1962: Photography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kodak-History.Pdf

. • lr _; rj / EASTMAN KODAK COMPANY A Brief History In 1875, the art of photography was about a half a century old. It was still a cumbersome chore practiced primarily by studio professionals and a few ardent amateurs who were challenged by the difficulties of making photographs. About 1877, George Eastman, a young bank clerk in Roch ester, New York, began to plan for a vacation in the Caribbean. A friend suggested that he would do well to take along a photographic outfit and record his travels. The "outfit," Eastman discovered, was really a cartload of equipment that included a lighttight tent, among many other items. Indeed, field pho tography required an individual who was part chemist, part tradesman, and part contortionist, for with "wet" plates there was preparation immediately before exposure, and develop ment immediately thereafter-wherever one might be . Eastman decided that something was very inadequate about this system. Giving up his proposed trip, he began to study photography. At that juncture, a fascinating sequence of events began. They led to the formation of Eastman Kodak Company. George Eastman made A New Idea ... this self-portrait with Before long, Eastman read of a new kind of photographic an experimental film. plate that had appeared in Europe and England. This was the dry plate-a plate that could be prepared and put aside for later use, thereby eliminating the necessity for tents and field processing paraphernalia. The idea appealed to him. Working at night in his mother's kitchen, he began to experiment with the making of dry plates. -

HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Cameras

· V 1965 SPRING SUMMER KODAK PRE·MI MCATALOG HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Cameras ... No. C 11 SMP HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Flasholder For "bounce-back" offers where initial offer was the Hawkeye Instamatic camera. Creates additional sales, gives promotion longer life. Flash holder attaches eas ily to top of Hawkeye Instamatic camera. Makes in door snapshots as easy to take as outdoor ones. No. ASS HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Camera A great self-liquidator. Handsomely styled in teal green and ivory with bright aluminum trim. Hawkeye Instamatic camera laads instantly with No. CS8MP HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Field Case film in handy, drop-in Kodapak cartridges. Takes black-and-white and Perfect choice for "bounce-back" offers where initial color snapshots, and color slides. Extremely easy to use .• • gives en offer was the Hawkeye Instamatic camera or Hawkeye joyment to the entire family. Available in mailer pack. May be person Instamatic F camera. Handsome black simulated alized on special orders with company identification on the camera, either leather case protects camera from dirt and scratches, removable or affixed permanently. facilitates carrying. Supplied flat in mailing envelope. 3 STEPS 1. Dealer load to your customers. TO ORGANIZING Whether your customer operates a supe- market, drug store, service station, or 0 eo" retail business, be sure he is stocked the products your promotion will feo 'eo. AN EFFECTIVE Accomplish this dealer-loading step by fering your customer additional ince .. to stock your product. SELF -LIQUIDATOR For example: With the purchase of • cases of your product, your custo mer ~ ceives a free in-store display and a HA PROMOTION EYE INSTAMATIC F Outfit. -

Corporate Archives and the Eastman Kodak Company

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 5-2018 Making History Work: Corporate Archives and the Eastman Kodak Company Emily King Rochester Institute of Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation King, Emily, "Making History Work: Corporate Archives and the Eastman Kodak Company" (2018). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS MAKING HISTORY WORK: CORPORATE ARCHIVES AND THE EASTMAN KODAK COMPANY A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE BACHELOR OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN MUSEUM STUDIES DEPARTMENTS OF PERFORMING ARTS AND VISUAL CULTURE AND HISTORY BY EMILY KING APRIL 2018 Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................................1 I. Literature Review.........................................................................................................................2 A. An Historical Perspective................................................................................................2 B. Advocating for Business Archives..................................................................................6 C. Best Practices in the Field -

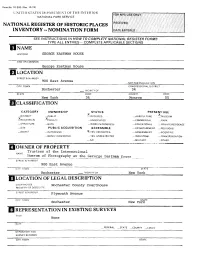

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DhPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC GEORGE EASTMAN HOUSE AND'OR COMMON George Eastman House LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 900 East Avenue _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Rochester . VICINITY OF 34 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New York 36 Monroe 55 ^CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY QWNERSHiP STATUS PRESENT USE X V ^DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM 2ESUILD!NG\S} ^PRIVATE —.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _PARK _-STRUCTURE __BOTH __WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _.OBJECT _IN PROCESS ?-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY __OTHER [OWNER OF PROPERTY Trustees of the International NAME Museum of Photography at the Gerorge EastmQn House STREEF& NUMBER 900 East Avenue STATE Rochester VICINITY OF New York LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. Rochester County Courthouse REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC STREET & NUMBER Plymouth Avenue STATE CITY. TOWN Rochester New York REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None DATE .FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY .__LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD —RUINS ^.ALTERED —MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Eastman residence probably reflects as much of the inventor's desires as it does the architect's design. A local architect, J. Foster Warner, supervised the construction of the house but Eastman chose the design and insisted upon the inclusion of many details which he had observed and photographed in other houses. -

KODAK MILESTONES 1879 - Eastman Invented an Emulsion-Coating Machine Which Enabled Him to Mass- Produce Photographic Dry Plates

KODAK MILESTONES 1879 - Eastman invented an emulsion-coating machine which enabled him to mass- produce photographic dry plates. 1880 - Eastman began commercial production of dry plates in a rented loft of a building in Rochester, N.Y. 1881 - In January, Eastman and Henry A. Strong (a family friend and buggy-whip manufacturer) formed a partnership known as the Eastman Dry Plate Company. ♦ In September, Eastman quit his job as a bank clerk to devote his full time to the business. 1883 - The Eastman Dry Plate Company completed transfer of operations to a four- story building at what is now 343 State Street, Rochester, NY, the company's worldwide headquarters. 1884 - The business was changed from a partnership to a $200,000 corporation with 14 shareowners when the Eastman Dry Plate and Film Company was formed. ♦ EASTMAN Negative Paper was introduced. ♦ Eastman and William H. Walker, an associate, invented a roll holder for negative papers. 1885 - EASTMAN American Film was introduced - the first transparent photographic "film" as we know it today. ♦ The company opened a wholesale office in London, England. 1886 - George Eastman became one of the first American industrialists to employ a full- time research scientist to aid in the commercialization of a flexible, transparent film base. 1888 - The name "Kodak" was born and the KODAK camera was placed on the market, with the slogan, "You press the button - we do the rest." This was the birth of snapshot photography, as millions of amateur picture-takers know it today. 1889 - The first commercial transparent roll film, perfected by Eastman and his research chemist, was put on the market. -

The Rise and Fall of Eastman Kodak: Looking Through Kodachrome Colored Glasses

American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR) 2020 American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR) e-ISSN : 2378-703X Volume-4, Issue-12, pp-219-224 www.ajhssr.com Research Paper Open Access The Rise and Fall of Eastman Kodak: Looking Through Kodachrome Colored Glasses Peter A. Stanwick1, Sarah D. Stanwick2 1Department of Management/Auburn University, United States 2School of Accountancy/Auburn University, United States Corresponding Author: Peter A. Stanwick ABSTRACT:Eastman Kodak is a truly iconic American brand. Established at the end of the nineteenth century, Kodak revolutionized the photography industry by letting every consumer have the ability to develop their own personal pictures at a low cost. However, Kodak stubbornly continued to embrace film photography long after consumers had shifted to digital based photography. In 2012, Kodak was forced to declare Chapter 11 bankruptcy due to its inability to generate positive cash flows in an industry which had moved beyond film photography. In an attempt to reverse its declining financial performance, Kodak introduced products such as the revised Super 8 camera, a smart phone, cryptocurrency, bitcoin mining and the development of chemicals for generic drugs. All of these new product introductions have failed or have been suspended. In addition, there are questions as to whether the real motive of these “new” product innovations was to be used to aid in the financial recovery of Kodak or were these actions based on manipulating Kodak‟s stock price for the personal gain of its executives. This article concludes by asking the question whether or not it is now time for Kodak to permanently close down its operations. -

Kodak Magazine; Vol. 17; No. 3; June 1938

"LOW TIDE/ ' by Ronald E. Karley, of Camera Works. This picture, taken along the Thames, was among 229 hung in the Seventeenth Annual Spring Exhibition of the Kodak Camera Club of Rochester. Further pictures from the exhibition will be found on pages 8 and 9 , and inside the back cover IN THIS ISSUE George Eastman: Portrait of a Pioneer Page 1 The Editor's Page Page 10 From errand boy to photography's knight-erra nt Fifty years after; many- and costly Memorable Meeting at Kodak P age 2 Highlights of Kodak International Exhibit Page 11 A picture of two famous inventors Fresh from its tour of sixteen cities The Oldest Stockholder; Oldest Employee Page 3 Activities Calendar Page 11 They tell of the early Kodak days The dates and the data Panorama Page 4 Out of the Hat Page 12 From our own watchtower Cartoonist; sailoT; old-timer Take a Trip Through Kodak Tracts Page 5 Market Day in Erongaricuaro Page 13 A look at the Company's home-building projects A picture from old M exico Advertising's Part in Kodak Progress Page 6 A Year's Roll of Retired Kodak Employees Page 15 Wheels hum when their products are wanted From Rochester, Chicago, and Los Angele.s Pictures from the Annual Spring Exhibition Page 8 "Along the Potomac" Inside Back Cover ... of the Kodak Camera Club of Rochester In the photograph gallery Copyright , 1938 Kodak C ompa ny Volume 17 JUNE 1938 Numbe r 3 George Eastman: Portrait of a Pioneer How an Errand Boy Became The at the bank went on as usual. -

Behind the Lens: Photography in the Pikes Peak Region

Behind the Lens: Photography in the Pikes Peak Region During the nineteenth century rapid advances in photography and the development of the west went hand in hand. As the science and practice of photography grew more efficient and less expensive, Americans who might never travel west of the Mississippi River could view an astounding array of breathtaking images of mountains, canyons, and vast open spaces from the comfort of their homes. Photographs of the seemingly endless landscape and natural resources helped spur western emigration and finance railroads, town companies and businesses. It also changed the way Americans remembered themselves. Historian Martha Sandweiss notes that for Americans moving west, “photographs provided a way for these immigrants to maintain visual ties to the families and places they had left behind.” Since 1839 when the invention of the first “permanent photograph” was announced, photography has been a rapidly and dynamically evolving mix of the scientific and artistic. The inventors of photography are generally considered to be Joseph Nie’pce, Jacques Louis Mande’ Daguerre, and William Henry Fox Talbot, all of whom were both artists and chemists. The chemical and material processes of photography have dictated how the medium would be used and by whom. The stylistic and artistic conventions of photography have also evolved over the course of the past 175 years according to the tastes of both the producers and consumers of images. The varied ways people use photography: as memento of family and friends, container of personal memory, instrument of scientific inquiry, entertainment, documentation and evidence, promotion, tool of surveillance or an object of art – changes over time according to society’s needs and desires. -

George Eastman at Home by Elizabeth Brayer

ROCHESTER HISTORY Edited by Ruth Rosenberg-Naparsteck City Historian Vol. LIi Winter, 1990 No.1 George Eastman by Elizabeth Brayer Above: George Eastman al/he age of three in 185 7. This miniature ambrolype in a case appears lo be the only surviving early childhood photograph of the person who set the world lo snapping pictures. Cover: George Eastman and an unidentified passenger in his handmade 4 1/2 horsepower Stanley Steamer l..ocomobile about 1900. An early president of the Automobile Club, Eastman "believed that automobiling is destined lo be a great benefit lo this country," and always had five or sir of the /ales/ models in his garage. The Stanley twins who made this "flying teapot, " as the press dubbed ii, also made photographic dry plates. They sold their dry plate business lo Eastman in 1904. ROCHESTER HISTORY, published quarterly by the Rochester Public Library. Address correspondence to City Historian, Rochester Public Library, 115 South Ave., Rochester, NY 14604. Subscriptions to the quarterly Rochester History are $6.00 per year by mail. $4.00 per year to people over 55 years of age and to non-profit institutions and libraries outside of Monroe County. $3.60 per year for orders of 50 or more copies. Foreign subscriptions $10.00. ~ROCHESTER PUBLIC LIBRARY 1989 US ISSN 0035-7413 2 Enstmnn's /rouse in Waterville, New York. On the 100th anniversary of Enslmnn 's birth tir e house was moved to tire grounds of George Eastman House of Plrotogrnplry (as ii wns then en lied.) Twenty-five yen rs later it wns moved to Genesee Country Museum . -

A Chronicle of the Motion Picture Industry a Chronicle of the Motion Picture Industry

A CHRONICLE OF THE MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY A CHRONICLE OF THE MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY INTRODUCTION If you’ve ever taken a still photograph, you’re already acquainted with the essentials of shooting a motion picture image. The biggest diMerence between the two is that the movie camera typically captures twenty-four images each second. Well into the late Nineteenth Century, most images were captured on sensitized glass plates, metal, or heavy paper. Shortly after the invention of 1951 KODAK BROWNIE photography, attempts were already underway to capture and reproduce a Movie Camera moving image. Typically, an array of individual cameras, triggered in rapid succession, captured a series of single exposures on glass plates. These experiments relied on a persistence of vision concept—the eye-brain combination is capable of melding a series of sequential images into a movie. A more practical photographic system had yet to be created. It was George Eastman’s invention of the KODAK Camera, and the flexible film it exposed, that made the movie camera possible. A HISTORY OF CINEMATOGRAPHY Human fascination with the concept of communicating with light and shadows has its roots in antiquity. Aristotle supplied the earliest reference to the camera obscura—sunlight, passing through a small hole, projected an inverted image on the wall of a darkened room. Renaissance artists traced that projected image to create accurate drawings. Gemma Frisius published a drawing of a camera obscura in 1545. Thirteen years later Giovanni Battista della Porta wrote "Magia Naturalis," a book describing the use of a camera obscura with lenses and concave mirrors to project a tableau in a darkened room. -

How Kodak Got Its Name

ow KODAK GO ITS N ME [We are often asked where the name "Kodak" came from or to reveal the story behind its origin . We have printed this account of it to answer such inquiries more fully than a letter could. -Eastman Kodak Company] The word "Kodak" was first registered as a trademark in 1888, having been adopted the year before as the name of a camera that was to make photography everybody's hobby. This first Kodak cam era sold for $25 already loaded with film; and after 100 exposures, it was returned to the factory for the developing and printing of the pictures and the insertion of another roll of film. The cost of the processing and of the new roll of film was $10. The camera made excellent pictures. From that day to this, the Kodak trade mark has been applied to hundreds of products manufactured by Eastman Kodak Company. Partly on this account and partly because the legal profession has always considered it a "model" trade mark-"Kodak" has a kind of fame all its own. Just how the name came into being is known from personal accounts by people "who were there" and through remarks about it made by founder George Eastman himself-either orally to inquirers or in his letters. There has been some fanciful specula tion, from time to time, on how the name was originated. But the plain truth is: George Eastman invented it out of thin air! His most succinct statement in the matter was made to Samuel Crowther of SYSTEM Magazine in 1920: "I devised the name myself . -

Kerrisdale Cameras: Used List

KERRISDALE CAMERAS This used list is used by our staff internally and we post it weekly on our website, usually on Mondays and Thursdays. To Note: Descriptions are abbreviated because they are from our 'back-office' inventory system and meant for internal-use and therefore not fully "user-friendly". Items shown here were in stock on the morning of the report's date. Contact us to check current availability as items may have sold since this report was run. The item in stock may only be available in one of our seven stores. In most cases, we can transfer an item to any of our stores within one to three business days. Items marked "reserve" may be on hold. Please contact us to check availability. Item marked with two asterisks ** indicate that it is an item that regularly comes into stock and may have more than one in stock available. Also, many new items are required to be held for a month before we can sell them, as required by some municipalities' bylaws. These items are included here. We can accept deposits to hold an item for you until the police allow us to release it for sale. Contact Us: For more product information, to order, to find out which store the item is in, to request a transfer to another store, or to confirm stock availability, please call us at 604-263-3221 or toll-free at 1-866-310-3245 or email us: [email protected] Report Date: 06/03/2019 Date: 06/03/2019 Web Used List Time: 08:33 Department Description : DIGITAL CAMERA BATTERIES used Department Name : DCB Product Product Retail Code Name Price 449.QC NIMH