Constantine Rafinesque, a Flawed Genius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Wildflower Talk

Wildflower Talk These are a series of short articles written by Kristen Currin of Humble Roots Native Plant Nursery in Mosier, Oregon, featuring plants from around the Columbia Gorge. Each of these articles appeared in an issue of the Wasco County Soil and Water Conservation District’s newsletter, GROUNDWORK. I hope you enjoy them. All photos are courtesy of Kristen Currin. Please ask permission before using. www.humblerootsnursery.com Nothing in this document is to be construed as medical advice. A licensed herbalist should be consulted for proper identification and preparation before eating those plants designated as edible. Humble Roots Nursery nor the Conservation District are liable for improper consumption of plants listed in this document. INDEX Arnica, Heart-Leaf Glacier Lily Phlox, Cushion Bachelor Buttons Goldenrod Pineapple Weed Balsamroot Grass Widow Prairie Stars Bitterroot Indian Hemp Rabbitbrush (sp) Buckwheat, Arrowleaf Juniper Rabbitbrush, Gray Buckwheat, Snow Larkspur, Upland Rose, Wild California Poppy Kinnickinick Saxifrage Cattail Mariposa Lily Serviceberry Ceanothus Milkweed, Showy Shooting Star, Poet’s Chocolate Lily Miner’s Lettuce Sumac, Smooth Columbia Coreopsis Mugwort, Western Wapato Currant, Golden Native Shrubs Washington Lily Dutchman’s Breeches Nettle, Stinging Western Bunchberry Desert Parsley, Columbia Oceanspray Yellow Bee Plant Desert Parsley, Gray’s Oregon Grape Yellow Bells Elderberry, Blue Pearly Everlasting Yellow Star Thistle Gairdners Yampah Phantom Orchid 1 TOP Page Heart-leaf Arnica Arnica cordifolia Look for arnica's yellow flowers in spring. Arnica is an important native medicinal plant used topically to soothe sore muscles and sprains. A woodland plant and a good choice for the shady xeric garden. Bachelor Buttons, Cornflower Centaurea cyanus Many may think this beautiful blue flower is a native plant due to the fact that it dominates many of our meadows and is commonly sold in wildflower seed mixes. -

Pinery Provincial Park Vascular Plant List Flowering Latin Name Common Name Community Date

Pinery Provincial Park Vascular Plant List Flowering Latin Name Common Name Community Date EQUISETACEAE HORSETAIL FAMILY Equisetum arvense L. Field Horsetail FF Equisetum fluviatile L. Water Horsetail LRB Equisetum hyemale L. ssp. affine (Engelm.) Stone Common Scouring-rush BS Equisetum laevigatum A. Braun Smooth Scouring-rush WM Equisetum variegatum Scheich. ex Fried. ssp. Small Horsetail LRB Variegatum DENNSTAEDIACEAE BRACKEN FAMILY Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn Bracken-Fern COF DRYOPTERIDACEAE TRUE FERN FAMILILY Athyrium filix-femina (L.) Roth ssp. angustum (Willd.) Northeastern Lady Fern FF Clausen Cystopteris bulbifera (L.) Bernh. Bulblet Fern FF Dryopteris carthusiana (Villars) H.P. Fuchs Spinulose Woodfern FF Matteuccia struthiopteris (L.) Tod. Ostrich Fern FF Onoclea sensibilis L. Sensitive Fern FF Polystichum acrostichoides (Michaux) Schott Christmas Fern FF ADDER’S-TONGUE- OPHIOGLOSSACEAE FERN FAMILY Botrychium virginianum (L.) Sw. Rattlesnake Fern FF FLOWERING FERN OSMUNDACEAE FAMILY Osmunda regalis L. Royal Fern WM POLYPODIACEAE POLYPODY FAMILY Polypodium virginianum L. Rock Polypody FF MAIDENHAIR FERN PTERIDACEAE FAMILY Adiantum pedatum L. ssp. pedatum Northern Maidenhair Fern FF THELYPTERIDACEAE MARSH FERN FAMILY Thelypteris palustris (Salisb.) Schott Marsh Fern WM LYCOPODIACEAE CLUB MOSS FAMILY Lycopodium lucidulum Michaux Shining Clubmoss OF Lycopodium tristachyum Pursh Ground-cedar COF SELAGINELLACEAE SPIKEMOSS FAMILY Selaginella apoda (L.) Fern. Spikemoss LRB CUPRESSACEAE CYPRESS FAMILY Juniperus communis L. Common Juniper Jun-E DS Juniperus virginiana L. Red Cedar Jun-E SD Thuja occidentalis L. White Cedar LRB PINACEAE PINE FAMILY Larix laricina (Duroi) K. Koch Tamarack Jun LRB Pinus banksiana Lambert Jack Pine COF Pinus resinosa Sol. ex Aiton Red Pine Jun-M CF Pinery Provincial Park Vascular Plant List 1 Pinery Provincial Park Vascular Plant List Flowering Latin Name Common Name Community Date Pinus strobus L. -

Selected Wildflowers of the Modoc National Forest Selected Wildflowers of the Modoc National Forest

United States Department of Agriculture Selected Wildflowers Forest Service of the Modoc National Forest An introduction to the flora of the Modoc Plateau U.S. Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region i Cover image: Spotted Mission-Bells (Fritillaria atropurpurea) ii Selected Wildflowers of the Modoc National Forest Selected Wildflowers of the Modoc National Forest Modoc National Forest, Pacific Southwest Region U.S. Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region iii Introduction Dear Visitor, e in the Modoc National Forest Botany program thank you for your interest in Wour local flora. This booklet was prepared with funds from the Forest Service Celebrating Wildflowers program, whose goals are to serve our nation by introducing the American public to the aesthetic, recreational, biological, ecological, medicinal, and economic values of our native botanical resources. By becoming more thoroughly acquainted with local plants and their multiple values, we hope to consequently in- crease awareness and understanding of the Forest Service’s management undertakings regarding plants, including our rare plant conservation programs, invasive plant man- agement programs, native plant materials programs, and botanical research initiatives. This booklet is a trial booklet whose purpose, as part of the Celebrating Wildflowers program (as above explained), is to increase awareness of local plants. The Modoc NF Botany program earnestly welcomes your feedback; whether you found the book help- ful or not, if there were too many plants represented or too few, if the information was useful to you or if there is more useful information that could be added, or any other comments or concerns. Thank you. Forest J. R. Gauna Asst. -

Riverside State Park

Provisonal Report Rare Plant and Vegetation Survey of Riverside State Park Pacific Biodiversity Institute 2 Provisonal Report Rare Plant and Vegetation Survey of Riverside State Park Peter H. Morrison [email protected] George Wooten [email protected] Juliet Rhodes [email protected] Robin O’Quinn, Ph.D. [email protected] Hans M. Smith IV [email protected] January 2009 Pacific Biodiversity Institute P.O. Box 298 Winthrop, Washington 98862 509-996-2490 Recommended Citation Morrison, P.H., G. Wooten, J. Rhodes, R. O’Quinn and H.M. Smith IV, 2008. Provisional Report: Rare Plant and Vegetation Survey of Riverside State Park. Pacific Biodiversity Institute, Winthrop, Washington. 433 p. Acknowledgements Diana Hackenburg and Alexis Monetta assisted with entering and checking the data we collected into databases. The photographs in this report were taken by Peter Morrison, Robin O’Quinn, Geroge Wooten, and Diana Hackenburg. Project Funding This project was funded by the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission. 3 Executive Summary Pacific Biodiversity Institute (PBI) conducted a rare plant and vegetation survey of Riverside State Park (RSP) for the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission (WSPRC). RSP is located in Spokane County, Washington. A large portion of the park is located within the City of Spokane. RSP extends along both sides of the Spokane River and includes upland areas on the basalt plateau above the river terraces. The park also includes the lower portion of the Little Spokane River and adjacent uplands. The park contains numerous trails, campgrounds and other recreational facilities. The park receives a tremendous amount of recreational use from the nearby population. -

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY BIBLIOGRAPHY Ackerfield, J., and J. Wen. 2002. A morphometric analysis of Hedera L. (the ivy genus, Araliaceae) and its taxonomic implications. Adansonia 24: 197-212. Adams, P. 1961. Observations on the Sagittaria subulata complex. Rhodora 63: 247-265. Adams, R.M. II, and W.J. Dress. 1982. Nodding Lilium species of eastern North America (Liliaceae). Baileya 21: 165-188. Adams, R.P. 1986. Geographic variation in Juniperus silicicola and J. virginiana of the Southeastern United States: multivariant analyses of morphology and terpenoids. Taxon 35: 31-75. ------. 1995. Revisionary study of Caribbean species of Juniperus (Cupressaceae). Phytologia 78: 134-150. ------, and T. Demeke. 1993. Systematic relationships in Juniperus based on random amplified polymorphic DNAs (RAPDs). Taxon 42: 553-571. Adams, W.P. 1957. A revision of the genus Ascyrum (Hypericaceae). Rhodora 59: 73-95. ------. 1962. Studies in the Guttiferae. I. A synopsis of Hypericum section Myriandra. Contr. Gray Herbarium Harv. 182: 1-51. ------, and N.K.B. Robson. 1961. A re-evaluation of the generic status of Ascyrum and Crookea (Guttiferae). Rhodora 63: 10-16. Adams, W.P. 1973. Clusiaceae of the southeastern United States. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 89: 62-71. Adler, L. 1999. Polygonum perfoliatum (mile-a-minute weed). Chinquapin 7: 4. Aedo, C., J.J. Aldasoro, and C. Navarro. 1998. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sections Batrachioidea and Divaricata (Geraniaceae). Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 85: 594-630. Affolter, J.M. 1985. A monograph of the genus Lilaeopsis (Umbelliferae). Systematic Bot. Monographs 6. Ahles, H.E., and A.E. -

Plants for Bats

Suggested Native Plants for Bats Nectar Plants for attracting moths:These plants are just suggestions based onfloral traits (flower color, shape, or fragrance) for attracting moths and have not been empirically tested. All information comes from The Lady Bird Johnson's Wildflower Center's plant database. Plant names with * denote species that may be especially high value for bats (based on my opinion). Availability denotes how common a species can be found within nurseries and includes 'common' (found in most nurseries, such as Rainbow Gardens), 'specialized' (only available through nurseries such as Medina Nursery, Natives of Texas, SA Botanical Gardens, or The Nectar Bar), and 'rare' (rarely for sale but can be collected from wild seeds or cuttings). All are native to TX, most are native to Bexar. Common Name Scientific Name Family Light Leaves Water Availability Notes Trees: Sabal palm * Sabal mexicana Arecaceae Sun Evergreen Moderate Common Dead fronds for yellow bats Yaupon holly Ilex vomitoria Aquifoliaceae Any Evergreen Any Common Possumhaw is equally great Desert false willow Chilopsis linearis Bignoniaceae Sun Deciduous Low Common Avoid over-watering Mexican olive Cordia boissieri Boraginaceae Sun/Part Evergreen Low Common Protect from deer Anacua, sandpaper tree * Ehretia anacua Boraginaceae Sun Evergreen Low Common Tough evergreen tree Rusty blackhaw * Viburnum rufidulum Caprifoliaceae Partial Deciduous Low Specialized Protect from deer Anacacho orchid Bauhinia lunarioides Fabaceae Partial Evergreen Low Common South Texas species -

Garden of the Month APRIL the NATIVE PLANT GARDEN Spring Comes Early to the Native Plant Garden

Garden of the Month APRIL THE NATIVE PLANT GARDEN Spring comes early to the Native Plant garden. With our Mediterranean climate of wet winters and dry summers, most of our native flowers bloom in spring and are dormant by July. The blossoms of June plum (Oemleria cerasiformis) (1), gummy gooseberry (Ribes lobbii)(2) and satin flower (Olsynium douglasii)(3) have been and gone. Now the second wave of bloom is underway, with fawn lilies (Erythronium oregonum, E. revolutum)(4), camas (Camassia quamash, C. leichtlinii)(5), chocolate lilies (Fritillaria affinis)(6), sea blush (Plectritis congesta)(7),, shooting star (Dodecatheon hendersonii)(8), skunk cabbage (Lysichiton americanum)(9) and red-flowering currant (Ribes sanguinium) (10) in flower. Trillium (Trillium ovatum)(11) and coast penstemon (Penstemon serrulatus)(12) will soon emerge. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 THE GARRY OAK MEADOW FLOWER GARDEN You are welcome to visit the Garry Oak Meadow Flower Garden, located down the hill above the lake, framed by the large Douglas Fir trees and the great lawn. This ethnobotanical garden is a loop of the larger W̱ SÁNEĆ Ethnobotanical Trail, you could follow the trail signs or just wander past the round Gathering Place to find it. All the plants species in this garden are native to this area and represent the Garry oak ecosystem. Most of them have medicinal, food or technological values. CONTINUED OVERLEAF The Gardens at HCP, 505 Quayle Road, Saanich, V9E 2 J7 | Tel: 250 479 6162 | www.hcp.ca Garden of the Month THE GARRY OAK MEADOW FLOWER GARDEN (CONTINUED) Just as we pass the Spring Equinox and the Spring season begins, the Garry oak Meadow Flower Garden wakes up. -

Tribe Species Secretory Structure Compounds Organ References Incerteae Sedis Alphitonia Sp. Epidermis, Idioblasts, Cavities

Table S1. List of secretory structures found in Rhamanaceae (excluding the nectaries), showing the compounds and organ of occurrence. Data extracted from the literature and from the present study (species in bold). * The mucilaginous ducts, when present in the leaves, always occur in the collenchyma of the veins, except in Maesopsis, where they also occur in the phloem. Tribe Species Secretory structure Compounds Organ References Epidermis, idioblasts, Alphitonia sp. Mucilage Leaf (blade, petiole) 12, 13 cavities, ducts Epidermis, ducts, Alphitonia excelsa Mucilage, terpenes Flower, leaf (blade) 10, 24 osmophores Glandular leaf-teeth, Flower, leaf (blade, Ceanothus sp. Epidermis, hypodermis, Mucilage, tannins 12, 13, 46, 73 petiole) idioblasts, colleters Ceanothus americanus Idioblasts Mucilage Leaf (blade, petiole), stem 74 Ceanothus buxifolius Epidermis, idioblasts Mucilage, tannins Leaf (blade) 10 Ceanothus caeruleus Idioblasts Tannins Leaf (blade) 10 Incerteae sedis Ceanothus cordulatus Epidermis, idioblasts Mucilage, tannins Leaf (blade) 10 Ceanothus crassifolius Epidermis; hypodermis Mucilage, tannins Leaf (blade) 10, 12 Ceanothus cuneatus Epidermis Mucilage Leaf (blade) 10 Glandular leaf-teeth Ceanothus dentatus Lipids, flavonoids Leaf (blade) (trichomes) 60 Glandular leaf-teeth Ceanothus foliosus Lipids, flavonoids Leaf (blade) (trichomes) 60 Glandular leaf-teeth Ceanothus hearstiorum Lipids, flavonoids Leaf (blade) (trichomes) 60 Ceanothus herbaceus Idioblasts Mucilage Leaf (blade, petiole), stem 74 Glandular leaf-teeth Ceanothus -

Checklist Flora of the Former Carden Township, City of Kawartha Lakes, on 2016

Hairy Beardtongue (Penstemon hirsutus) Checklist Flora of the Former Carden Township, City of Kawartha Lakes, ON 2016 Compiled by Dale Leadbeater and Anne Barbour © 2016 Leadbeater and Barbour All Rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or database, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, without written permission of the authors. Produced with financial assistance from The Couchiching Conservancy. The City of Kawartha Lakes Flora Project is sponsored by the Kawartha Field Naturalists based in Fenelon Falls, Ontario. In 2008, information about plants in CKL was scattered and scarce. At the urging of Michael Oldham, Biologist at the Natural Heritage Information Centre at the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Dale Leadbeater and Anne Barbour formed a committee with goals to: • Generate a list of species found in CKL and their distribution, vouchered by specimens to be housed at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, making them available for future study by the scientific community; • Improve understanding of natural heritage systems in the CKL; • Provide insight into changes in the local plant communities as a result of pressures from introduced species, climate change and population growth; and, • Publish the findings of the project . Over eight years, more than 200 volunteers and landowners collected almost 2000 voucher specimens, with the permission of landowners. Over 10,000 observations and literature records have been databased. The project has documented 150 new species of which 60 are introduced, 90 are native and one species that had never been reported in Ontario to date. -

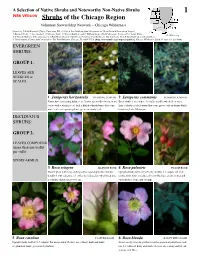

Shrubs of the Chicago Region

A Selection of Native Shrubs and Noteworthy Non-Native Shrubs 1 WEB VERSION Shrubs of the Chicago Region Volunteer Stewardship Network – Chicago Wilderness Photos by: © Paul Rothrock (Taylor University, IN), © John & Jane Balaban ([email protected]; North Branch Restoration Project), © Kenneth Dritz, © Sue Auerbach, © Melanie Gunn, © Sharon Shattuck, and © William Burger (Field Museum). Produced by: Jennie Kluse © vPlants.org and Sharon Shattuck, with assistance from Ken Klick (Lake County Forest Preserve), Paul Rothrock, Sue Auerbach, John & Jane Balaban, and Laurel Ross. © Environment, Culture and Conservation, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605 USA. [http://www.fmnh.org/temperateguides/]. Chicago Wilderness Guide #5 version 1 (06/2008) EVERGREEN SHRUBS: GROUP 1. LEAVES ARE NEEDLES or SCALES. 1 Juniperus horizontalis TRAILING JUNIPER: 2 Juniperus communis COMMON JUNIPER: Plants have a creeping habit; some leaves are needles but most are Erect shrub or tree (up to 3 m tall); needles whorled on stem; scales with a whitish coat; fruit a bluish-whitish berry-like cone; fruit a bluish or black berry-like cone; grows only in dunes/bluffs male cones on separate plants; grows in sandy soils. bordering Lake Michigan. DECIDUOUS SHRUBS: GROUP 2. LEAVES COMPOUND (more than one leaflet per stalk). STEMS ARMED. 3 Rosa setigera ILLINOIS ROSE: 4 Rosa palustris SWAMP ROSE: Mature plant with long-arching stems; sparse prickles; leaflets Upright shrub; stems very thorny; leaflets 5-7; sepals fall from usually 3, but sometimes 5; styles (female pollen tube) fused into mature fruit; fruit smooth, red berry-like hips; grows in wet and a column; stipules narrow to tip. open ditches, bogs, and swamps. -

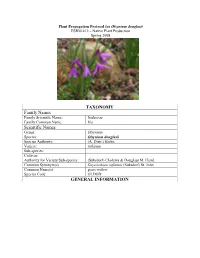

Draft Plant Propagation Protocol

Plant Propagation Protocol for Olsynium douglasii ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production Spring 2008 TAXONOMY Family Names Family Scientific Name: Iridaceae Family Common Name: Iris Scientific Names Genus: Olsynium Species: Olsynium douglasii Species Authority: (A. Dietr.) Bickn. Variety: inflatum Sub-species: Cultivar: Authority for Variety/Sub-species: (Suksdorf) Cholewa & Douglass M. Hend. Common Synonym(s) Sisyrinchium inflatum (Suksdorf) St. John Common Name(s): grass widow Species Code: OLDOD GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical range: Ecological distribution: Native to open, vernally moist places from shrub- steppe to open ponderosa pine forests east of the Cascade Mountains of southern British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, extending into Idaho, Utah, and northern Nevada (Skinner 2008). Coastal bluffs, prairies, open rocky areas, oak and ponderosa pine woodlands, sagebrush and juniper desert, where moist in early spring (Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture 2006). Climate and elevation range: Between 3000 and 6000 feet (Calflora 2004). Local habitat: Sagebrush Scrub, Northern Juniper Woodland, Northern Oak Woodland, Foothill Woodland, Yellow Pine Forest (Califlora 2004). Plant characteristics: Not invasive, perennial, forb/herb, no toxicity, moderate growth rate, not fire resistant. PROPAGATION DETAILS Ecotype: North of Pullman, Washington (Skinner 2008). Propagation Goal: Plants (Skinner 2008). Propagation Method: Seed (Skinner 2008). Product Type: Container (plug) (Skinner 2008). Stock Type: 10 cu. In (Skinner 2008). Time to Grow (from seeding until 2 Years (Skinner 2008). plants are ready to be outplanted): Target Specifications: Tight root plug in container (Skinner 2008). Propagule Collection: Fruit is a capsule. Seed is reddish brown in color. Seed is collected when the capsules begin to split in July and is stored in paper bags or envelopes at room temperature until cleaned (Skinner 2008).