Corporate Archives and the Eastman Kodak Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Ex-Lexes' Cherished Time on Hawaiian Room's Stage POSTED: 01:30 A.M

http://www.staradvertiser.com/businesspremium/20120622__ExLexes_cherished_time_on_Hawaiian_Rooms_stage.html?id=159968985 'Ex-Lexes' cherished time on Hawaiian Room's stage POSTED: 01:30 a.m. HST, Jun 22, 2012 StarAdvertiser.com Last week, we looked at the Hawaiian Room at the Lexington Hotel in New York City, which opened 75 years ago this week in 1937. The room was lush with palm trees, bamboo, tapa, coconuts and even sported a periodic tropical rainstorm, said Greg Traynor, who visited with his family in 1940. The Hawaiian entertainers were the best in the world. The Hawaiian Room was so successful it created a wave of South Seas bars and restaurants that swept the country after World War II. In this column, we'll hear from some of the women who sang and danced there. They call themselves Ex-Lexes. courtesy Mona Joy Lum, Hula Preservation Society / 1957Some of the singers and dancers at the Hawaiian Room in the Lexington Hotel. The women relished the opportunity to "Singing at the Hawaiian Room was the high point of my life," perform on such a marquee stage. said soprano Mona Joy Lum. "I told my mother, if I could sing on a big stage in New York, I would be happy. And I got to do that." Lum said the Hawaiian Room was filled every night. "It could hold about 150 patrons. There were two shows a night and the club was open until 2 a.m. I worked an hour a day and was paid $150 a week (about $1,200 a week today). It was wonderful. -

Kodak-History.Pdf

. • lr _; rj / EASTMAN KODAK COMPANY A Brief History In 1875, the art of photography was about a half a century old. It was still a cumbersome chore practiced primarily by studio professionals and a few ardent amateurs who were challenged by the difficulties of making photographs. About 1877, George Eastman, a young bank clerk in Roch ester, New York, began to plan for a vacation in the Caribbean. A friend suggested that he would do well to take along a photographic outfit and record his travels. The "outfit," Eastman discovered, was really a cartload of equipment that included a lighttight tent, among many other items. Indeed, field pho tography required an individual who was part chemist, part tradesman, and part contortionist, for with "wet" plates there was preparation immediately before exposure, and develop ment immediately thereafter-wherever one might be . Eastman decided that something was very inadequate about this system. Giving up his proposed trip, he began to study photography. At that juncture, a fascinating sequence of events began. They led to the formation of Eastman Kodak Company. George Eastman made A New Idea ... this self-portrait with Before long, Eastman read of a new kind of photographic an experimental film. plate that had appeared in Europe and England. This was the dry plate-a plate that could be prepared and put aside for later use, thereby eliminating the necessity for tents and field processing paraphernalia. The idea appealed to him. Working at night in his mother's kitchen, he began to experiment with the making of dry plates. -

Kodak Movie News; Vol. 3, No. 1; Jan

VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1 JANUARY-FEBRUARY 1955 lntroducing in HERE's a new program on TV Peepers ... a nd Jamie. He also has to his T whichyou willwant to see! Forwethink credit the first Alan Young Show, Operation you will not only delight in "Norb.y" as a Airlift, October Story, and others. Before show, but will also welcome the Iast-minute these TV successes, his unusual talent was news of photo products and developments apparent in Walt Disney's Pinocchio, Peter which the program will bring you-in full Pan, Snow White, and many other films. TV color, if you're equipped to receive it Dave Swift has a deft and sure tauch audi- or in regular black-and-white, as most ences recognize and appreciate. folks will see it. He thinks "Norby" will be the best thing "Norby" is Kodak's first venture jnto he has dorre. So do we. TV. For years we've sought the right ve- "Norby" hicle. Here's why we think you'll like the The story result : The play is named after its leading.character, "Norby" is created, directed, a:nd pro- Pearson Norby, who, in the first show, becomes duced by David Swift. There are two other vice-president in charge of smail loans of the current TV hits, born of his active and per- ceptive mind, you probably know. Mr. Every week on NBC-TV Your family will Iove the NORBY family! Evan Elliot, as Hank Norby, , , Joan Lorring, as Helen Norby . .. Susan Halloran, as Dianne . and David Wayne, as Pearson Norhy First National Bank of Pearl River. -

Eastman Business Park Site Newsletter

Eastman Business Park Site Newsletter Issue 3 Letter from Mike Alt Letter from Arline Liberti Director, Manager, Kodak Fall 2010 Eastman Business Park Rochester Facilities I’ve now been the Director of Eastman Amid all the change and challenge that Business Park (EBP) for five months and surrounds us today in our business world, during this time have had the opportu- the Kodak Rochester Facilities (KRF) mis- nity to meet most of our tenants. sion of creating value in the delivery and Shortly, with the arrival of our three quality of service to our tenants remains Cody Gate Companies, there will be 30 at the core of everything we do. We are tenants at EBP. excited about the new prospects resulting I have spent most of my time networking from Mike’s efforts to attract new tenants externally, focusing on understanding to the site, and are also pleased to share what we need to do to attract new busi- with you a number of improvement initia- nesses and tenants. I’ve attended over tives that will create greater sustainability 10 events, spoke at a NYS Economic De- in support of your business operations on velopment Conference, and hosted at EBP site. more than 20 tours. My learning’s from networking were applied to the develop- 43 Boiler Tube Replacement – On Sep- ment of a strategy for our future busi- tember 12, 2009, the site experienced a ness development. major steam and electric shutdown due to a tube failure on 43 boiler and subsequent Here are the key elements: www.eastmanbusinesspark.com shutdown of other operating boilers. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

Festschrift:Experimenting with Research: Kenneth Mees, Eastman

Science Museum Group Journal Festschrift: experimenting with research: Kenneth Mees, Eastman Kodak and the challenges of diversification Journal ISSN number: 2054-5770 This article was written by Jeffrey Sturchio 04-08-2020 Cite as 10.15180; 201311 Research Festschrift: experimenting with research: Kenneth Mees, Eastman Kodak and the challenges of diversification Published in Spring 2020, Issue 13 Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201311 Abstract Early industrial research laboratories were closely tied to the needs of business, a point that emerges strikingly in the case of Eastman Kodak, where the principles laid down by George Eastman and Kenneth Mees before the First World War continued to govern research until well after the Second World War. But industrial research is also a gamble involving decisions over which projects should be pursued and which should be dropped. Ultimately Kodak evolved a conservative management culture, one that responded sluggishly to new opportunities and failed to adapt rapidly enough to market realities. In a classic case of the ‘innovator’s dilemma’, Kodak continued to bet on its dominance in an increasingly outmoded technology, with disastrous consequences. Component DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201311/001 Keywords Industrial R&D, Eastman Kodak Research Laboratories, Eastman Kodak Company, George Eastman, Charles Edward Kenneth Mees, Carl Duisberg, silver halide photography, digital photography, Xerox, Polaroid, Robert Bud Author's note This paper is based on a study undertaken in 1985 for the R&D Pioneers Conference at the Hagley Museum and Library in Wilmington, Delaware (see footnote 1), which has remained unpublished until now. I thank David Hounshell for the invitation to contribute to the conference and my fellow conferees and colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania for many informative and stimulating conversations about the history of industrial research. -

EXPENDITURE REPORT Page:1 April 1, 2020 to September 30, 2020 SENATOR JOSEPH P

NEW YORK STATE SENATE EXPENDITURE REPORT Page:1 April 1, 2020 to September 30, 2020 SENATOR JOSEPH P. ADDABBO, JR. DEPUTY MAJORITY WHIP OF THE SENATE CHAIR OF RACING, GAMING AND WAGERING COMMITTEE PERSONAL SERVICE EXPENDITURES MEMBER EXPENDITURES Dates Of Service Title Pay Type Amount ADDABBO JR, JOSEPH P 03/19/20 - 09/30/20 MEMBER RA $59,230.78 STAFF EXPENDITURES Employee Dates Of Service Title Pay Type Amount CASSIDY, SHANNA M 03/05/20 - 09/16/20 COMMITTEE DIR & SR. LEGISLATIVE ASST SA $32,307.80 CLARK, VICTORIA L 03/05/20 - 09/16/20 LEGISLATIVE DIRECTOR RA $42,000.00 D'ANGELO, JOHN G 03/05/20 - 09/16/20 CONSTITUENT LIAISON RA $22,615.46 DELLANNO, THOMAS A 03/05/20 - 09/16/20 ASSISTANT COMMUNITY LIAISON SA $5,710.46 DEWEESE, KELLY C 03/05/20 - 09/16/20 DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS RA $35,538.58 DOREMUS, SANDEE 03/05/20 - 09/16/20 COMMUNITY LIAISON RA $22,677.91 GIANNELLI, NEIL C 03/05/20 - 09/16/20 CHIEF OF STAFF RA $35,865.34 GIUDICE, ANTHONY 03/05/20 - 09/16/20 PRESS SECRETARY/SPECIAL EVENTS COORD RA $23,961.56 GRECH, EVA 03/05/20 - 09/16/20 COMMUNITY LIAISON RA $18,389.48 KASH, JANET K 02/21/20 - 08/19/20 COMMUNICATIONS DIRECTOR TE $4,500.00 MOORE, CARL V 03/05/20 - 09/16/20 CONSTITUENT LIAISON RA $24,500.00 PORTH, KRISTI D 03/05/20 - 09/16/20 SCHEDULER RA $23,961.56 SPELLMAN, SARAH E 03/05/20 - 09/16/20 OFFICE MANAGER - MIDDLE VILLAGE RA $25,785.34 GENERAL EXPENDITURES MAINTENANCE & OPERATIONS EXPENDITURES Check Date Voucher# Vendor Description Amount 04/17/20 51071 OFFICE OF GENERAL SERVICES D.O. -

HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Cameras

· V 1965 SPRING SUMMER KODAK PRE·MI MCATALOG HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Cameras ... No. C 11 SMP HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Flasholder For "bounce-back" offers where initial offer was the Hawkeye Instamatic camera. Creates additional sales, gives promotion longer life. Flash holder attaches eas ily to top of Hawkeye Instamatic camera. Makes in door snapshots as easy to take as outdoor ones. No. ASS HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Camera A great self-liquidator. Handsomely styled in teal green and ivory with bright aluminum trim. Hawkeye Instamatic camera laads instantly with No. CS8MP HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Field Case film in handy, drop-in Kodapak cartridges. Takes black-and-white and Perfect choice for "bounce-back" offers where initial color snapshots, and color slides. Extremely easy to use .• • gives en offer was the Hawkeye Instamatic camera or Hawkeye joyment to the entire family. Available in mailer pack. May be person Instamatic F camera. Handsome black simulated alized on special orders with company identification on the camera, either leather case protects camera from dirt and scratches, removable or affixed permanently. facilitates carrying. Supplied flat in mailing envelope. 3 STEPS 1. Dealer load to your customers. TO ORGANIZING Whether your customer operates a supe- market, drug store, service station, or 0 eo" retail business, be sure he is stocked the products your promotion will feo 'eo. AN EFFECTIVE Accomplish this dealer-loading step by fering your customer additional ince .. to stock your product. SELF -LIQUIDATOR For example: With the purchase of • cases of your product, your custo mer ~ ceives a free in-store display and a HA PROMOTION EYE INSTAMATIC F Outfit. -

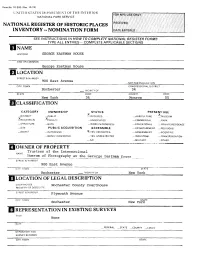

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DhPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC GEORGE EASTMAN HOUSE AND'OR COMMON George Eastman House LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 900 East Avenue _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Rochester . VICINITY OF 34 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New York 36 Monroe 55 ^CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY QWNERSHiP STATUS PRESENT USE X V ^DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM 2ESUILD!NG\S} ^PRIVATE —.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _PARK _-STRUCTURE __BOTH __WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _.OBJECT _IN PROCESS ?-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY __OTHER [OWNER OF PROPERTY Trustees of the International NAME Museum of Photography at the Gerorge EastmQn House STREEF& NUMBER 900 East Avenue STATE Rochester VICINITY OF New York LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. Rochester County Courthouse REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC STREET & NUMBER Plymouth Avenue STATE CITY. TOWN Rochester New York REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None DATE .FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY .__LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD —RUINS ^.ALTERED —MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Eastman residence probably reflects as much of the inventor's desires as it does the architect's design. A local architect, J. Foster Warner, supervised the construction of the house but Eastman chose the design and insisted upon the inclusion of many details which he had observed and photographed in other houses. -

KODAK MILESTONES 1879 - Eastman Invented an Emulsion-Coating Machine Which Enabled Him to Mass- Produce Photographic Dry Plates

KODAK MILESTONES 1879 - Eastman invented an emulsion-coating machine which enabled him to mass- produce photographic dry plates. 1880 - Eastman began commercial production of dry plates in a rented loft of a building in Rochester, N.Y. 1881 - In January, Eastman and Henry A. Strong (a family friend and buggy-whip manufacturer) formed a partnership known as the Eastman Dry Plate Company. ♦ In September, Eastman quit his job as a bank clerk to devote his full time to the business. 1883 - The Eastman Dry Plate Company completed transfer of operations to a four- story building at what is now 343 State Street, Rochester, NY, the company's worldwide headquarters. 1884 - The business was changed from a partnership to a $200,000 corporation with 14 shareowners when the Eastman Dry Plate and Film Company was formed. ♦ EASTMAN Negative Paper was introduced. ♦ Eastman and William H. Walker, an associate, invented a roll holder for negative papers. 1885 - EASTMAN American Film was introduced - the first transparent photographic "film" as we know it today. ♦ The company opened a wholesale office in London, England. 1886 - George Eastman became one of the first American industrialists to employ a full- time research scientist to aid in the commercialization of a flexible, transparent film base. 1888 - The name "Kodak" was born and the KODAK camera was placed on the market, with the slogan, "You press the button - we do the rest." This was the birth of snapshot photography, as millions of amateur picture-takers know it today. 1889 - The first commercial transparent roll film, perfected by Eastman and his research chemist, was put on the market. -

The Rise and Fall of Eastman Kodak: Looking Through Kodachrome Colored Glasses

American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR) 2020 American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research (AJHSSR) e-ISSN : 2378-703X Volume-4, Issue-12, pp-219-224 www.ajhssr.com Research Paper Open Access The Rise and Fall of Eastman Kodak: Looking Through Kodachrome Colored Glasses Peter A. Stanwick1, Sarah D. Stanwick2 1Department of Management/Auburn University, United States 2School of Accountancy/Auburn University, United States Corresponding Author: Peter A. Stanwick ABSTRACT:Eastman Kodak is a truly iconic American brand. Established at the end of the nineteenth century, Kodak revolutionized the photography industry by letting every consumer have the ability to develop their own personal pictures at a low cost. However, Kodak stubbornly continued to embrace film photography long after consumers had shifted to digital based photography. In 2012, Kodak was forced to declare Chapter 11 bankruptcy due to its inability to generate positive cash flows in an industry which had moved beyond film photography. In an attempt to reverse its declining financial performance, Kodak introduced products such as the revised Super 8 camera, a smart phone, cryptocurrency, bitcoin mining and the development of chemicals for generic drugs. All of these new product introductions have failed or have been suspended. In addition, there are questions as to whether the real motive of these “new” product innovations was to be used to aid in the financial recovery of Kodak or were these actions based on manipulating Kodak‟s stock price for the personal gain of its executives. This article concludes by asking the question whether or not it is now time for Kodak to permanently close down its operations. -

Eastman Kodak Annual Report 2020

Eastman Kodak Annual Report 2020 Form 10-K (NYSE:KODK) Published: March 17th, 2020 PDF generated by stocklight.com SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ Annual report pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the year ended December 31, 2019 or ☐ Transition report pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the transition period from _____ to_____ Commission File Number 1-87 EASTMAN KODAK COMPANY (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) NEW JERSEY 16-0417150 (State of incorporation) (IRS Employer Identification No.) 343 STATE STREET, ROCHESTER, NEW YORK 14650 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: 585-724-4000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbols Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, $0.01 par value KODK New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months, and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days.