The Governance of Public Special Schools in the Western Cape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Schools

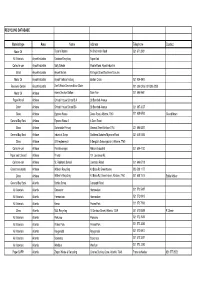

Province District Name PrimaryDisability Postadd1 PhysAdd1 Telephone Numbers Fax Numbers Cell E_Mail No. of Learners No. of Educators Western Cape Metro South Education District Agape School For The CP CP & Physical disability P.O. Box23, Mitchells Plain, 7785 Cnr Sentinel and Yellowwood Tafelsig, Mitchells Plain 213924162 213925496 [email protected] 213 23 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Alpha School Autism Spectrum Dis order P.O Box 48, Woodstock, 7925 84 Palmerston Road Woodstock 214471213 214480405 [email protected] 64 12 Western Cape Metro East Education District Alta Du Toit School Intellectual disability Private Bag x10, Kuilsriver, 7579 Piet Fransman Street, Kuilsriver 7580 219034178 219036021 [email protected] 361 30 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Astra School For Physi Physical disability P O Box 21106, Durrheim, 7490 Palotti Road, Montana 7490 219340155 219340183 0835992523 [email protected] 321 35 Western Cape Metro North Education District # Athlone School For The Blind Visual Impairment Private BAG x1, Kasselsvlei Athlone Street Beroma, Bellville South 7533 219512234 219515118 0822953415 [email protected] 363 38 Western Cape Metro North Education District Atlantis School Of Skills MMH Private Bag X1, Dassenberg, Atlantis, 7350 Gouda Street Westfleur, Atlantis 7349 0215725022/3/4 215721538 [email protected] 227 15 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Batavia Special School MMH P.O Box 36357, Glosderry, 7702 Laurier Road Claremont 216715110 216834226 -

13-17 July 2015 Name of School Surname Name Total

13-17 July 2015 Name of School Surname Name Total HS Porterville Breytenbach Elmarie Steynville Sek Carstens Liza-Mari Vooruitsig PS De Bruyn Johan HS Dirkie Uys De Vreye Leney HS Swartland Du Preez I Vooruitsig PS Engelbrecht Richard Stawelklip PS Faro Mathilda Willemsvallei PS Fortuin PM HS Swartland Gerber R HS Aurora Horne Susarah Schoon-spruit Sek Karstens Tashline Riebeek-Wes PS Mentoor Maurese Riebeek-Wes PS Mentoor Nicola Riebeek-Wes PS Nel Karen Schoon-spruit Sek Rinquest Jade Stawelklip PS Schaffers Brandon Wesbank Sek Strydom Steel Laurie Hugo PS Swart John Laurie Hugo PS Swart John Gary Wesbank Sek Van der Merwe Eunice Schoon-spruit Sek Van der Merwe Anneke Schoon-spruit Sek Van der Merwe Brynmor Steynville Sek Van Rooyen Rashonia HS Swartland Visser GJ Wesbank Sek Willemse Sharon Ashton PC (CW) Gqamana Luvuyo Ashton PC (CW) Magida Noxolo Van Cutsem (CW) Zondo Siphumuzile Van Cutsem (CW) Tose Vuyani, Masakheke HS (CW) Harmse Shaun Masakheke HS (CW) Basvi Stevin Paul Roos Gim Canaris Christine Vusisiswe Secondary Kula Phumla Vusisiswe Secondary Mthenjana Patrick Iingcinga Zethu Yame Mninawe Makapula Noji Nolubabalo Makupula Den Merg Diza Makupula Magwaca Nomfuneko Desmond Tutu Nqoyo Nompume-lelo Desmond Tutu Mbulawa Bukelwa Desmond Tutu Siduma Mandla Kayamandi HS Ngcwebo Ntombi Kayamandi HS Mpokeli Zanomzi Kayamandi HS Phinda Makapela Langeberg Williams Esther Langeberg Eksteen Henry Langeberg Munnik Melvyn De Kruine Sek April Yolandi Ilingellethu HS Mhambi Unathi Ilingellethu HS Mangcengeza Wandile Diazville HS Kaba Nomveliso -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

The Youth Book. a Directory of South African Youth Organisations, Service Providers and Resource Material

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 432 485 SO 029 682 AUTHOR Barnard, David, Ed. TITLE The Youth Book. A Directory of South African Youth Organisations, Service Providers and Resource Material. INSTITUTION Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria (South Africa). ISBN ISBN-0-7969-1824-4 PUB DATE 1997-04-00 NOTE 455p. AVAILABLE FROM Programme for Development Research, Human Sciences Research Council, P 0 Box 32410, 2017 Braamfontein, South Africa; Tel: 011-482-6150; Fax: 011-482-4739. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC19 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Developing Nations; Educational Resources; Foreign Countries; Schools; Service Learning; *Youth; *Youth Agencies; *Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS Service Providers; *South Africa; Youth Service ABSTRACT With the goal of enhancing cooperation and interaction among youth, youth organizations, and other service providers to the youth sector, this directory aims to give youth, as well as people and organizations involved and interested in youth-related issues, a comprehensive source of information on South African youth organizations and related relevant issues. The directory is divided into three main parts. The first part, which is the background, is introductory comments by President Nelson Mandela and other officials. The second part consists of three directory sections, namely South African youth and children's organizations, South African educational institutions, including technical training colleges, technikons and universities, and South African and international youth organizations. The section on South African youth and children's organizations, the largest section, consists of 44 sectoral chapters, with each organization listed in a sectoral chapter representing its primary activity focus. Each organization is at the same time also cross-referenced with other relevant sectoral chapters, indicated by keywords at the bottom of an entry. -

Material Type Area Name Address Telephone Contact RECYCLING DATABASE

RECYCLING DATABASE Material type Area Name Address Telephone Contact Motor Oil - Taylor's Motors 14 Chichester Road 021 671 2931 All Materials Airport Industria Rainbow Recycling Airport Ind Collect-a-can Airport Industria Solly Sebola Mobile Road, Airpot industria Metal Airport Industria Airport Metals Michigan Street/'Northern Suburbs Motor Oil Airport Industria Airport Vehicle Testing Boston Circle 021 934 4900 Recovery Centre Airport Industria Don't Waste Services Brian Slater 021 386 0206 / 021 386 0208 Motor Oil Athlone Adens Service Station Eden Ave 021 696 9941 Paper-Mondi Athlone Christel House School S A 38 Bamford Avenue Other Athlone Christel House School SA 38 Bamford Avenue 021 697 3037 Glass Athlone Express Waste Desre Road, Athlone, 7760 021 638 6593 Gerard Moen General Buy Back Athlone Express Waste 2 5 Desri Road Glass Athlone Garlandale Primary General Street Athlone 7764 021 696 8327 General Buy Back Athlone Industrial Scrap Southern Suburbs/'Mymona Road 021 448 5395 Glass Athlone LR Heydenreych 5 Bergzich Schoongezicht, Athlone, 7760 Collect-a-can Athlone Pen Beverages Athlone Industrial 021 684 4130 Paper and C/board Athlone Private 151 Lawrence Rd, Collect-a-can Athlone St. Raphaels School Lawrence Road 021 696 6718 Glass/ tins/ plastic Athlone Walkers Recycling 43 Brian Rd Greenhaven 083 508 1177 Glass Athlone Walker's Recycling 43 Brian Rd, Greenhaven, Athlone, 7760 021 638 1515 Eddie Walker General Buy Back Atlantis Berties Scrap Conaught Road All Materials Atlantis Grosvenor Hermeslaan 021 572 5487 All Materials -

A Post COVID-19 World, and Learning to Managing Editor Faiza Steyn Contents Adapt to the Changes It Will Bring

BETTER ISSUETOGETHER. | June 2020 37 A post COVID-19 COVID-19 world service excellence ADAPTING Our frontline and backline heroes TODAY AND INTO One app for the WCG THE FUTURE Service delivery at a click Beating coronavirus A story of hope and recovery editor’s note Preparing for MAGAZINE TEAM a post COVID-19 world, and learning to Managing Editor Faiza Steyn contents adapt to the changes it will bring. Editor adapting to change Leah Moodaley Proofreaders ISSUE 37 JUNE 2020 in uncertainty Aré van Schalkwyk, Mishqa Rossier Afrikaans translation How has COVID-19 impacted our Aré van Schalkwyk corporate wellness? page 6 Since the distribution of our last magazine in March, our provincial isiXhosa translation administration, and society at large, has had to adapt to operating Luvuyo Martins in an unusual way. Under lockdown, the magazine team had to Contributors adjust to a situation where our face-to-face interviews and hands-on Byron La Hoe, CapeNature, photoshoots were an unnecessary risk in the face of a spreading Fatima Gallie, Florence Kotze, virus. We had to produce a magazine that stands for all things Haybre Philander, Hayley Baron, Jako Smith, Khuthala Swanepoel, “Better Together”, separate from one another. Landeka Diamond, Larissa Venter, We had to adapt to sudden change, which is why this issue is unique. Laticia Pienaar, Maret Lesch, Our current circumstances have forced all of us to see and do things Mishqa Rossier, Natalie Roman, Nomakhaya Mngqibisa, differently in the face of much uncertainty. Robert Shaw, Trevor Luthango, What have the past three months made you realise? As you reflect Wendy Horn from the perspective of a mother, father, daughter, son, sister, or Layout and design brother – and as a Western Cape Government employee – think about Corporate Communication what you are learning from this experience and how you can use these Art Director lessons to empower yourself moving forward. -

Social Cluster

PROGRAME PORTFOLIO COMMITTEE ON BASIC EDUCATION Parliament of South Africa DRAFT PROGRAMME: 31 July – 4 August 2017 OVERSIGHT AND MONITORING VISIT: STATE OF SCHOOLING 2017 EDUCATION DISTRICTS WESTERN CAPE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT THE PORTFOLIO COMMIT TEE ON BASIC EDUCATI ON Day 1: Monday, 31 July 2017 06:30 – 08:00 Delegation shuttled from Parliamentary Villages to the Western Cape Education Department Offices (Boardroom 4, 2nd Floor, Grand Central Building) 08:00 – 11:00 Meeting: National Department of Basic Education, WCED (including the Office of the MEC, HOD, Senior and District Officials), Portfolio Committee on Education (Provincial Legislature), SGB Associations, Organised Labour, SA Principals Association) (Boardroom 4, 2nd Floor, Grand Central Building) 11:30 – 18:00 Visit to Schools: 11:30 – 13:00 Langa Secondary School (Langa) (15min/12km) 13:30 – 15:00 Thembani Primary (Langa) (5 min/450m) 15:30 – 17:00 Manenberg Secondary School (Manenberg) (13min/9.5km) Or Mount View Sec (Hanover Park) (12min/9.9km) 17:30 – 19:00 Nompumelelo School (Gugulethu) (11min/7km) Day 2: Tuesday, 1 August 2017 06:30 – 08:00 Delegation shuttled from Parliamentary Villages to Siviwe School of Skills (Gugulethu) 08:30 – 10:00 Visits to School: Siviwe School of Skills (Gugulethu) 10:30 – 18:00 DELEGATION SPLIT INTO TWO (2) TEAMS Team A: Hon N Gina, Hon T M Z Khoza, Hon I Ollis, Hon C N Majeke, Mr D Bandi, Mr M Kekana, Ms R Azzakani (2 x 7-seater vans) Team B: Hon N Mokoto, Hon H D Khosa, Hon N Tarabella-Marchesi, Hon X Ngwezi, Mr L Brown, Mr M Erasmus (1 -

Western Cape Government Provincial Treasury

Western Cape Government Provincial Treasury BUDGET 2018 SPEECH Minister of Finance Dr IH Meyer 6 March 2018 Budget Speech 2018 Western Cape Government Honourable Speaker and Deputy Speaker Honourable Premier and Cabinet Colleagues Honourable Leader of the Official Opposition Honourable Leaders of Opposition Parties Honourable Members of the Western Cape Legislature Executive Mayors and Executive Deputy Mayors Speakers and Councillors Senior officials of the Western Cape Government Leaders of the Business Community Citizens of the Western Cape Ladies and Gentlemen Madam Speaker, the 2018 Budget focuses on budgeting for the people, recognising that economic growth and development is critical to improve living standards and socio-economic conditions and therefore the pursuit thereof remains a top priority of this Government. Speaker, sedert die Minister van Finansies sy hoofbegroting in die Parlement ter tafel gelê het op 23 Februarie 2018, het ons nou weer ‘n nuwe Minister by die Nasionale Tesourie. Ek verwelkom die terugkeer van Minister Nene by die Nasionale Tesourie. Minister Nene sal eers die Nasionale Tesourie moet skoonmaak want die agente van staatskaping is deur sy voorganger, Minister Gigaba, in die Nasionale Tesourie ontplooi. Ongelukkig het die Gupta dogmas aspekte van die Nasionale Begroting vertroebel en herbesinning is noodsaaklik as ons uit ‘n begrotingsperspektief ‘n nuwe begin wil maak. Dit sluit in die bestuur van die 2 Budget Speech 2018 Western Cape Government uitgawe kant van die Begroting en of die verhoging in BTW werklik noodsaaklik was gegewe die fiskale konteks. It is my intention to write to Minister Nene to request him to restore the credibility and integrity of the National Treasury as the supreme fiscal authority in South Africa. -

Western Cape No Fee Schools 2015

WESTERN CAPE NO FEE SCHOOLS 2015 NATIONAL NAME OF SCHOOL SCHOOL PHASE ADDRESS OF SCHOOL EDUCATION DISTRICT QUINTILE LEARNER EMIS 2015 NUMBERS NUMBER 2015 0127337447 A.F. KRIEL VGK PRIM. Primary School Posbus 483,Montagu,6720 CAPE WINELANDS 1 52 0130338087 AAN DE DOORNS NGK PRIM. Primary School Posbus 934,Worcester,6850 CAPE WINELANDS 1 157 0140330329 ACACIA PRIM. Primary School Posbus 85,Laingsburg,6900 EDEN AND CENTRAL KAROO 1 826 0126336831 AGTERWITZENBERG VGK PRIM. Primary School Posbus 166,Ceres,6835 CAPE WINELANDS 1 94 0117337862 AKKERBOOM PRIM. Primary School Posbus 118,Barrydale,6750 OVERBERG 1 33 0108470023 ALFONS PRIM. Primary School Posbus 2080,WINDMEUL,7630 CAPE WINELANDS 1 205 0130041109 ALFRED STAMPER PUB. PRIM. Primary School P O Box 109,Worcester,6849 CAPE WINELANDS 1 850 0123358290 ALGERYNSKRAAL LB PRIM. Primary School Posbus 433,LADISMITH,6655 EDEN AND CENTRAL KAROO 1 32 0123358282 AMALIENSTEIN LB PRIM. Primary School Posbus 110,Ladismith,6655 EDEN AND CENTRAL KAROO 1 313 P.O. Box 225,Malmesbury,PAARDEBERG 0132476021 ANNE PIENAAR GEDENK NGK PRIM. Primary School WEST COAST 1 232 DISTRICT,7300 0114336394 ARIESKRAAL SSKV PRIM. Primary School Posbus 81,Grabouw,7160 OVERBERG 1 165 0125357758 AVONTUUR LB PRIM. Primary School Posbus 9,Avontuur,6490 EDEN AND CENTRAL KAROO 1 164 0140337331 BAARTMANSFONTEIN NGK PRIM. Primary School Posbus 185,Laingsburg,6900 EDEN AND CENTRAL KAROO 1 39 0127337404 BADEN NGK PRIM. Primary School Posbus 303,Montagu,6720 CAPE WINELANDS 1 50 0114336599 BEREA MOR PRIM. Primary School Kerkstraat,Bereaville,7232 OVERBERG 1 311 0108476730 BERGENDAL SSKV PRIM. Intermediate School Posbus 514,Suider-Paarl,7624 CAPE WINELANDS 1 370 0133476064 BERGHOF NGK PRIM. -

Arc Port.Indd

Nawal Mohamad Architecture Portfolio 2014-2019 Human life is a combination of tragedy and comedy. The shapes and designs that surround us are the music accompanying this tragedy and this comedy. - Alvar Aalto Contents Resume 4 2017 Final BAS Design Project Artisan Center 5 Merchant’s House 11 2016 Bo Kaap House 16 2017 Envisaged City 22 2014-2019 Work Experience 25 Helen Gardner Travel Prize 27 Film Photography 28 | 3 NAWAL MOHAMAD University of Cape Town, BAS (Hons) EDUCATION EXPERIENCE MOST PROUD OF +27715797697 [email protected] Bachelor of Architectural Studies (BAS) Architecture Intern Helen Gardner Travel Prize Cape Town, South Africa University of Cape Town Stauch Vorster Architects nawalmohamad.wordpress.com 2015-2017 South Africa 2018 Cape Town, South Africa Selected from 20 applicants who completed the BAS program for best writing and research proposal in ar- • Key Courses: • Worked in a team with a focus on residential projects, chitecture. The award is given to the applicant who is Design and Theory Studio, Technology, History and scaling from social housing to upmarket apartments. most likely to bene t from overseas travel. My research Theory of Architecture, Theory of Structures, Manage- • Designed brochures for clients, designed proposals was conducted in India. (2018) ment and Practice Law, Representation for new sites, digitally modeled buildings and pre- pared local council drawings. Dell Young Leader • Managed site visits that required scanning for con- Level 5 TEFL Certi cate struction errors and logging it on the network cloud. Selected in the top 50 rst year students at UCT for The TEFL Academy, UK this scholarship after displaying leadership potential 2018 Online and the ability to overcome adversity. -

Jrýk, Msolkw Olm. Oo R. Mix~ P 4 La Going W, 11 Ill M Ii

wo wo 21 ~ ;k!, . .... .... Yt W:j . 2: mamew~ ,jrýk, msolkw Olm. oo r. mix~ p 4 la going W, 11 ill M Ii. immel hell .1m"dmgdmgdmdwmawaw . ... ... ...... ..... im ljniffi alibi: Nwalm, Offi . ..... Offi Offi 1160.1 00 i Wi 001.1 Ni .......... iw ........... .... ~New~ .1mall 0 111 all . ........ ....... AP AÅL- A SURVEY OF RACE RELATIONS IN SOUTH AFRICA 1964 Compiled by MURIEL HORRELL Research Officer South African Institute of Race Relations SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF RACE RELATIONS P.O. Box 97 JOHANNESBURG 1965 ACKNOWLEDGEM ENTS Again Dr. Ellen Hellmann checked the manuscript of this Survey, made invaluable suggestions for its improvement, contributed material to fill various gaps, and gave constant encouragement. Dr. Hellmann's help was appreciated more than ever this year because the writer had been overseas for five months and out of close touch with the South African scene. During this period Miss Mary Draper of the Institute's staff spent a great deal of time collecting material for the Survey, analysing legislation, and summarizing official documents. She was assisted by Miss Lesley Cawood and Miss Brenda Adams. Very sincere appreciation is expressed to them for their contributions. Mr. Quintin Whyte and Mr. F. J. van Wyk kindly checked certain sections of the manuscript. Mr. Stanley Osler generously allowed the writer to make use of educational material he had obtained. Numerous Government and Provincial Departments furnished information. The writer is indebted, too, to Mrs. Merle Stoltenkamp and Mrs. M. Dickson, who did the typing; to Mr. L. Hotz and Mrs. A. Honeywill, who saw the manuscript through the Press; to the staff of the Institute's library; and to the printers, The Natal Witness (Pty.) Ltd. -

44028 24-12 Roadcarrierp

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID AFRIKA Regulation Gazette No. 10177 Regulasiekoerant December Vol. 666 24 2020 No. 44028 Desember ISSN 1682-5843 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 44028 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure . 2 No. 44028 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 24 DECEMBER 2020 No. 44028 2 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. Contents Page No. Transport, Department of Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Applications for Permits Menlyn ..........................................................................................................................................................................3 Applications concerning Operating Licences Goodwood ....................................................................................................................................................................8 This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 3 No. 44028 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 24 DECEMBER 2020 No. 44028 3 . Transport, Department of Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Applications for Permits Menlyn CROSS-BORDER ROAD TRANSPORT AGENCY APPLICATIONS FOR PERMITS Particulars in respect of applications for permits as submitted