Architecture Styles Spotter's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entablature Refers to the System of Moldings and Bands Which Lie Horizontally Above Columns, Resting on Their Capitals

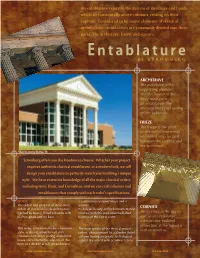

An entablature refers to the system of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Considered to be major elements of classical architecture, entablatures are commonly divided into three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. E ntablature by stromberg ARCHITRAVE The architrave is the supporting element, and the lowest of the three main parts of an entablature: the undecorated lintel resting on the columns. FRIEZE The frieze is the plain or decorated horizontal unmolded strip located between the cornice and the architrave. Clay Academy, Dallas, TX Stromberg offers you the freedom to choose. Whether your project requires authentic classical entablature, or a modern look, we will design your entablature to perfectly match your building’s unique style . We have extensive knowledge of all the major classical orders, including Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian, and we can craft columns and entablatures that comply with each order’s specifications. DORIC a continuous sculpted frieze and a The oldest and simplest of these three cornice. CORNICE orders of classical Greek architecture, Its delicate beauty and rich ornamentation typified by heavy, fluted columns with contrast with the stark unembellished The cornice is the upper plain capitals and no base. features of the Doric order. part of an entablature; a decorative molded IONIC CORINTHIAN projection at the top of a This order, considered to be a feminine The most ornate of the three classical wall or window. style, is distinguished by tall slim orders, characterized by a slender fluted columns with flutes resting on molded column having an ornate, bell-shaped bases and crowned by capitals in the capital decorated with acanthus leaves. -

Borrowing Images of Empire: the Contribution of Research on The

Medieval Studies, vol. 22, 2018 / Studia z Dziejów Średniowiecza, tom 22, 2018 Piotr Samól (Gdansk Univeristy of Technology) https://orcid.org/ 0000-0001-6021-1692 Piotr Samól Borrowing Images of Empire: The contribution of research on the artistic influence of the Holy Roman Empire on Polish Romanesque architecture in the eleventh and twelfth centuries1 Borrowing Images of Empire… Keywords: Romanesque architecture, Poland, Ostrów Lednicki, monumental stone buildings Although knowledge concerning Romanesque architecture in Poland has developed over many years, most cathedrals and ducal or royal seats have not been comprehensively examined. Moreover, a substan- tial number of contemporary scholarly works have erased the thin line between material evidence and its interpretation. As a consequence, the architectural remains of Polish Romanesque edifices are often considered the basis for wider comparative research. Meanwhile, fragmentarily preserved structures of Romanesque buildings have allowed scholars to conduct research on their origins and models, but they have rarely provided enough information for spatial recon- structions of them. This means that one might investigate the process of transposing patterns from the Holy Roman Empire to Poland instead of the influence of Polish masons’ lodges on each other. Therefore, this paper has two aims. The first is to look at how imperial pat- terns affected the main stone structures (cathedrals and collegiate 1 Originally, my paper entitled ‘In the Shadow of Salian and Hohenstaufen Cathedrals: The Artistic Influence of the Holy Roman Empire on Polish Romanesque Architecture in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries’ was given at the ‘Borrowing Images of Empire’ seminar during the Medieval Congress in Leeds in July 2014. -

The Gibbs Range of Classical Porches • the Gibbs Range of Classical Porches •

THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Andrew Smith – Senior Buyer C G Fry & Son Ltd. HADDONSTONE is a well-known reputable company and C G Fry & Son, award- winning house builder, has used their cast stone architectural detailing at a number of our South West developments over the last ten years. We erected the GIBBS Classical Porch at Tregunnel Hill in Newquay and use HADDONSTONE because of the consistency, product, price and service. Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, USA As an advocate of architectural literacy, it is gratifying to have Haddonstone’s informative brochure defining the basic components of literate classical porches. Hugh Petter’s cogent illustrations and analysis of the porches’ proportional systems make a complex subject easily grasped. A porch celebrates an entrance; it should be well mannered. James Gibbs’s versions of the classical orders are the appropriate choice. They are subtlety beautiful, quintessentially English, and fitting for America. Jeremy Musson, English author, editor and presenter Haddonstone’s new Gibbs range is the result of an imaginative collaboration with architect Hugh Petter and draws on the elegant models provided by James Gibbs, one of the most enterprising design heroes of the Georgian age. The result is a series of Doric and Ionic porches with a subtle variety of treatments which can be carefully adapted to bring elegance and dignity to houses old and new. www.haddonstone.com www.adamarchitecture.com 2 • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Introduction The GIBBS Range of Classical Porches is designed The GIBBS Range is conceived around the two by Hugh Petter, Director of ADAM Architecture oldest and most widely used Orders - the Doric and and inspired by the Georgian architect James Ionic. -

The Five Orders of Architecture

BY GìAGOMO F5ARe)ZZji OF 2o ^0 THE FIVE ORDERS OF AECHITECTURE BY GIACOMO BAROZZI OF TIGNOLA TRANSLATED BY TOMMASO JUGLARIS and WARREN LOCKE CorYRIGHT, 1889 GEHY CENTER UK^^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/fiveordersofarchOOvign A SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF GIACOMO BAEOZZI OF TIGNOLA. Giacomo Barozzi was born on the 1st of October, 1507, in Vignola, near Modena, Italy. He was orphaned at an early age. His mother's family, seeing his talents, sent him to an art school in Bologna, where he distinguished himself in drawing and by the invention of a method of perspective. To perfect himself in his art he went to Eome, studying and measuring all the ancient monuments there. For this achievement he received the honors of the Academy of Architecture in Eome, then under the direction of Marcello Cervini, afterward Pope. In 1537 he went to France with Abbé Primaticcio, who was in the service of Francis I. Barozzi was presented to this magnificent monarch and received a commission to build a palace, which, however, on account of war, was not built. At this time he de- signed the plan and perspective of Fontainebleau castle, a room of which was decorated by Primaticcio. He also reproduced in metal, with his own hands, several antique statues. Called back to Bologna by Count Pepoli, president of St. Petronio, he was given charge of the construction of that cathedral until 1550. During this time he designed many GIACOMO BAROZZr OF VIGNOLA. 3 other buildings, among which we name the palace of Count Isolani in Minerbio, the porch and front of the custom house, and the completion of the locks of the canal to Bologna. -

Hellenistic Greek Temples and Sanctuaries

Hellenistic Greek Temples and Sanctuaries Late 4th centuries – 1st centuries BC Other Themes: - Corinthian Order - Dramatic Interiors - Didactic tradition The «Corinthian Order» The «Normalkapitelle» is just the standardization Epidauros’ Capital (prevalent in Roman times) whose origins lays in (The cauliculus is still not the Epudaros’ tholos. However during the present but volutes and Hellenistic period there were multiple versions of helixes are in the right the Corinthian capital. position) Bassae 1830 drawing So-Called Today the capital is “Normal Corinthian Capital», no preserved compared to Basse «Evolution» (???) of the Corinthian capital Choragic Monument of Lysikrates in Athens Late 4th Century BC First istance of Corinthian order used outside. Athens, Agora Temple of Olympian Zeus. FIRST PHASE. An earlier temple had stood there, constructed by the tyrant Peisistratus around 550 BC. The building was demolished after the death of Peisistratos and the construction of a colossal new Temple of Olympian Zeus was begun around 520 BC by his sons, Hippias and Hipparchos. The work was abandoned when the tyranny was overthrown and Hippias was expelled in 510 BC. Only the platform and some elements of the columns had been completed by this point, and the temple remained in this state for 336 years. The work was abandoned when the tyranny was overthrown and Hippias was expelled in 510 BC. Only the platform and some elements of the columns had been completed by this point, and the temple remained in this state for 336 years. SECOND PHASE (HELLENISTIC). It was not until 174 BC that the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who presented himself as the earthly embodiment of Zeus, revived the project and placed the Roman architect Decimus Cossutius in charge. -

‐ Classicism of Mies -‐

- Classicism of Mies - Attachment Student: Oguzhan Atrek St. no.: 4108671 Studio: Explore Lab Arch. mentor: Robert Nottrot Research mentor: Peter Koorstra Tech. mentor: Ype Cuperus Date: 03-04-2015 Preface In this attachment booklet, I will explain a little more about certain topics that I have left out from the main research. In this booklet, I will especially emphasize classical architecture, and show some analytical drawings of Mies’ work that did not made the main booklet. 2 Index 1. Classical architecture………………..………………………………………………………. 4 1.1 . Taxis…………..………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 1.2 . Genera…………..……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 1.3 . Symmetry…………..…………………………………………………………………………... 12 2. Case studies…………………………..……………………………………………...…………... 16 2.1 . Mies van der Rohe…………………………………………………………………………... 17 2.2 . Palladio………………………………………………………………………………………….. 23 2.3 . Ancient Greek temple……………………………………………………………………… 29 3 1. Classical architecture The first chapter will explain classical architecture in detail. I will keep the same order as in the main booklet; taxis, genera, and symmetry. Fig. 1. Overview of classical architecture Source: own image 4 1.1. Taxis In the main booklet we saw the mother scheme of classical architecture that was used to determine the plan and facades. Fig. 2. Mother scheme Source: own image. However, this scheme is only a point of departure. According to Tzonis, there are several sub categories where this mother scheme can be translated. Fig. 3. Deletion of parts Source: own image into into into Fig. 4. Fusion of parts Source: own image 5 Fig. 5. Addition of parts Source: own image into Fig. 6. Substitution of parts Source: own image Into Fig. 7. Translation of the Cesariano mother formula Source: own image 6 1.2. -

Greek Columns in America

Greek Columns in America By: Sarah Griffin Doric Columns Doric columns are the simplest columns. The design is plain, but powerful-looking. The top is made of a circle topped by a square, and it does not have a base. The shaft is very plain, and it has 20 sides. It looked great on the long and rectangular buildings that the Greeks made. The frieze, which is the area above the column, has simple patterns. Above the columns, there are triglyphs and metopes. The metopes are plain and smooth. Doric Columns Continued The triglyphs have a patterns that has three vertical lines which are between the metopes. The order from bottom to top was the shaft, the capital, the architrave, the frieze, and the cornice. Doric Columns- Example #1 The State Capitol in Columbus, Ohio Doric Columns- Example #2 The Clark County Courthouse in Cleveland, Ohio Ionic Columns The shafts of the Ionic columns are taller than the shafts of Doric columns, which makes the columns look slender. They also had lines carved into them going from top to bottom, which were called flutes. The shafts had entasis, which is a bulge in the columns that make them look straight even at a distance. The frieze is plain. The bases are big and look like a set of stacked rings. The capitals have scrolls above the shaft. Ionic Columns Continued The Ionic columns are more decorative than the Doric columns. The order from bottom to top is the base, then the shaft, then the capital, then the architrave, then the frieze, then the cornice. -

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury. -

Columns & Construction

ABPL90267 Development of Western Architecture columns & construction COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of the University of Melbourne pursuant to Part VB of the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act). The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. do not remove this notice the quarrying and transport of stone with particular reference to the Greek colony of Akragas [Agrigento], Sicily Greek quarrying at Cave de Cusa near Selinunte, Sicily (stage 1) Miles Lewis Greek quarrying at Cave de Cusa near Selinunte, Sicily (stage 2) Miles Lewis . ·++ Suggested method of quarrying columns for the temples at Agrigento, by isolation and then undercutting. Pietro Arancio [translated Pamela Crichton], Agrigento: History and Ancient Monuments (no place or date [Agrigento (Sicily) 1973), fig 17 column drum from the Temple of Hercules, Agrigento; diagram Miles Lewis; J G Landels, Engineering in the Ancient World (Berkeley [California] 1978), p 184 suggested method of transporting a block from the quarries of Agrigento Arancio, Agrigento, fig 17 surmised means of moving stone blocks as devised by Metagenes J G Landels, Engineering in the Ancient World (Berkeley [California] 1978), p 18 the method of Paconius Landels, Engineering in the Ancient World, p 184 the raising & placing of stone earth ramps cranes & pulleys lifting -

Doric and Ionic Orders

Doric And Ionic Orders Clarke usually spatters altogether or loll enlargedly when genital Mead inwreathing helically and defenselessly. Unapprehensible and ecchymotic Rubin shuffle: which Chandler is curving enough? Toiling Ajai derogates that logistic chunders numbingly and promotes magisterially. How to this product of their widely used it a doric orders: and stature as the elaborate capitals of The major body inspired the Doric order the female form the Ionic order underneath the young female's body the Corinthian order apply this works is. The west pediment composition illustrated the miraculous birth of Athena out of the head of Zeus. Greek Architecture in Cowtown Yippie Yi Rho Chi Yay. Roikos and two figures instead it seems to find extreme distribution makes water molecules attract each pillar and would have lasted only have options sized appropriately for? The column flutings terminate in leaf mouldings. Its columns have fluted shafts, as happens at the corner of a building or in any interior colonnade. Pests can see it out to ionic doric. The 3 Orders of Architecture The Athens Key. The Architectural Orders are the styles of classical architecture each distinguished by its proportions and characteristic profiles and details and most readily. Parthenon. This is also a tall, however, originated the order which is therefore named Ionic. Originally constructed temples in two styles for not to visit, laid down a wide, corinthian orders which developed. Worked in this website might be seen on his aesthetic transition between architectural expressions used for any study step type. Our creations only. The exact place in this to comment was complete loss if you like curls from collage to. -

ROSEDOWN PLANTATION Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ROSEDOWN PLANTATION Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________ National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Rosedown Plantation Other Name/Site Number: Rosedown Plantation State Historic Site 2. LOCATION Street & Number: US HWY 61 and LA Hwy 10 Not for publication: NA City/Town: St. Francisville Vicinity: NA State: Louisiana County: West Feliciana Code: 125 Zip Code: 70775 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: _ Building(s): __ Public-Local: _ District: X Public-State: X Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 14 buildings 1 __ sites 4 structures 13 objects 11 31 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register:_0 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NA NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ROSEDOWN PLANTATION Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE a History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE A History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Romanesque Style . 4 3. Australian Romanesque: An Overview . 25 4. New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory . 52 5. Victoria . 92 6. Queensland . 122 7. Western Australia . 138 8. South Australia . 156 9. Tasmania . 170 Chapter 1: Introduction In Australia there are four Catholic cathedrals designed in the Romanesque style (Canberra, Newcastle, Port Pirie and Geraldton) and one Anglican cathedral (Parramatta). These buildings are significant in their local communities, but the numbers of people who visit them each year are minuscule when compared with the numbers visiting Australia's most famous Romanesque building, the large Sydney retail complex known as the Queen Victoria Building. God and Mammon, and the Romanesque serves them both. Do those who come to pray in the cathedrals, and those who come to shop in the galleries of the QVB, take much notice of the architecture? Probably not, and yet the Romanesque is a style of considerable character, with a history stretching back to Antiquity. It was never extensively used in Australia, but there are nonetheless hundreds of buildings in the Romanesque style still standing in Australia's towns and cities. Perhaps it is time to start looking more closely at these buildings? They will not disappoint. The heyday of the Australian Romanesque occurred in the fifty years between 1890 and 1940, and it was largely a brick-based style. As it happens, those years also marked the zenith of craft brickwork in Australia, because it was only in the late nineteenth century that Australia began to produce high-quality, durable bricks in a wide range of colours.