Folklore of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Site Selection Document: Summary of the Scientific Case for Site Selection

West Coast of the Outer Hebrides Proposed Special Protection Area (pSPA) No. UK9020319 SPA Site Selection Document: Summary of the scientific case for site selection Document version control Version and Amendments made and author Issued to date and date Version 1 Formal advice submitted to Marine Scotland on Marine draft SPA. Scotland Nigel Buxton & Greg Mudge 10/07/14 Version 2 Updated to reflect change in site status from draft Marine to proposed in preparation for possible formal Scotland consultation. 30/06/15 Shona Glen, Tim Walsh & Emma Philip Version 3 Updated with minor amendments to address Marine comments from Marine Scotland Science in Scotland preparation for the SPA stakeholder workshop. 23/02/16 Emma Philip Version 4 Revised format, using West Coast of Outer MPA Hebrides as a template, to address comments Project received at the SPA stakeholder workshop. Steering Emma Philip Group 07/04/16 Version 5 Text updated to reflect proposed level of detail for Marine final versions. Scotland Emma Philip 18/04/16 Version 6 Document updated to address requirements of Greg revised format agreed by Marine Scotland. Mudge Glen Tyler & Emma Philip 19/06/16 Version 7 Quality assured Emma Greg Mudge Philip 20/6/16 Version 8 Final draft for approval Andrew Emma Philip Bachell 22/06/16 Version 9 Final version for submission to Marine Scotland Marine Scotland 24/06/16 Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 2. Site summary ..................................................................................................... 2 3. Bird survey information .................................................................................... 5 4. Assessment against the UK SPA Selection Guidelines ................................. 7 5. Site status and boundary ................................................................................ 13 6. Information on qualifying species ................................................................. -

S. S. N. S. Norse and Gaelic Coastal Terminology in the Western Isles It

3 S. S. N. S. Norse and Gaelic Coastal Terminology in the Western Isles It is probably true to say that the most enduring aspect of Norse place-names in the Hebrides, if we expect settlement names, has been the toponymy of the sea coast. This is perhaps not surprising, when we consider the importance of the sea and the seashore in the economy of the islands throughout history. The interplay of agriculture and fishing has contributed in no small measure to the great variety of toponymic terms which are to be found in the islands. Moreover, the broken nature of the island coasts, and the variety of scenery which they afford, have ensured the survival of a great number of coastal terms, both in Gaelic and Norse. The purpose of this paper, then, is to examine these terms with a Norse content in the hope of assessing the importance of the two languages in the various islands concerned. The distribution of Norse names in the Hebrides has already attracted scholars like Oftedal and Nicolaisen, who have concen trated on establis'hed settlement names, such as the village names of Lewis (OftedaI1954) and the major Norse settlement elements (Nicolaisen, S.H.R. 1969). These studies, however, have limited themselves to settlement names, although both would recognise that the less important names also merit study in an intensive way. The field-work done by the Scottish Place Name Survey, and localised studies like those done by MacAulay (TGSI, 1972) have gone some way to rectifying this omission, but the amount of material available is enormous, and it may be some years yet before it is assembled in a form which can be of use to scholar ship. -

Last Children of the Gods

Last Children of The Gods Adventures in a fantastic world broken by the Gods By Xar [email protected] Version: alpha 9 Portals of Convenience Portals of Convenience 1 List of Tables 3 List of Figures 4 1 Childrens Stories 5 1.1 Core Mechanic ............................................... 5 1.2 Attributes.................................................. 6 1.3 Approaches................................................. 6 1.4 Drives.................................................... 7 1.5 Considerations ............................................... 8 2 A Saga of Heroes 9 2.1 Character Creation............................................. 9 2.2 Player Races ................................................ 9 2.3 Talents.................................................... 11 2.4 Class..................................................... 13 2.5 Secondary Characteristics......................................... 14 2.6 Bringing the character to life ....................................... 14 2.7 Considerations ............................................... 14 3 Grimoire 16 3.1 Defining Mages............................................... 16 3.2 The Shadow Weave............................................. 16 3.3 Elemental Magic .............................................. 16 3.4 Rune Magic................................................. 16 3.5 True Name Magic.............................................. 16 3.6 Blood Magic ................................................ 17 3.7 Folklore .................................................. -

The Misty Isle of Skye : Its Scenery, Its People, Its Story

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES c.'^.cjy- U^';' D Cfi < 2 H O THE MISTY ISLE OF SKYE ITS SCENERY, ITS PEOPLE, ITS STORY BY J. A. MACCULLOCH EDINBURGH AND LONDON OLIPHANT ANDERSON & FERRIER 1905 Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome, I would see them before I die ! But I'd rather not see any one of the three, 'Plan be exiled for ever from Skye ! " Lovest thou mountains great, Peaks to the clouds that soar, Corrie and fell where eagles dwell, And cataracts dash evermore? Lovest thou green grassy glades. By the sunshine sweetly kist, Murmuring waves, and echoing caves? Then go to the Isle of Mist." Sheriff Nicolson. DA 15 To MACLEOD OF MACLEOD, C.M.G. Dear MacLeod, It is fitting that I should dedicate this book to you. You have been interested in its making and in its publica- tion, and how fiattering that is to an author s vanity / And what chief is there who is so beloved of his clansmen all over the world as you, or whose fiame is such a household word in dear old Skye as is yours ? A book about Skye should recognise these things, and so I inscribe your name on this page. Your Sincere Friend, THE A UTHOR. 8G54S7 EXILED FROM SKYE. The sun shines on the ocean, And the heavens are bhie and high, But the clouds hang- grey and lowering O'er the misty Isle of Skye. I hear the blue-bird singing, And the starling's mellow cry, But t4eve the peewit's screaming In the distant Isle of Skye. -

Geomorphological Signature and Flow Dynamics of the Minch Palaeo-Ice Stream, NW Scotland

Geomorphological signature and flow dynamics of The Minch palaeo-ice stream, NW Scotland Tom Bradwell*1, Martyn Stoker1 & Rob Larter2 1 British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh, EH9 3LA, UK 2 British Antarctic Survey, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge, CB3 0ET, UK *corresponding author: email: [email protected] phone: 0131 6500284 fax: 0131 6681535 Abstract Large-scale streamlined glacial landforms are identified in 11 areas of NW Scotland, from the Isle of Skye in the south to the Butt of Lewis in the north. These ice-directional features occur in bedrock and superficial deposits, generally below 350 m above sea level, and where best developed have elongation ratios of >20:1. Sidescan sonar and multibeam echo-sounding data from The Minch show elongate streamlined ridges and grooves on the seabed, with elongation ratios of up to 70:1. These bedforms are interpreted as mega-scale glacial lineations. All the features identified formed beneath The Minch palaeo-ice stream which was c. 200 km long, up to 50 km wide and drained ~15,000 km2 of the NW sector of the last British-Irish Ice Sheet (Late Devensian Glaciation). Nine ice-stream tributaries and palaeo- onset zones are also identified, on the basis of geomorphological evidence. The spatial distribution and pattern of streamlined bedforms around The Minch has enabled the catchment, flow paths and basal shear stresses of the palaeo-ice stream and its tributaries to be tentatively reconstructed. Keywords: British-Irish Ice Sheet, Late Devensian, subglacial bedforms, palaeo-glaciology Introduction The palaeo-glaciology of the British-Irish Ice Sheet remains poorly understood despite a long history of glacial research in the UK. -

The Battle for Roineabhal

The Battle for Roineabhal Reflections on the successful campaign to prevent a superquarry at Lingerabay, Isle of Harris, and lessons for the Scottish planning system © Chris Tyler The Battle for Roineabhal: Reflections on the successful campaign to prevent a superquarry at Lingerabay, Isle of Harris and lessons for the Scottish planning system Researched and written by Michael Scott OBE and Dr Sarah Johnson on behalf of the LINK Quarry Group, led by Friends of the Earth Scotland, Ramblers’ Association Scotland, RSPB Scotland, and rural Scotland © Scottish Environment LINK Published by Scottish Environment LINK, February 2006 Further copies available at £25 (including p&p) from: Scottish Environment LINK, 2 Grosvenor House, Shore Road, PERTH PH2 7EQ, UK Tel 00 44 (0)1738 630804 Available as a PDF from www.scotlink.org Acknowledgements: Chris Tyler, of Arnisort in Skye for the cartoon series Hugh Womersley, Glasgow, for photos of Sound of Harris & Roineabhal Pat and Angus Macdonald for cover view (aerial) of Roineabhal Turnbull Jeffrey Partnership for photomontage of proposed superquarry Alastair McIntosh for most other photos (some of which are courtesy of Lafarge Aggregates) LINK is a Scottish charity under Scottish Charity No SC000296 and a Scottish Company limited by guarantee and without a share capital under Company No SC250899 The Battle for Roineabhal Page 2 of 144 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Lingerabay Facts & Figures: An Overview 3. The Stone Age – Superquarry Prehistory 4. Landscape Quality Guardians – the advent of the LQG 5. Views from Harris – Work versus Wilderness 6. 83 Days of Advocacy – the LQG takes Counsel 7. 83 Days of Advocacy – Voices from Harris 8. -

D NORTH HARRIS UIG, MORSGAIL and ALINE in LEWIS

GEOLOGY of the OUTER HEBRIDES -d NORTH HARRIS and UIG, MORSGAIL and ALINE in LEWIS. by Robert M. Craig, iii.A., B.Sc. GEOLOGY of the OUTER HEBRIDES - NORTH HARRIS and UIG, 'MORSGAIL and ALINE in LEWIS. CONTENTS. I. Introduction. TI. Previous Literature. III. Summary of the Rock Formations. IV. Descriptions of the Rock Formations - 1. The Archaean Complex. (a). Biotite- Gneiss. b). Hornblende -biotite- gneiss. d).). Basic rocks associated with (a) and (b). Acid hornblende -gneiss intrusive into (a) and (b). e . Basic Rocks intrusive into (a) and (b). f Ultra -basic Rocks. g ? Paragneisses. h The Granite- Gneiss. i Pegmatites. ?. Zones of Crushing and Crushed Rocks. S. Later Dykes. V. Physical Features. VI. Glaciation and Glacial Deposits. VII. Recent Changes. VIII. Explanation of Illustrations. I. INTRODUCTION. The area of the Outer Hebrides described in this paper includes North Harris and the Uig, Morsgail and Aline districts in Lewis. In addition, a narrow strip of country is included, north of Loch Erisort and extending eastwards from Balallan as far as the river Laxay on the estate of Soval. North Harris and its adjacent islands such as Scarp and Fladday on the west, and Soay in West Loch Tarbert on the south, forms part of Inverness - shire; Uig, Morsgail and Aline are included in Ross- shire. North Harris, joined to South Harris by the narrow isthmus at Tarbert, is bounded on the south by East and West Loch Tarbert, on the east by Loch Seaforb and on the west by the Atlantic Ocean. Its northern limit is formed partly by Loch Resort and partly by a land boundary much disputed in the past, passing from the head of Loch Resort between Stulaval and Rapaire to Mullach Ruisk and thence to the Amhuin a Mhuil near Aline Lodge on Loch Seaforth. -

N: a Sea Monster of a Research Project

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects Honors Program 5-2019 N: A Sea Monster of a Research Project Adrian Jay Thomson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Thomson, Adrian Jay, "N: A Sea Monster of a Research Project" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. 424. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/424 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. N: A SEA MONSTER OF A RESEARCH PROJECT by Adrian Jay Thomson Capstone submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with UNIVERSITY HONORS with a major in English- Creative Writing in the Department of English Approved: UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT SPRING2019 Abstract Ever since time and the world began, dwarves have always fought cranes. Ever since ships set out on the northern sea, great sea monsters have risen to prey upon them. Such are the basics of life in medieval and Renaissance Scandinavia , Iceland, Scotland and Greenland, as detailed by Olaus Magnus' Description of the Northern Peoples (1555) , its sea monster -heavy map , the Carta Marina (1539), and Abraham Ortelius' later map of Iceland, Islandia (1590). I first learned of Olaus and Ortelius in the summer of 2013 , and while drawing my own version of their sea monster maps a thought hit me: write a book series , with teenage characters similar to those in How to Train Your Dragon , but set it amongst the lands described by Olaus , in a frozen world badgered by the sea monsters of Ortelius. -

Supernatural/Speculative/Paranormal

Below in no specific order is a list of back cover blurbs in Supernatural/Speculative/Paranormal/Horror/Fantasy/Ghost genres that I wrote from scratch or revised (the original blurb is included first, followed by my revision) as well as the high-concept (75- and/or 150 words or less) blurb I wrote for it, if the blurb wasn't already in that word count. Note: Unless specified otherwise, I also wrote the series blurbs. If you're looking for something specific, click Control F to search for it. Karen Wiesner Dangerous Waters Series by Dee Lloyd http://www.deelloyd.com/ Paranormal Romance Series blurb: Dashing heroes set out to protect the women of their dreams as they travel by boat over the Caribbean and the Bahamas, even to a clear lake in Muskoka, where romance--and deception- -will take them all into Dangerous Waters. [39 words] Dashing heroes set out to protect the women of their dreams when romance--and deception-- will take them all into Dangerous Waters. [22 words] Book 1: Change of Plans Original blurb: Mike and Sara didn't plan on falling in love... Mike was determined to change his image from “Mr. Nice Guy” to “dangerous and exciting male on the prowl.” He had narrowly missed marrying the wrong woman, who had eloped with her boss before he arrived home from a contract job in Africa. Disillusioned by her broken promise and angry with women in general, Mike plans to find a fun-loving woman to share his honeymoon stateroom. Sara has never been in love, but she does want a family. -

On the Trail of Scotlands Myths and Legends Free

FREE ON THE TRAIL OF SCOTLANDS MYTHS AND LEGENDS PDF Stuart McHardy | 152 pages | 01 Apr 2005 | LUATH PRESS LTD | 9781842820490 | English | Edinburgh, United Kingdom Myths and legends play a major role in Scotland's culture and history. From before the dawn of history, the early ancestors of the people we now know as the Scots, built impressive monuments which have caught the imagination of those who have followed in their wake. Stone circles, chambered cairns, brochs and vitrified forts stir within us something primeval and stories have been born from their mystical qualities. Scottish myths and legends have drawn their inspiration from many sources. Every land has its tales of dragons, but Scotland is an island country, bound to the sea. Cierein Croin, a gigantic sea serpent is said to be the largest creature ever. Yes, Nessie is classified as a dragon although she may be a member of that legendary species, the each-uisge or water horse. However, the cryptozoologists will swear that she is a leftover plesiosaurus. The Dalriadan Scots shared more than the Gaelic tongue with their trading partners in Ireland. They were great storytellers and had a culture rich in tales of heroes and mythical creatures. Many of the similarities between Irish and Scottish folklore can be accounted for by their common Celtic roots. Tales of Finn On the Trail of Scotlands Myths and Legends Cumhall and his warrior band, the Fianna are as commonplace on the Hebrides as in Ireland. Many of the myths centre around the cycle of nature and the passing of the seasons with the battle between light and darkness, summer and winter. -

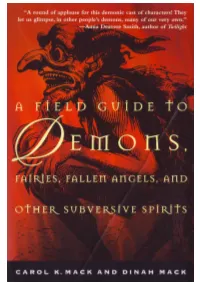

A-Field-Guide-To-Demons-By-Carol-K

A FIELD GUIDE TO DEMONS, FAIRIES, FALLEN ANGELS, AND OTHER SUBVERSIVE SPIRITS A FIELD GUIDE TO DEMONS, FAIRIES, FALLEN ANGELS, AND OTHER SUBVERSIVE SPIRITS CAROL K. MACK AND DINAH MACK AN OWL BOOK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY NEW YORK Owl Books Henry Holt and Company, LLC Publishers since 1866 175 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10010 www.henryholt.com An Owl Book® and ® are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC. Copyright © 1998 by Carol K. Mack and Dinah Mack All rights reserved. Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd. Library of Congress-in-Publication Data Mack, Carol K. A field guide to demons, fairies, fallen angels, and other subversive spirits / Carol K. Mack and Dinah Mack—1st Owl books ed. p. cm. "An Owl book." Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-6270-0 ISBN-10: 0-8050-6270-X 1. Demonology. 2. Fairies. I. Mack, Dinah. II. Title. BF1531.M26 1998 99-20481 133.4'2—dc21 CIP Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets. First published in hardcover in 1998 by Arcade Publishing, Inc., New York First Owl Books Edition 1999 Designed by Sean McDonald Printed in the United States of America 13 15 17 18 16 14 This book is dedicated to Eliza, may she always be surrounded by love, joy and compassion, the demon vanquishers. Willingly I too say, Hail! to the unknown awful powers which transcend the ken of the understanding. And the attraction which this topic has had for me and which induces me to unfold its parts before you is precisely because I think the numberless forms in which this superstition has reappeared in every time and in every people indicates the inextinguish- ableness of wonder in man; betrays his conviction that behind all your explanations is a vast and potent and living Nature, inexhaustible and sublime, which you cannot explain. -

Encyclopedia of CELTIC MYTHOLOGY and FOLKLORE

the encyclopedia of CELTIC MYTHOLOGY AND FOLKLORE Patricia Monaghan The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore Copyright © 2004 by Patricia Monaghan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Monaghan, Patricia. The encyclopedia of Celtic mythology and folklore / Patricia Monaghan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4524-0 (alk. paper) 1. Mythology, Celtic—Encyclopedias. 2. Celts—Folklore—Encyclopedias. 3. Legends—Europe—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BL900.M66 2003 299'.16—dc21 2003044944 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K. Arroyo Cover design by Cathy Rincon Printed in the United States of America VB Hermitage 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS 6 INTRODUCTION iv A TO Z ENTRIES 1 BIBLIOGRAPHY 479 INDEX 486 INTRODUCTION 6 Who Were the Celts? tribal names, used by other Europeans as a The terms Celt and Celtic seem familiar today— generic term for the whole people.