Proposed Mid-Term Review Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HSRC CWC.Indb

www.hsrcpress.ac.za from CRISIS! download Free WHAT CRISIS? THE MULTIPLE DIMENSIONS OF THE ZIMBABWEAN CRISIS Edited by Sarah Chiumbu and Muchaparara Musemwa Published by HSRC Press Private Bag X9182, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa www.hsrcpress.ac.za First published 2012 ISBN (soft cover): 978-0-7969-2383-7 ISBN (pdf): 978-0-7969-2384-4 ISBN (e-pub): 978-0-7969-2385-1 © 2012 Human Sciences Research Council The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Human Sciences Research Council (‘the Council’) or indicate that the Council endorses the views of the authors. In quoting from this publication, www.hsrcpress.ac.za readers are advised to attribute the source of the information to the individual author concerned and not to the Council. from Chapter 1 is a revised version of a paper originally published in the Journal of Developing Societies 26(2): 165–206, copyright © Sage Publications (all rights reserved) and is reproduced here with the permission of the copyright holders and the publishers, Sage Publications India Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi. download Free Chapter 2 is a revised version of a paper by Mukwedeya T (2011) originally published as ‘Zimbabwe’s saving grace: The role of remittances in household livelihood strategies in Glen Norah, Harare’ in the South African Review of Sociology 42(1): 116–130, copyright © South African Sociological Association reprinted by permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com on behalf of the South African Sociological Association. Chapter 4 is a revised version of a paper originally published in M Palmberg & R Primorac (eds) Skinning the Skunk: Facing Zimbabwean Futures (2005), copyright © the editors and the Nordic Africa Institute (NAI) and is reproduced here with the permission of the editors and the NAI. -

Zimbabwe Annual Budget Review for 2016 and the 2017 Outlook

ZIMBABWE ANNUAL BUDGET REVIEW FOR 2016 AND THE 2017 OUTLOOK Presented to the Parliament of Zimbabwe on Thursday, July 20, 2017 by The Hon. P. A. Chinamasa, M.P. Minister of Finance and Economic Development 1 1 2 FOREWORD In presenting the 2017 National Budget on 8 December 2016, I indicated the need to strengthen the outline of the Budget Statement presentation as an instrument of Budget accountability and fiscal transparency, in the process improving policy engagement and accessibility for a wider range of public and targeted audiences. Accordingly, I presented a streamlined Budget Statement, and advised that extensive economic review material, which historically was presented as part of the National Budget Statement, would now be provided through a new publication called the Annual Budget Review. I am, therefore, pleased to unveil and Table the first Annual Budget Review, beginning with Fiscal Year 2016. This reports on revenue and expenditure outturn for the full fiscal year, 2016. Furthermore, the Annual Budget Review also allows opportunity for reporting on other recent macro-economic developments and the outlook for 2017. As I indicated to Parliament in December 2016, the issuance of the Annual Budget Review, therefore, makes the issuance of the Mid-Term Fiscal Policy Review no longer necessary, save for exceptional circumstances requiring Supplementary Budget proposals. 3 Treasury will, however, continue to provide Quarterly Treasury Bulletins, capturing quarterly macro-economic and fiscal developments, in addition to the Consolidated Monthly Financial Statements published monthly in line with the Public Finance Management Act. This should avail the public with necessary information on relevant economic developments, that way enhancing and supporting their decision making processes, activities and engagement with Government on overall economic policy issues. -

LAN Installation Sites Coordinates

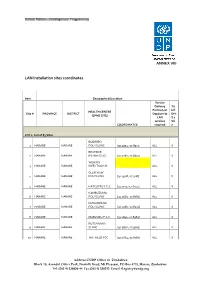

ANNEX VIII LAN Installation sites coordinates Item Geographical/Location Service Delivery Tic Points (List k if HEALTH CENTRE Site # PROVINCE DISTRICT Dept/umits DHI (EPMS SITE) LAN S 2 services Sit COORDINATES required e LOT 1: List of 83 Sites BUDIRIRO 1 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9354,-17.8912] ALL X BEATRICE 2 HARARE HARARE RD.INFECTIO [31.0282,-17.8601] ALL X WILKINS 3 HARARE HARARE INFECTIOUS H ALL X GLEN VIEW 4 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9508,-17.908] ALL X 5 HARARE HARARE HATCLIFFE P.C.C. [31.1075,-17.6974] ALL X KAMBUZUMA 6 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9683,-17.8581] ALL X KUWADZANA 7 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9285,-17.8323] ALL X 8 HARARE HARARE MABVUKU P.C.C. [31.1841,-17.8389] ALL X RUTSANANA 9 HARARE HARARE CLINIC [30.9861,-17.9065] ALL X 10 HARARE HARARE HATFIELD PCC [31.0864,-17.8787] ALL X Address UNDP Office in Zimbabwe Block 10, Arundel Office Park, Norfolk Road, Mt Pleasant, PO Box 4775, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: (263 4) 338836-44 Fax:(263 4) 338292 Email: [email protected] NEWLANDS 11 HARARE HARARE CLINIC ALL X SEKE SOUTH 12 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0763,-18.0314] ALL X SEKE NORTH 13 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0943,-18.0152] ALL X 14 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ST.MARYS CLINIC [31.0427,-17.9947] ALL X 15 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ZENGEZA CLINIC [31.0582,-18.0066] ALL X CHITUNGWIZA CENTRAL 16 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA HOSPITAL [31.0628,-18.0176] ALL X HARARE CENTRAL 17 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [31.0128,-17.8609] ALL X PARIRENYATWA CENTRAL 18 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [30.0433,-17.8122] ALL X MURAMBINDA [31.65555953980,- 19 MANICALAND -

A Biographical Study of Bishop Ralph Edward Dodge 1907 – 2008

ABSTRACT Toward a New Church in a New Africa: A Biographical Study of Bishop Ralph Edward Dodge 1907 – 2008 This biography of a Methodist Bishop, Ralph Edward Dodge is an extensive look into how, as a missionary, mission board executive, and bishop, Dodge applied principles of indigenization he embraced as a young man preparing for missionary work to the complexities of ministry in Southern Africa when empires were withdrawing and new nations were forming. Written by an African, the dissertation examines Dodge’s impact upon the several countries in which he was involved as a churchman ‒ countries that would soon move from imperial subjugation to independence. Ralph Edward Dodge (1907–2008) was an American missionary and Bishop of the Methodist Church and United Methodist Church. He was born in Iowa and went to Africa in 1936 at age 29. He began his missionary career in the Portuguese colony of Angola. Except for four years during World War II, he would serve there until 1950. During the war, he continued his postgraduate work, obtaining two more degrees, including a PhD. Afterwards, Dodge and his family returned to Africa. In 1950, he was asked to serve as Executive Secretary for Africa and Europe at the Methodist Church’s Board of Missions in New York. Six years later, the Reverend Doctor Dodge would return to Africa as Bishop Dodge, the first Methodist Bishop elected by the Africa Central Conference, and the only American. His Episcopal Area included the colonial territories of Angola, Mozambique, and Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). When his twelve-year term was ended, he was elected “Bishop for Life.” Bishop Dodge remained in Africa until his “retirement” in 1968. -

Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment Project Baseline Assessment Report

20 16 Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment Project Baseline Assessment Report '' CARG members in Chipinge meet for drug refill in the community. Photo Credits// FHI 360 Zimbabwe'' This study is made possible through the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID.) The contents are the sole responsibility of the Zimbabwe HIV care and Treatment (ZHCT) Project and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. FOREWORD The Government of Zimbabwe (GoZ) through the Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC) is committed to strengthening the linkages between public health facilities and communities for HIV prevention, care and treatment services provision in Zimbabwe. The Ministry acknowledges the complementary efforts of non-governmental organisations in consolidating and scaling up community based initiatives towards achieving the UNAIDS ‘90-90-90’ targets aimed at ending AIDS by 2030. The contribution by Family Health International (FHI360) through the Zimbabwe HIV Care and Treatment (ZHCT) project aimed at increasing the availability and quality of care and treatment services for persons living with HIV (PLHIV), primarily through community based interventions is therefore, lauded and acknowledged by the Ministry. As part of the multi-sectoral response led by the Government of Zimbabwe (GOZ), we believe the input of the ZHCT project will strengthen community-based service delivery, an integral part of the response to HIV. The Ministry of Health and Child Care however, has noted the paucity of data on the cascade of HIV treatment and care services provided at community level and the ZHCT baseline and mapping assessment provides valuable baseline information which will be used to measure progress in this regard. -

Zimbabwe Nutrition Cluster

W Zimbabwe Nutrition Cluster https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/Zimbabwe Zimbabwe Nutrition Cluster monthly meeting 27 March 2020, 09:30 to 12:00, Zoom Online Meeting Meeting minutes Chair: Nutrition Cluster Coordinator, Agnes Kihamia, Nutrition Cluster Note taker: IMO, Nakai Munikwa, Nutrition Cluster Agenda 1. Welcome and introductions 2. Nutrition Cluster Contingency Plan in the context of COVID – 19 by NCC/MoHCC 3. Updates on SC and OTP admissions, Screening for acute malnutrition activities in 25 priority districts by MoHCC 4. Nutrition Cluster and Food Security cluster linkage and partners responsibilities by UNICEF 5. Pellagra updates 6. Update from partners 7. AoB Action point Focal point/agency Timeline Status [from the previous meeting minutes] [from the previous [from the previous [Status update, for example: completed, ongoing, meeting minutes] meeting minutes] pending. You may want to specify here why the action point was not completed] Share protocol for MAM treatment with Sector Partners MoHCC - Nyadzayo 1/31/2020 Done Cluster Coordinator Zimbabwe Nutrition Cluster monthly meeting, Agnes Kihamia 27 March 2020, Meeting minutes [email protected] , +263775920472 Page 1 W Zimbabwe Nutrition Cluster https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/Zimbabwe Main Agenda Items Discussion point/cluster partner Focal Action points Timeline point/agency Nutrition Cluster Contingency Plan in the context of COVID – 19 by Follow up on nutrition programming in COVID-19 era: NCC and Updates by NCC/MoHCC: 1) How will CHWs be equipped to carry on with their MoHCC next work. Protective gear for frontline workers could be meeting. a contingency plan to ensure that they are protected. -

Manicaland-Province

School Level Province District School Name School Address Secondary Manicaland Buhera BANGURE ZVAVAHERA VILLAGE WARD 19 CHIEF NYASHANU BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera BETERA HEADMAN BETERA CHIEF NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera BHEGEDHE BHEGEDHE VILLAGE CHIEF CHAMUTSA Secondary Manicaland Buhera BIKA KWARAMBA VILLAGE WARD 16 CHIEF NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera BUHERA GAVA VILLAGE WARD 5 CHIEF MAKUMBE BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHABATA MUVANGIRWA VILLAGE WARD 29 Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHANGAMIRE MATSVAI VILLAGE WARD 32 NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHAPANDUKA CHAPANDUKA VILLAGE CHIEF NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHAPWANYA CHAPWANYA HIGH SCHOOL WARD 2 BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHAWATAMA CHAWATAMA VILLAGE WARD 31 CHIEF MAKUMBE Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHIMBUDZI MATASVA VILLAGE WARD 32 CHIEF NYASHANU CHINHUWO VILLAGE CHIWENGA TOWNSHIP CHIEF Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHINHUWO NYASHANU Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHIROZVA CHIROZVA VILLAGE Secondary Manicaland Buhera CHIURWI CMAKUVISE VILLAGE WARD 32 Secondary Manicaland Buhera DEVULI NENDANDA VILLAGE CHIEF CHAMUTSA WARD 33 Secondary Manicaland Buhera GOSHO SOJINI VILLAGE WARD 5 CHIEF MAKUMBE Secondary Manicaland Buhera GOTORA GOTORA VILLAGE WARD 22 CHIEF NYASHANU BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera GUNDE MABARA VILLAGE WARD 9 CHIEF CHITSUNGE BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera GUNURA CHIEF CHAMUTSA NEMUPANDA VILLAGE WARD 30 BUHERA Secondary Manicaland Buhera GWEBU GWEBU SECONDARY GWEBU VILLAGE Secondary Manicaland Buhera HANDE KARIMBA VILLAGE -

Zimbabwe Nutrition Cluster Monthly Meeting 08 May 2020, 10:00 to 12:00, Zoom Online Meeting

W Zimbabwe Nutrition Cluster https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/Zimbabwe Zimbabwe Nutrition Cluster monthly meeting 08 May 2020, 10:00 to 12:00, Zoom Online Meeting Meeting minutes Chair: Nutrition Cluster Coordinator, Agnes Kihamia, Nutrition Cluster Note taker: IMO, Nakai Munikwa, Nutrition Cluster Agenda 1. Welcome and Introduction 5 mins by NCC 2. Review of the action points 10 mins by NCC 3. Cluster update, HRP performance and gap update 15 mins by IMO and NCC 4. Presentation on draft guidelines on Nutrition Support in Critically ill COVID-19 patients (DAZ) 25 mins by MoHCC 5. Update on AAP from partners and MoHCC provinces 30 mins 6. Key updates (achievement and challenges) from partners and MoHCC provinces 30 mins 7. AOB 5 mins. Action points from previous meetings Discussion point/cluster partner Action points Focal point/agency Status Comments Report has been reviewed by MoHCC. Further analysis has been done. Restructuring is also being done. Report on Pellagra to be shared by mid- Pellagra update; Availability of the Nicotinamide so far, April. Draft already available. the quantification was done for nicotinamide of about 6000 1 Mr. Nyadzayo in-progress supplements. A letter has been drafted Cluster Coordinator Zimbabwe Nutrition Cluster monthly meeting, Agnes Kihamia 27 March 2020, Meeting minutes [email protected] , +263775920472 Page 1 W Zimbabwe Nutrition Cluster https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/Zimbabwe which is with the PS for the procurement that will need concurrency with UNICEF. The initial group that was working on pellagra to concentrate on developing the report. Comments on Pellagra report Committee on Pellagra to meet once the are expected from WHO, UNICEF and report is in a better state. -

Urban Solid Waste Management in Zimbabwe

European Journal of Sustainable Development (2013), 2, 1, 67-98 ISSN: 2239-5938 Confronting the Reckless Gambling With People’s Health and Lives: Urban Solid Waste Management in Zimbabwe By 1Enock C.Makwara and 1Snodia Magudu Abstract Litter has become a common sight along high ways and in many urban and peri-urban communities in Zimbabwe. In spite of the numerous clean-up and anti-litter campaigns that have been initiated by different individuals and organizations coupled with the tremendous effort that has been put in making the public aware of the disadvantages associated with littering, endemic and insistent filth engulfs Zimbabwe as people continue to litter. Zimbabwe’s waste management has virtually collapsed, triggering chaotic and rampant waste dumping, putting the health of residents at great risk. The prevalence of various forms of litter in these communities has been fuelled by a consumerist corporate and social culture where a lot of packaged foodstuffs are manufactured to be consumed on the run. Inefficient collection mechanisms by municipalities and lack of ‘separate at source’ models have led to adverse effects on our ecosystem and the environment. Litter has primary and secondary effects on the environment and the community. The corporate world is affected by disease outbreaks as employees are either directly or indirectly affected. Considering that most industries are located within the vicinity of high density areas, their industrial waste management systems are also a cause for concern. Considering all the above mentioned factors, the paper examines ways and means of effectively managing waste in Zimbabwe’s urban areas to reduce the exposure of people and the environment to waste hazards. -

List of Registration Centers by Province Contents

This document was downloaded from www.zimelection.com. The information may have been updated this this file was download. Visit our website to get up to date information. Like our Facebook page to get updates: https://www.facebook.com/ZimbabweElection2018. List of Registration Centers by Province Last Updated: 10 May 2018 Contents Bulawayo Metropolitan ................................................................................................................................ 1 Harare Metropolitan ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Manicaland.................................................................................................................................................... 1 Mashonaland Central .................................................................................................................................... 2 Mashonaland East ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Mashonaland West ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Masvingo ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Midlands ...................................................................................................................................................... -

ZIMBABWEAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority

ZIMBABWEAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority Vol. XCVIII, No. 49 22nd MAY, 2020 Price RTGS$20,00 General Notice 863 of 2020. CUSTOMS AND EXCISE ACT [CHAPTER 23:02] Zimbabwe Revenue Authority: Notice of Intention to sell Unclaimed Vehicles NOTICE is hereby given in terms of section 39(2) of the Customs and Excise Act [Chapter 23:02], that the following vehicles will be dealt with in terms of section 39(3) and 39(4) of the Customs and Excise Act [Chapter 23:02] if not claimed within 30 days of the publication of this notice. The owners of these vehicles are unknown and the goods will be sold if not claimed within thirty days of the publication of this notice. The vehicles are accident damaged and were abandoned at Vehicle Inspection Depots in Gwanda and Bulawayo. The vehicles are being held at Manica Container Depot, Stand No. 3041, Institute Avenue, Raylton, Bulawayo, and Vehicle Inspection Depot premises in Gwanda. MS. F. MAZANI, 22-5-2020. Commissioner-General Zimbabwe Revenue Authority. Schedule UNCLAIMED VEHICLES DETENTION DATE OF REG ENGINE CHASSIS No MAKE STATUS YEAR LOCATION DETAILS DETENTION NUMBER NUMBER NUMBER Manica TOYOTA Accident Container 1 N/S 023183 14/12/2011 REG# B960ACT UNKNOWN MX75-0004189 Unknown CRESSIDA damaged Depot- Bulawayo HOMEMADE REG# LH- VID - 2 RIH 188365 14/10/2015 UNKNOWN NOT SEEN Unknown LIGHT TRAILER M588GP Gwanda TOYOTA PICK Accident VID - 3 RIH 188395 14/10/2015 REG# PHZ641GP 612160 5R2206954 Unknown UP Damaged Gwanda DATSUN REG# DR- Accident VID - 4 RIH 188394 14/10/2015 A09544 Unknown SEDAN -

2021 Zim Infrastructure Investment Programme.Pdf

1 1 DISTRIBUTED BY VERITAS e-mail: [email protected]; website: www.veritaszim.net Veritas makes every effort to ensure the provision of reliable information, but cannot take legal responsibility for information supplied. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 9 DRIVERS OF INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT . 12 CLIMATE CHANGE . 15 INFRASTRUCTURE DELIVERY UPDATE . 17 Projects Delivery Review . 19 2020 Infrastructure Investment Programme Update . 21 NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY (NDS1) 2021-2025 . 33 2021 INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT PROGRAMME . 35 Prioritation Framework . 36 ENERGY . 38 Sector Overview . 39 2021 Priority Interventions for the Energy Sector . 40 WATER SUPPLY AND SANITATION . 42 Sector Overview . 45 Dam Projects . 46 Urban Water and Sanitation . 48 Water Supply Schemes for Small Towns and Growth Points . 49 Rural WASH . 50 TRANSPORT . 51 Sector Overview . 52 Roads . 53 Rail Transport . 59 Airports . 60 Border Posts . 62 HOUSING DEVELOPMENT . 64 Policy Interventions . 65 Institutional Housing . 66 Social Housing . 68 Spatial Planning . 69 Civil Service Housing Fund . 70 DIGITAL ECONOMY . 70 Sector Overview . 71 2021 ICT Priority Interventions . 72 AGRICULTURE . 75 Irrigation Development . 76 HUMAN CAPITAL DEVELOPMENT AND WELL BEING . 80 Education . 80 Health . 82 Social Services . 86 TRANSFERS TO PROVINCIAL COUNCILS & LOCAL AUTHORITIES . 87 PROCUREMENT . 89 MONITORING AND REPORTING ON PROGRESS . 91 3 FOREWORD Occurrences of epidemics, natural disasters and calamities are often unpredictable, with volatile impacts on economies and communities across the globe. The resultant after-shocks invariably undermine income and employment prospects, exacerbating inequalities, in particular for vulnerable groups within societies. The COVID 19 pandemic, whose effects and devastation have been felt across all parts of the world, have magnified pre-existing differences in economic and social conditions of the vulnerable citizenry.