Lost in Transition? Republican Women's Struggle After Armed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terrorism and Political Violence Who Were The

This article was downloaded by: [University College London] On: 28 July 2014, At: 04:40 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Terrorism and Political Violence Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ftpv20 Who Were the Volunteers? The Shifting Sociological and Operational Profile of 1240 Provisional Irish Republican Army Members Paul Gill a & John Horgan b a Department of Security and Crime Science , University College London , London , UK b International Center for the Study of Terrorism, The Pennsylvania State University, State College , Pennsylvania , USA Published online: 14 Jun 2013. To cite this article: Paul Gill & John Horgan (2013) Who Were the Volunteers? The Shifting Sociological and Operational Profile of 1240 Provisional Irish Republican Army Members, Terrorism and Political Violence, 25:3, 435-456, DOI: 10.1080/09546553.2012.664587 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2012.664587 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Versions of published Taylor & Francis and Routledge Open articles and Taylor & Francis and Routledge Open Select articles posted to institutional or subject repositories or any other third-party website are without warranty from Taylor & Francis of any kind, either expressed or implied, including, but not limited to, warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, or non- infringement. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

Newshound: Daily Northern Ireland News Catalog - Irish News Article

Newshound: Daily Northern Ireland news catalog - Irish News article Bereaved urge Adams — reveal truth on HOME agents This article appears thanks to the Irish News. History (Allison Morris, Irish News) Subscribe to the Irish News NewsoftheIrish The children of a Co Tyrone couple murdered by loyalists have challenged Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams to call on the IRA to reveal publicly what it knows about British agents Book Reviews working in its ranks. & Book Forum Charlie Fox (63) and his wife Tess (53) were shot at their Search / Archive home in Moy, Co Tyrone, in September 1992 by the UVF. Back to 10/96 Mrs Fox was hit in the back. Her husband was shot in the Papers head. Reference Their children spoke out yesterday (Tuesday) after a Sinn Féin 'march for truth' on Sunday which called for collusion between the British state and loyalists to be exposed and at About which Mr Adams said: "Yes, the British recruited, blackmailed, tricked, intimidated and bribed individual republicans into working for them and I think it would be Contact only right to have this dimension of British strategy investigated also." Leading loyalist Laurence George Maguire was convicted in 1994 of directing the UVF gang responsible for murdering Mr and Mrs Fox. A week before the couple's deaths their son Patrick Fox was jailed for 12 years for possession of explosives. He said yesterday that while he welcomed Mr Adams's call for disclosure on British collusion with loyalists, the truth about republican agents must be revealed. "We know now that there were moves towards a ceasefire being made as far back as 1986," he said. -

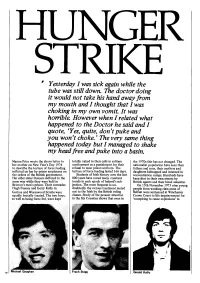

Article on Hungerstrike

" Yesterday I was sick again while the tube was still down. The doctor doing it would not take his hand away [rom my mouth and I thought that I was choking in my own vomit. It was homble. However when I related what happened to the Doctor he said and I quote, 'Yes, quite, don'tpuke and you won't choke. ' The very same thing happened today but I managed to shake my head [ree and puke into a basin. Marian Price wrote the above letter to totaHy naked in their ceHs in solitary the 1970s this has not changed. The her mother on New Year's Day 1974 confinement as a punishment for their nationalist population have seen their to describe the torture of force feeding refusal to wear prison uniform. The fathers and sons, their mothers and inflicted on her by prison employees on torture of force feeding lasted 166 days. daughters kidnapped and interned in the orders of the British government. Students of Irish history over the last concentration camps. Hundreds have Her eIder sister Dolours suffered in the 800 years have noted many constant been shot in their own streets by same way while they were held in trends in each epoch of Ireland's sub• British agents and their hired assassins. Brixton's men's prison. Their comrades jection. The most frequent is un• On 15th November 1973 nine young Hugh Feeney and Gerry KeHy in doubtedly the vicious treatment meted people from working class areas of Gartree and Wormwood Scrubs were out to the Irish by the British ruling Belfast were sentenced at Winchester equally brutally treated. -

The Path to Revolutionary Violence Within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA

The Path to Revolutionary Violence within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA Edward Moran HIS 492: Seminar in History December 17, 2019 Moran 1 The 1960’s was a decade defined by a spirit of activism and advocacy for change among oppressed populations worldwide. While the methods for enacting change varied across nations and peoples, early movements such as that for civil rights in America were often committed to peaceful modes of protest and passive resistance. However, the closing years of the decade and the dawn of the 1970’s saw the patterned global spread of increasingly militant tactics used in situations of political and social unrest. The Weather Underground Organization (WUO) in America and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) in Ireland, two such paramilitaries, comprised young activists previously involved in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association (NICRA) respectively. What caused them to renounce the non-violent methods of the Students for a Democratic Society and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association for the militant tactics of the Weather Underground and Irish Republican Army, respectively? An analysis of contemporary source materials, along with more recent scholarly works, reveals that violent state reactions to more passive forms of demonstration in the United States and Northern Ireland drove peaceful activists toward militancy. In the case of both the Weather Underground and the Provisional Irish Republican Army in the closing years of the 1960s and early years of the 1970s, the bulk of combatants were young people with previous experience in more peaceful campaigns for civil rights and social justice. -

LIST of POSTERS Page 1 of 30

LIST OF POSTERS Page 1 of 30 A hot August night’ feauturing Brush Shiels ‘Oh no, not Drumcree again!’ ‘Sinn Féin women demand their place at Irish peace talks’ ‘We will not be kept down easy, we will not be still’ ‘Why won’t you let my daddy come home?’ 100 years of Trade Unionism - what gains for the working class? 100th anniversary of Eleanor Marx in Derry 11th annual hunger strike commemoration 15 festival de cinema 15th anniversary of hunger strike 15th anniversary of the great Long Kesh escape 1690. Educate not celebrate 1969 - Nationalist rights did not exist 1969, RUC help Orange mob rule 1970s Falls Curfew, March and Rally 1980 Hunger Strike anniversary talk 1980 Hunger-Strikers, 1990 political hostages 1981 - 1991, H-block martyrs 1981 H-block hunger-strike 1981 hunger strikes, 1991 political hostages 1995 Green Ink Irish Book Fair 1996 - the Nationalist nightmare continues 20 years of death squads. Disband the murderers 200,000 votes for Sinn Féin is a mandate 21st annual volunteer Tom Smith commemoration 22 years in English jails 25 years - time to go! Ireland - a bright new dawn of hope and peace 25 years too long 25th anniversary of internment dividedsociety.org LIST OF POSTERS Page 2 of 30 25th anniversary of the introduction of British troops 27th anniversary of internment march and rally 5 reasons to ban plastic bullets 5 years for possessing a poster 50th anniversary - Vol. Tom Williams 6 Chontae 6 Counties = Orange state 75th anniversary of Easter Rising 75th anniversary of the first Dáil Éireann A guide to Irish history -

La Mon Atrocity Remembered a Memorial Service Has Been Held In

::: u.tv ::: NEWS Body found at Grand Canal SUNDAY Confidential files found at roadside 17/02/2008 18:05:01 Jobs boost for Cork Two 'critical' after attack La Mon atrocity remembered War of words 09:39 A memorial service has been held in Belfast to 09:20 New crime crackdown launched mark the 30th anniversary of the La Mon hotel Atrocity is remembered Man held after 'sex attack' bombing. La Mon atrocity remembered Relatives of the 12 people killed in the 1978 IRA atrocity gathered at Two held after Moira assault Castlereagh Council offices this afternoon for a service of remembrance Three held after drugs find led by the Rev David McIlveen. Limavady fire is 'suspicious' Man dies after Galway crash The DUP`s Irish Robinson and Jimmy Spratt were also among those Brendan Hughes has died attending the service today. Petrol bomb attack in Cullybackey Charge after Belfast death Disruption to Dublin Airport flights The event follows criticism of the DUP from some of the La Mon families who have accused Ian Paisley of letting victims down by going into Cannabis seeds found in Moy government with Sinn Fein. Man dies after Carlow RTC Charges after Portadown attack Two held after drugs seizure More than 400 people were attending a dinner dance in La Mon, when the IRA incendiary device went off. Man stabbed in Sligo Man 'critical' after Dublin assault Bluetongue confirmed in NI A wreath was laid at the La Mon garden in the council grounds today in Donegal murder victim laid to rest memory of the seven women and five men who were killed in one of the worst attacks of the Troubles. -

Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980S Irish Theatre

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Provoking performance: challenging the people, the state and the patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Author(s) O'Beirne, Patricia Publication Date 2018-08-28 Publisher NUI Galway Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/14942 Downloaded 2021-09-27T14:54:59Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Candidate: Patricia O’Beirne Supervisor: Dr. Ian Walsh School: School of Humanities Discipline: Drama and Theatre Studies Institution: National University of Ireland, Galway Submission Date: August 2018 Summary of Contents: Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre This thesis offers new perspectives and knowledge to the discipline of Irish theatre studies and historiography and addresses an overlooked period of Irish theatre. It aims to investigate playwriting and theatre-making in the Republic of Ireland during the 1980s. Theatre’s response to failures of the Irish state, to the civil war in Northern Ireland, and to feminist and working-class concerns are explored in this thesis; it is as much an exploration of the 1980s as it is of plays and playwrights during the decade. As identified by a literature review, scholarly and critical attention during the 1980s was drawn towards Northern Ireland where playwrights were engaging directly with the conflict in Northern Ireland. This means that proportionally the work of many playwrights in the Republic remains unexamined and unpublished. -

Double Blind

Double Blind The untold story of how British intelligence infiltrated and undermined the IRA Matthew Teague, The Atlantic, April 2006 Issue https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2006/04/double-blind/304710/ I first met the man now called Kevin Fulton in London, on Platform 13 at Victoria Station. We almost missed each other in the crowd; he didn’t look at all like a terrorist. He stood with his feet together, a short and round man with a kind face, fair hair, and blue eyes. He might have been an Irish grammar-school teacher, not an IRA bomber or a British spy in hiding. Both of which he was. Fulton had agreed to meet only after an exchange of messages through an intermediary. Now, as we talked on the platform, he paced back and forth, scanning the faces of passersby. He checked the time, then checked it again. He spoke in an almost impenetrable brogue, and each time I leaned in to understand him, he leaned back, suspicious. He fidgeted with several mobile phones, one devoted to each of his lives. “I’m just cautious,” he said. He lives in London now, but his wife remains in Northern Ireland. He rarely goes out, for fear of bumping into the wrong person, and so leads a life of utter isolation, a forty-five-year-old man with a lot on his mind. During the next few months, Fulton and I met several times on Platform 13. Over time his jitters settled, his speech loosened, and his past tumbled out: his rise and fall in the Irish Republican Army, his deeds and misdeeds, his loyalties and betrayals. -

THE APPARATUS of IMPUNITY? Human Rights Violations and the Northern Ireland Conflict: a Narrative of Official Limitations on Post-Agreement Investigative Mechanisms

THE APPARATUS OF IMPUNITY? Human rights violations and the Northern Ireland conflict: a narrative of official limitations on post-Agreement investigative mechanisms Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) © Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The material may be reproduced, free of charge, in any format or medium without specific permission, provided the reproduction is not for financial or material gain.The material must be reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. If the material is to be republished or issued to others, acknowledgement must be given to its source, copyright status, and date of publication. This publication is available on our website. CAJ Committee on the Administration of Justice 2nd Floor, Sturgen Building 9-15 Queen Street Belfast BT1 6EA Tel: 028 9031 6000 Fax: 028 9031 4583 [email protected] www.caj.org.uk ISBN 978 1 873285 94 7 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) THE APPARATUS OF IMPUNITY? Human rights violations and the Northern Ireland conflict: a narrative of official limitations on post-Agreement investigative mechanisms Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) Recent comments from key Council of Europe and UN human rights bodies in relation to existing mechanisms investigating the conflict in Northern Ireland: The absence of any plausible explanation for the failure to collect key evidence at the time when this was possible, and for attempts to even obstruct this process, should be treated with particular vigilance. -

Appendix List of Interviews*

Appendix List of Interviews* Name Date Personal Interview No. 1 29 August 2000 Personal Interview No. 2 12 September 2000 Personal Interview No. 3 18 September 2000 Personal Interview No. 4 6 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 5 16 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 6 17 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 7 18 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 8: Oonagh Marron (A) 17 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 9: Oonagh Marron (B) 23 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 10: Helena Schlindwein 28 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 11 30 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 12 1 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 13 1 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 14: Claire Hackett 7 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 15: Meta Auden 15 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 16 1 June 2000 Personal Interview Maggie Feeley 30 August 2005 Personal Interview No. 18 4 August 2009 Personal Interview No. 19: Marie Mulholland 27 August 2009 Personal Interview No. 20 3 February 2010 Personal Interview No. 21A (joint interview) 23 February 2010 Personal Interview No. 21B (joint interview) 23 February 2010 * Locations are omitted from this list so as to preserve the identity of the respondents. 203 Notes 1 Introduction: Rethinking Women and Nationalism 1 . I will return to this argument in a subsequent section dedicated to women’s victimisation as ‘women as reproducers’ of the nation. See also, Beverly Allen, Rape Warfare: The Hidden Genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1996); Alexandra Stiglmayer, (ed.), Mass Rape: The War Against Women in Bosnia- Herzegovina (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1994); Carolyn Nordstrom, Fieldwork Under Fire: Contemporary Studies of Violence and Survival (Berkeley: University of California, 1995); Jill Benderly, ‘Rape, feminism, and nationalism in the war in Yugoslav successor states’ in Lois West, ed., Feminist Nationalism (London and New Tork: Routledge, 1997); Cynthia Enloe, ‘When soldiers rape’ in Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women’s Lives (Berkeley: University of California, 2000). -

Irish Political Studies the Art and Effect of Political Lying in Northern Ireland

This article was downloaded by: [The Library at Queen's University] On: 06 May 2015, At: 09:02 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Irish Political Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fips20 The Art and Effect of Political Lying in Northern Ireland Arthur Aughey Published online: 08 Sep 2010. To cite this article: Arthur Aughey (2002) The Art and Effect of Political Lying in Northern Ireland, Irish Political Studies, 17:2, 1-16, DOI: 10.1080/714003199 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/714003199 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.