The Acetate Negative Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013 Call Number Creator Title Date Summary Extent Extent (format) General Notes Related Archival PSC 1 Cerro de la Neblina Cerro de la Neblina Expedition 1984-1989 Field photographs from the 1984-1985 Cerro de la 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 14 slides Includes field notes. Expedition (1984-1985) photographic slides Neblina expedition. Includes one slide from Amazonas, Rio Mavaca Base Camp, March 1989. PSC 2 Abbott, R. E. R. E. Abbott photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature, 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 7 slides Includes field notes. includes Cardinals, red-shouldered hawks, and song sparrow. PSC 3 Byron, Oscar. Abyssinia duplicate slides undated Duplicate slides made from hand-colored lantern 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 100 slides Copy slides from hand colored slides of field photographs in Abyssinia [Ethiopia] lantern slides. circa 1920-1921. PSC 4 Jaques, Francis Lee. ACA textile photographic slides undated ACA Collection. Textiles, 15th to 18th century textiles 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 22 slides from various countries. PSC 5 Bierwert, Thane L. A. A. Allen photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature. 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 154 slides Includes field notes. Collection contains USDE numbers and K numbers. PSC 6 Blanchard, Dean Hobbs. AG Southwest Native Americans undated Field photographs of Southwestern Native 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 3 slides Includes field photographs. photographic slides Americans PSC 7 Amadon, Dean Dean Amadon photographic slides of 1957 Slide of fence post with holes made by Acorn or 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 1 slide Fence post in AMNH Ornithology birds California woodpecker for storage. -

Preparation and Physical Properties of the Biocomposite, Cellulose Diacetate/Kenaf Fiber Sized with Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)

Macromolecular Research, Vol. 18, No. 6, pp 566-570 (2010) www.springer.com/13233 DOI 10.1007/s13233-010-0611-0 Preparation and Physical Properties of the Biocomposite, Cellulose Diacetate/Kenaf Fiber Sized with Poly(vinyl alcohol) Chang-Kyu Lee, Mi Suk Cho, In Hoi Kim, and Youngkwan Lee* Department of Chemical Engineering, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon 440-746, Korea Jae Do Nam Department of Polymer Engineering, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon 440-746, Korea Received November 2, 2009; Revised February 5, 2010; Accepted February 9, 2010 Abstract: Cellulose diacetate (CDA)/kenaf fiber biocomposites were prepared using a melting process. In order to increase the fiber density and compatibilize the kenaf fiber with CDA, the fiber was sized with poly(vinyl alco- hol)(PVA). The sized kenaf fiber was compounded with the plasticized CDA using a twin screw extruder, and the opti- mal processing conditions were determined. The incorporated kenaf fiber improved the mechanical and thermal properties of CDA. In the case of the composites containing 30 wt% kenaf fibers, the tensile strength and modulus increased almost 2 and 3 fold, which were 85.6 MPa and 4831 MPa, respectively. The PVA treated kenaf fiber showed better adhesion to the CDA matrix. Keywords: cellulose diacetate, kenaf fiber, PVA, sizing. Introduction CDA, its processability is improved, whereas its unique mechanical properties and thermal stability are deteriorated. Synthetic polymers are widely used in everyday life and In order to increase the physical strength of CDA, the use of are increasingly being used in more diverse areas due to various reinforcing agents were generally accepted.7-9 Natu- their easy processability, permanent stability, low price, and ral fiber is completely biodegraded in the natural environ- antibacterial properties. -

The Positive and Negative Effects of Photography on Wildlife

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors Program 2020 The Positive and Negative Effects of Photography on Wildlife Joy Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/undergrad-honors Part of the Photography Commons The Positive and Negative Effects of Photography on Wildlife An Honors Thesis Presented to The University Honors Program Gardner-Webb University 10 April 2020 by Joy Smith Accepted by the Honors Faculty _______________________________ ________________________________________ Dr. Robert Carey, Thesis Advisor Dr. Tom Jones, Associate Dean, Univ. Honors _______________________________ _______________________________________ Prof. Frank Newton, Honors Committee Dr. Christopher Nelson, Honors Committee _______________________________ _______________________________________ Dr. Bob Bass, Honors Committee Dr. Shea Stuart, Honors Committee I. Overview of Wildlife Photography The purpose of this thesis is to research the positive and negative effects photography has on animals. This includes how photographers have helped to raise awareness about endangered species, as well as how people have hurt animals by getting them too used to cameras and encroaching on their space to take photos. Photographers themselves have been a tremendous help towards the fight to protect animals. Many of them have made it their life's mission to capture photos of elusive animals who are on the verge of extinction. These people know how to properly interact with an animal; they leave them alone and stay as hidden as possible while photographing them so as to not cause the animals any distress. However, tourists, amateur photographers, and a small number of professional photographers can be extremely harmful to animals. When photographing animals, their habitats can become disturbed, they can become very frightened and put in harm's way, and can even hurt or kill photographers who make them feel threatened. -

Kodak-History.Pdf

. • lr _; rj / EASTMAN KODAK COMPANY A Brief History In 1875, the art of photography was about a half a century old. It was still a cumbersome chore practiced primarily by studio professionals and a few ardent amateurs who were challenged by the difficulties of making photographs. About 1877, George Eastman, a young bank clerk in Roch ester, New York, began to plan for a vacation in the Caribbean. A friend suggested that he would do well to take along a photographic outfit and record his travels. The "outfit," Eastman discovered, was really a cartload of equipment that included a lighttight tent, among many other items. Indeed, field pho tography required an individual who was part chemist, part tradesman, and part contortionist, for with "wet" plates there was preparation immediately before exposure, and develop ment immediately thereafter-wherever one might be . Eastman decided that something was very inadequate about this system. Giving up his proposed trip, he began to study photography. At that juncture, a fascinating sequence of events began. They led to the formation of Eastman Kodak Company. George Eastman made A New Idea ... this self-portrait with Before long, Eastman read of a new kind of photographic an experimental film. plate that had appeared in Europe and England. This was the dry plate-a plate that could be prepared and put aside for later use, thereby eliminating the necessity for tents and field processing paraphernalia. The idea appealed to him. Working at night in his mother's kitchen, he began to experiment with the making of dry plates. -

Bronica Sq-A-M.Pdf

Congratulations on your choice of the Zenza Bronica SQ-Am single lens reflex camera which has been developed to provide the user with high quality performance, simple handling convenience and extremely useful versatility plus automatic motorized film winding and shutter cocking operations suitable for the professional photographer. Although the Zenza Bronica SQ-Am has been designed exclusively for motorized operations, it has, also, been developed as a complete modular "system" camera possessing complete interchangeability with the interchangeable lenses and accessories developed for the SQ and SQ-A models, on which the SQ-Am is also based, and, therefore, provides the user with a very high degree of motorization in daily operations, in addition to automatic film winding and shutter cocking actions. Although instructions following are based on a standard combination consisting of the SQ-Am main body with Zenzanon-S 80mm lens, Film Back SQ 120 and WaistLevel Finder S, the choice of the lens, film back and finder is left to the discretion of the photographer, who should choose those items best suited to the type of assignments contemplated. To obtain best results from the Zenza Bronica SQ-Am, may we suggest that you read this instruction manual through carefully, before you even touch the camera, as your pleasure in using the camera will be even greater if you thoroughly familiarize yourself with its working parts before loading your first roll of film. CONTENTS Specifications of the ZENZA 17. Interchanging Finders ................................23 BRONICA SQ-Am ......................................... 2 18. Waist-Level Finder and Parts of the ZENZA BRONICA Interchanging Magnifiers ..................................23 19. -

Cyanotype Detailed Instructions

Cyanotype Detailed Instructions Cyanotype Formula, Mixing and Exposing Instructions 1. Dissolve 40 g (approximately 2 tablespoons) Potassium Ferricyanide in 400 ml (1.7 cups) water to create STOCK SOLUTION A. Allow 24 hours for the powder to fully dissolve. 2. Dissolve 100 g (approximately .5 cup) Ferric Ammonium Citrate in 400 ml (1.7 cups) water to create if you have Chemistry Open Stock START HERE STOCK SOLUTION B. Allow 24 hours for the powder to fully dissolve. If using the Cyanotype Sensitizer Set, simply fill each bottle with water, shake and allow 24 hours for the powders to dissolve. 3. In subdued lighting, mix equal parts SOLUTION A and SOLUTION B to create the cyanotype sensitizer. Mix only the amount you immediately need, as the sensitizer is stable just 2-4 hours. if you have the Sensitizer Set START HERE 4. Coat paper or fabric with the sensitizer and allow to air dry in the dark. Paper may be double-coated for denser prints. Fabric may be coated or dipped in the sensitizer. Jacquard’s Cyanotype Fabric Sheets and Mural Fabrics are pre-treated with the sensitizer (as above) and come ready to expose. 5. Make exposures in sunlight (1-30 minutes, depending on conditions) or under a UV light source, placing ob- jects or a film negative on the coated surface to create an image. (Note: Over-exposure is almost always preferred to under-exposure.) The fabric will look bronze in color once fully exposed. 6. Process prints in a tray or bucket of cool water. Wash for at least 5 minutes, changing the water periodically, if you have until the water runs clear. -

FILM FORMATS ------8 Mm Film Is a Motion Picture Film Format in Which the Filmstrip Is Eight Millimeters Wide

FILM FORMATS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 8 mm film is a motion picture film format in which the filmstrip is eight millimeters wide. It exists in two main versions: regular or standard 8 mm and Super 8. There are also two other varieties of Super 8 which require different cameras but which produce a final film with the same dimensions. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Standard 8 The standard 8 mm film format was developed by the Eastman Kodak company during the Great Depression and released on the market in 1932 to create a home movie format less expensive than 16 mm. The film spools actually contain a 16 mm film with twice as many perforations along each edge than normal 16 mm film, which is only exposed along half of its width. When the film reaches its end in the takeup spool, the camera is opened and the spools in the camera are flipped and swapped (the design of the spool hole ensures that this happens properly) and the same film is exposed along the side of the film left unexposed on the first loading. During processing, the film is split down the middle, resulting in two lengths of 8 mm film, each with a single row of perforations along one edge, so fitting four times as many frames in the same amount of 16 mm film. Because the spool was reversed after filming on one side to allow filming on the other side the format was sometime called Double 8. The framesize of 8 mm is 4,8 x 3,5 mm and 1 m film contains 264 pictures. -

Cellulose Acetate Microfilm Forum

Addressing Cellulose Acetate Microfilm from a British Library Perspective The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Shenton, Helen. 2005. Addressing cellulose acetate microfilm from a British library perspective. Liber Quarterly 15(2). Published Version http://liber.library.uu.nl/publish/articles/000134/article.pdf Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3965108 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Addressing Cellulose Acetate Microfilm from a British Library perspective by HELEN SHENTON INTRODUCTION This paper is about cellulose acetate microfilm from the British Library perspective. It traces how acetate microfilm became an issue for the British Library and describes cellulose acetate deterioration. This is followed by details of what has already been done about the situation and what action is planned for the future. THE PROBLEM: CELLULOSE ACETATE DETERIORATION In order to tackle the issue it was important to be clear about what cellulose acetate deterioration is, and what can be done about it. Cellulose acetate replaced cellulose nitrate in the late 1940s and was called safety film. This was in use until the mid-1980s, when it was replaced by polyester. One definition of cellulose acetate film from the Image Permanence Institute’s Storage Guide for Acetate Film has not been bettered: “Cellulose acetate film is a modified form of cellulose, and can slowly decompose under the influence of heat, moisture and acids. -

Photographic Films

PHOTOGRAPHIC FILMS A camera has been called a “magic box.” Why? Because the box captures an image that can be made permanent. Photographic films capture the image formed by light reflecting from the surface being photographed. This instruction sheet describes the nature of photographic films, especially those used in the graphic communications industries. THE STRUCTURE OF FILM Protective Coating Emulsion Base Anti-Halation Backing Photographic films are composed of several layers. These layers include the base, the emulsion, the anti-halation backing and the protective coating. THE BASE The base, the thickest of the layers, supports the other layers. Originally, the base was made of glass. However, today the base can be made from any number of materials ranging from paper to aluminum. Photographers primarily use films with either a plastic (polyester) or paper base. Plastic-based films are commonly called “films” while paper-based films are called “photographic papers.” Polyester is a particularly suitable base for film because it is dimensionally stable. Dimensionally stable materials do not appreciably change size when the temperature or moisture- level of the film change. Films are subjected to heated liquids during processing (developing) and to heat during use in graphic processes. Therefore, dimensional stability is very important for graphic communications photographers because their final images must always match the given size. Conversely, paper is not dimen- sionally stable and is only appropriate as a film base when the “photographic print” is the final product (as contrasted to an intermediate step in a multi-step process). THE EMULSION The emulsion is the true “heart” of film. -

Basic View Camera

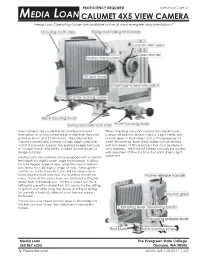

PROFICIENCY REQUIRED Operating Guide for MEDIA LOAN CALUMET 4X5 VIEW CAMERA Media Loan Operating Guides are available online at www.evergreen.edu/medialoan/ View cameras are usually tripod mounted and lend When checking out a 4x5 camera from Media Loan, themselves to a more contemplative style than the more patrons will need to obtain a tripod, a light meter, one portable 35mm and 2 1/4 formats. The Calumet 4x5 or both types of film holders, and a changing bag for Standard model view camera is a lightweight, portable sheet film loading. Each sheet holder can be loaded tool that produces superior, fine grained images because with two sheets of film, a process that must be done in of its large format and ability to adjust for a minimum of total darkness. The Polaroid holders can only be loaded image distortion. with one sheet of film at a time, but each sheet is light Media Loan's 4x5 cameras come equipped with a 150mm protected. lens which is a slightly wider angle than normal. It allows for a 44 degree angle of view, while the normal 165mm lens allows for a 40 degree angle of view. Although the controls on each of Media Loan's 4x5 lens may vary in terms of placement and style, the functions remain the same. Some of the lenses have an additional setting for strobe flash or flashbulb use. On these lenses, use the X setting for use with a strobe flash (It’s crucial for the setting to remain on X while using the studio) and the M setting for use with a flashbulb (Media Loan does not support flashbulbs). -

General Introduction Sustainability Issues in the Preservation of Black and White Cellulose Esters Film- Based Negatives Collections

Élia Catarina Tavares Costa Roldão Licenciada em Conservação e Restauro A contribution for the preservation of cellulose esters black and white negatives Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Ciências da Conservação do Património, Especialidade em Ciências da Conservação Orientador: Doutora Ana Maria Martelo Ramos, Professora Associada, FCT NOVA Co-orientadores: Doutor Bertrand Lavédrine, CRC Doutor António Jorge D. Parola, Professor Associado com Agregação, FCT NOVA Júri: Presidente: Doutora Maria João Seixas de Melo, Professora Catedrática, FCTNOVA Arguentes: Doutor Hugh Douglas Burrows, Professor Catedrático Jubilado, FCT-UC Doutora Ana Isabel S. C. Delgado Martins, Directora do AHU-DGLAB Vogais: Doutora Ana Maria Martelo Ramos, Professora Associada, FCT NOVA Doutor João Pedro Martins de Almeida Lopes, Professor Auxiliar, FF- UL Novembro, 2018 A contribution for the preservation of cellulose esters black and white negatives Copyright © Élia Catarina Tavares Costa Roldão, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Universidade Nova de Lisboa. A Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia e Universidade Nova de Lisboa têm o direito, perpétuo e sem limites geográficos, de arquivar e publicar esta dissertação através de exemplares impressos reproduzidos em papel ou de forma digital, ou por qualquer outro meio conhecido ou que venha a ser inventado, e de divulgar através de repositórios científicos e de admitir a sua cópia e distribuição com objectivos educacionais ou de investigação, não comerciais, desde que seja dado crédito ao autor e editor. -

HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Cameras

· V 1965 SPRING SUMMER KODAK PRE·MI MCATALOG HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Cameras ... No. C 11 SMP HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Flasholder For "bounce-back" offers where initial offer was the Hawkeye Instamatic camera. Creates additional sales, gives promotion longer life. Flash holder attaches eas ily to top of Hawkeye Instamatic camera. Makes in door snapshots as easy to take as outdoor ones. No. ASS HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Camera A great self-liquidator. Handsomely styled in teal green and ivory with bright aluminum trim. Hawkeye Instamatic camera laads instantly with No. CS8MP HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Field Case film in handy, drop-in Kodapak cartridges. Takes black-and-white and Perfect choice for "bounce-back" offers where initial color snapshots, and color slides. Extremely easy to use .• • gives en offer was the Hawkeye Instamatic camera or Hawkeye joyment to the entire family. Available in mailer pack. May be person Instamatic F camera. Handsome black simulated alized on special orders with company identification on the camera, either leather case protects camera from dirt and scratches, removable or affixed permanently. facilitates carrying. Supplied flat in mailing envelope. 3 STEPS 1. Dealer load to your customers. TO ORGANIZING Whether your customer operates a supe- market, drug store, service station, or 0 eo" retail business, be sure he is stocked the products your promotion will feo 'eo. AN EFFECTIVE Accomplish this dealer-loading step by fering your customer additional ince .. to stock your product. SELF -LIQUIDATOR For example: With the purchase of • cases of your product, your custo mer ~ ceives a free in-store display and a HA PROMOTION EYE INSTAMATIC F Outfit.