Smart Living Handbook Full Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

XCHANGE SOUTH AFRICA . . . More Than Just the Best Internships

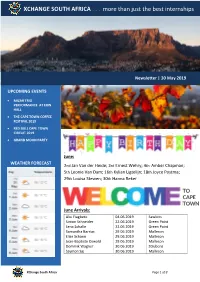

XCHANGE SOUTH AFRICA . more than just the best internships Newsletter | 30 May 2019 NEWSLETTER | 01 January 2018 UPCOMING EVENTS MIZAR TRIO PERFORMANCE AT ERIN HALL THE CAPE TOWN COFFEE FESTIVAL 2019 RED BULL CAPE TOWN CIRCUIT 2019 GRAND MOON PARTY June: WEATHER FORECAST 2nd Jan Van der Heide; 3rd Ernest Wehry; 4th Amber Chapman; 5th Leonie Van Dam; 16th Kylian Ligtelijn; 18th Joyce Postma; 29th Louisa Stewen; 30th Hanna Reker TO CAPE TOWN June Arrivals: Aku Fiagbeto 04.06.2019 Sawkins Simon Schneider 22.06.2019 Green Point Lena Schalle 22.06.2019 Green Point Samantha Barriac 29.06.2019 Malleson Elise Schann 29.06.2019 Malleson Jean-Baptiste Oswald 29.06.2019 Malleson Dominik Wagner 30.06.2019 Strubens Szymon Saj 30.06.2019 Malleson XChange South Africa Page 1 of 8 More Wonderful Ways To Experience Cape Town WATCH A SHOW @ ARTSCAPE Between Table Mountain and Table Bay, the City of Cape Town boasts a cosmopolitan mix of historic and modern landmarks. One of these is the Artscape Theatre Centre on the Foreshore, home to the Artscape performing arts company. With its close proximity to Cape Town’s central business district, the new International Convention Centre and the V & A Waterfront, Artscape is ideally situated to serve the Cape’s performing arts, film, tourism, entertainment, conference, and exhibition industries. Open every day from 08h00 – 17h00, Cost: dependent on show. Artscape/ D.F. Malan St / Foreshore Cape Town / http://www.artscape.co.za/whats-on- now/ TANDEM SKYDIVING WITH MOTHERCITY SKYDIVING A Tandem Introductory skydive is unquestionably the quickest, easiest and safest way to experience skydiving for the first time. -

Measuring the Effects of Political Reservations Thinking About Measurement and Outcomes

J-PAL Executive Education Course in Evaluating Social Programmes Course Material University of Cape Town 23 – 27 January 2012 J-PAL Executive Education Course in Evaluating Social Programmes Table of Contents Programme ................................................................................................................................ 3 Maps and Directions .................................................................................................................. 5 Course Objectives....................................................................................................................... 7 J-PAL Lecturers ......................................................................................................................... 9 List of Participants .................................................................................................................... 11 Group Assignment .................................................................................................................. 12 Case Studies ............................................................................................................................. 13 Case Study 2: Learn to Read Evaluations ............................................................................... 18 Case Study 3: Extra Teacher Program .................................................................................... 27 Case Study 4: Deworming in Kenya ....................................................................................... 31 Exercises -

Sunsquare City Bowl Fact Sheet 8.Indd

Opens September 2017 Lobby Group and conference fact sheet Standard room A city hotel for the new generation With so much to do and see in Cape Town, you need to stay somewhere central. Situated on the corner of Buitengracht and Strand Street, the bustling location of SunSquare Cape Town City Bowl inspires visitors to explore the hip surroundings and get to know the city. The bedrooms The hotel’s 202 rooms are divided into spacious standard rooms with queen The Deck Bar size beds, twin rooms each with 2 double beds, 5 executive rooms, 2 suites and 2 wheelchair accessible rooms. Local attractions Hotel services Long Street - 200 m • Rooftop pool with panoramic views of the V&A Waterfront and Signal Hill CTICC - 1 km • Fitness centre on the top fl oor with views of Table Mountain Artscape Theatre - 1 km • 500 MB free high-speed WiFi per room, per day V&A Waterfront - 2 km • Rewards cardholders get 2GB free WiFi per room, per day Cape Town Stadium - 2 km Two Oceans Aquarium - 2 km Table Mountain Cable Way - 5 km Other facilities • Vigour & Verve restaurant • Transfer services • Rooftop Deck Bar and Lounge • Shuttle service (on request) Contact us • Secure basement parking • Car rental 23 Buitengracht Street, • Airport handling service • Dry cleaning Cape Town City Centre, 8000 Telephone: +27 21 492 0404 Meeting spaces Email: capetown.reservations@ 5 conference rooms in total catering for up to 140 delegates. The venues can be tsogosun.com confi gured to host a range of occasions like intimate boardroom meetings, cocktail GPS Coordinates: -33.919122 S / 18.419020 E functions, workshops, seminars, training sessions, conferences as well as product launches. -

Driftsands Nature Reserve Complex PAMP

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Driftsands Nature Reserve is situated on the Cape Flats, approximately 25 km east of Cape Town on the National Route 2, in the Western Cape Province. The reserve is situated adjacent to the Medical Research Centre in Delft and is bounded by highways and human settlement on all sides. Driftsands is bound in the northwest by the R300 and the National Route 2 and Old Faure road in the south. The northern boundary is bordered by private landowners, while the eastern boundary is formed by Mfuleni Township. The Nature Reserve falls within the City of Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality. The reserve experiences a Mediterranean-type climate with warm dry summers, and cool wet winter seasons. Gale force winds from the south east prevail during the summer months, while during the winter months, north westerly winds bring rain. Driftsands Nature Reserve represents of one of the largest remaining remnants of intact Cape Flats Dune Strandveld which is classified as Endangered, and harbours at least two Endangered Cape Flats endemics, Muraltia mitior and Passerina paludosa. The Kuils River with associated floodplain wetlands, dune strandveld depressions and seeps are representative of a wetland type that has been subjected to high cumulative loss, and provides regulatory ecosystem services such as flood attenuation, ground water recharge/discharge and water quality improvement. The site provides access for cultural and/or religious practices and provides opportunities for quality curriculum based environmental education. Driftsands Nature Reserve is given the highest priority rating within the Biodiversity Network (BioNet), the fine scale conservation plan for the City of Cape Town. -

Cape Town's Failure to Redistribute Land

CITY LEASES CAPE TOWN’S FAILURE TO REDISTRIBUTE LAND This report focuses on one particular problem - leased land It is clear that in order to meet these obligations and transform and narrow interpretations of legislation are used to block the owned by the City of Cape Town which should be prioritised for our cities and our society, dense affordable housing must be built disposal of land below market rate. Capacity in the City is limited redistribution but instead is used in an inefficient, exclusive and on well-located public land close to infrastructure, services, and or non-existent and planned projects take many years to move unsustainable manner. How is this possible? Who is managing our opportunities. from feasibility to bricks in the ground. land and what is blocking its release? How can we change this and what is possible if we do? Despite this, most of the remaining well-located public land No wonder, in Cape Town, so little affordable housing has been owned by the City, Province, and National Government in Cape built in well-located areas like the inner city and surrounds since Hundreds of thousands of families in Cape Town are struggling Town continues to be captured by a wealthy minority, lies empty, the end of apartheid. It is time to review how the City of Cape to access land and decent affordable housing. The Constitution is or is underused given its potential. Town manages our public land and stop the renewal of bad leases. clear that the right to housing must be realised and that land must be redistributed on an equitable basis. -

Special Schools

Province District Name PrimaryDisability Postadd1 PhysAdd1 Telephone Numbers Fax Numbers Cell E_Mail No. of Learners No. of Educators Western Cape Metro South Education District Agape School For The CP CP & Physical disability P.O. Box23, Mitchells Plain, 7785 Cnr Sentinel and Yellowwood Tafelsig, Mitchells Plain 213924162 213925496 [email protected] 213 23 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Alpha School Autism Spectrum Dis order P.O Box 48, Woodstock, 7925 84 Palmerston Road Woodstock 214471213 214480405 [email protected] 64 12 Western Cape Metro East Education District Alta Du Toit School Intellectual disability Private Bag x10, Kuilsriver, 7579 Piet Fransman Street, Kuilsriver 7580 219034178 219036021 [email protected] 361 30 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Astra School For Physi Physical disability P O Box 21106, Durrheim, 7490 Palotti Road, Montana 7490 219340155 219340183 0835992523 [email protected] 321 35 Western Cape Metro North Education District # Athlone School For The Blind Visual Impairment Private BAG x1, Kasselsvlei Athlone Street Beroma, Bellville South 7533 219512234 219515118 0822953415 [email protected] 363 38 Western Cape Metro North Education District Atlantis School Of Skills MMH Private Bag X1, Dassenberg, Atlantis, 7350 Gouda Street Westfleur, Atlantis 7349 0215725022/3/4 215721538 [email protected] 227 15 Western Cape Metro Central Education District Batavia Special School MMH P.O Box 36357, Glosderry, 7702 Laurier Road Claremont 216715110 216834226 -

Revolution for Neoliberalism in a South African Township Annika Teppo, Myriam Houssay-Holzschuch

GugulethuTM: revolution for neoliberalism in a South African township Annika Teppo, Myriam Houssay-Holzschuch To cite this version: Annika Teppo, Myriam Houssay-Holzschuch. GugulethuTM: revolution for neoliberalism in a South African township. Canadian Journal of African Studies / La Revue canadienne des études africaines, Taylor & Francis (Routledge), 2013, 47 (1), pp.51-74. 10.1080/00083968.2013.770592. hal-00834788 HAL Id: hal-00834788 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00834788 Submitted on 1 Jul 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Gugulethu™: revolution for neoliberalism in a South African township Annika Teppo12* and Myriam Houssay-Holzschuch3 Résumé Gugulethu™: la Révolution pour le néolibéralisme dans un township sud-africain. Cet article analyse l’impact de la ne olibé ralisat́ ion sur les pratiques spatiales post- apartheid dans le cas du centre commercial de Gugulethu, nouvellement construit au Cap. Cet impact est analyse ́ a` deux niveaux: tout d’abord, du point de vue des processus ne olibé raux́ eux-meˆme et de leur adaptabilite ́ a` l’environnement local; puis du point de vue du township lui-meˆ me, analysant ce qui rend cet environnement perme ablé - insistant notamment sur le roˆle de me diateurś locaux. -

In the High Court of South Africa Western Cape Division, Cape Town

SAFLII Note: Certain personal/private details of parties or witnesses have been redacted from this document in compliance with the law and SAFLII Policy IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA WESTERN CAPE DIVISION, CAPE TOWN REPORTABLE CASE NO: A 276/2017 In the matter between: FREDERICK WESTERHUIS First Appellant CATHERINE WESTERHUIS Second Appellant and JAN LAMBERTUS WESTERHUIS First Respondent JAN LAMBERTUS WESTERHUIS N.O. (In his capacity as the Executor in the Estate of the late John Westerhuis) Second Respondent DERICK ALEXANDER WESTERHUIS N.O. (In his capacity as the Executor in the Estate of the late John Westerhuis) Third Respondent JAN LAMBERTUS WESTERHUIS N.O. (In his capacity as the Executor in the 2 Estate of the late Hendrikus Westerhuis) Fourth Respondent PATRICIA WESTERHUIS Fifth Respondent MARELIZE VAN DER MESCHT Sixth Respondent Coram: Erasmus, Gamble and Parker JJ. Date of Hearing: 20 April 2018. Date of Judgment: 27 June 2018. JUDGMENT DELIVERED ON WEDNESDAY 27 JUNE 2018 ____________________________________________________________________ GAMBLE, J: INTRODUCTION [1] In the aftermath of the Second World War there was a large migration of European refugees to various parts of the world, including South Africa. Amongst that number were Mr. Hendrikus Westerhuis and his wife, Trish, her sister Ms. Jannetje Haasnoot and her husband who was known as “Hug” Haasnoot. The Westerhuis and Haasnoot families first shared a communal home in the Cape Town suburb of Claremont and later moved to Vredehoek on the slopes of Devil’s Peak where they lived in adjacent houses. The Haasnoots stayed at […]3 V. Avenue and the Westerhuis’ at number […]5. -

Fact Sheet – Cape Town, South Africa Information Sourced at Population About 3.5-Million People Li

Fact Sheet – Cape Town, South Africa Information sourced at http://www.capetown.travel/ Population About 3.5-million people live in Cape Town, South Africa's second most-populated city. Time Cape Town lies in the GMT +2 time zone and does not have daylight saving time. Area South Africa is a large country, of 2 455km2(948mi2). Government Mayor of Cape Town: Patricia de Lille (Democratic Alliance) Premier of the Western Cape: Helen Zille (Democratic Alliance) Cape Town is the legislative capital of South Africa South Africa's Parliament sits in Cape Town History Cape Town was officially founded in 1652 when Jan van Riebeeck of the Dutch East India Company based in The Netherlands arrived to set up a halfway point for ships travelling to the East. Portuguese explorers arrived in the Cape in the 15th Century and Khoisan people inhabited the area prior to European arrival. Electricity South Africa operates on a 220/230V AC system and plugs have three round prongs. Telephone Country code: 0027 City code: 021 Entrance Visa requirements depend on nationality, but all foreign visitors are required to hold a valid passport. South Africa requires a valid yellow fever certificate from all foreign visitors and citizens over 1 year of age travelling from an infected area or having been in transit through infected areas. For visa requirements, please contact your nearest South African diplomatic mission. Fast facts Cape Town is the capital of the Western Cape. The city‟s motto is “Spes Bona”, which is Latin for “good hope”. Cape Town is twinned with London, Buenos Aires, Nice, San Francisco and several other international cities. -

R Conradie Orcid.Org 0000-0002-8653-4702

Influence of the invasive fish, Gambusia affinis, on amphibians in the Western Cape R Conradie orcid.org 0000-0002-8653-4702 Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Zoology at the North-West University Supervisor: Prof LH du Preez Co-supervisor: Prof AE Channing Graduation May 2018 23927399 “The whole land is made desolate, but no man lays it to heart.” JEREMIAH 12:11 i DECLARATION I, Roxanne Conradie, declare that this dissertation is my own, unaided work, except where otherwise acknowledged. It is being submitted for the degree of M.Sc. to the North-West University, Potchefstroom. It has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. ____________________ (Roxanne Conradie) ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the following persons and organisations, without whose assistance this study would not have been possible: My supervisor Prof. Louis du Preez and co-supervisor Prof. Alan Channing, for guidance, advice, support, and encouragement throughout the duration of this study. Prof Louis, your passion for the biological sciences has been an inspiration to me since undergraduate Zoology classes five years ago. Prof Alan, you were a vital pillar of support for me in the Cape and I am incredibly grateful towards you. Thank you both for all the time and effort you have put into helping me with my work, for all your honest and detailed advice, as well as practical help. It is truly a privilege to have had such outstanding biologists as my mentors. My husband Louis Conradie, for offering up so many weekends in order to help me with fieldwork. -

The Great Green Outdoors

MAMRE CITY OF CAPE TOWN WORLD DESIGN CAPITAL CAPE TOWN 2014 ATLANTIS World Design Capital (WDC) is a biannual honour awarded by the International Council for Societies of Industrial Design (ICSID), to one city across the globe, to show its commitment to using design as a social, cultural and economic development tool. THE GREAT Cape Town Green Map is proud to have been included in the WDC 2014 Bid Book, 2014 SILWERSTROOMSTRAND and played host to the International ICSID judges visiting the city. 01 Design-led thinking has the potential to improve life, which is why Cape WORLD DESIGN CAPITAL GREEN OUTDOORS R27 Town’s World Design Capital 2014’s over-arching theme is ‘Live Design. Transform Life.’ Cape Town is defi nitively Green by Design. Our city is one of a few Our particular focus has become ‘Green by Design’ - projects and in the world with a national park and two World Heritage Sites products where environmental, social and cultural impacts inform (Table Mountain National Park and Robben Island) contained within design and aim to transform life. KOEBERG NATURE its boundaries. The Mother City is located in a biodiversity hot Green Map System accepted Cape Town’s RESERVE spot‚ the Cape Floristic Region, and is recognised globally for its new category and icon, created by Design extraordinarily rich and diverse fauna and fl ora. Infestation – the fi rst addition since 2008 to their internationally recognised set of icons. N www.capetowngreenmap.co.za Discover and experience Cape Town’s natural beauty and enjoy its For an overview of Cape Town’s WDC 2014 projects go to www.capetowngreenmap.co.za/ great outdoor lifestyle choices. -

13-17 July 2015 Name of School Surname Name Total

13-17 July 2015 Name of School Surname Name Total HS Porterville Breytenbach Elmarie Steynville Sek Carstens Liza-Mari Vooruitsig PS De Bruyn Johan HS Dirkie Uys De Vreye Leney HS Swartland Du Preez I Vooruitsig PS Engelbrecht Richard Stawelklip PS Faro Mathilda Willemsvallei PS Fortuin PM HS Swartland Gerber R HS Aurora Horne Susarah Schoon-spruit Sek Karstens Tashline Riebeek-Wes PS Mentoor Maurese Riebeek-Wes PS Mentoor Nicola Riebeek-Wes PS Nel Karen Schoon-spruit Sek Rinquest Jade Stawelklip PS Schaffers Brandon Wesbank Sek Strydom Steel Laurie Hugo PS Swart John Laurie Hugo PS Swart John Gary Wesbank Sek Van der Merwe Eunice Schoon-spruit Sek Van der Merwe Anneke Schoon-spruit Sek Van der Merwe Brynmor Steynville Sek Van Rooyen Rashonia HS Swartland Visser GJ Wesbank Sek Willemse Sharon Ashton PC (CW) Gqamana Luvuyo Ashton PC (CW) Magida Noxolo Van Cutsem (CW) Zondo Siphumuzile Van Cutsem (CW) Tose Vuyani, Masakheke HS (CW) Harmse Shaun Masakheke HS (CW) Basvi Stevin Paul Roos Gim Canaris Christine Vusisiswe Secondary Kula Phumla Vusisiswe Secondary Mthenjana Patrick Iingcinga Zethu Yame Mninawe Makapula Noji Nolubabalo Makupula Den Merg Diza Makupula Magwaca Nomfuneko Desmond Tutu Nqoyo Nompume-lelo Desmond Tutu Mbulawa Bukelwa Desmond Tutu Siduma Mandla Kayamandi HS Ngcwebo Ntombi Kayamandi HS Mpokeli Zanomzi Kayamandi HS Phinda Makapela Langeberg Williams Esther Langeberg Eksteen Henry Langeberg Munnik Melvyn De Kruine Sek April Yolandi Ilingellethu HS Mhambi Unathi Ilingellethu HS Mangcengeza Wandile Diazville HS Kaba Nomveliso