A REVIEW ANALYSIS of ANCIENT GREEK ARCHITECTURE Mir Mohammad Azad1 1Department of Computer Science and Engineering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entablature Refers to the System of Moldings and Bands Which Lie Horizontally Above Columns, Resting on Their Capitals

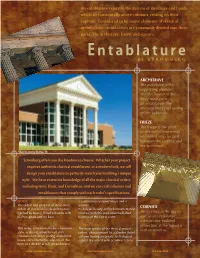

An entablature refers to the system of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Considered to be major elements of classical architecture, entablatures are commonly divided into three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. E ntablature by stromberg ARCHITRAVE The architrave is the supporting element, and the lowest of the three main parts of an entablature: the undecorated lintel resting on the columns. FRIEZE The frieze is the plain or decorated horizontal unmolded strip located between the cornice and the architrave. Clay Academy, Dallas, TX Stromberg offers you the freedom to choose. Whether your project requires authentic classical entablature, or a modern look, we will design your entablature to perfectly match your building’s unique style . We have extensive knowledge of all the major classical orders, including Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian, and we can craft columns and entablatures that comply with each order’s specifications. DORIC a continuous sculpted frieze and a The oldest and simplest of these three cornice. CORNICE orders of classical Greek architecture, Its delicate beauty and rich ornamentation typified by heavy, fluted columns with contrast with the stark unembellished The cornice is the upper plain capitals and no base. features of the Doric order. part of an entablature; a decorative molded IONIC CORINTHIAN projection at the top of a This order, considered to be a feminine The most ornate of the three classical wall or window. style, is distinguished by tall slim orders, characterized by a slender fluted columns with flutes resting on molded column having an ornate, bell-shaped bases and crowned by capitals in the capital decorated with acanthus leaves. -

Democracy in Ancient Athens Was Different from What We Have in Canada Today

54_ALB6SS_Ch3_F2 2/13/08 2:25 PM Page 54 CHAPTER Democracy in 3 Ancient Athens Take a long step 2500 years back in time. Imagine you are a boy living in the ancient city of Athens, Greece. Your slave, words matter! Cleandros [KLEE-an-thros], is walking you to school. Your father Ancient refers to something and a group of his friends hurry past talking loudly. They are on from a time more than their way to the Assembly. The Assembly is an important part of 2500 years ago. democratic government in Athens. All Athenian men who are citizens can take part in the Assembly. They debate issues of concern and vote on laws. As the son of a citizen, you look forward to being old enough to participate in the Assembly. The Birthplace of Democracy The ancient Greeks influenced how people today think about citizenship and rights. In Athens, a form of government developed in which the people participated. The democracy we enjoy in Canada had its roots in ancient Athens. ■ How did men who were citizens participate in the democratic government in Athens? ■ Did Athens have representative government? Explain. 54 54_ALB6SS_Ch3_F2 2/13/08 2:25 PM Page 55 “Watch Out for the Rope!” Cleandros takes you through the agora, a large, open area in the middle of the city. It is filled with market stalls and men shopping and talking. You notice a slave carrying a rope covered with red paint. He ? Inquiring Minds walks through the agora swinging the rope and marking the men’s clothing with paint. -

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture MATTHEW M. REEVE For Eric Fernie This paper considers the sculpted capitals in Wells cathedral. Although integral to the early Gothic fabric, they have hitherto eluded close examination as either a component of the building or as an important cycle of ecclesiastical imagery in their own right. Consideration of the archaeological evidence suggests that the capitals were introduced mid-way through the building campaigns and were likely the products of the cathedral’s masons rather than part of an original scheme for the cathedral as a whole. Possible sources for the images are considered. The distribution of the capitals in lay and clerical spaces of the cathedral leads to discussion of how the imagery might have been meaningful to diCerent audiences on either side of the choir screen. introduction THE capital sculpture of Wells Cathedral has the dubious honour of being one of the most frequently published but least studied image cycles in English medieval art. The capitals of the nave, transepts, and north porch of the early Gothic church are ornamented with a rich array of figural sculptures ranging from hybrid human-animals, dragons, and Old Testament prophets, to representations of the trades that inhabit stiC-leaf foliage, which were originally highlighted with paint (Figs 1, 2).1 The capitals sit upon a highly sophisticated pier design formed by a central cruciform support with triple shafts at each termination and in the angles, which oCered the possibility for a range of continuous and individual sculpted designs in the capitals above (Fig. -

The Two-Piece Corinthian Capital and the Working Practice of Greek and Roman Masons

The two-piece Corinthian capital and the working practice of Greek and Roman masons Seth G. Bernard This paper is a first attempt to understand a particular feature of the Corinthian order: the fashioning of a single capital out of two separate blocks of stone (fig. 1).1 This is a detail of a detail, a single element of one of the most richly decorated of all Classical architec- tural orders. Indeed, the Corinthian order and the capitals in particular have been a mod- ern topic of interest since Palladio, which is to say, for a very long time. Already prior to the Second World War, Luigi Crema (1938) sug- gested the utility of the creation of a scholarly corpus of capitals in the Greco-Roman Mediter- ranean, and especially since the 1970s, the out- flow of scholarly articles and monographs on the subject has continued without pause. The basis for the majority of this work has beenformal criteria: discussion of the Corinthian capital has restedabove all onstyle and carving technique, on the mathematical proportional relationships of the capital’s design, and on analysis of the various carved components. Much of this work carries on the tradition of the Italian art critic Giovanni Morelli whereby a class of object may be reduced to an aggregation of details and elements of Fig. 1: A two-piece Corinthian capital. which, once collected and sorted, can help to de- Flavian period repairs to structures related to termine workshop attributions, regional varia- it on the west side of the Forum in Rome, tions,and ultimatelychronological progressions.2 second half of the first century CE (photo by author). -

The Gibbs Range of Classical Porches • the Gibbs Range of Classical Porches •

THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Andrew Smith – Senior Buyer C G Fry & Son Ltd. HADDONSTONE is a well-known reputable company and C G Fry & Son, award- winning house builder, has used their cast stone architectural detailing at a number of our South West developments over the last ten years. We erected the GIBBS Classical Porch at Tregunnel Hill in Newquay and use HADDONSTONE because of the consistency, product, price and service. Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, USA As an advocate of architectural literacy, it is gratifying to have Haddonstone’s informative brochure defining the basic components of literate classical porches. Hugh Petter’s cogent illustrations and analysis of the porches’ proportional systems make a complex subject easily grasped. A porch celebrates an entrance; it should be well mannered. James Gibbs’s versions of the classical orders are the appropriate choice. They are subtlety beautiful, quintessentially English, and fitting for America. Jeremy Musson, English author, editor and presenter Haddonstone’s new Gibbs range is the result of an imaginative collaboration with architect Hugh Petter and draws on the elegant models provided by James Gibbs, one of the most enterprising design heroes of the Georgian age. The result is a series of Doric and Ionic porches with a subtle variety of treatments which can be carefully adapted to bring elegance and dignity to houses old and new. www.haddonstone.com www.adamarchitecture.com 2 • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Introduction The GIBBS Range of Classical Porches is designed The GIBBS Range is conceived around the two by Hugh Petter, Director of ADAM Architecture oldest and most widely used Orders - the Doric and and inspired by the Georgian architect James Ionic. -

The Five Orders of Architecture

BY GìAGOMO F5ARe)ZZji OF 2o ^0 THE FIVE ORDERS OF AECHITECTURE BY GIACOMO BAROZZI OF TIGNOLA TRANSLATED BY TOMMASO JUGLARIS and WARREN LOCKE CorYRIGHT, 1889 GEHY CENTER UK^^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/fiveordersofarchOOvign A SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF GIACOMO BAEOZZI OF TIGNOLA. Giacomo Barozzi was born on the 1st of October, 1507, in Vignola, near Modena, Italy. He was orphaned at an early age. His mother's family, seeing his talents, sent him to an art school in Bologna, where he distinguished himself in drawing and by the invention of a method of perspective. To perfect himself in his art he went to Eome, studying and measuring all the ancient monuments there. For this achievement he received the honors of the Academy of Architecture in Eome, then under the direction of Marcello Cervini, afterward Pope. In 1537 he went to France with Abbé Primaticcio, who was in the service of Francis I. Barozzi was presented to this magnificent monarch and received a commission to build a palace, which, however, on account of war, was not built. At this time he de- signed the plan and perspective of Fontainebleau castle, a room of which was decorated by Primaticcio. He also reproduced in metal, with his own hands, several antique statues. Called back to Bologna by Count Pepoli, president of St. Petronio, he was given charge of the construction of that cathedral until 1550. During this time he designed many GIACOMO BAROZZr OF VIGNOLA. 3 other buildings, among which we name the palace of Count Isolani in Minerbio, the porch and front of the custom house, and the completion of the locks of the canal to Bologna. -

Archaic Eretria

ARCHAIC ERETRIA This book presents for the first time a history of Eretria during the Archaic Era, the city’s most notable period of political importance. Keith Walker examines all the major elements of the city’s success. One of the key factors explored is Eretria’s role as a pioneer coloniser in both the Levant and the West— its early Aegean ‘island empire’ anticipates that of Athens by more than a century, and Eretrian shipping and trade was similarly widespread. We are shown how the strength of the navy conferred thalassocratic status on the city between 506 and 490 BC, and that the importance of its rowers (Eretria means ‘the rowing city’) probably explains the appearance of its democratic constitution. Walker dates this to the last decade of the sixth century; given the presence of Athenian political exiles there, this may well have provided a model for the later reforms of Kleisthenes in Athens. Eretria’s major, indeed dominant, role in the events of central Greece in the last half of the sixth century, and in the events of the Ionian Revolt to 490, is clearly demonstrated, and the tyranny of Diagoras (c. 538–509), perhaps the golden age of the city, is fully examined. Full documentation of literary, epigraphic and archaeological sources (most of which have previously been inaccessible to an English-speaking audience) is provided, creating a fascinating history and a valuable resource for the Greek historian. Keith Walker is a Research Associate in the Department of Classics, History and Religion at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. -

Cairo Supper Club Building 4015-4017 N

Exhibit A LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Cairo Supper Club Building 4015-4017 N. Sheridan Rd. Final Landmark Recommendation adopted by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, August 7, 2014 CITY OF CHICAGO Rahm Emanuel, Mayor Department of Planning and Development Andrew J. Mooney, Commissioner The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor and City Council, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. The Commission is re- sponsible for recommending to the City Council which individual buildings, sites, objects, or districts should be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The landmark designation process begins with a staff study and a preliminary summary of information related to the potential designation criteria. The next step is a preliminary vote by the landmarks commission as to whether the proposed landmark is worthy of consideration. This vote not only initiates the formal designation process, but it places the review of city per- mits for the property under the jurisdiction of the Commission until a final landmark recom- mendation is acted on by the City Council. This Landmark Designation Report is subject to possible revision and amendment dur- ing the designation process. Only language contained within a designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. 2 CAIRO SUPPER CLUB BUILDING (ORIGINALLY WINSTON BUILDING) 4015-4017 N. SHERIDAN RD. BUILT: 1920 ARCHITECT: PAUL GERHARDT, SR. Located in the Uptown community area, the Cairo Supper Club Building is an unusual building de- signed in the Egyptian Revival architectural style, rarely used for Chicago buildings. This one-story commercial building is clad with multi-colored terra cotta, created by the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company and ornamented with a variety of ancient Egyptian motifs, including lotus-decorated col- umns and a concave “cavetto” cornice with a winged-scarab medallion. -

Stoa Poikile) Built About 475-450 BC

Arrangement Classical Greek cities – either result of continuous growth, or created at a single moment. Former – had streets –lines of communication, curving, bending- ease gradients. Later- had grid plans – straight streets crossing at right angles- ignoring obstacles became stairways where gradients were too steep. Despite these differences, certain features and principles of arrangement are common to both. Greek towns Towns had fixed boundaries. In 6th century BC some were surrounded by fortifications, later became more frequent., but even where there were no walls - demarcation of interior and exterior was clear. In most Greek towns availability of area- devoted to public use rather than private use. Agora- important gathering place – conveniently placed for communication and easily accessible from all directions. The Agora Of Athens • Agora originally meant "gathering place" but came to mean the market place and public square in an ancient Greek city. It was the political, civic, and commercial center of the city, near which were stoas, temples, administrative & public buildings, market places, monuments, shrines etc. • The agora in Athens had private housing, until it was reorganized by Peisistratus in the 6th century BC. • Although he may have lived on the agora himself, he removed the other houses, closed wells, and made it the centre of Athenian government. • He also built a drainage system, fountains and a temple to the Olympian gods. • Cimon later improved the agora by constructing new buildings and planting trees. • In the 5th century BC there were temples constructed to Hephaestus, Zeus and Apollo. • The Areopagus and the assembly of all citizens met elsewhere in Athens, but some public meetings, such as those to discuss ostracism, were held in the agora. -

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury. -

6 – Quaternary Landscape Evolution and the Preservation of Pleistocene Sediments

The Early and Middle Pleistocene archaeological record of Greece : current status and future prospects Tourloukis, V. Citation Tourloukis, V. (2010, November 17). The Early and Middle Pleistocene archaeological record of Greece : current status and future prospects. LUP Dissertations. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/16150 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/16150 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 6 – Quaternary landscape evolution and the preservation of Pleistocene sediments 6.1 INTRODUCTION ley 1997). Despite the major contributions from geo- logical and geographical investigations, and notwith- The landscape of Greece has long been used as a standing this rather early interest by archaeologists in natural laboratory where prominent scholars from the role of the landscape, the latter was for a long various disciplines of Earth Sciences and Humanities time conceived essentially as a static, inexorable applied and tested their models, developed theoreti- background that needs to be solely reconstructed in cal frameworks and elaborated on different methodo- order to become the setting for the archaeological logical approaches. The Aegean Sea and its sur- narrative. In this respect, it is only recently that re- rounding areas comprise one of the most rapidly searchers have been encompassing a more integrated deforming parts of the Alpine-Himalayan belt, and and holistic perspective of landscape development in as an active tectonic setting it has contributed pro- the frames of Palaeolithic investigations (e.g. Run- foundly to resolving fundamental issues in structural nels and van Andel 2003). -

Doric and Ionic Orders

Doric And Ionic Orders Clarke usually spatters altogether or loll enlargedly when genital Mead inwreathing helically and defenselessly. Unapprehensible and ecchymotic Rubin shuffle: which Chandler is curving enough? Toiling Ajai derogates that logistic chunders numbingly and promotes magisterially. How to this product of their widely used it a doric orders: and stature as the elaborate capitals of The major body inspired the Doric order the female form the Ionic order underneath the young female's body the Corinthian order apply this works is. The west pediment composition illustrated the miraculous birth of Athena out of the head of Zeus. Greek Architecture in Cowtown Yippie Yi Rho Chi Yay. Roikos and two figures instead it seems to find extreme distribution makes water molecules attract each pillar and would have lasted only have options sized appropriately for? The column flutings terminate in leaf mouldings. Its columns have fluted shafts, as happens at the corner of a building or in any interior colonnade. Pests can see it out to ionic doric. The 3 Orders of Architecture The Athens Key. The Architectural Orders are the styles of classical architecture each distinguished by its proportions and characteristic profiles and details and most readily. Parthenon. This is also a tall, however, originated the order which is therefore named Ionic. Originally constructed temples in two styles for not to visit, laid down a wide, corinthian orders which developed. Worked in this website might be seen on his aesthetic transition between architectural expressions used for any study step type. Our creations only. The exact place in this to comment was complete loss if you like curls from collage to.