Past Forward: Understanding Change in Old Leh Town, Ladakh, North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Himalaya Insight Special

HIMALAYA INSIGHT SPECIAL Duration: 08 Nights / 09 Days (Validity: May to September) Destinations Covered: Leh, Monasteries, Sham Valley, Indus Valley, Tsomoriri Lake, Tsokar Lake, Pangong Lake, Turtuk & Nubra Valley The Journey Begins Now! DAY 01: ARRIVE LEH Arrival Leh Kushok Bakula Airport (This must be one of the MOST SENSATIONAL FLIGHTS IN THE WORLD. On a clear day from one side of the aircraft can be seen in the distance the peaks of K2, Nanga Parbat, Gasherbrum and on the other side of the aircraft, so close that you feel you could reach out and touch it, is the Nun Kun massif.) Upon arrival you will met by our representative and transfer to Hotel for Check in. Complete day for rest and leisure to acclimatize followed by Welcome tea or Coffee at the Hotel. Evening Visit to LEH MARKET & SHANTI STUPA. Dinner & Overnight at Hotel. DAY 02: LEH TO SHAM VALLEY (92 KMS / 4 HRS) After breakfast you drive downstream along the River Indus on Leh – Kargil Highway. Enroute visiting GURUDWARA PATTHAR SAHIB Nestled deep in the Himalayas, which was built by the Lamas of Leh in 1517 to commemorate the visit of Guru Nanak Dev. A drive of another 4 km took us to MAGNETIC HILL which defies the law of gravity. It has been noticed that when a vehicle is parked on neutral gear on this metallic road the vehicle slides up & further Driving through a picturesque landscape we reached the CONFLUENCE OF THE INDUS AND ZANSKAR RIVER 4 km before Nimmu village, Just before Saspul a road to the right takes you for your visit to the LIKIR MONASTERY. -

Monsoon-Influenced Glacier Retreat in the Ladakh Range, Jammu And

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 18, EGU2016-166, 2016 EGU General Assembly 2016 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Monsoon-influenced glacier retreat in the Ladakh Range, Jammu and Kashmir Tom Chudley, Evan Miles, and Ian Willis Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge ([email protected]) While the majority of glaciers in the Himalaya-Karakoram mountain chain are receding in response to climate change, stability and even growth is observed in the Karakoram, where glaciers also exhibit widespread surge- type behaviour. Changes in the accumulation regime driven by mid-latitude westerlies could explain such stability relative to the monsoon-fed glaciers of the Himalaya, but a lack of detailed meteorological records presents a challenge for climatological analyses. We therefore analyse glacier changes for an intermediate zone of the HKH to characterise the transition between the substantial retreat of Himalayan glaciers and the surging stability of Karakoram glaciers. Using Landsat imagery, we assess changes in glacier area and length from 1991-2014 across a ∼140 km section of the Ladakh Range, Jammu and Kashmir. Bordering the surging, stable portion of the Karakoram to the north and the Western Himalaya to the southeast, the Ladakh Range represents an important transitional zone to identify the potential role of climatic forcing in explaining differing glacier behaviour across the region. A total of 878 glaciers are semi-automatically identified in 1991, 2002, and 2014 using NDSI (thresholds chosen between 0.30 and 0.45) before being manually corrected. Ice divides and centrelines are automatically derived using an established routine. Total glacier area for the study region is in line with that Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI) and ∼25% larger than the GLIMS Glacier Database, which is apparently more conservative in assigning ice cover in the accumulation zone. -

Ethnobotany of Ladakh (India) Plants Used in Health Care

T. Ethnobivl, 8(2);185-194 Winter 1988 ETHNOBOTANY OF LADAKH (INDIA) PLANTS USED IN HEALTH CARE G. M. BUTH and IRSHAD A. NAVCHOO Department of Botany University of Kashmir Srinagar 190006 India ABSTRACf.-This paper puts on record the ethnobotanical information of some plants used by inhabitants of Ladakh (India) for medicine, A comparison of the uses of these plants in Ladakh and other parts of India reveal that 21 species have varied uses while 19 species are not reported used. INTRODUCTION Ladakh (elev. 3000-59G(}m), the northernmost part of India is one of the most elevated regions of the world with habitation up to 55(}(}m. The general aspect is of barren topography. The climate is extremely dry with scanty rainfall and very little snowfall (Kachroo et al. 1976). The region is traditionally rich in ethnic folklore and has a distinct culture as yet undisturbed by external influences. The majority of the population is Buddhist and follow their own system of medicine, which has been in vogue for centuries and is extensively practiced. It offers interesting insight into an ancient medical profession. The system of medicine is the"Amchi system" (Tibetan system) and the practi tioner, an"Amchi." The system has something in common with the "Unani" (Greek) and"Ayurvedic" (Indian) system of medicine. Unani is the traditional system which originated in the middle east and was followed and developed in the Muslim world; whereas the Ayurvedic system is that followed by Hindus since Rig vedic times. Both are still practiced in India. Though all the three systems make USe of herbs (fresh and dry), minerals, animal products, etc., the Amchi system, having evolved in its special environment, has its own characteristics. -

Ladakh Studies

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES LADAKH STUDIES _ 19, March 2005 CONTENTS Page: Editorial 2 News from the Association: From the Hon. Sec. 3 Nicky Grist - In Appreciation John Bray 4 Call for Papers: 12th Colloquium at Kargil 9 News from Ladakh, including: Morup Namgyal wins Padmashree Thupstan Chhewang wins Ladakh Lok Sabha seat Composite development planned for Kargil News from Members 37 Articles: The Ambassador-Teacher: Reflections on Kushok Bakula Rinpoche's Importance in the Revival of Buddhism in Mongolia Sue Byrne 38 Watershed Development in Central Zangskar Seb Mankelow 49 Book reviews: A Checklist on Medicinal & Aromatic Plants of Trans-Himalayan Cold Desert (Ladakh & Lahaul-Spiti), by Chaurasia & Gurmet Laurent Pordié 58 The Issa Tale That Will Not Die: Nicholas Notovitch and his Fraudulent Gospel, by H. Louis Fader John Bray 59 Trance, Besessenheit und Amnesie bei den Schamanen der Changpa- Nomaden im Ladakhischen Changthang, by Ina Rösing Patrick Kaplanian 62 Thesis reviews 63 New books 66 Bray’s Bibliography Update no. 14 68 Notes on Contributors 72 Production: Bristol University Print Services. Support: Dept of Anthropology and Ethnography, University of Aarhus. 1 EDITORIAL I should begin by apologizing for the fact that this issue of Ladakh Studies, once again, has been much delayed. In light of this, we have decided to extend current subscriptions. Details are given elsewhere in this issue. Most recently we postponed publication, because we wanted to be able to announce the place and exact dates for the upcoming 12th Colloquium of the IALS. We are very happy and grateful that our members in Kargil will host the colloquium from July 12 through 15, 2005. -

Glacier Characteristics and Retreat Between 1991 and 2014 in the Ladakh Range, Jammu and Kashmir

February 24, 2017 Remote Sensing Letters chudley-ladakh-manuscript To appear in Remote Sensing Letters Vol. 00, No. 00, Month 20XX, 1{17 Glacier characteristics and retreat between 1991 and 2014 in the Ladakh Range, Jammu and Kashmir THOMAS R. CHUDLEYy∗, EVAN S. MILESy and IAN C. WILLISy yScott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (Received 29th November 2016) The Ladakh Range is a liminal zone of meteorological conditions and glacier changes. It lies between the monsoon-forced glacier retreat of the Himalaya and Zanskar ranges to the south and the anomalous stability observed in the Karakoram to the north, driven by mid-latitude westerlies. Given the climatic context of the Ladakh Range, the glaciers in the range might be expected to display intermediate behaviour between these two zones. However, no glacier change data have been compiled for the Ladakh Range itself. Here, we examine 864 glaciers in the central section of the Ladakh range, covering a number of smaller glaciers not included in alternative glacier inventories. Glaciers in the range are small (median 0.25 km2; maximum 6.58 km2) and largely distributed between 5000-6000 m above sea level (a.s.l.). 657 glaciers are available for multitemporal analysis between 1991 to 2014 using data from Landsat multispectral sensors. We find glaciers to have retreated -12.8% between 1991{2014. Glacier changes are consistent with observations in the Western Himalaya (to the south) and in sharp contrast with the Karakoram (to the north) in spite of its proximity to the latter. We suggest this sharp transition must be explained at least in part by non-climatic mechanisms (such as debris covering or hypsometry), or that the climatic factors responsible for the Karakoram behaviour are extremely localised. -

6 Nights & 7 Days Leh – Nubra Valley (Turtuk Village)

Jashn E Navroz | Turtuk, Ladakh | Dates 25March-31March’18 |6 Nights & 7 Days Destinations Leh Covered – Nubra : Leh Valley – Nubra (Turtuk Valley V illage)(Turtuk– Village Pangong ) – Pangong Lake – Leh Lake – Leh Trip starts from : Leh airport Trip starts at: LehTrip airport ends at |: LehTrip airport ends at: Leh airport “As winter gives way to spring, as darkness gives way to light, and as dormant plants burst into blossom, Nowruz is a time of renewal, hope and joy”. Come and experience this festive spirit in lesser explored gem called Turtuk. The visual delights would be aptly complemented by some firsthand experiences of the local lifestyle and traditions like a Traditional Balti meal combined with Polo match. During the festival one get to see the flamboyant and vibrant tribe from Balti region, all dressed in their traditional best. Day 01| Arrive Leh (3505 M/ 11500 ft.) Board a morning flight and reach Leh airport. Our representative will receive you at the terminal and you then drive for about 20 minutes to reach Leh town. Check into your room. It is critical for proper acclimatization that people flying in to Leh don’t indulge in much physical activity for at least the first 24hrs. So the rest of the day is reserved for relaxation and a short acclimatization walk in the vicinity. Meals Included: L & D Day 02| In Leh Post breakfast, visit Shey Monastery & Palace and then the famous Thiksey Monastery. Drive back and before Leh take a detour over the Indus to reach Stok Village. Enjoy a traditional Ladakhi meal in a village home later see Stok Palace & Museum. -

OCTOBER-2019 JNANAGANGOTHRI Monthly Current Affairs 1

OCTOBER-2019 JNANAGANGOTHRI Monthly Current Affairs WWW.IASJNANA.COM 1 OCTOBER-2019 JNANAGANGOTHRI Monthly Current Affairs the JSS Academy of Higher Education and State Research at Varuna village. 1. Mysuru Dasara festival inaugurated in On the third day on October 12, Mr.Kovind Karnataka will visit Swami Vivekananda Yoga The ten-day Mysuru Dasara festival was Anusandhana Sansthana in Bengaluru after a inaugurated by Kannada novelist Dr. S L breakfast meeting with Chief Justice and Bhyrappa by offering floral tributes to the Judges of Karnataka High Court and also idol of Goddess Chamundeshwari atop paying a visit to the house of former Union Chamundi Hill. Chief Minister B S Minister Late H N Ananth Kumar. Yediyurappa and other dignitaries were present on this occasion. 3. Autorickshaw owners in AP to get Rs 10,000 The festival will be marked by cultural as grant programmes, sports events, wrestling The Andhra Pradesh Government launched a competition, film and food festival, book welfare scheme- YSR Vahana Mitra - under exhibition, flower shows. The festivities will which the owner-driver of an auto-rickshaw, or culminate with the grand elephant procession taxicab, gets Rs 10,000 grant per annum. on Vijayadashmi day. More than 1.73 lakh auto owner-drivers would benefit from this scheme and only 2,000 or so applications had been rejected. The The cultural capital of Karnataka and city of Government had allocated Rs 400 crore for it. palaces is decked up for the world-famous Dasara festivities. The illuminated palaces, 4. 63rd Dhammachakra Pravartan Din to be fountains, flower decorations and the display celebrated Nagpur of tradition and heritage are drawing crowds in In Maharashtra, 63rd Dhammachakra large numbers from across the world. -

The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh

The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’ Laurianne Bruneau & John Vincent Bellezza I. An introduction to the rock art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh his paper examines common thematic and esthetic features discernable in the rock art of the western portion of the T Tibetan plateau.1 This rock art is international in scope; it includes Ladakh (La-dwags, under Indian jurisdiction), Tö (Stod) and the Changthang (Byang-thang, under Chinese administration) hereinafter called Upper Tibet. This highland rock art tradition extends between 77° and 88° east longitude, north of the Himalayan range and south of the Kunlun and Karakorum mountains. [Fig.I.1] This work sets out the relationship of this art to other regions of Inner Asia and defines what we call the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’. The primary materials for this paper are petroglyphs (rock carvings) and pictographs (rock paintings). They comprise one of the most prolific archaeological resources on the Western Tibetan Plateau. Although pictographs are quite well distributed in Upper 1 Bellezza would like to heartily thank Joseph Optiker (Burglen), the sole sponsor of the UTRAE I (2010) and 2012 rock art missions, as well as being the principal sponsor of the UTRAE II (2011) expedition. He would also like to thank David Pritzker (Oxford) and Lishu Shengyal Tenzin Gyaltsen (Gyalrong Trokyab Tshoteng Gön) for their generous help in completing the UTRAE II. Sponsors of earlier Bellezza expeditions to survey rock art in Upper Tibet include the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation (New York) and the Asian Cultural Council (New York). -

India's Best Kept Secret

Veronica Reilly India’s Best Kept Secret We are hurtling along the Highest Motorable Road in the World in a beat-up Jeep. The young Ladakhi driver, who seemed so kind and friendly back in the capital city, Leh, is clearly mad. He swings around blind hairpin turns on this single lane road carved out of a mountainside without the customary horn blaring. The almost continuous use of the horn is the way that people drive on these one-lane mountain roads in the high Himalaya without having frequent head-on collisions. Our driver likes the aspect of Himalayan driving custom that requires hurtling along at preposterous speeds, but does not accompany this reckless behavior with any- where near the requisite amount of horn usage. Himank, the road’s authority here, has even painted large signs black let- ters against a yellow background, on the bare rock walls above us that read, “Horn please.” Immediately to my left and thousands of feet below lies the rocky brown bottom of a ravine. There are only intermittent guardrails. I try to imagine that the window overlooking the precipice is actually a television screen. I breathe deeply and try to let go of my attachment to life. We are among Buddhists, after all. Perhaps our driver gains his cavalier attitude from a firm belief in reincarnation, a belief that I don’t share, although I am suddenly reevaluating the possibility. The beginning of the trip, several hours ago, was joc- ular, and the five of us, thrown together for just a few days, introduced ourselves. -

Economic Review” of District Leh, for the Year 2014-15

PREFACE The District Statistics and Evaluation Agency Leh under the patronage of Directorate of Economic and Statistics (Planning and Development Department) is bringing out annual publication titled “Economic Review” of District Leh, for the year 2014-15. The publication 22st in the series, presents the progress achieved in various socio-economic facts of the district economy. I hope that the publication will be a useful tool in the hands of planners, administrators, Policy makers, academicians and other users and will go a long way in helping them in their respective pursuit. Suggestions to improve the publication in terms of coverage, quality etc. in the future issue of the publication will be appreciated Tashi Tundup District statistics and Evaluation Officer Leh CONTENTS Page No. District Profile 1-6 Agriculture and Allied Activities • Agriculture 7-9 • Horticulture 10 • Animal Husbandry 11-13 • Sheep Husbandry 14-15 • Forest 16 • Soil Conservation 17 • Cooperative 17-18 • Irrigation 19 Industries and Employment • Industries 19-20 • Employment & Counseling Centre 20 • Handicraft/Handloom 21 Economic Infrastructure • Power 21-22 • Tourism 22-23 • Financial institution 24-25 • Transport and communication 24-27 • Information Technology 27-28 Social Sector • Housing 29 • Education 29-31 • Health 31-33 • Water Supply and Rural Sanitation 33 • Women and Child Development 34-36 1 DISTRICT PROFILE . Although, Leh district is one of the largest districts of the country in terms of area, it has the lowest population density across the entire country. The district borders Pakistan occupied Kashmir and Chinese occupied Ladakh in the North and Northwest respectively, Tibet in the east and Lahoul-Spiti area of Himachal Pradesh in the South. -

THE EARLY BUDDHIST HERITAGE of LADAKH RECONSIDERED CHRISTIAN LUCZANITS Much Ofwhat Is Generally Considered to Represent the Earl

THE EARLY BUDDHIST HERITAGE OF LADAKH RECONSIDERED CHRISTIAN LUCZANITS Much ofwhat is generally considered to represent the earliest heritage of Ladakh cannot be securely dated. It even cannot be said with certainty when Buddhism reached Ladakh. Similarly, much ofwhat is recorded in inscriptions and texts concerning the period preceding the establishment of the Ladakhi kingdom in the late 151h century is either fragmentary or legendary. Thus, only a comparative study of these records together 'with the architectural and artistic heritage can provide more secure glimpses into the early history of Buddhism in Ladakh. This study outlines the most crucial historical issues and questions from the point of view of an art historian and archaeologist, drawing on a selection of exemplary monuments and o~jects, the historical value of which has in many instances yet to be exploited. vVithout aiming to be so comprehensive, the article updates the ground breaking work of A.H. Francke (particularly 1914, 1926) and Snellgrove & Skorupski (1977, 1980) regarding the early Buddhist cultural heritage of the central region of Ladakh on the basis that the Alchi group of monuments l has to be attributed to the late 12 and early 13 th centuries AD rather than the 11 th or 12 th centuries as previously assumed (Goepper 1990). It also collects support for the new attribution published by different authors since Goepper's primary article. The nmv fairly secure attribution of the Alchi group of monuments shifts the dates by only one century} but has wide repercussions on I This term refers to the early monuments of Alchi, rvIangyu and Sumda, which are located in a narrow geographic area, have a common social, cultural and artistic background, and may be attIibuted to within a relatively narrow timeframe. -

List of Candidates for Physical Efficiency Test for the Post of Wildlife/Forest Guard in Alphabetical

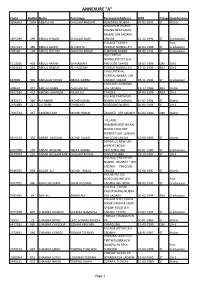

ANNEXURE "A" CanId RollNo Name Parentage PermanentAddress DOB CategoryQualification 9396603 1004 ABBASS ALI GHULAM HASSAN BOGDANG NUBRA 05-02-2001 ST Matric KHALKHAN MANAY- KHANG NEAR JAMA MASJID LEH LADAKH 1855389 499 ABDUL KHALIQ GHULAM NABI 194101 12-12-1994 ST Graduation VILLAGE TYAKSHI Post 1557437 389 ABDUL QADIR ALI MOHD TURTUK NUBRA LEH 30-04-1988 ST Graduation 778160 158 ABDUL QAYUM GHULAM MOHD SUMOOR NUBRA 04-02-1991 ST Graduation R/O TURTUK NURBA,DISTICT LEH, 5113265 402 ABDUL RAHIM GH HASSAN PIN CODE 194401 28-03-1996 OM 10+2 6309413 334 ABDUL RAWUF ALI HUSSAIN TURTUK NUBRA LEH 17-12-1995 RBA 10+2 CHULUNGKHA, TURTUK, NUBRA, LEH 697699 301 ABDULLAH KHAN ABDUL KARIM LADAKH-194401 02-11-1991 ST Graduation CHUCHOT GONGMA 408661 912 ABID HUSSAIN GHULAM ALI LEH LADAKH 19-12-1986 RBA Matric 4917184 412 ABIDAH KHANUM NAJAF ALI TYAKSHI 04-03-1996 RBA 10+2 VILLAGE PARTAPUR 3432671 346 ALI AKBAR MOHD KARIM NUBRA LEH LADAKH 15-07-1994 ST Matric 2535888 217 ALI SHAH GH MOHD BOGDANG NUBRA 05-05-1996 ST 10+2 7345534 337 AMAMULLAH MOHD YAQUB ZANGSTI LEH LADAKH 10-03-1999 OM Matric VILLAGE: RAMBIRPUR(THIKSAY) BLOCK:CHUCHOT DISTRICT:LEH LADAKH 6615129 355 ANSAR HUSSAIN MOHD SAJAD PIN CODE:194101 15-06-1995 ST Matric MOHALLA NEW LEH AIRPORT ROAD 6952008 107 ANSAR HUSSAIN ABDUL KARIM SKALZANGLING 01-01-1989 ST Graduation 4370703 255 ANSAR HUSSAIN MIR GHULAM MOHD DISKET NUBRA 23-10-1997 ST 10+2 VILLAGE: PARTAPUR NUBRA DISTRICT : LEH LADAKH PIN CODE: 9346395 993 ASGAR ALI MOHD ISMAIL 194401 25-06-1997 ST Matric HOUSE NO 102 NORGYASLING LEH Post