Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute with China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Himalaya Insight Special

HIMALAYA INSIGHT SPECIAL Duration: 08 Nights / 09 Days (Validity: May to September) Destinations Covered: Leh, Monasteries, Sham Valley, Indus Valley, Tsomoriri Lake, Tsokar Lake, Pangong Lake, Turtuk & Nubra Valley The Journey Begins Now! DAY 01: ARRIVE LEH Arrival Leh Kushok Bakula Airport (This must be one of the MOST SENSATIONAL FLIGHTS IN THE WORLD. On a clear day from one side of the aircraft can be seen in the distance the peaks of K2, Nanga Parbat, Gasherbrum and on the other side of the aircraft, so close that you feel you could reach out and touch it, is the Nun Kun massif.) Upon arrival you will met by our representative and transfer to Hotel for Check in. Complete day for rest and leisure to acclimatize followed by Welcome tea or Coffee at the Hotel. Evening Visit to LEH MARKET & SHANTI STUPA. Dinner & Overnight at Hotel. DAY 02: LEH TO SHAM VALLEY (92 KMS / 4 HRS) After breakfast you drive downstream along the River Indus on Leh – Kargil Highway. Enroute visiting GURUDWARA PATTHAR SAHIB Nestled deep in the Himalayas, which was built by the Lamas of Leh in 1517 to commemorate the visit of Guru Nanak Dev. A drive of another 4 km took us to MAGNETIC HILL which defies the law of gravity. It has been noticed that when a vehicle is parked on neutral gear on this metallic road the vehicle slides up & further Driving through a picturesque landscape we reached the CONFLUENCE OF THE INDUS AND ZANSKAR RIVER 4 km before Nimmu village, Just before Saspul a road to the right takes you for your visit to the LIKIR MONASTERY. -

Gandhi Wields the Weapon of Moral Power (Three Case Stories)

Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power (Three Case Stories) By Gene Sharp Foreword by: Dr. Albert Einstein First Published: September 1960 Printed & Published by: Navajivan Publishing House Ahmedabad 380 014 (INDIA) Phone: 079 – 27540635 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.navajivantrust.org Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power FOREWORD By Dr. Albert Einstein This book reports facts and nothing but facts — facts which have all been published before. And yet it is a truly- important work destined to have a great educational effect. It is a history of India's peaceful- struggle for liberation under Gandhi's guidance. All that happened there came about in our time — under our very eyes. What makes the book into a most effective work of art is simply the choice and arrangement of the facts reported. It is the skill pf the born historian, in whose hands the various threads are held together and woven into a pattern from which a complete picture emerges. How is it that a young man is able to create such a mature work? The author gives us the explanation in an introduction: He considers it his bounden duty to serve a cause with all his ower and without flinching from any sacrifice, a cause v aich was clearly embodied in Gandhi's unique personality: to overcome, by means of the awakening of moral forces, the danger of self-destruction by which humanity is threatened through breath-taking technical developments. The threatening downfall is characterized by such terms as "depersonalization" regimentation “total war"; salvation by the words “personal responsibility together with non-violence and service to mankind in the spirit of Gandhi I believe the author to be perfectly right in his claim that each individual must come to a clear decision for himself in this important matter: There is no “middle ground ". -

Framing, Transnational Diffusion, and African- American Intellectuals in the Land of Gandhi

IRSH 49 (2004), Supplement, pp. 19–40 DOI: 10.1017/S0020859004001622 # 2004 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Framing, Transnational Diffusion, and African- American Intellectuals in the Land of Gandhi Sean Chabot Summary: Most of the contentious-politics scholars who pioneered the study of framing in social movements now also recognize the importance of transnational diffusion between protest groups. Interestingly, though, they have not yet specified how these two processes intersect. This article, in contrast, explores the framing- transnational diffusion nexus by highlighting three historical moments of inter- action between African-American intellectuals and Gandhian activists before Martin Luther King, Jr traveled to India in 1959. After briefly reviewing the relevant literature, it illustrates how three different types of ‘‘itinerant’’ African- American intellectuals – mentors like Howard Thurman, advisors like Bayard Rustin, and peers like James Lawson – framed the Gandhian repertoire of nonviolent direct action in ways that made it applicable during the American civil rights movement. The final section considers possible implications for social movement theory and fertile areas for further research. In February 1959, a few years after the Montgomery bus boycott had anointed him as a prophet of nonviolence, Martin Luther King, Jr arrived in India to talk with fellow disciples of Gandhi and witness the effects of the Indian independence movement. He and his wife, Coretta, toured the country, had dinner with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, visited Gandhi’s ashrama (self-sufficient communes), participated in conferences, and attended numerous receptions in their honor. During their four-week stay in India, the Kings discussed Gandhian nonviolent action with native experts like Dr Radhakrishnan, India’s Vice-President; Jayaprakash Narain, a contemporary protest leader; and G. -

Nonviolent Weapons

1 Nonviolent Weapons The Transnationalism of Nonviolent Resistance Liam Comer-Weaver Dept. of International Affairs, University of Colorado April 1, 2015 Thesis Advisor: Dr. Lucy Chester Defense Committee: Dr. Victoria Hunter Dr. Benjamin Teitelbaum 2 Abstract This thesis takes a deep historical look at the adaptation of Mohandas Gandhi’s nonviolent ideology and strategy in the civil rights movement in the AmeriCan South in order to understand the Composition, ConstruCtion, and behavior of the modern nonviolent movement known as 15M in Spain. The Complete translation of Gandhi’s repertoire resulted in the formation of subversive groups, or Contentious Communities, whiCh shared the Common goal of desegregation and Cultural integration of the southern black population. These Contentious Communities regrouped in nonviolent efforts, and interaCted as a groupusCule with the same ideology. This adaptation of nonviolent ideology and strategy also recently occurred in what is known as the 15M movement in Spain. The 15M movement is similarly Composed of many diverse Contentious Communities whose ColleCtive purpose is eConomiC equality and inCreased representation in government. 3 Table of Contents Glossary of Key Terms and Organizations .................................................................................. 4 Preface ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Part I: Nonviolent Resistance Campaigns .................................................................................. -

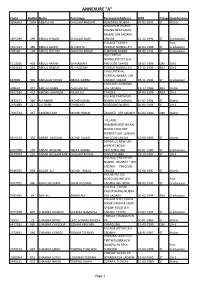

List of Candidates for Physical Efficiency Test for the Post of Wildlife/Forest Guard in Alphabetical

ANNEXURE "A" CanId RollNo Name Parentage PermanentAddress DOB CategoryQualification 9396603 1004 ABBASS ALI GHULAM HASSAN BOGDANG NUBRA 05-02-2001 ST Matric KHALKHAN MANAY- KHANG NEAR JAMA MASJID LEH LADAKH 1855389 499 ABDUL KHALIQ GHULAM NABI 194101 12-12-1994 ST Graduation VILLAGE TYAKSHI Post 1557437 389 ABDUL QADIR ALI MOHD TURTUK NUBRA LEH 30-04-1988 ST Graduation 778160 158 ABDUL QAYUM GHULAM MOHD SUMOOR NUBRA 04-02-1991 ST Graduation R/O TURTUK NURBA,DISTICT LEH, 5113265 402 ABDUL RAHIM GH HASSAN PIN CODE 194401 28-03-1996 OM 10+2 6309413 334 ABDUL RAWUF ALI HUSSAIN TURTUK NUBRA LEH 17-12-1995 RBA 10+2 CHULUNGKHA, TURTUK, NUBRA, LEH 697699 301 ABDULLAH KHAN ABDUL KARIM LADAKH-194401 02-11-1991 ST Graduation CHUCHOT GONGMA 408661 912 ABID HUSSAIN GHULAM ALI LEH LADAKH 19-12-1986 RBA Matric 4917184 412 ABIDAH KHANUM NAJAF ALI TYAKSHI 04-03-1996 RBA 10+2 VILLAGE PARTAPUR 3432671 346 ALI AKBAR MOHD KARIM NUBRA LEH LADAKH 15-07-1994 ST Matric 2535888 217 ALI SHAH GH MOHD BOGDANG NUBRA 05-05-1996 ST 10+2 7345534 337 AMAMULLAH MOHD YAQUB ZANGSTI LEH LADAKH 10-03-1999 OM Matric VILLAGE: RAMBIRPUR(THIKSAY) BLOCK:CHUCHOT DISTRICT:LEH LADAKH 6615129 355 ANSAR HUSSAIN MOHD SAJAD PIN CODE:194101 15-06-1995 ST Matric MOHALLA NEW LEH AIRPORT ROAD 6952008 107 ANSAR HUSSAIN ABDUL KARIM SKALZANGLING 01-01-1989 ST Graduation 4370703 255 ANSAR HUSSAIN MIR GHULAM MOHD DISKET NUBRA 23-10-1997 ST 10+2 VILLAGE: PARTAPUR NUBRA DISTRICT : LEH LADAKH PIN CODE: 9346395 993 ASGAR ALI MOHD ISMAIL 194401 25-06-1997 ST Matric HOUSE NO 102 NORGYASLING LEH Post -

A HISTORY of the AMERICAN LEAGUE for PUERTO RICO INDEPENDENCE, 1944-1950 a Thesis by MANUEL A

TRANSNATIONAL FREEDOM MOVEMENTS: A HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN LEAGUE FOR PUERTO RICO INDEPENDENCE, 1944-1950 A Thesis by MANUEL ANTONIO GRAJALES, II Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University-Commerce in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2015 TRANSNATIONAL FREEDOM MOVEMENTS: A HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN LEAGUE FOR PUERTO RICAN INDEPENDENCE, 1944-1950 A Thesis by MANUEL ANTONIO GRAJALES, II Approved by: Advisor: Jessica Brannon-Wranosky Committee: William F. Kuracina Eugene Mark Moreno Head of Department: Judy A. Ford Dean of the College: Salvatore Attardo Dean of Graduate Studies: Arlene Horne iii Copyright © 2015 Manuel Antonio Grajales II iv ABSTRACT TRANSNATIONAL FREEDOM MOVEMENTS: A HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN LEAGUE FOR PUERTO RICO INDEPENDENCE, 1944-1950 Manuel Grajales, MA Texas A&M University-Commerce, 2015 Advisor: Jessica Brannon-Wranosky, PhD A meeting in 1943 between Puerto Rican nationalist leader Pedro Albizu Campos and a group of U.S. pacifists initiated a relationship built on shared opposition to global imperialism. The association centered on the status of Puerto Rico as a colonial possession of the United States. The nationalists argued that Puerto Rico the island’s definition as a U.S. possession violated their sovereignty and called for aggressive resistance against the United States after attempting to initiate change through the electoral process in 1930. Campos developed his brand of nationalism through collaborations with independence activists from India and Ireland while a student at Harvard. Despite the Puerto Rican nationalists’ rhetorically aggressive stance against U.S. imperialism, conversation occurred with groups of Americans who disapproved of their country’s imperial objective. -

Selection List No.1 of Candidates Who Have Applied for Admission to B.Ed

Selection List No.1 of candidates who have applied for admission to B.Ed. Offered through Directorate of Distance Education session-2020 for Leh Chapter Total Sr. Roll No. Name Parentage Address District Cat. Graduation MM MO out of 90 Masters MM MO out of 10 out of 100 OM TASHI NAWANG R/O DURBUK, 1 20612463 YANGZES GALCHAN NEMGO LEH ST BSC 8 7.5 93.75 NYOMA NIMA PHUNTSOK CHANGTHANG, 2 20613648 PALDEN DORJAY LEH LADAKH LEH RBA BA 500 400 72.00 MASTERS 600 458 7.63 79.63 #A021 SPECIAL DECHEN TSERING HOUSING COLONY 3 20611411 CHOSKIT CHOSDAN DISKET TSAL LEH ST BSCAGRI 1000 784 78.40 NAWANG SONAM KHEMI NUBRA LEH 4 20612077 NAMGYAL DORJEY LADAKH UT LEH ST BA 3600 2786 77.39 NUBRA CHARASA TSERING DEACHEN LEH UT LADAKH 5 20611533 LANZES PALJOR 194401 LEH ST BA 3600 2761 76.69 LAKSAM SAMTAN 6 20611628 DAWA KHENRAP SHANG LEH ST BA 3600 2757 76.58 STANZIN MUTUP ZOTPA SKARA LEH 7 20610026 ANGMO GURMET LADAKH LEH ST BSC 3300 2533 69.08 MASTERS 2400 1722 7.18 76.26 RAGASHA PA RIGZEN SKARMA CHUCHOT YOKMA 8 20612617 ANGMO PHUNTSOG LEH LEH ST BSC 3500 2633 75.23 STANZIN KONCHOK VILLAGE 9 20612598 ANGMO CHOSPHEL SKURBUCHAN LEH ST BSC 10 7.5 75.00 JIGMET PHUNCHOK 10 20612618 LAHZES TUNDUP STOK LEH LEH ST BA 2400 1799 74.96 TSEWANG NAWANG VILLAGE 11 20612596 YOUROL TASHI SKURBUCHAN LEH ST BSC 10 7.4 74.00 SONAM TSERING VILLAGE HANU 12 20610838 ANGCHUK DORJAY YOKMA LEH ST BA 3600 2658 73.83 KONCHOK TSEWANG DURBUK TANGTSE 13 20611554 NAMGAIL CHOSPEL LEH UT LADAKH LEH ST BA 3600 2627 72.97 VILLAGE SUDDIQA BOGDANG BLOCK 14 20612745 BANO MOHD MUSSA NUBRA LEH ST BSC 10 7.2 72.00 PHUTITH SONAM MERAK PANGONG 15 20612066 DOLMA PAMBAR LEH LADAKH LEH ST BTECH 800 576 72.00 Selection List No.1 of candidates who have applied for admission to B.Ed. -

Repor T Resumes

REPOR TRESUMES ED 017 908 48 AL 000 990 CHAPTERS IN INDIAN CIVILIZATION--A HANDBOOK OF READINGS TO ACCOMPANY THE CIVILIZATION OF INDIA SYLLABUS. VOLUME II, BRITISH AND MODERN INDIA. BY- ELDER, JOSEPH W., ED. WISCONSIN UNIV., MADISON, DEPT. OF INDIAN STUDIES REPORT NUMBER BR-6-2512 PUB DATE JUN 67 CONTRACT OEC-3-6-062512-1744 EDRS PRICE MF-$1.25 HC-$12.04 299P. DESCRIPTORS- *INDIANS, *CULTURE, *AREA STUDIES, MASS MEDIA, *LANGUAGE AND AREA CENTERS, LITERATURE, LANGUAGE CLASSIFICATION, INDO EUROPEAN LANGUAGES, DRAMA, MUSIC, SOCIOCULTURAL PATTERNS, INDIA, THIS VOLUME IS THE COMPANION TO "VOLUME II CLASSICAL AND MEDIEVAL INDIA," AND IS DESIGNED TO ACCOMPANY COURSES DEALING WITH INDIA, PARTICULARLY THOSE COURSES USING THE "CIVILIZATION OF INDIA SYLLABUS"(BY THE SAME AUTHOR AND PUBLISHERS, 1965). VOLUME II CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING SELECTIONS--(/) "INDIA AND WESTERN INTELLECTUALS," BY JOSEPH W. ELDER,(2) "DEVELOPMENT AND REACH OF MASS MEDIA," BY K.E. EAPEN, (3) "DANCE, DANCE-DRAMA, AND MUSIC," BY CLIFF R. JONES AND ROBERT E. BROWN,(4) "MODERN INDIAN LITERATURE," BY M.G. KRISHNAMURTHI, (5) "LANGUAGE IDENTITY--AN INTRODUCTION TO INDIA'S LANGUAGE PROBLEMS," BY WILLIAM C. MCCORMACK, (6) "THE STUDY OF CIVILIZATIONS," BY JOSEPH W. ELDER, AND(7) "THE PEOPLES OF INDIA," BY ROBERT J. AND BEATRICE D. MILLER. THESE MATERIALS ARE WRITTEN IN ENGLISH AND ARE PUBLISHED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF INDIAN STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN, MADISON, WISCONSIN 53706. (AMM) 11116ro., F Bk.--. G 2S12 Ye- CHAPTERS IN INDIAN CIVILIZATION JOSEPH W ELDER Editor VOLUME I I BRITISH AND MODERN PERIOD U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

Caste Or Colony? Indianizing Race in the United States∗ Daniel Immerwahr Department of History, University of California, Berkeley

Modern Intellectual History, 4, 2 (2007), pp. 275–301 C 2007 Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S1479244307001205 Printed in the United Kingdom caste or colony? indianizing race in the united states∗ daniel immerwahr Department of History, University of California, Berkeley Since the 1830s thinkers in both the United States and India have sought to establish analogies between their respective countries. Although many have felt the US black experience to have obvious parallels in India, there has been a fundamental disagreement about whether being black is comparable to being colonized or to being untouchable. By examining these two competing visions, this essay introduces new topics to the study of black internationalism, including the caste school of race relations, B. R. Ambedkar’s anti-caste movement, and the changing significance of India for Martin Luther King, Jr. In 1999 UNESCO published a short book, intended for a general audience, comparing the careers of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Mohandas K. Gandhi and noting the obvious parallels in their use of nonviolence. Four years later the Motilal Bhimraj Charity Trust put out a similar book, also comparing black politics to Indian politics, although with one major difference. Instead of casting Gandhi as the Indian analogue to King, as UNESCO had done, it cast B. R. Ambedkar, a leader of untouchables and one of Gandhi’s most formidable opponents.1 The difference is not trivial. Gandhi, the hero of the first book, stands as the implicit villain of the second, for Ambedkar believed that the greatest obstacle to the full flourishing of untouchables was the Mahatma himself. -

Expression of Ladakhi Cultural Regionality: ラダック文化にみる地域

Kanazawa Seiryo University Bulletin of the Humanities Vol.3 No.1, pp.25-38, 2018 Expression of Ladakhi Cultural Regionality: Viewed from Language and Local Rituals Takako YAMADA† Abstract Ladakhi culture cannot be discussed without reference to its relations to Tibet and Tibetan culture. The Ladakh dynasty started its rule by one of the three sons of Skyid lde nyima gon (or Nyima gon), the great-grandson of Lang Darma who was the last emperor of the Old Tibetan Empire, also known as an anti-Buddhist king. Later, various Tibetan Buddhist schools have spread subsequently to Ladakh and converted its residents to Tibetan Buddhism. However, when viewed in terms as its polity as a kingdom, Ladakh has not always maintained friendly relations with Tibet, as exemplified by the war that took place in the 17th century between Ladakh and a joint Tibetan-Mongolian army. Rather, Ladakh has been ruled by an independent polity different from that of Tibet, and has maintained its cultural identity. This paper aims to reveal the regionality of contemporary Ladakhi culture as well as its Pan-Tibetan aspects, dealing with how the cultural identity of the Ladakhi is expressed in terms of language and religion, specifically basing on local ritual tradition as well as activities engaged in by the Students’ Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL) in order to maintain Ladakhi culture and language. Keywords Ladakhi culture, regionality, language, local rituals ラダック文化にみる地域性の表出 ─ 言語とローカルな儀礼実践から ─ 山田 孝子† キーワード ラダック文化,地域性,言語,ローカルな儀礼実践 † [email protected] (Faculty of Humanities, Kanazawa Seiryo University) - 25 - Expression of Ladakhi Cultural Regionality 1. -

From Benaras to Leh - the Trade and Use of Silk-Brocade

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2002 From Benaras to Leh - the trade and use of silk-brocade Monisha Ahmed Oxford University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Ahmed, Monisha, "From Benaras to Leh - the trade and use of silk-brocade" (2002). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 498. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/498 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. From Benaras to Leh - the trade and use of silk-brocade / by Monisha Ahmed ( < A weaver in Benaras sits at his pit loom meticulously creating a textile piece of Mahakala. the god of protection for Buddhists. A lama at the festival ( 'cham) at Hemis monastery performs the religious dance, the Mahakala { image on his apron (pang-kheb} gazing out at the devotees as he pirouettes around the courtyard. The two descriptions given above demonstrate the beginning and end of the journey of silk- brocades from Benaras to Leh. This paper looks at the historical context of the trade in silk- ( brocades from Benaras to Leh, and discusses how this trade first started. It presents how these fabrics are made in Benaras and discusses their various uses in Ladakh. Finally, it examines the contemporary status of the trade and the continued importance of silk-brocades in the lives of Buddhist Ladakhis. -

Ladakh Studies 12

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES LADAKH STUDIES _ 12, Autumn 1999 CONTENTS Page: Editorial 2 News from the Association: From the Hon. Sec. 3 Ninth IALS Colloquium at Leh: A Report Martijn van Beek 4 Biennial Membership Meeting John Bray 7 News from Ladakh: 8 The conflict in Ladakh: May-July 1999 MvB 11 Special Report: A Nunnery and Monastery Are Robbed: Zangskar in the Summer of 1998 Kim Gutschow 14 News from Members 16 Obituary: Michael Aris Kim Gutschow 18 Articles: Day of the Lion: Lamentation Rituals and Shia Identity in Ladakh David Pinault 21 A Self-Reliant Economy: The Role of Trade in Pre-Independence Ladakh Janet Rizvi 31 Dissertation Abstracts 39 Book reviews: Bibliography – Northern Pakistan, by Irmtraud Stellrecht (ed.) John Bray 42 Trekking in Ladakh, by Charlie Loram Martijn van Beek 43 Ladakhi Kitchen, by Gabriele Reifenberg Martin Mills 44 Book announcement 46 Bray’s Bibliography Update no. 9 47 Notes on Contributors 56 Drawings by Niels Krag Production: Repro Afdeling, Faculty of Arts, Aarhus University Layout: MvB Support: Department of Ethnography and Social Anthropology, Aarhus University. 1 EDITORIAL This issue of Ladakh Studies is, I hope you will agree, a substantial one in terms of size and the quality of contributions. Apart from the usual items of Ladakh-related news, there are reports on the recent Ninth Colloquium and the membership meeting of the IALS, two major articles, and a large issue of Bray’s Bibliographic Update. Interspersed are smaller items, including an obituary for Michael Aris by Kim Gutschow. Throughout this issue, you will find some line drawings of characters you may recognize.