The Diminution of the Classical Column: Visual Sensibility In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entablature Refers to the System of Moldings and Bands Which Lie Horizontally Above Columns, Resting on Their Capitals

An entablature refers to the system of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Considered to be major elements of classical architecture, entablatures are commonly divided into three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. E ntablature by stromberg ARCHITRAVE The architrave is the supporting element, and the lowest of the three main parts of an entablature: the undecorated lintel resting on the columns. FRIEZE The frieze is the plain or decorated horizontal unmolded strip located between the cornice and the architrave. Clay Academy, Dallas, TX Stromberg offers you the freedom to choose. Whether your project requires authentic classical entablature, or a modern look, we will design your entablature to perfectly match your building’s unique style . We have extensive knowledge of all the major classical orders, including Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian, and we can craft columns and entablatures that comply with each order’s specifications. DORIC a continuous sculpted frieze and a The oldest and simplest of these three cornice. CORNICE orders of classical Greek architecture, Its delicate beauty and rich ornamentation typified by heavy, fluted columns with contrast with the stark unembellished The cornice is the upper plain capitals and no base. features of the Doric order. part of an entablature; a decorative molded IONIC CORINTHIAN projection at the top of a This order, considered to be a feminine The most ornate of the three classical wall or window. style, is distinguished by tall slim orders, characterized by a slender fluted columns with flutes resting on molded column having an ornate, bell-shaped bases and crowned by capitals in the capital decorated with acanthus leaves. -

The Architecture of Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, in Ten Books

www.e-rara.ch The architecture of Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, in ten books Vitruvius London, 1826 Bibliothek Werner Oechslin Shelf Mark: A04a ; app. 851 Persistent Link: http://dx.doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-19442 Life of Vitruvius. www.e-rara.ch Die Plattform e-rara.ch macht die in Schweizer Bibliotheken vorhandenen Drucke online verfügbar. Das Spektrum reicht von Büchern über Karten bis zu illustrierten Materialien – von den Anfängen des Buchdrucks bis ins 20. Jahrhundert. e-rara.ch provides online access to rare books available in Swiss libraries. The holdings extend from books and maps to illustrated material – from the beginnings of printing to the 20th century. e-rara.ch met en ligne des reproductions numériques d’imprimés conservés dans les bibliothèques de Suisse. L’éventail va des livres aux documents iconographiques en passant par les cartes – des débuts de l’imprimerie jusqu’au 20e siècle. e-rara.ch mette a disposizione in rete le edizioni antiche conservate nelle biblioteche svizzere. La collezione comprende libri, carte geografiche e materiale illustrato che risalgono agli inizi della tipografia fino ad arrivare al XX secolo. Nutzungsbedingungen Dieses Digitalisat kann kostenfrei heruntergeladen werden. Die Lizenzierungsart und die Nutzungsbedingungen sind individuell zu jedem Dokument in den Titelinformationen angegeben. Für weitere Informationen siehe auch [Link] Terms of Use This digital copy can be downloaded free of charge. The type of licensing and the terms of use are indicated in the title information for each document individually. For further information please refer to the terms of use on [Link] Conditions d'utilisation Ce document numérique peut être téléchargé gratuitement. -

The Gibbs Range of Classical Porches • the Gibbs Range of Classical Porches •

THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Andrew Smith – Senior Buyer C G Fry & Son Ltd. HADDONSTONE is a well-known reputable company and C G Fry & Son, award- winning house builder, has used their cast stone architectural detailing at a number of our South West developments over the last ten years. We erected the GIBBS Classical Porch at Tregunnel Hill in Newquay and use HADDONSTONE because of the consistency, product, price and service. Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, USA As an advocate of architectural literacy, it is gratifying to have Haddonstone’s informative brochure defining the basic components of literate classical porches. Hugh Petter’s cogent illustrations and analysis of the porches’ proportional systems make a complex subject easily grasped. A porch celebrates an entrance; it should be well mannered. James Gibbs’s versions of the classical orders are the appropriate choice. They are subtlety beautiful, quintessentially English, and fitting for America. Jeremy Musson, English author, editor and presenter Haddonstone’s new Gibbs range is the result of an imaginative collaboration with architect Hugh Petter and draws on the elegant models provided by James Gibbs, one of the most enterprising design heroes of the Georgian age. The result is a series of Doric and Ionic porches with a subtle variety of treatments which can be carefully adapted to bring elegance and dignity to houses old and new. www.haddonstone.com www.adamarchitecture.com 2 • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Introduction The GIBBS Range of Classical Porches is designed The GIBBS Range is conceived around the two by Hugh Petter, Director of ADAM Architecture oldest and most widely used Orders - the Doric and and inspired by the Georgian architect James Ionic. -

The Five Orders of Architecture

BY GìAGOMO F5ARe)ZZji OF 2o ^0 THE FIVE ORDERS OF AECHITECTURE BY GIACOMO BAROZZI OF TIGNOLA TRANSLATED BY TOMMASO JUGLARIS and WARREN LOCKE CorYRIGHT, 1889 GEHY CENTER UK^^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/fiveordersofarchOOvign A SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF GIACOMO BAEOZZI OF TIGNOLA. Giacomo Barozzi was born on the 1st of October, 1507, in Vignola, near Modena, Italy. He was orphaned at an early age. His mother's family, seeing his talents, sent him to an art school in Bologna, where he distinguished himself in drawing and by the invention of a method of perspective. To perfect himself in his art he went to Eome, studying and measuring all the ancient monuments there. For this achievement he received the honors of the Academy of Architecture in Eome, then under the direction of Marcello Cervini, afterward Pope. In 1537 he went to France with Abbé Primaticcio, who was in the service of Francis I. Barozzi was presented to this magnificent monarch and received a commission to build a palace, which, however, on account of war, was not built. At this time he de- signed the plan and perspective of Fontainebleau castle, a room of which was decorated by Primaticcio. He also reproduced in metal, with his own hands, several antique statues. Called back to Bologna by Count Pepoli, president of St. Petronio, he was given charge of the construction of that cathedral until 1550. During this time he designed many GIACOMO BAROZZr OF VIGNOLA. 3 other buildings, among which we name the palace of Count Isolani in Minerbio, the porch and front of the custom house, and the completion of the locks of the canal to Bologna. -

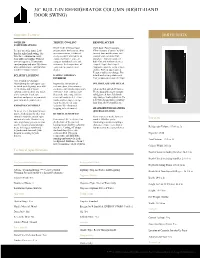

30” Built-In Refrigerator Column (Right-Hand Door Swing)

30” BUILT-IN REFRIGERATOR COLUMN (RIGHT-HAND DOOR SWING) Signature Features JBRFR30IGX OVER 250 TRINITY COOLING REMOTE ACCESS CONFIGURATIONS Revel in the trinity of food Open door. Power outages. Freezer or refrigerator. Left- preservation: three zones, three Filter changes. Connect to WiFi hand or right-hand swing. One, precision sensors, calibrated for real-time notifications and two, three columns in a row. every second. Fortified by an control your columns from Four different widths. With 12 exposed air tower, you can anywhere. Tap and swipe on one-unit options, 75 two-unit conquer humidity levels and both iOS and Android devices. combinations and over 250 three- customize the temperature of <sup>1</sup><br><sup>1 unit combinations, configuration each zone to your deepest Appliance must be set to remote is where bespoke begins. desires. enable. WiFi & app required. Features subject to change. For ECLIPTIC LIGHTING DARING OBSIDIAN details and privacy statement, INTERIOR visit jennair.com/connect.</sup> Live beyond the shadow. Abandoning the dark spots cast Inspired by the beauty of SOLID GLASS AND METAL by dated puck lighting, over 650 volcanic glass, this industry- LEDs frame and fill your exclusive dark finish erupts with All-metal bin and shelf frames. column, coming alive at a touch reflective, high-contrast style. Thick, naturally odor-resistant of the controls. Each zone Reject the unfeeling, lifeless solid glass. A forcefield at the awakens and pulses as you mold vessel of harsh steel. Let fine edge that prevents spillovers. To your column to your desires. foods and beverages emerge hell with cheap plastic in luxury from the interior of your door bins, shelves and liners. -

The Nonstop Record

Admissions As administrative coordinator of the bold and to make courageous choices.” by Ed M. Koziarski three-person executive collective that “They realize that this is more oversees Nonstop, Eklund-Leen is re- than just a temporary bridge between he Nonstop Liberal Arts Insti- sponsible for admissions. the Antioch-of-the-past and the An- tute begins holding classes Sept. “Scott’s estimate of 80 is as tioch-of-the-future,” Kay continued, T4 with the entire village of Yel- good as any, and we have discussed a “but a groundbreaking educational low Springs as its campus. 22 faculty range between 50 and 100” students,” venture that can offer them much more are continuing from Antioch College, Eklund-Leen said. than they could expect from a tradi- offering a curriculum that retains ma- At press time Nonstop was in tional college: experiential learning in jor elements from recent years at the the process of hiring a recruitment fa- its most radical sense, the unique op- college while taking a number of in- cilitator whose position would be dedi- portunity to be part of the construction novative new steps. cated to this endeavor. Eklund-Leen of your own education, participation in But what of the students? Who said that absence of that position has a genuine academic community under will come to a school that lacks accred- “slowed down our efforts” to date. shared governance, and the knowledge itation or the ability to confer degrees? Jeanne Kay, a continuing stu- that by being part of Nonstop, they Nonstop professor Scott War- dent who sits on Nonstop’s governing are participating in a social movement ren told the Associated Press July 11 council ExCil, has been answering in- with a broad political scope. -

HOME OFFICE SOLUTIONS Hettich Ideas Book Table of Contents

HOME OFFICE SOLUTIONS Hettich Ideas Book Table of Contents Eight Elements of Home Office Design 11 Home Office Furniture Ideas 15 - 57 Drawer Systems & Hinges 58 - 59 Folding & Sliding Door Systems 60 - 61 Further Products 62 - 63 www.hettich.com 3 How will we work in the future? This is an exciting question what we are working on intensively. The fact is that not only megatrends, but also extraordinary events such as a pandemic are changing the world and influencing us in all areas of life. In the long term, the way we live, act and furnish ourselves will change. The megatrend Work Evolution is being felt much more intensively and quickly. www.hettich.com 5 Work Evolution Goodbye performance society. Artificial intelligence based on innovative machines will relieve us of a lot of work in the future and even do better than we do. But what do we do then? That’s a good question, because it puts us right in the middle of a fundamental change in the world of work. The creative economy is on the advance and with it the potential development of each individual. Instead of a meritocracy, the focus is shifting to an orientation towards the strengths and abilities of the individual. New fields of work require a new, flexible working environment and the work-life balance is becoming more important. www.hettich.com 7 Visualizing a Scenario Imagine, your office chair is your couch and your commute is the length of your hallway. Your snack drawer is your entire pantry. Do you think it’s a dream? No! Since work-from-home is very a reality these days due to the pandemic crisis 2020. -

Andrián Pertout

Andrián Pertout Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition Volume 1 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Produced on acid-free paper Faculty of Music The University of Melbourne March, 2007 Abstract Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition encompasses the work undertaken by Lou Harrison (widely regarded as one of America’s most influential and original composers) with regards to just intonation, and tuning and scale systems from around the globe – also taking into account the influential work of Alain Daniélou (Introduction to the Study of Musical Scales), Harry Partch (Genesis of a Music), and Ben Johnston (Scalar Order as a Compositional Resource). The essence of the project being to reveal the compositional applications of a selection of Persian, Indonesian, and Japanese musical scales utilized in three very distinct systems: theory versus performance practice and the ‘Scale of Fifths’, or cyclic division of the octave; the equally-tempered division of the octave; and the ‘Scale of Proportions’, or harmonic division of the octave championed by Harrison, among others – outlining their theoretical and aesthetic rationale, as well as their historical foundations. The project begins with the creation of three new microtonal works tailored to address some of the compositional issues of each system, and ending with an articulated exposition; obtained via the investigation of written sources, disclosure -

Mobile Column Lift System Is the Faster and Easier Choice for Your Maintenance Facility

MobileHEAVY DUTY Column LIFTING SYSTEMS Ergonomic FLEETVersatile Performance Productive Reliable FAST Dependable Mobile Buy America World Best Techs TM Legendary TM Red FireLRemoteE controlledADERHEAVY DUTY Battery Efficient MACHCareer Extender ENVIRONMENTALLY FRIENDLY TM EmployeeWireless Retention Patented Flex Innovative Adjustable www.rotarylift.com A Shown: MCHM419U1A00 / Wireless remote-controlled model N D D E VALIDAT TM WIRELESS CONTROLS FLEXMAX NO CABLES / NO CORDS REMOTE-CONTROLLED LIFTING Unmatched lifting versatility and flexibility with the mobility to monitor and adjust your columns anywhere in your shop. Premium FLEXMAXTM lifts provide wireless, remote-controlled flexibility LIFT UP TO 150,400 LBS. plus added operational controls at each column giving technicians the choice to work in the most comfortable, productive and efficient way possible. Ergonomic, wireless hand-held remote control walks the technician through the system set up. Status lights indicate standby or paired columns. Controller features include: • On/off power button with info screen • 2-speed joystick control with auto resume FLEXMAX419 • Single lower-to-lock button with E-stop control A N D 18,800 lbs. capacity column D TE VALIDA • Remote battery indicator Shown: MCHM419U100 • Press ProtectTM eliminates accidental button presses • Audible warning when operator is out of range TM Rotary FLEXMAX feature column capacities at • 99 system IDs eliminate communication interference 18,800 lbs. and 14,000 lbs. in multiple configurations. • Height and weight digital display gauge displays Service everything from light-duty passenger vehicles to • Software upgrades can be made wirelessly heavy-duty trucks. This electro-hydraulic system with WATCH THE adjustable lifting forks can be operated in both odd and PRODUCT VIDEO See how fast and even groups of columns. -

The Art of Architecture

LEARNING TO LOOK AT ARCHITECTURE LOOK: Allow yourself to take the time to slow down and look carefully. OBSERVE: Observation is an active process, requiring both time and attention. It is here that the viewer begins to build up a mental catalogue of the building’s You spend time in buildings every day. But how often visual elements. do you really look at or think about their design, their details, and the spaces they create? What did the SEE: Looking is a physical act; seeing is a mental process of perception. Seeing involves recognizing or connecting the information the eyes take in architect want you to feel or think once inside the with your previous knowledge and experiences in order to create meaning. structure? Following the steps in TMA’s Art of Seeing Art™* process can help you explore architecture on DESCRIBE: Describing can help you to identify and organize your thoughts about what you have seen. It may be helpful to think of describing as taking a deeper level through close looking. a careful inventory. ANALYZE: Analysis uses the details you identified in your descriptions and LOOK INTERPRET applies reason to make meaning. Once details have been absorbed, you’re ready to analyze what you’re seeing through these four lenses: OBSERVE ANALYZE FORM SYMBOLS IDEAS MEANING SEE DESCRIBE INTERPRET: Interpretation, the final step in the Art of Seeing Art™ process, combines our descriptions and analysis with our previous knowledge and any information we have about the artist and the work—or in this case, * For more information on the Art of Seeing Art and visual literacy, the architect and the building. -

Motivic Development.Mus

Motivic Development Motive Basics - A motive is the smallest recognizable musical idea * Repetition of motives is what lends coherence to a melody - A figure is not considered to be motivic unless it is repeated in some way. - A motive can feature rhythmic elements and/or pitch or interval elements - Any of the characteristic features of a motive can be varied in its repetitions (including pitch and rhythm). * Motives are typically labeled with lowercase letters starting at the end of the alphabet (i.e. z, y, x, w) Motive z # 4 œ & 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ Motivic Development Techniques - repetition: restatement of a motive at the same pitch level * repetition can feature a change of mode (i.e. major to minor) at the same pitch level Repetition Repetition (change of mode) # & 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œbœ œ œ œ - transposition: restatement of a motive at a new pitch level * exact (chromatic) transposition: intervals retain the same quality and size * tonal (diatonic) transposition: intervals retain the same size, but not necessarily same quality * sequence: transposition by the same distance several times in a row - exact: intervals retain same quality and size - tonal: intervals retain the same size, but not necessarily same quality - modified: contains some modifications to interval size to fit within a given harmonic structure - modulating: a sequence which functions to transition the piece into a new key Tonal Transposition Exact Transposition # œ œ œ œ & 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ #œ œ œ œ Tonal Sequence # œ œ œ & 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ - variation: elaboration or simplification by adding or removing passing tones, neighbor tones, etc. -

Preloading Approach to Column Removal in an Existing Building by Pratik Shah, P.E., LEED AP

® Copyright Figure 2. Preloading Approach to Column Removal in an Existing Building By Pratik Shah, P.E., LEED AP 475 Fifth Avenue is an existing building near Bryantmagazine Park at the The building’s structural system is a steel moment frame. The gravity intersection of 41st Street andS Fifth AvenueT inR New York U City. The C system consistsT ofU a cinder concreteR toppingE slab over a wire mesh 24-story, 1920s era building recently underwent a major renovation reinforced concrete slab supported by steel beams spanning between that required structural engineering designs to support the building’s girders. The girders are connected to the columns in both directions architectural elements and to accommodate changes to the mechanical with moment connections, to resist lateral loads. All existing shear and system. The structural scope for the project included strengthening moment connections were riveted, as is typical for buildings of this the second-level flooring system for retail loading; framing of new age. The original structural drawings for the building were unavail- mechanical penthouse; framing of new floor and wall openings to able, so all information necessary for design was obtained in the field. accommodate MEP ductwork and louvers; framing of new canopy, new stair crossover and closing abandoned shafts and openings. One Exploratory Phase challenging aspect of the project was to remove an existing column between Levels 1 and 2 located in the middle of the redesigned lobby Since no structural drawings existed, DeSimone performed exhaustive (Figure 1). This column removal is the primary focus of this article. exploratory work, including structural probes, walkthroughs, and field Figure 1.