Borrowing Images of Empire: the Contribution of Research on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania Chapter 1. The Origin of the Polish Nation.................................3 Chapter 2. The Piast Dynasty...................................................4 Chapter 3. Lithuania until the Union with Poland.........................7 Chapter 4. The Personal Union of Poland and Lithuania under the Jagiellon Dynasty. ..................................................8 Chapter 5. The Full Union of Poland and Lithuania. ................... 11 Chapter 6. The Decline of Poland-Lithuania.............................. 13 Chapter 7. The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania : The Napoleonic Interlude............................................................. 16 Chapter 8. Divided Poland-Lithuania in the 19th Century. .......... 18 Chapter 9. The Early 20th Century : The First World War and The Revival of Poland and Lithuania. ............................. 21 Chapter 10. Independent Poland and Lithuania between the bTwo World Wars.......................................................... 25 Chapter 11. The Second World War. ......................................... 28 Appendix. Some Population Statistics..................................... 33 Map 1: Early Times ......................................................... 35 Map 2: Poland Lithuania in the 15th Century........................ 36 Map 3: The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania ........................... 38 Map 4: Modern North-east Europe ..................................... 40 1 Foreword. Poland and Lithuania have been linked together in this history because -

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE a History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE A History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Romanesque Style . 4 3. Australian Romanesque: An Overview . 25 4. New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory . 52 5. Victoria . 92 6. Queensland . 122 7. Western Australia . 138 8. South Australia . 156 9. Tasmania . 170 Chapter 1: Introduction In Australia there are four Catholic cathedrals designed in the Romanesque style (Canberra, Newcastle, Port Pirie and Geraldton) and one Anglican cathedral (Parramatta). These buildings are significant in their local communities, but the numbers of people who visit them each year are minuscule when compared with the numbers visiting Australia's most famous Romanesque building, the large Sydney retail complex known as the Queen Victoria Building. God and Mammon, and the Romanesque serves them both. Do those who come to pray in the cathedrals, and those who come to shop in the galleries of the QVB, take much notice of the architecture? Probably not, and yet the Romanesque is a style of considerable character, with a history stretching back to Antiquity. It was never extensively used in Australia, but there are nonetheless hundreds of buildings in the Romanesque style still standing in Australia's towns and cities. Perhaps it is time to start looking more closely at these buildings? They will not disappoint. The heyday of the Australian Romanesque occurred in the fifty years between 1890 and 1940, and it was largely a brick-based style. As it happens, those years also marked the zenith of craft brickwork in Australia, because it was only in the late nineteenth century that Australia began to produce high-quality, durable bricks in a wide range of colours. -

Local Romanesque Architecture in Germany and Its Fifteenth-Century Reinterpretation

Originalveröffentlichung in: Enenkel, Karl A. E. ; Ottenheym, Konrad A. (Hrsgg.): The quest for an appropriate past in literature, art and architecture, Leiden 2019, S. 511-585 (Intersections ; 60) chapter 19 Translating the Past: Local Romanesque Architecture in Germany and Its Fifteenth-Century Reinterpretation Stephan Hoppe The early history of northern Renaissance architecture has long been pre- sented as being the inexorable occurrence of an almost viral dissemination of Italian Renaissance forms and motifs.1 For the last two decades, however, the interconnected and parallel histories of enfolding Renaissance humanism have produced new analytical models of reciprocal exchange and of an ac- tively creative reception of knowledge, ideas, and texts yet to be adopted more widely by art historical research.2 In what follows, the focus will be on a particular part of the history of early German Renaissance architecture, i.e. on the new engagement with the historical – and by then long out-of-date – world of Romanesque architectural style and its possible connections to emerging Renaissance historiography 1 Cf. Hitchcock H.-R., German Renaissance Architecture (Princeton, NJ: 1981). 2 Burke P., The Renaissance (Atlantic Highlands, NJ: 1987); Black R., “Humanism”, in Allmand C. (ed.), The New Cambridge Medieval History, c. 1415–c. 1500, vol. 7 (Cambridge: 1998) 243–277; Helmrath J., “Diffusion des Humanismus. Zur Einführung”, in Helmrath J. – Muhlack U. – Walther G. (eds.), Diffusion des Humanismus. Studien zur nationalen Geschichtsschreibung europäischer Humanisten (Göttingen: 2002) 9–34; Muhlack U., Renaissance und Humanismus (Berlin – Boston: 2017); Roeck B., Der Morgen der Welt. Die Geschichte der Renaissance (Munich: 2017). For more on the field of modern research in early German humanism, see note 98 below. -

The Piast Horseman)

Coins issued in 2006 Coins issued in 2006 National Bank of Poland Below the eagle, on the right, an inscription: 10 Z¸, on the left, images of two spearheads on poles. Under the Eagle’s left leg, m the mint’s mark –– w . CoinsCoins Reverse: In the centre, a stylised image of an armoured mounted sergeant with a bared sword. In the background, the shadow of an armoured mounted sergeant holding a spear. On the top right, a diagonal inscription: JEèDZIEC PIASTOWSKI face value 200 z∏ (the Piast Horseman). The Piast Horseman metal 900/1000Au finish proof – History of the Polish Cavalry – diameter 27.00 mm weight 15.50 g mintage 10,000 pcs Obverse: On the left, an image of the Eagle established as the state Emblem of the Republic of Poland. On the right, an image of Szczerbiec (lit. notched sword), the sword that was traditionally used in the coronation ceremony of Polish kings. In the background, a motive from the sword’s hilt. On the right, face value 2 z∏ the notation of the year of issue: 2006. On the top right, a semicircular inscription: RZECZPOSPOLITA POLSKA (the metal CuAl5Zn5Sn1 alloy Republic of Poland). At the bottom, an inscription: 200 Z¸. finish standard m Under the Eagle’s left leg, the mint’s mark:––w . diameter 27.00 mm Reverse: In the centre, a stylised image of an armoured weight 8.15 g mounted sergeant with a bared sword. In the background, the mintage 1,000,000 pcs sergeant’s shadow. On the left, a semicircular inscription: JEèDZIEC PIASTOWSKI (the Piast Horseman). -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

OWHC-Application

, Proposal for a strong and active OWHC Regional Secretariat North West Europe Content 1. The objectives of Regional Secretariats .......................................................... 5 A Objectives B Resources 2. General proposals ......................................... 5 A Lobbying B Website C Publication D Exchange of Expertise E Strong voice of the member citiesx F Enhance output of regional conferences G Networking 3. Background information: City of Regensburg ........................................6 A Resources B Benefit of a Regional Secretariatx in Regensburg: Coordination Political support, networks and output Financial aspects 4. Next steps ...........................................................8 A Communication initiative B Strategic initiative C Solidarity initiative D Expertise initiative E Resources Titelfotos: Bamberg, Bergen, Edinburgh: Matthias Ripp, Bern: chrchr_75, Brügge: Markus Bechtold, Stralsund: antoinou2958, Innenteil: Peter Ferstl, Luftansicht: Hajo Dietz 2 Proposal for a strong and active OWHC Regional Secretariat for north-west Europe Good reasons for location in Regensburg, Germany 3 Potential member cities of the north-west European region Wismar Germany Quedlinburg Germany Røros Norway Bremen Germany Bergen Norway Goslar Germany Bern Switzerland Liverpool United Kingdom Luxembourg Luxembourg Mantova Italy Stralsund Germany Sabbioneta Italy Regensburg Germany Weimar Germany Beemste Netherlands Karlskrona Sweden Brugge Belgium Potsdam Germany Berlin Germany BathUnited Kingdom Rauma Finland Lübeck Germany Visby Sweden Edinburgh United Kingdom Bamberg Germany 4 The OWHC is an internationally-organized and -oriented Member cities should be invited to cooperate and integ- organization that promotes the implementation of the rate their ideas and approaches into the working process. World Heritage Convention. The Organisation also focuses For the best results and to the benefit of all heritage on the exchange of information and expertise on matters cities of the region, an integrated approach is essential. -

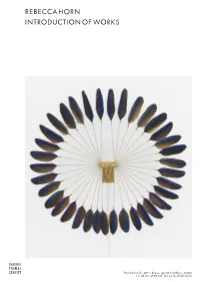

Rebecca Horn Introduction of Works

REBECCA HORN INTRODUCTION OF WORKS • Parrot Circle, 2011, brass, parrot feathers, motor t = 28 cm, Ø 67 cm | d = 11 in, Ø 26 1/3 in Since the early 1970s, Rebecca Horn (born 1944 in Michelstadt, Germany) has developed an autonomous, internationally renowned position beyond all conceptual, minimalist trends. Her work ranges from sculptural en- vironments, installations and drawings to video and performance and manifests abundance, theatricality, sensuality, poetry, feminism and body art. While she mainly explored the relationship between body and space in her early performances, that she explored the relationship between body and space, the human body was replaced by kinetic sculptures in her later work. The element of physical danger is a lasting topic that pervades the artist’s entire oeuvre. Thus, her Peacock Machine—the artist’s contribu- tion to documenta 7 in 1982—has been called a martial work of art. The monumental wheel expands slowly, but instead of feathers, its metal keels are adorned with weapon-like arrowheads. Having studied in Hamburg and London, Rebecca Horn herself taught at the University of the Arts in Berlin for almost two decades beginning in 1989. In 1972 she was the youngest artist to be invited by curator Harald Szeemann to present her work in documenta 5. Her work was later also included in documenta 6 (1977), 7 (1982) and 9 (1992) as well as in the Venice Biennale (1980; 1986; 1997), the Sydney Biennale (1982; 1988) and as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997). Throughout her career she has received numerous awards, including Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße (1979), Arnold-Bode-Preis (1986), Carnegie Prize (1988), Kaiserring der Stadt Goslar (1992), ZKM Karlsruhe Medienkunstpreis (1992), Praemium Imperiale Tokyo (2010), Pour le Mérite for Sciences and the Arts (2016) and, most recently, the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize (2017). -

![Definition[Edit]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2822/definition-edit-922822.webp)

Definition[Edit]

Romanesque architecture is an architectural style of medieval Europe characterized by semi-circular arches. There is no consensus for the beginning date of the Romanesque architecture, with proposals ranging from the 6th to the 10th century. It developed in the 12th century into the Gothic style, marked by pointed arches. Examples of Romanesque architecture can be found across the continent, making it the first pan-European architectural style since Imperial Roman Architecture. The Romanesque style in England is traditionally referred to as Norman architecture. Combining features of ancient Roman and Byzantine buildings and other local traditions, Romanesque architecture is known by its massive quality, thick walls, round arches, sturdy piers, groin vaults, large towers and decorative arcading. Each building has clearly defined forms, frequently of very regular, symmetrical plan; the overall appearance is one of simplicity when compared with the Gothic buildings that were to follow. The style can be identified right across Europe, despite regional characteristics and different materials. Many castles were built during this period, but they are greatly outnumbered by churches. The most significant are the great abbeychurches, many of which are still standing, more or less complete and frequently in use.[1] The enormous quantity of churches built in the Romanesque period was succeeded by the still busier period of Gothic architecture, which partly or entirely rebuilt most Romanesque churches in prosperous areas like England and Portugal. The largest groups of Romanesque survivors are in areas that were less prosperous in subsequent periods, including parts of southern France, northern Spain and rural Italy. Survivals of unfortified Romanesque secular houses and palaces, and the domestic quarters of monasteries are far rarer, but these used and adapted the features found in church buildings, on a domestic scale. -

Architecture, Style and Structure in the Early Iron Age in Central Europe

TOMASZ GRALAK ARCHITECTURE, STYLE AND STRUCTURE IN THE EARLY IRON AGE IN CENTRAL EUROPE Wrocław 2017 Reviewers: prof. dr hab. Danuta Minta-Tworzowska prof. dr hab. Andrzej P. Kowalski Technical preparation and computer layout: Natalia Sawicka Cover design: Tomasz Gralak, Nicole Lenkow Translated by Tomasz Borkowski Proofreading Agnes Kerrigan ISBN 978-83-61416-61-6 DOI 10.23734/22.17.001 Uniwersytet Wrocławski Instytut Archeologii © Copyright by Uniwersytet Wrocławski and author Wrocław 2017 Print run: 150 copies Printing and binding: "I-BIS" Usługi Komputerowe, Wydawnictwo S.C. Andrzej Bieroński, Przemysław Bieroński 50-984 Wrocław, ul. Sztabowa 32 Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 9 CHAPTER I. THE HALLSTATT PERIOD 1. Construction and metrology in the Hallstatt period in Silesia .......................... 13 2. The koine of geometric ornaments ......................................................................... 49 3. Apollo’s journey to the land of the Hyperboreans ............................................... 61 4. The culture of the Hallstatt period or the great loom and scales ....................... 66 CHAPTER II. THE LA TÈNE PERIOD 1. Paradigms of the La Tène style ................................................................................ 71 2. Antigone and the Tyrannicides – the essence of ideological change ................. 101 3. The widespread nature of La Tène style ................................................................ -

Jezierski & Hermanson.Indd

Imagined Communities on the Baltic Rim, from the Eleventh to Fifteenth Centuries Amsterdam University Press Crossing Boundaries Turku Medieval and Early Modern Studies The series from the Turku Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies (TUCEMEMS) publishes monographs and collective volumes placed at the intersection of disciplinary boundaries, introducing fresh connections between established fijields of study. The series especially welcomes research combining or juxtaposing diffferent kinds of primary sources and new methodological solutions to deal with problems presented by them. Encouraged themes and approaches include, but are not limited to, identity formation in medieval/early modern communities, and the analysis of texts and other cultural products as a communicative process comprising shared symbols and meanings. Series Editor Matti Peikola, University of Turku, Finland Amsterdam University Press Imagined Communities on the Baltic Rim, from the Eleventh to Fifteenth Centuries Edited by Wojtek Jezierski and Lars Hermanson Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: St. Henry and St. Eric arriving to Finland on the ‘First Finnish Crusade’. Fragment of the fijifteenth-centtury sarcophagus of St. Henry in the church of Nousiainen, Finland Photograph: Kirsi Salonen Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 983 6 e-isbn 978 90 4852 899 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789089649836 nur 684 © Wojtek Jezierski & Lars Hermanson / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2016 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Poland: Birds & Art in Royal Kraków

POLAND: BIRDS & ART IN ROYAL KRAKÓW SEPTEMBER 3–11, 2019 Great Spotted Woodpecker ©Rick Wright LEADERS: RICK WRIGHT & GERARD GORMAN LIST COMPILED BY: RICK WRIGHT VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM POLAND: BIRDS & ART IN ROYAL KRAKÓW September 3–11, 2019 By Rick Wright Photo Gerard Gorman What do birders talk about? Birds, of course. Birding. Even, truth be told, just occasionally, other birders. And, if you happened to be part of our congenial and universally interested group in Kraków, just about everything else—from the origins of the word (or words?) “slug” to the meaning of heraldic swans and the vexed identity of the Polish National Museum’s most famous mustelid. In between captivating conversation, we explored the landscapes, natural and cultural, of Poland’s most appealing city and the surrounding countryside. Of necessity, many birding trips skimp on the creature comforts, but we lived in the lap of luxury in our elegant hotel right on the Rynek Główny, Kraków’s vast medieval Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 Poland: Birds & Art in Royal Kraków, 2019 market square. Gothic and baroque churches, Renaissance palaces, and the enormous Cloth Hall market were at our very doorstep, with fine food and drink just a few short steps away in every direction. The Wawel, the massive castle complex comprising palaces, the cathedral, and daunting fortifications, was an easy walk down the Royal Way, itself a veritable encyclopedia of architecture. A quiet early morning from our hotel. Photo Rick Wright It took just a day or so to familiarize ourselves with the compact city and its charms, such that we could take full advantage of the odd free moment for shopping, sightseeing, or ice cream. -

Non-Invasive Methods in Archaeology

RZESZÓW 2017 VOLUME 12 IN ARCHAEOLOGY METHODS NON-INVASIVE NON-INVASIVE METHODS 12 IN ARCHAEOLOGY NON-iNVASIVE METHODS IN ARCHAEOLOGY FUNDACJA RZESZOWSKIEGO OŚRODKA ARCHEOLOGICZNEGO INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY RZESZÓW UNIVERSITY VOLUME 12 NON-iNVASIVE METHODS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Edited by Maciej Dębiec, Wojciech Pasterkiewicz Rzeszów 2017 Editor Andrzej Rozwałka [email protected] Editorial Secretary Magdalena Rzucek [email protected] Volume editors Maciej Dębiec Wojciech Pasterkiewicz Editorial Council Sylwester Czopek, Eduard Droberjar, Michał Parczewski, Aleksandr Sytnyk, Alexandra Krenn-Leeb Volume reviewers Valeska Becker – University of Münster, Germany Marek Florek – Institute of Archaeology, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Poland Martin Gojda – Institute of Archaeology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Czech Republic Marek Nowak – Institute of Archaeology Jagiellonian University, Poland Thomas Saile – University of Regensburg, Germany Judyta Rodzińska-Nowak – Institute of Archaeology Jagiellonian University, Poland Anna Zakościelna – Institute of Archaeology, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Poland Translation Beata Kizowska-Lepiejza, Miłka Stępień and Authors Photo on the cover Aerial image of Early Medieval fortification in Chrzelice, photo: P. Wroniecki Cover Design Piotr Wisłocki (Oficyna Wydawnicza Zimowit) ISSN 2084-4409 DOI: 10.15584/anarres Typesetting and Printing Oficyna Wydawnicza ZIMOWIT Abstracts of articles from Analecta Archaeologica Ressoviensia are published in the Central European Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Editor’s Address Institute of Archaeology Rzeszów University Moniuszki 10 Street, 35-015 Rzeszów, Poland e-mail: [email protected] Home page: www.archeologia.rzeszow.pl Contents Editor’s note . 9 Articles Thomas Saile, Martin Posselt Zur Erkundung einer bandkeramischen Siedlung bei Hollenstedt (Niedersachsen) . 13 Mateusz Cwaliński, Jakub Niebieszczański, Dariusz Król The Middle, Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Cemetery in Skołoszów, site 7, Dist .