Hellenistic Architecture in Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

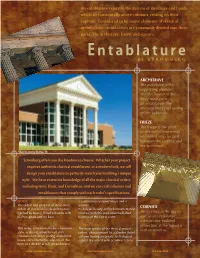

Entablature Refers to the System of Moldings and Bands Which Lie Horizontally Above Columns, Resting on Their Capitals

An entablature refers to the system of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Considered to be major elements of classical architecture, entablatures are commonly divided into three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. E ntablature by stromberg ARCHITRAVE The architrave is the supporting element, and the lowest of the three main parts of an entablature: the undecorated lintel resting on the columns. FRIEZE The frieze is the plain or decorated horizontal unmolded strip located between the cornice and the architrave. Clay Academy, Dallas, TX Stromberg offers you the freedom to choose. Whether your project requires authentic classical entablature, or a modern look, we will design your entablature to perfectly match your building’s unique style . We have extensive knowledge of all the major classical orders, including Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian, and we can craft columns and entablatures that comply with each order’s specifications. DORIC a continuous sculpted frieze and a The oldest and simplest of these three cornice. CORNICE orders of classical Greek architecture, Its delicate beauty and rich ornamentation typified by heavy, fluted columns with contrast with the stark unembellished The cornice is the upper plain capitals and no base. features of the Doric order. part of an entablature; a decorative molded IONIC CORINTHIAN projection at the top of a This order, considered to be a feminine The most ornate of the three classical wall or window. style, is distinguished by tall slim orders, characterized by a slender fluted columns with flutes resting on molded column having an ornate, bell-shaped bases and crowned by capitals in the capital decorated with acanthus leaves. -

The Gibbs Range of Classical Porches • the Gibbs Range of Classical Porches •

THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Andrew Smith – Senior Buyer C G Fry & Son Ltd. HADDONSTONE is a well-known reputable company and C G Fry & Son, award- winning house builder, has used their cast stone architectural detailing at a number of our South West developments over the last ten years. We erected the GIBBS Classical Porch at Tregunnel Hill in Newquay and use HADDONSTONE because of the consistency, product, price and service. Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, USA As an advocate of architectural literacy, it is gratifying to have Haddonstone’s informative brochure defining the basic components of literate classical porches. Hugh Petter’s cogent illustrations and analysis of the porches’ proportional systems make a complex subject easily grasped. A porch celebrates an entrance; it should be well mannered. James Gibbs’s versions of the classical orders are the appropriate choice. They are subtlety beautiful, quintessentially English, and fitting for America. Jeremy Musson, English author, editor and presenter Haddonstone’s new Gibbs range is the result of an imaginative collaboration with architect Hugh Petter and draws on the elegant models provided by James Gibbs, one of the most enterprising design heroes of the Georgian age. The result is a series of Doric and Ionic porches with a subtle variety of treatments which can be carefully adapted to bring elegance and dignity to houses old and new. www.haddonstone.com www.adamarchitecture.com 2 • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Introduction The GIBBS Range of Classical Porches is designed The GIBBS Range is conceived around the two by Hugh Petter, Director of ADAM Architecture oldest and most widely used Orders - the Doric and and inspired by the Georgian architect James Ionic. -

The Five Orders of Architecture

BY GìAGOMO F5ARe)ZZji OF 2o ^0 THE FIVE ORDERS OF AECHITECTURE BY GIACOMO BAROZZI OF TIGNOLA TRANSLATED BY TOMMASO JUGLARIS and WARREN LOCKE CorYRIGHT, 1889 GEHY CENTER UK^^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/fiveordersofarchOOvign A SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF GIACOMO BAEOZZI OF TIGNOLA. Giacomo Barozzi was born on the 1st of October, 1507, in Vignola, near Modena, Italy. He was orphaned at an early age. His mother's family, seeing his talents, sent him to an art school in Bologna, where he distinguished himself in drawing and by the invention of a method of perspective. To perfect himself in his art he went to Eome, studying and measuring all the ancient monuments there. For this achievement he received the honors of the Academy of Architecture in Eome, then under the direction of Marcello Cervini, afterward Pope. In 1537 he went to France with Abbé Primaticcio, who was in the service of Francis I. Barozzi was presented to this magnificent monarch and received a commission to build a palace, which, however, on account of war, was not built. At this time he de- signed the plan and perspective of Fontainebleau castle, a room of which was decorated by Primaticcio. He also reproduced in metal, with his own hands, several antique statues. Called back to Bologna by Count Pepoli, president of St. Petronio, he was given charge of the construction of that cathedral until 1550. During this time he designed many GIACOMO BAROZZr OF VIGNOLA. 3 other buildings, among which we name the palace of Count Isolani in Minerbio, the porch and front of the custom house, and the completion of the locks of the canal to Bologna. -

Decoding the Pantheon Columns

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Graßhoff, G and Berndt, C 2014 Decoding the Pantheon Columns. +LVWRULHV Architectural Histories, 2(1): 18, pp. 1-14, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/ ah.bl RESEARCH ARTICLE Decoding the Pantheon Columns Gerd Graßhoff* and Christian Berndt* The goal of this study has been to reconstruct the design principles underlying the construction of the Pantheon’s portico columns as well as to demonstrate how digital investigation methods and models can be used to improve our understanding of ancient architectural knowledge. Thanks to the data of the Bern Digital Pantheon Model, a synthesis of all the scanned surface points obtained during a digitization cam- paign of the Karman Center for Advanced Studies in the Humanities of the University of Bern in 2005, we have been able to determine empirically the column profiles of the portico with unprecedented precision. A second stage of our investigation involved explaining the profile of the column shafts by a construction model that takes into account the parameters recommended by Vitruvius and design methods such as those that can be found in the construction drawings discovered at Didyma. Our analysis shows that the design principles of the portico’s columns can be successfully reconstructed, and has led to the surpris- ing result that at least two different variants of a simple circle construction were used. Finally, we have been able to deduce from the distribution of the different profile types among the columns that the final profiles were designed and executed in Rome. Introduction design could reach a considerable degree of complexity. The shafts of the Pantheon’s portico columns are com- For example, Stevens believed that the Pantheon’s por- posed of granite monoliths, forty Roman feet tall, which tico columns exhibit a profile that is based on two tan- were excavated from two Egyptian quarries. -

Architectural Product Catalog

TURNCRAFT ARCHITECTURAL PRODUCT CATALOG 2005 A History of Architectural Excellence So many architects and builders The making select Turncraft Architectural Columns of Turncraft because they feature thoughtful Architectural product design, fi ne workmanship, columns is an superior assembly, precision turning exacting process. and fl uting, and artful fi nishing. Finger-jointed Round columns may be ordered with or solid staves true architectural entasis in sizes are milled to consistent with the classic proportions the required of the Greek Doric, Tuscan, Roman dimensions, Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian Orders, assembled using or in custom shaft diameters up to the strongest Type-I waterproof glue, 36" and lengths to 30'. They can and then are metal-banded for curing. be smooth surfaced or given dramatic In the computer-controlled lathe, the deep fl uting (with increased stave assembled shaft is turned to the precise thickness) as desired. Greek Doric taper desired, complete with true Columns feature classic edge-to-edge architectural entasis. The top of each fl uting. Square columns and pilasters column is profi led according to the style may be ordered to match (available specifi ed, and the entire column is in tapered or non-tapered and in machine sanded to ensure a smooth various plan styles—see page 14). fi nish. Flutes are milled at precisely Non-tapered cylinders are available for determined intervals and depths, always INTRODUCTION use in casework, radius wall corners, ending in full half-rounds at the top and and contemporary applications. bottom (except on Greek Doric). Each column, regardless of size, is visually inspected, any defects are corrected, and then it is fi nish sanded. -

The Diminution of the Classical Column: Visual Sensibility In

David A. Vila The Diminution of the Classical Column: Domini Visual Sensibility in Antiquity and the Renaissance David Vila Domini looks at the recommendations regarding optical adjustment of the columnar diminution in the architectural treatises of Vitruvius, Alberti, and Palladio. He examines the variation in diminution of column thickness according to the height of the column, and its implications for our understanding of the various practices with regard both to columnar proportion and visual sensibility in Antiquity and the Renaissance. He also examines possible sources for the methods by which the ratios of column height to diameter were derived. Introduction 1 Writing some time around the 1450s [Grayson 1960], Alberti composed his ten-book treatise on architecture De re aedificatoria, basing it largely on the ancient Roman tract De architectura [Krautheimer 1963], which its author, Vitruvius, dedicated to the emperor Augustus. Alberti and his contemporaries found Vitruvius’s text inelegantly written, often obscure and in some passages entirely unintelligible.2 The widespread use of Greek terms for things that were otherwise nameless in Augustan Latin confounded the efforts of the humanists trying to make sense of the only text on architecture that had survived from the antiquity they had so much come to admire. In his attempt to remedy these linguistic problems, Alberti was forced to introduce neologisms in order to express ideas for which, until then, there were no words in Latin.3 But the difficulties were by no means exclusively linguistic, and constitute an indication of the very different understanding that Roman Antiquity and the Early Renaissance had of architecture. -

Me'morchilik Asoslari

M.MUXAMEDOVA ME’MORCHILIK ASOSLARI TOSHKENT 0 ‘ZBEKIST0N RESPUBLIKASI OLIY VA 0 ‘RTA MAXSUS TA’LIM VAZIRLIGI M.MUXAMEDOVA ME’MORCHILIK ASOSLARI O ‘zbekiston Respublikctsi Oliy va о ‘rta maxsus ta ’lim vazirligi tomonidan о ‘quv qo ‘llanma sifatida tavsiya etilgan UO‘K: 72.01(075.8) K BK 85.il М 96 М 96 M.Muxamedova. Me’morchilik asoslari. -Т.: «Fan va texnologiya», 2018,296 Bet. ISBN 978-9943-11-927-7 Mazkur o‘quv qoilanma me’morchilikning estetik talaBlari, texnik mukam- malligi, Binolar klassifikatsiyasi, asosiy soha va turlari, Binolar konstruksiyasi, me’morchilikning rivojlanish an’analari, yangi tipdagi binolaming funksionalligi va konstruktiv mustahkamligi Bilimlarini o‘zlashtirishga yo'naltiriladi. “Me’morchilik asoslari” o‘quv qoilanmasi mazmuniga yetakchi xorijiy oliy o‘quv yurtlarida ishlaB chiqilgan ilmiy qoilanmalar asosida me’morchilikka oid ilmiy yangiliklar kiritilgan. UshBu o‘quv qo‘llanma doirasida Qadimgi Misr, Old Osiyo, Uzoq Sharq me’morchiligi, Qadimgi Gretsiya iBodatxonalarida qurilish konstruksiyalari va order sistemalari (doriy, ion, korinf), qadimgi Rim ustun-to‘sin sistemasiga yangi konstruksiyalar kiritilishi (kompozit va toskan orderlari) akveduk, amfiteatr, forum, insulalar qurilishi, Vizantiya va ilk xristianlar davri arxitekturasi, roman va gotika usluBi me’morchilik asoslari, Uyg‘onish va Barokko davri shaharsozligining rivojlanish an’analari, klassitsizm va ampir usluBi asoslari, eklektizm, modern, konstruktivizm, funksionalizm usluBlarining zamonaviy usluBiar rivojidagi o‘rni, yangi tipdagi Binolaming funksionalligi va konstruktiv mustahkamligini o‘rganish kaBi mavzular mujassamlashtirilgan. O'quv qo‘llanmaning asosiy dolzarBligi talaBalarga Sharq va G‘arB, umuman olganda jahon me’morchiligining tarixi va nazariyasini o‘rgatish, me’morchilik tarixining tadriji, rivojlanish qonuniyatlarini o‘zlashtirish, turli usluBlaming yuzaga kelishi va shu usluBlar ta’sirida Bunyod etilgan oBidalar me’morchiligini yoritiB Berishdir. -

1 Classical Architectural Vocabulary

Classical Architectural Vocabulary The five classical orders The five orders pictured to the left follow a specific architectural hierarchy. The ascending orders, pictured left to right, are: Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and Composite. The Greeks only used the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian; the Romans added the ‘bookend’ orders of the Tuscan and Composite. In classical architecture the selected architectural order for a building defined not only the columns but also the overall proportions of a building in regards to height. Although most temples used only one order, it was not uncommon in Roman architecture to mix orders on a building. For example, the Colosseum has three stacked orders: Doric on the ground, Ionic on the second level and Corinthian on the upper level. column In classical architecture, a cylindrical support consisting of a base (except in Greek Doric), shaft, and capital. It is a post, pillar or strut that supports a load along its longitudinal axis. The Architecture of A. Palladio in Four Books, Leoni (London) 1742, Book 1, plate 8. Doric order Ionic order Corinthian order The oldest and simplest of the five The classical order originated by the The slenderest and most ornate of the classical orders, developed in Greece in Ionian Greeks, characterized by its capital three Greek orders, characterized by a bell- the 7th century B.C. and later imitated with large volutes (scrolls), a fascinated shaped capital with volutes and two rows by the Romans. The Roman Doric is entablature, continuous frieze, usually of acanthus leaves, and with an elaborate characterized by sturdy proportions, a dentils in the cornice, and by its elegant cornice. -

The Archaic and Classical Greek Temple Callie Williams University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Inquiry: The University of Arkansas Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 7 Article 4 Fall 2006 Development of Gendered Space: The Archaic and Classical Greek Temple Callie Williams University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/inquiry Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Callie (2006) "Development of Gendered Space: The Archaic and Classical Greek Temple," Inquiry: The University of Arkansas Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 7 , Article 4. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/inquiry/vol7/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inquiry: The nivU ersity of Arkansas Undergraduate Research Journal by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Williams: Development of Gendered Space: The Archaic and Classical Greek Te 4 INQUIRY Volume 7 2006 DEVELOPMENT OF GENDERED SPACE: THE ARCHAIC AND CLASSICAL GREEK TEMPLE By Callie Williams . Program in Architectural Studtes Faculty Mentor: Dr. Kim Sexton Department of Architecture view specific forms of architectural space through the Greek Abstract: ideals of gender hierarchy .. Initially, the function and occu~~ncy Throughout the ancient Greek world, temples marked the ofcertain typical spaces created structures with inherentcondiU?ns landscape as a sign of Greek civilization. Although Greek of internal and external space. Greek ideals oflived space- I.e., temples hare been examined, described, and catalogued space lived directly through associated images an~ symbols - scientifically since archaeology came ofage in the 18'h century, would have influenced the design of both domestic (e.g., the the question oftlzeircultural significance in their original Greek Greek house or oikos) and public venues\e.g., the agora).' The context has vet to be fully answered. -

Architecture Vocabulary

Art & Architecture Student Handout Architecture Vocabulary Arcade: a succession of arches supported on columns. An arcade can be free-standing covered passage or attached to a wall, as seen on the right. Arch: the curved support of a building or doorway. The tops of the arches can be curved, semicircular, pointed, etc. Architrave: the lowest part of the entablature that sits directly on the capitals (tops) of the columns. Capital: the top portion of a column. In classical architecture, the architectural order is usually identified by design of the capital (Doric, Ionic, or Corinthian). Classical: of or pertaining to Classicism. See Classicism. Classicism: a preference or regard for the principles of Greek and Roman art and architecture. Common classicizing architecture is a sense of balance, proportion, and “ideal” beauty. Column: an upright post, usually square, round, or rectangular (an example can be seen on the left). It can be used as a support or attached to a wall for decoration. In classical architecture, columns are composed of a capital, shaft, and a base (except in the Doric order). Cornice: the rectangular band above the frieze, below the pediment. Dome: a half-sphere curvature constructed on a circular base, as seen on the right. Entablature: the upper portion of an order, it includes the architrave, frieze and cornice. Frieze: the wide rectangular section on the entablature, above the architrave and below the cornice. In the Doric order, the frieze is often decorated with triglyphs (altering tablets of vertical groves) and the plain, rectangular bands spaced between the triglyphs (called metopes). Order: an ancient style of architecture. -

Exploring Modernity in the Architraves and Ceilings at the Mnesiklean Propylaia Tasos Tanoulas

e a c er a a e or e Nouvelle histoire de la construction sous la direction de Roberto Gargiani Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes L'auteur et l'editeur remercient l'Ecole polytechnique federale de Lausanne pour le soutien apporte a la publication de cet ouvrage. La collection «Architecture Essais» est dirigee par 1es professeurs Jacques Lucan et Luca Orte11i La colonne Nouvelle histoire de la construction Roberto Gorgioni (sous 10 direction de) Composition, non-composition Architecture et theories, X1X'-XX' siecles Jacques Lucan Histoire de I'architecture moderne Structure et revetement Giovanni Fanelli et Roberto Gargiani Enseignement d'un temple egyptien Conception architectonique du temple d'Athor aDendara Pierre Zignani Graphisme et mise en page: antidote [www.antidote-design.ch). Lausanne Couverture: L. Skid more, N. A. Owings, J. O. Merrill/SOM, Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1954-1962. Dining hall en construction [photo Stewarts Commercial Photographers. Courtesy Special Collections, Pikes Peak Library District, negative #5-3) Traduction en fran<;ais: Marie-Christine Lehmann [textes de Salvatore Aprea, Maria Chiara Barone, Antonio Becchi, Gianluca Belli, Alberto Bologna, Massimo Bulgarelli, Antonio Burgos Nunez, Vittorio da Caiano, Giulia Chemolli, Giovanni Di Pasquale, Francesco Di Teodoro, Roberto Gargiani, Jean-Pierre Goguet, Albert Guettard, Riccardo Gulli, Tullia lori, Daniel Jeanneret, Louis Jeanneret, Charles Lafaye, Beatrice Lampariello, Antoine de Maillet, Michele Messeri, Emanuela Montelli, Marc Nollet, Pier Nicola Pagliara, Michael Petzet, Mario Piana, Marco Pogacnik, Sergio Poretti, Francesco Quinterio, Bruno Reichlin, Nicola Rizzi, Anna Rosellini, Giampiero Sanguigni, Hermann Schlimme, Philipp Speiser, Claude Tibieres, Valerio Varano, Etienne Vignon et Robin Wimmel). Recueil de textes edites sous la direction du Laboratoire de Theorie et d'Histoire de I'Architecture 3: Roberto Gargiani, Salvatore Aprea, Maria Chiara Barone, Giulia Chemolli, Beatrice Lampariello, Marie-Christine Lehmann, Khue Tran. -

January 1899

JUrljitrrtttral VOL. VIII. JANUARY-MARCH, 1899. No. 3. THE "SKY-SCRAPER" UP TO DATE. is strange that the solution of a building problem so new as IT that presented by the steel-framed tall building should have apparently so largely ceased to be experimental. The Ameri- can architect is a good deal fonder than his co-worker in other coun- tries of all he is no means so much inclined to proving things ; by hold fast that which is good. On the contrary, he is still altogether too much disposed rather to vindicate his own "originality" than to essay the task, at once more modest and more difficult of "shining with new gracefulness through old forms." Of course his origin- ality will be less crude, and more truly original, in proportion to his education, meaning both his knowledge and his discipline. Nothing can be more depressing than the undertaking to do "something new" by a man who is unaware what has already been done, or who has not learned how it is done. When, within a quarter of a century, the practicable height of commercial buildings has been raised, by successive movements and successive inventions, from five stories to twenty-five, we should expect, given the preference for originality that is born in the American architect, and the absolute necessity for originality that has been thrust upon him by these new mechanical devices, some very wild work, indeed, much wilder than we have had. What nobody could have expected, when the elevator came in to double the practicable height of commercial buildings, and even less when the steel-framed construction came in again to double the height made practicable by the elevator alone, is what has actually happened, and that is a consensus upon a new architectural type.