberd, Yerevan; Centre of Juridical-political Genocide. and cultural diplomacy NGO, Yerevan; DAAD Armenien, Cafesijan Center for the Arts, Yerevan; The Armenian Educational Several hundred Armenian intellectuals – poets, musicians, Foundation, Yerevan | AUSTRALIA Armenian Book Club Australia, Theme and Variations Studios, Sydney; Pen Melbourne, parliamentary representatives and members of the clergy – were Melbourne | Anna Pfeiffer, FREIRAD 105.9 (Radio), Innsbruck | Thorsten Baensch, Aïda Kazarian, Boulevard arrested in Constantinople (today Istanbul) on 24 April 1915, AUSTRIA BELGIUM and deported to the Turkish interior where most of them were Jamar 19, Brussels; Anita Bernacchia, Ioana Belu, Bookshop EuropaNova, Brussels | BOLIVIA Bolivian PEN Centre, Plaza Callejas, murdered. It was the start of a crime against humanity. The Santa Cruz | BRAZIL Sibila journal, Sao Paulo; Lenira Buscato, Bandeirantes School, Sao Paulo | BULGARIA Armenian General extermination of the Armenians during World War One was the first Benevolent Union (AGBU) Plovdiv Chapter, Bourgas; AGBU Plovdiv Chapter, Haskovo; AGBU Plovdiv Chapter, Rouse; AGBU systematically planned and executed genocide of modern times. More than a million Armenians in the Ottoman Empire died during Plovdiv Chapter, Sliven; AGBU Plovdiv Chapter, Veliko Tarnovo; AGBU Plovdiv Chapter, Varna; Eojeni Sakaz, St.Kliment Ohridski this genocidal campaign. -

Varujan Vosganian, the Book of Whispers

Varujan Vosganian, The Book of Whispers Chapters seven and eight Translation: Alistair Ian Blyth Seven ‘Do not harm their women,’ said Armen Garo. ‘And nor the children.’ One by one, all the members of the Special Mission gathered at the offices of the Djagadamard newspaper in Constantinople. They had been selected with care. The group had been whittled down to those who had taken part in such operations before, working either alone or in ambush parties. ‘I trust only a man who has killed before,’ Armen Garo had declared. They were given photographs of those they were to seek out, wherever they were hiding. Their hiding places might be anywhere, from Berlin or Rome to the steppes of Central Asia. Broad-shouldered, bull-necked Talaat Pasha, the Minister of the Interior, was a brawny man, whose head, with its square chin and jaws that could rip asunder, was more like an extension of his powerful chest. In the lower part of the photograph, his fists, twice the size of a normal man’s, betokened pugnacity. Beside him, fragile, her features delicate, his wife wore a white dress and a lace cap in the European style, so very different from the pasha’s fez. Then there was Enver, a short man made taller by his boot heels. He had haughty eyes and slender fingers that preened the points of his moustache. He was proud of his army commander’s braids, which, cascading luxuriantly from his shoulders and covering his narrow chest, sought to disguise the humble beginnings of a son whose mother, in order to raise him, had plied one of the most despised trades in all the Empire: she had washed the bodies of the dead. -

Balakian Finds His Place in Dual Cultural Identity

NOVEMBER 21, 2015 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXVI, NO. 19, Issue 4413 $ 2.00 NEWS INBRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 Philanthropist Pledges ADL, Tekeyan $1 million for Telethon YEREVAN — The Hayastan All-Armenian Fund Members announces that Russian-Armenian industrialist and benefactor Samvel Karapetyan has pledged to con- tribute $1 million to the fund’s upcoming Convene in Thanksgiving Day Telethon. The telethon’s primary goal this year is to raise funds for the construction of single-family homes Armenia for families in Nagorno Karabagh who have five or YEREVAN — On November 2, members more children and lack adequate housing. Thanks and leaders of the Armenian Democratic to Karapetyan’s donation, some 115 children and Liberal Party (ADL) from several countries their parents will be provided with comfortable, assembled at the entrance of Building No. fully furnished homes. 47 of Yerevan’s Republic Street (formerly “We are grateful to our friend Samvel known as Alaverdian Street) to attend the Karapetyan, who for years has generously support- dedication of the ADL premises. ed our projects,” said Ara Vardanyan, executive The building, which houses the offices of director of the Hayastan All-Armenian Fund, and the ADL-Armenia, the editorial offices of added, “I’m confident that many of our compatriots Azg newspaper, the library, and the meeting will follow in his footsteps.” halls, has been fully renovated and refur- The telethon will air for 12 hours on bished by ADL friend and well-known phil- Thanksgiving Day, November 26, beginning at 10 anthropist from New Jersey, Nazar a.m. -

Genocidio Armeno”, E Non Solo

A proposito del “genocidio armeno”, e non solo Armeni scortati verso la prigione di Mezireh dai soldati ottomani, aprile 1915 Una risoluzione del Bundestag, intitolata “Memoria e commemorazione del genocidio degli armeni e di altre minoranze cristiane 101 anni fa”, definisce “genocidio”la strage di 1.5 milioni di armeni compiuta dai turchi ottomani tra il 1915 e il 1916. La mozione, presentata da Cdu, Spd e dai Verdi è stata approvata il 2 giugno con solo un voto contrario e un astenuto. Immediata la reazione del presidente Recep Tayyip Erdoğan: “Questa decisione avrà un impatto molto serio sulle relazioni tra la Turchia e la Germania”. Il richiamo dell’ambasciatore è solo “il primo passo”. Venti Paesi, tra i quali Italia, Francia e Russia hanno già riconosciuto ufficialmente lo status di genocidio al massacro degli armeni. L’anno scorso Papa Francesco definì gli eventi dell’epoca “il primo genocidio del Ventesimo secolo”. In quell’occasione, Franco Cardini scrisse per ytali. (26 aprile 2016) un lungo articolo sulla vicenda armena, che riproponiamo. Il termine “genocidio”, usato da papa Francesco durante l’Angelus della domenica in Albis (12 aprile 2015) per indicare la tragedia del popolo armeno nella penisola anatolica dell’inizio della quale quest’anno ricorre il formale centenario, ha scatenato involontariamente un vero e proprio uragano diplomatico. //https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gR-ds-QU8jk La repubblica turca ha sempre rifiutato che una tale responsabilità vada ascritta al paese, anche se – giova ricordarlo – fu proprio il governo turco uscito dalla bufera della prima guerra mondiale che, nel 1919, dispose la celebrazione di un processo per crimini di guerra contro i responsabili principali di quella catena di eccidi che aveva avuto il suo acme tra ’15 e ’17 e la loro condanna a morte (peraltro mai eseguita in quanto gli imputati erano contumaci). -

THE GREAT WAR and the TRAGEDY of ANATOLIA ATATURK SUPREME COUNCIL for CULTURE, LANGUAGE and HISTORY PUBLICATIONS of TURKISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY Serial XVI - No

THE GREAT WAR AND THE TRAGEDY OF ANATOLIA ATATURK SUPREME COUNCIL FOR CULTURE, LANGUAGE AND HISTORY PUBLICATIONS OF TURKISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY Serial XVI - No. 88 THE GREAT WAR AND THE TRAGEDY OF ANATOLIA (TURKS AND ARMENIANS IN THE MAELSTROM OF MAJOR POWERS) SALAHi SONYEL TURKISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRINTING HOUSE - ANKARA 2000 CONTENTS Sonyel, Salahi Abbreviations....................................................................................................................... VII The great war and the tragedy of Anatolia (Turks and Note on the Turkish Alphabet and Names.................................................................. VIII Armenians in the maelstrom of major powers) / Salahi Son Preface.................................................................................................................................... IX yel.- Ankara: Turkish Historical Society, 2000. x, 221s.; 24cm.~( Atattirk Supreme Council for Culture, Introduction.............................................................................................................................1 Language and History Publications of Turkish Historical Chapter 1 - Genesis of the 'Eastern Q uestion'................................................................ 14 Society; Serial VII - No. 189) Turco- Russian war of 1877-78......................................................................... 14 Bibliyografya ve indeks var. The Congress of B erlin....................................................................................... 17 ISBN 975 - 16 -

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan a Dissertation Submitted

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: David Alexander Rahbee, Chair JoAnn Taricani Timothy Salzman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2016 Tigran Arakelyan University of Washington Abstract Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. David Alexander Rahbee School of Music The goal of this dissertation is to make available all relevant information about orchestral music by Armenian composers—including composers of Armenian descent—as well as the history pertaining to these composers and their works. This dissertation will serve as a unifying element in bringing the Armenians in the diaspora and in the homeland together through the power of music. The information collected for each piece includes instrumentation, duration, publisher information, and other details. This research will be beneficial for music students, conductors, orchestra managers, festival organizers, cultural event planning and those studying the influences of Armenian folk music in orchestral writing. It is especially intended to be useful in searching for music by Armenian composers for thematic and cultural programing, as it should aid in the acquisition of parts from publishers. In the early part of the 20th century, Armenian people were oppressed by the Ottoman government and a mass genocide against Armenians occurred. Many Armenians fled -

Road from Home to America, Middle East and Diaspora, About Being Armenian Genocide Female Survivor

www.ccsenet.org/ies International Education Studies Vol. 4, No. 3; August 2011 Roots and Routes: Road from Home to America, Middle East and Diaspora, about Being Armenian Genocide Female Survivor Ani Derderian Aghajanian Washington State University E-mail: [email protected] Received: February 11, 2011 Accepted: February 28, 2011 doi:10.5539/ies.v4n3p66 Abstract Adolf Hitler, on August 22, 1939 stated, “I have given orders to my Death Units to exterminate without mercy or pity men, women, and children belonging to the Polish-speaking race. It is only in this manner that we can acquire the vital territory which we need. After all, who remembers today the extermination of the Armenians?” (Kherdian, 1979). Armenia is a land which has been ravaged by war on far too many occasions. Other nations keep turning it into a battlefield and tearing it apart. Armenian people have survived for many generations and their stories are told and retold during the hard winters. Armenians’ survived just as Armenia and Armenian culture have survived (Downing, 1972). Therefore, diverse life experience, traditions, histories, values, world views, and perspectives of the diverse cultural groups make up a society and preserve culture (Mendoza and Reese, 2001). In this study, two Armenian books “The Road from Home” and “The Knock at the Door” were analyzed. These books are organized as personal stories and experiences about Armenian female genocide survivors and are supplemented by background information on Armenian people before and after the genocide of their culture, including a brief history, discussion of traditions, recipes, music and religion. -

Adana, Massacre In, 57–59 Alice in Hungerland, 143 American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, 139, 140 American Commit

the genocide of the armenians • 191 INDEX Adana, massacre in, 57–59 reasons for, 81–82; survivors, 83–84; Alice in Hungerland, 143 Turkish explanations for, 85, 87, 92; American Committee for women and children, abuse of, 98–106; Armenian and Syrian Relief, 139, 140 World War I and, 87, 89, 90, 91 American Committee for Relief in the Near East Armenian Genocide: News Accounts from the (ACRNE), 139, 141 American Press: 1915–1922 (Zakarian), 76 American Red Cross, 45 Armenian Revolutionary Federation American Relief Administration (ARA), 160 (Dashnakstutiun), 31, 42–43, 48–50, 51, 59 Aroosian, Arax, 4 Anatolia, 85 Assyrians, treatment of, 110 Andreasian, Dikran, 125–126 Axis Rule in Occupied Europe (Lemkin), 186 Ararat, Mt., 12 Arendt, Hannah, 175 Arlen, Michael J., 4, 5, 181–182 Balakian, Krikoris, 92–93 Argentina, the Disappeared in, 12 Balakian, Peter, 3–4, 12, 31–33, 42–43 Armenakan Party, 31 Balkan League, 65 Armenia, Balkans, fighting in the, 28–29 history of, 23–24; Bank Ottoman, 48–49, 50 map of historic, 22; Republic of, 147–148, 162–164 Barton, Clara, 45 Barton, James L., 139, 140 Armenian(s), fighting in the Balkans and position of, 28–30; Berlin, treaty of, 28–29, 31, 171 identity, 10–13; Bey, Essad, 73 organizing for change following the Treaty of Berlin, 31–33; Bitlis, 84 views of the Great Powers toward, 23–24; Black Dog of Fate (Balakian), 3, 12 we (Armenians) versus they (Turks), 68–70 Bloody News from My Friend (Siamanto), 58 Armenian Genocide, choices and, 113–144; Boettrich, Lieutenant Colonel, 94 denial of, 174–179; -

1 1915 IS GENOCIDE, a CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY We Came Here Once More to Commemorate the Prominent Members of the Arme

1915 IS GENOCIDE, A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY We came here once more to commemorate the prominent members of the Armenian community of Istanbul who were arrested on Saturday, 24th April 1915. This old building, which serves now as the Turkish Islamic Arts Museum, is in fact the Ibrahim Pasha Palace which was used for long years as a prison. This is the place where those arrested during the 24th April 1915 round‐ups were kept before being sent to Haydarpasha train station to be taken into the inlands of Anadolia and from there to their death. Today the websites of government departments, of the General Staff and other organisations loyal to the state tell a different story with exactly the same wording as if all were written by the same person. They say those arrested on the 24th of April were Armenian “Komitacis”, i.e. outlaws who were engaged in subversive activities against the state. They all lie. The vast majority of those who were arrested in Istanbul were the most brilliant leaders of the Armenian community, politicians, writers, poets, journalists, doctors, scientists. Among them was a monumental figure, Gomidas Vartabed, who collected and scored thousands of Turkish, Kurdish and Armenian folk songs travelling throughout Anatolia village by village. Let’s remember some of these great Armenian intellectuals: Armen Dorian – A graduate of Sorbonne university, poet, 23 years old. Yervant Chavoushian – University professor, writer journalist Roupen Zartarian – Poet, writer, teacher and translator. Diran Kelekian –Professor of Political Sciences, writer, publisher, translator, chief editor of the Turkish daily Sabah. Yervant Sırmakeshanlian – pedagogue, translator, journalist. -

Ani Kolangian

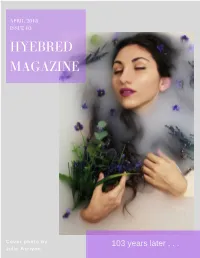

APRIL 2018 ISSUE 03 HYEBRED MAGAZINE Cover photo by 103 years later . Julie Asriyan Forget-Me-Not Issue 03 Prose Music Anaïs Chagankerian . 6 Brenna Sahatjian . 13 Lizzie Vartanian Collier . 20 Ani Kalayjian . 34 Armen Bacon . .38 Mary Kouyoumdjian . 36 Poetry Art & Photography Ani Chivchyan . 3 Julie Asriyan . 10 Ronald Dzerigian . 14 Ani Iskandaryan . 18 Nora Boghossian . .16 Susan Kricorian . 28 Rita Tanya . .31 Ani Kolangian . .32 John Danho . .49 Nicole Burmeister . .52 A NOTE OF GRATITUDE Dear Faithful Reader, This issue is dedicated to our Armenian ancestors. May their stories never cease to be told or forgotten. As April is Genocide Awareness Month, the theme for this issue is fittingly 'Forget-Me-Not.' It has been 103 years since the Armenian Genocide, a time in Armenian history that still hurts and haunts. HyeBred Magazine represents the vitality and success of the Armenian people; it showcases how far we have come. Thank you to our wonderfully talented contributors. Your enthusiastic collaboration enhances each successive publication. Thank you, faithful reader, as your support is what keeps this magazine alive and well. Շնորհակալություն. The HyeBred Team Ani Chi vchyan Self Love don't let yourself get in the way of yourself the same way you can harm yourself, adding salt to those wounds and grow only in sorrow and grief only to become tired of yourself you have the power to heal and love admire celebrate your existence in this world water those roots and make something beautiful out of you H Y E B R E D I S S U E 0 3 | 3 By -

JSAS 21-Russell Article-Final.Pdf (448.3Kb)

The Bells: From Poe to Sardarapat The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Russell, James R. 2012. The bells: From Poe to Sardarapat. Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies 21:1-42. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10880591 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies 21 (2012), pp. 1- THE BELLS: FROM POE TO SARDARAPAT JAMES R. RUSSELL Was it a dark and stormy night? No, but at least it was on a crisp and sere one, in autumn, and the scene is an old wooden house shaded by huge, gaunt trees. The nervous, overweight boy from the big city was uncomfortable with his four suburban cousins, with their healthy, athletic roughhousing and clean, wholesome, all-American good looks: their parents had not circumcised them and had rejected the antique language, the prophetic faith, and the tribal old- new land. But in the living room the Franklin stove crackled, all was bright and warm, and his aunt and uncle had put on a newly pressed record, “All The News That’s Fit to Sing” (Elektra Records, 1964)— a topical irony, since The New York Times boasted then, and still does, that it offers all the news fit to print. -

Actor's Actor Charles Aznavour to Be Honored in NYC By

APRIL 2, 2011 MirTHE rARoMENr IAN -Spe ctator Volume LXXXI, NO. 38, Issue 4182 $ 2.00 NEWS IN BRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Azeris Launch Attacks STEPANAKERT (PanARMENIAN.Net) — Between Charles Aznavour to Be March 20 and 26, Azerbaijan violated the ceasefire regime at the Karabagh conflict zone. According to updated data of the Nagorno Karabagh Honored in NYC by FAR Defense Army, Azerbaijan violated the ceasefire 250 times during the week, firing 1,800 shots. The NKR Army press service stressed that in French ambassador-at large to Armenia. addition to typical weapons, the Azerbaijani forces By Florence Avakian The gala tribute will take place at New used AGA grenade launchers against the Karabagh York’s elegant Cipriani Wall Street venue, positions in Martuni on March 24 and 25. with a reception starting at 7 p.m., and din - NEW YORK — Mark Friday, May 20 on ner with a special program at 8 p.m. your calendars. The date marks an event Introducing Aznavour will be singer Liza Davutoglu: 2015 Will sponsored by the Fund for Armenian Minnelli, and master of ceremonies will be Relief (FAR) that celebrates both the actor Eric Bogosian, both of whom are on Be Dedicated to 20th anniversary of Armenia’s indepen - the “Honorary Committee of Tribute to ‘Armenian Issue’ dence, as well as one of the world’s great - Aznavour.” Other known personalities on est singers, showmen, songwriters and the committee include Sir Elton John, LONDON (Arminfo) — The year of 2015 will be ded - philanthropists, Charles Aznavour.