Douglas R. White*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AH16 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health

AH16 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health www.racgp.org.au Healthy Profession. Healthy Australia. AH16 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health Disclaimer The information set out in this publication is current at the date of first publication and is intended for use as a guide of a general nature only and may or may not be relevant to particular patients or circumstances. Nor is this publication exhaustive of the subject matter. Persons implementing any recommendations contained in this publication must exercise their own independent skill or judgement or seek appropriate professional advice relevant to their own particular circumstances when so doing. Compliance with any recommendations cannot of itself guarantee discharge of the duty of care owed to patients and others coming into contact with the health professional and the premises from which the health professional operates. Accordingly, The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) and its employees and agents shall have no liability (including without limitation liability by reason of negligence) to any users of the information contained in this publication for any loss or damage (consequential or otherwise), cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information contained in this publication and whether caused by reason of any error, negligent act, omission or misrepresentation in the information. Recommended citation The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Curriculum for Australian General Practice 2016 – AH16 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. East Melbourne, Vic: RACGP, 2016. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 100 Wellington Parade East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Australia Tel 03 8699 0510 Fax 03 9696 7511 www.racgp.org.au Published May 2016 © The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners We recognise the traditional custodians of the land and sea on which we work and live. -

Mongolian Transport Policy on Operational Connectivity for Integrated Intermodal Transport and Logistics in the Region

MONGOLIAN TRANSPORT POLICY ON OPERATIONAL CONNECTIVITY FOR INTEGRATED INTERMODAL TRANSPORT AND LOGISTICS IN THE REGION Forum on Sustainable transport connectivity between Europe and Asia in the framework of the 62 session of UNECE and Working party on Intermodal transport and Logistics 30 OCTOBER 2019, GENEVA, SWITZERLAND Ministry of Road and Transport Development of MongoliaMongolia Page 1 CONTENT General information Legal framework and Intergovernmental Agreements Operational practice along international corridors Facilitation measures for international railway transport Vision and challenges MinistryMinistry of of Road Road and and Transport Transport Development Development of of Mongolia Mongolia – Regional MeetingUNESCAP Page 2 Mongolia is one of largest landlocked countries in the world, with a territory extending over 1.5 million square kilometers. It is bordered by Peoples Republic of China on three sides, to the East, South and West and by Russian Federation to the North. The country is rich in a variety of mineral resources and has substantial livestock herds, ranking first in per capita ownership in the world. Mongolia is a sparsely populated country, with a population of around 3.2 million, with population density of 2 persons per square kilometers. However, more than 60 percent of the population live in urban area. The construction of new roads and the maintenance of existing ones are being given high priority of the Mongolian Government. As part of the Government of Mongolia’s 2016-2020 action plan road and transport sector’s objective is to expand and develop transport and logistics network that supports economic improvement, meet social needs and requirements and provides safe and comfortable service. -

Statement by Mr. Abduvohid Karimov, Chairman of The

EF.DEL/39/06 22 May 2006 ENGLISH Original: RUSSIAN STATEMENT BY MR. ABDUVOHID KARIMOV, CHAIRMAN OF THE STATE COMMITTEE FOR ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AND FORESTRY OF THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN, AT THE FOURTEENTH MEETING OF THE OSCE ECONOMIC FORUM Prague, 22 to 24 May 2006 Transport development and the environment in the Republic of Tajikistan Mr. Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen, Allow me on behalf of the Government of the Republic of Tajikistan to express our sincere gratitude to the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe for the invitation to this meeting and to the OSCE Centre in Dushanbe in particular for helping us to participate in the work of the Fourteenth Meeting of the OSCE Economic Forum to examine transport development with a view to enhancing regional economic co-operation and stability and its impact on the environment. Regional and international environmental co-operation is one of the main focuses of the Government of the Republic of Tajikistan, increasing the effectiveness of many decisions adopted and helping in the implementation of practical measures to improve the state of the environment in our country and in the region. As you are aware, the Republic of Tajikistan played an active role in the preparation of the international conference held in Dushanbe on 7 and 8 November 2005, and representatives from Tajikistan also took part in the first stage of the Forum in Vienna in January of this year. This once again confirms Tajikistan’s desire to support an international policy of development and to create favourable conditions for its implementation in our country and in the region. -

Pin Information for the Stratix IV GT EP4S40G2 Device

Pin Information for the Stratix® IV GT EP4S40G2 Device Version 1.2 Note (1) Dynamic Bank Configuration Dedicated Tx/Rx Emulated LVDS OCT DQS for X4 for DQS for X8/X9 for DQS for X16/ X18 for Number VREF Pin Name/Function Optional Function(s) Function Channel Output Channel F1517 Support F1517 F1517 F1517 1A TDI TDI J29 No 1A TMS TMS N27 No 1A TRST TRST A32 No 1A TCK TCK G30 No 1A TDO TDO F30 No 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_TX_L1n DIFFOUT_L1n K29 Yes 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_TX_L1p DIFFOUT_L1p L29 Yes 1A VREFB1AN0 IO RDN1A DIFFIO_RX_L1n DIFFOUT_L2n C34 Yes 1A VREFB1AN0 IO RUP1A DIFFIO_RX_L1p DIFFOUT_L2p D34 Yes 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_TX_L2n DIFFOUT_L3n J30 Yes DQ1L DQ1L DQ1L 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_TX_L2p DIFFOUT_L3p K30 Yes DQ1L DQ1L DQ1L 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_RX_L2n DIFFOUT_L4n C31 Yes DQSn1L DQ1L DQ1L 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_RX_L2p DIFFOUT_L4p D31 Yes DQS1L DQ1L/CQn1L DQ1L 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_TX_L3n DIFFOUT_L5n M28 Yes DQ1L DQ1L DQ1L 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_TX_L3p DIFFOUT_L5p N28 Yes DQ1L DQ1L DQ1L NC C35 Yes NC D35 Yes 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_TX_L4n DIFFOUT_L7n H32 Yes DQ2L DQ1L DQ1L 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_TX_L4p DIFFOUT_L7p J32 Yes DQ2L DQ1L DQ1L 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_RX_L4n DIFFOUT_L8n B32 Yes DQ2L DQ1L DQ1L 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_RX_L4p DIFFOUT_L8p C32 Yes DQ2L DQ1L DQ1L 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_TX_L5n DIFFOUT_L9n M31 Yes DQ3L DQ2L DQ1L 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_TX_L5p DIFFOUT_L9p N31 Yes DQ3L DQ2L DQ1L 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_RX_L5n DIFFOUT_L10n C33 Yes DQSn3L DQ2L DQSn1L/DQ1L 1A VREFB1AN0 IO DIFFIO_RX_L5p DIFFOUT_L10p D33 Yes DQS3L DQ2L/CQn2L -

Structure of ATP Synthase from Paracoccus Denitrificans Determined by X-Ray Crystallography at 4.0 Å Resolution

Structure of ATP synthase from Paracoccus denitrificans determined by X-ray crystallography at 4.0 Å resolution Edgar Morales-Riosa, Martin G. Montgomerya, Andrew G. W. Leslieb,1, and John E. Walkera,1 aMedical Research Council Mitochondrial Biology Unit, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Cambridge CB2 0XY, United Kingdom; and bMedical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Cambridge CB2 0QH, United Kingdom Contributed by John E. Walker, September 4, 2015 (sent for review July 28, 2015; reviewed by Stanley D. Dunn, Robert H. Fillingame, and Dale Wigley) The structure of the intact ATP synthase from the α-proteobacterium mitochondrial enzyme that have no known role in catalysis (2). Paracoccus denitrificans ζ , inhibited by its natural regulatory -protein, Structures have been described of the F1 domains of the enzymes has been solved by X-ray crystallography at 4.0 Å resolution. The from Escherichia coli (10, 11), Caldalkalibacillus thermarum (12), ζ-protein is bound via its N-terminal α-helix in a catalytic interface in and Geobacillus stearothermophilus (formerly Bacillus PS3) (13); of the F1 domain. The bacterial F1 domain is attached to the membrane the α3β3-subcomplex of the F1 domain from G. stearothermophilus domain by peripheral and central stalks. The δ-subunit component of (14); and of isolated c-rings from the rotors of several species (15– the peripheral stalk binds to the N-terminal regions of two α-subunits. 19). There is also structural information on the peripheral stalk The stalk extends via two parallel long α-helices, one in each of the region of the F-ATPase from E. -

Dating of Remains of Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens from Anatolian Region by ESR-US Combined Methods: Preliminary Results

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 5, ISSUE 05, MAY 2016 ISSN 2277-8616 Dating Of Remains Of Neanderthals And Homo Sapiens From Anatolian Region By ESR-US Combined Methods: Preliminary Results Samer Farkh, Abdallah Zaiour, Ahmad Chamseddine, Zeinab Matar, Samir Farkh, Jamal Charara, Ghayas Lakis, Bilal Houshaymi, Alaa Hamze, Sabine Azoury Abstract: We tried in the present study to apply the electron spin resonance method (ESR) combined with uranium-series method (US), for dating fossilized human teeth and found valuable archaeological sites such as Karain Cave in Anatolia. Karain Cave is a crucial site in a region that has yielded remains of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, our direct ancestors. The dating of these remains allowed us to trace the history, since the presence of man on earth. Indeed, Anatolia in Turkey is an important region of the world because it represents a passage between Africa, the Middle East and Europe. Our study was conducted on faunal teeth found near human remains. The combination of ESR and US data on the teeth provides an understanding of their complex geochemical evolution and get better estimated results. Our samples were taken from the central cutting where geological layers are divided into archaeological horizons each 10 cm. The AH4 horizon of I.3 layer, which represents the boundary between the Middle Paleolithic and Upper Paleolithic, is dated to 29 ± 4 ka by the ESR-US model. Below, two horizons AH6 and AH8 in the same layer I.4 are dated respectively 40 ± 6 and 45 ± 7 ka using the ESR-US model. -

Pin Information for the Intel® Stratix®10 1SG10M Device Version: 2020-10-22

Pin Information for the Intel® Stratix®10 1SG10M Device Version: 2020-10-22 TYPE BANK NF74 Package Transceiver I/O 1CU10 28 Transceiver I/O 1CU20 28 Transceiver I/O 1DU10 12 Transceiver I/O 1DU20 12 Transceiver I/O 1EU10 20 Transceiver I/O 1EU20 20 Transceiver I/O 1KU12 28 Transceiver I/O 1KU22 28 Transceiver I/O 1LU12 12 Transceiver I/O 1LU22 12 Transceiver I/O 1MU12 20 Transceiver I/O 1MU22 20 LVDS I/O 2AU1 48 LVDS I/O 2AU2 48 LVDS I/O 2BU1 48 LVDS I/O 2BU2 48 LVDS I/O 2CU1 48 LVDS I/O 2CU2 48 LVDS I/O 2FU1 48 LVDS I/O 2FU2 48 LVDS I/O 2GU1 48 LVDS I/O 2GU2 48 LVDS I/O 2HU1 48 LVDS I/O 2HU2 48 LVDS I/O 2IU1 48 LVDS I/O 2IU2 48 LVDS I/O 2JU1 48 LVDS I/O 2JU2 48 LVDS I/O 2KU1 48 LVDS I/O 2KU2 48 LVDS I/O 2LU1 48 LVDS I/O 2LU2 48 LVDS I/O 2MU1 48 LVDS I/O 2MU2 48 LVDS I/O 2NU1 48 LVDS I/O 2NU2 48 LVDS I/O 3AU1 48 LVDS I/O 3AU2 48 LVDS I/O 3BU1 48 LVDS I/O 3BU2 48 LVDS I/O 3CU1 48 LVDS I/O 3CU2 48 LVDS I/O 3DU1 48 LVDS I/O 3DU2 48 LVDS I/O 3EU1 48 LVDS I/O 3EU2 48 LVDS I/O 3FU1 48 PT- 1SG10M Copyright © 2020 Intel Corp IO Resource Count Page 1 of 49 Pin Information for the Intel® Stratix®10 1SG10M Device Version: 2020-10-22 TYPE BANK NF74 Package LVDS I/O 3FU2 48 LVDS I/O 3GU1 48 LVDS I/O 3GU2 48 LVDS I/O 3HU1 48 LVDS I/O 3HU2 48 LVDS I/O 3IU1 48 LVDS I/O 3IU2 48 LVDS I/O 3JU1 48 LVDS I/O 3JU2 48 LVDS I/O 3KU1 48 LVDS I/O 3KU2 48 LVDS I/O 3LU1 48 LVDS I/O 3LU2 48 SDM shared LVDS I/O SDM_U1 29 SDM shared LVDS I/O SDM_U2 29 3V I/O U10 8 3V I/O U12 8 3V I/O U20 8 3V I/O U22 8 i. -

Radiation, Protection of the Public and the Environment (Poster Session 1) Origin and Migration of Cs-137 in Jordanian Soils

Major scientific thematic areas: TA6 – Radiation, Protection of the Public and the Environment (Poster session 1) Origin and Migration of Cs-137 in Jordanian Soils Ahmed Qwasmeh, Helmut W. Fischer IUP- Institute for Environmental Physics, Bremen University, Germany Abstract Whilst some research and publication has been done and published about natural radioactivity in Jordan, only one paper has been published about artificial radioactivity in Jordanian soils (Al Hamarneh 2003). It reveals high concentrations of 137Cs and 90Sr in some regions in the northwest section of Jordan. The origin of this contamination was not determined. Two sets of soil samples were collected and brought from northwest section of Jordan for two reasons, namely; the comparable high concentration of 137Cs in this region according to the above-mentioned paper and because most of the population concentrates in this region. The first set of samples was collected in April 2004 from eleven different sites of this region of Jordan. The second set of samples has been brought in July 2005 from six of the previous sites where we had found higher 137Cs contamination. The second set was collected as thinner sliced soil samples for further studying and to apply a suitable model for 137Cs migration in soil. Activity of 137Cs was measured using a HpGe detector of 50% relative efficiency and having resolution of 2keV at 1.33MeV. Activity of 90Sr was measured for the samples of four sites of the first set of samples, using a gas-filled proportional detector with efficiency of 21.3% cps/Bq. The total inventory of 137Cs in Bq/m2 has been calculated and the correlation between 137Cs inventory and annual rainfall and site Altitude has been studied. -

1St IRF Asia Regional Congress & Exhibition

1st IRF Asia Regional Congress & Exhibition Bali, Indonesia November 17–19 , 2014 For Professionals. By Professionals. "Building the Trans-Asia Highway" Bali’s Mandara toll road Executive Summary International Road Federation Better Roads. Better World. 1 International Road Federation | Washington, D.C. ogether with the Ministry of Public Works Indonesia, we chose the theme “Building the Trans-Asia Highway” to bring new emphasis to a visionary project Tthat traces its roots back to 1959. This Congress brought the region’s stakeholders together to identify new and innovative resources to bridge the current financing gap, while also sharing case studies, best practices and new technologies that can all contribute to making the Trans-Asia Highway a reality. This Congress was a direct result of the IRF’s strategic vision to become the world’s leading industry knowledge platform to help countries everywhere progress towards safer, cleaner, more resilient and better connected transportation systems. The Congress was also a reflection of Indonesia’s rising global stature. Already the largest economy in Southeast Asia, Indonesia aims to be one of world’s leading economies, an achievement that will require the continued development of not just its own transportation network, but also that of its neighbors. Thank you for joining us in Bali for this landmark regional event. H.E. Eng. Abdullah A. Al-Mogbel IRF Chairman Minister of Transport, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Indonesia Hosts the Region’s Premier Transportation Meeting Indonesia was the proud host to the 1st IRF Asia Regional Congress & Exhibition, a regional gathering of more than 700 transportation professionals from 52 countries — including Ministers, senior national and local government officials, academics, civil society organizations and industry leaders. -

Object Recognition and Location Memory in Monkeys with Excitotoxic Lesions of the Amygdala and Hippocampus

The Journal of Neuroscience, August 15, 1998, 18(16):6568–6582 Object Recognition and Location Memory in Monkeys with Excitotoxic Lesions of the Amygdala and Hippocampus Elisabeth A. Murray and Mortimer Mishkin Laboratory of Neuropsychology, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892 Earlier work indicated that combined but not separate removal combined amygdala and hippocampal lesions performed as of the amygdala and hippocampus, together with the cortex well as intact controls at every stage of testing. The same underlying these structures, leads to a severe impairment in monkeys also were unimpaired relative to controls on an anal- visual recognition. More recent work, however, has shown that ogous test of spatial memory, delayed nonmatching-to- removal of the rhinal cortex, a region subjacent to the amygdala location. It is unlikely that unintended sparing of target struc- and rostral hippocampus, yields nearly the same impairment as tures can account for the lack of impairment; there was a the original removal. This raises the possibility that the earlier significant positive correlation between the percentage of dam- results were attributable to combined damage to the rostral and age to the hippocampus and scores on portions of the recog- caudal portions of the rhinal cortex rather than to the combined nition performance test, suggesting that, paradoxically, the amygdala and hippocampal removal. To test this possibility, we greater the hippocampal damage, the better the recognition. trained rhesus monkeys on delayed nonmatching-to-sample, a The results show that, within the medial temporal lobe, the measure of visual recognition, gave them selective lesions of rhinal cortex is both necessary and sufficient for visual the amygdala and hippocampus made with the excitotoxin recognition. -

Road, Transport Sector of Mongolia

ROAD,ROAD, TRANSPORTTRANSPORT SECTORSECTOR OFOF MONGOLIAMONGOLIA Ministry of Road, transport, construction and urban development ContentsContents 1. TransportTransport managementmanagement structurestructure 2. Present Transport network 3. Road 4. Road Transport 5. Railway Transport 6. Civil aviation 7. Water transpor 8. Problem faced in transport sector TransportTransport managementmanagement structurestructure Government Ministry of Road, transport, construction and urban development Civil Aviation Authority Transport Service Center Airlines Road transportation companies Railway Authority Road Research and Supervision Center Railway companies Road construction and maintenance companies Present Transport network Õàíäãàéò Õàíõ Óëààíáàéøèíò Ýðýýíöàâ Àðö ñóóðü Áàãà-¯ åíõ Àëòàíáóëàã ÓËÀÀÍÃÎÌ ÕªÂÑÃªË ªËÃÈÉ ÓÂÑ ÌªÐªÍ ÄÀÐÕÀÍ Äàâàí ÁÀßÍ-ªËÃÈÉ ÑÝËÝÍÃÝ Õàâèðãà ÕÎÂÄ ÇÀÂÕÀÍ ÁÓËÃÀÍ ÝÐÄÝÍÝÒ ÀÐÕÀÍÃÀÉ ÁÓËÃÀÍ ÓËÀÀÍÁÀÀÒÀÐ ÕÝÍÒÈÉ Óëèàñòàé ×ÎÉÁÀËÑÀÍ ÄÎÐÍÎÄ ÇÓÓÍÌÎÄ ÕÎÂÄ ÖÝÖÝÐËÝà Ҫ ªÍĪÐÕÀÀÍ ßðàíò ÀËÒÀÉ ¯ åí÷ ÃÎÂÜѯ ÌÂÝÐ ÁÀÐÓÓÍ-ÓÐÒ ÁÀßÍÕÎÍÃÎÐ ÀÐÂÀÉÕÝÝÐ ×ÎÉРѯ ÕÁÀÀÒÀÐ Áè÷èãò ÃÎÂÜ-ÀËÒÀÉ ÌÀÍÄÀËÃÎÂÜ ªÂªÐÕÀÍÃÀÉ ÄÓÍÄÃÎÂÜ ÑÀÉÍØÀÍÄ Áóðãàñòàé ÁÀßÍÕÎÍÃÎÐ ÄÎÐÍÎÃÎÂÜ Airport with paved Çàìûí-¯ ¿ä running way ÄÀËÀÍÇÀÄÃÀÄ ªÌͪÃÎÂÜ Õàíáîãä Ãàøóóíñóõàéò Paved road Airport with improved running Railway network way Gravel road Airport with earth running way Earth road NumberNumber ofof TransportTransport MeansMeans Sea transport Road transport car, 78750 boat, 23 buses 9692 ship, 6 special 3859 truck other, 5 24620 Air transport Railway transport An, Fokker, Truck 2482 7 -

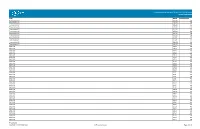

ASEAN Connectivity, Project Information Sheet

ASEAN Connectivity Project Information Sheets one vision one identity one community The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. The ASEAN Secretariat Public Outreach and Civil Society Division 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110, Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 Fax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 E-mail : [email protected] General information on ASEAN appears online at the ASEAN Website: www.asean.org Catalogue-in-Publication Data ASEAN Connectivity Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, August 2012 The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgement. Copyright Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) 2012 All rights reserved PHYSICAL CONNECTIVITY PrOjECT INfOrmATION SHEET mPAC PP/A1/01 CONSTRUCTION OF THE ASEAN HIGHWAY NETWORK (AHN) MISSING LINKS AND UPGRADE OF TRANSIT TRANSPORT ROUTES IN LAO PDR AND MYANMAR PrOjECT DESCrIPTION PrOjECT STATuS ASEAN HIGHWAY Given the growing regional integration and cooperation Seeking technical in ASEAN, the development of high quality transport assistance and funding NETWORK infrastructure is a crucial element to building a competitive ASEAN Community with equitable economic TArgET COmPLETION development. However, ASEAN with total land area DATE of around 4.4 million sq. km faces challenges with poor December 2015 quality of roads and incomplete road networks. The ASEAN Highway Network (AHN) project is a flagship ImPLEmENTINg bODIES infrastructure project that seeks to bring connectivity Ministry of Public across borders and confer many benefits, such as Works and Transport improved competitiveness of regional production of Lao PDR, Ministry networks, better trade and investment flows, and of Construction of reductions in development gaps.