India's Best Kept Secret

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Review” of District Leh, for the Year 2014-15

PREFACE The District Statistics and Evaluation Agency Leh under the patronage of Directorate of Economic and Statistics (Planning and Development Department) is bringing out annual publication titled “Economic Review” of District Leh, for the year 2014-15. The publication 22st in the series, presents the progress achieved in various socio-economic facts of the district economy. I hope that the publication will be a useful tool in the hands of planners, administrators, Policy makers, academicians and other users and will go a long way in helping them in their respective pursuit. Suggestions to improve the publication in terms of coverage, quality etc. in the future issue of the publication will be appreciated Tashi Tundup District statistics and Evaluation Officer Leh CONTENTS Page No. District Profile 1-6 Agriculture and Allied Activities • Agriculture 7-9 • Horticulture 10 • Animal Husbandry 11-13 • Sheep Husbandry 14-15 • Forest 16 • Soil Conservation 17 • Cooperative 17-18 • Irrigation 19 Industries and Employment • Industries 19-20 • Employment & Counseling Centre 20 • Handicraft/Handloom 21 Economic Infrastructure • Power 21-22 • Tourism 22-23 • Financial institution 24-25 • Transport and communication 24-27 • Information Technology 27-28 Social Sector • Housing 29 • Education 29-31 • Health 31-33 • Water Supply and Rural Sanitation 33 • Women and Child Development 34-36 1 DISTRICT PROFILE . Although, Leh district is one of the largest districts of the country in terms of area, it has the lowest population density across the entire country. The district borders Pakistan occupied Kashmir and Chinese occupied Ladakh in the North and Northwest respectively, Tibet in the east and Lahoul-Spiti area of Himachal Pradesh in the South. -

Ladakh Subsate BSAP

DRAFT BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY & ACTION PLAN: SUB –STATE LADAKH 8. STRATEGY & ACTION PLAN The Action Plan below spells out detailed sets of action, jointly elaborated by the main stakeholders, which are meant to translate the strategies presented in the previous chapter into actual biodiversity protection on the ground. The underlying approach has been to design actions that are SMART, in other words Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Time Bound. No systematic attempt has been made to define priorities between actions, locations and actors. However the sequence of actions as they are presented under the different strategies is broadly indicative of priorities agreed by the participants in the BSAP process. I. STRATEGIES & ACTIONS FOR CONSERVATION OF WILD FLORA AND HABITATS DIVERSITY Strategy: Ensure conservation and sustainable management of natural forests and indigenous tree & shrub species Actions By whom Where When Finance Complete inventory & conduct thorough ecological re- Forest Department, SKUAST Whole of La- Starting No addi- search on distribution/status/conservation/propagation of FRL, WII dakh (Leh & from spring/ tional funds indigenous trees & shrubs focusing on rare & threatened Kargil District) mid-2003 required species like Juniper, Birch etc. (see Appendixes 2 & 3) Identify key areas of natural wood/shrubland & incorporate LAHDC/Forest, Wildlife Deptt/ -do- By 2003 -do- them in Protected Areas & Community Conserved Areas SKUAST/WII/loc. communities 1. Identify, list & map natural forests areas & transmit the Forest Department -do- First half of -do- information to LAHDC and other key stake holders (Wild- 2003 life Deptt, PWD, Armed Forces, loc. com. representatives) 2. Investigate legal status of selected forest areas LAHDC/Forest, Revenue Deptt. -

03 Economic Review 2015-16

0 1 DISTRICT PROFILE Although, Leh district is one of the largest districts of the country in terms of area, it has the lowest population density across the entire country. The district borders Pakistan occupied Kashmir and Chinese occupied Ladakh in the North and Northwest respectively, Tibet in the east and Lahoul-Spiti area of Himachal Pradesh in the South. The district of Leh forms the Northern tip of the Indian Sub Continent. According to the Geographical experts, the district has several other features, which make it unique when compared with other parts of the Indian sub-continent. The district is the coldest and most elevated inhabited region in the country with altitude ranging from 2300 meters to 5000 meters. As a result of its high altitude locations, annual rainfall is extremely low. This low status of precipitation has resulted in scanty vegetation, low organic content in the soil and loose structure in the cold desert. But large-scale plantation has been going in the district since 1955 and this state of affairs is likely to change. The ancient inhabitants of Ladakh were Dards, an Indo- Aryan race. Immigrants of Tibet, Skardo and nearby parts like Purang, Guge settled in Ladakh, whose racial characters and cultures were in consonance with early settlers. Buddhism traveled from central India to Tibet via Ladakh leaving its imprint in Ladakh. Islamic missionaries also made a peaceful penetration of Islam in the early 16 th century. German Moravian Missionaries having cognizance of East India Company also made inroads towards conversion but with little success. In the 10 th century AD, Skit Lde Nemagon, the ruler of Tibet, invaded Ladakh where there was no central authority. -

Himank/14/2020-21 Notice Inviting Tenders (National Competitive Biddings) Border Roads Organisation Chief Engineer Project Himank

CA NO. : CE (P) HIMANK/ /2020-21 SERIAL PAGE NO: TENDER NO : CE (P) HIMANK/14/2020-21 NOTICE INVITING TENDERS (NATIONAL COMPETITIVE BIDDINGS) BORDER ROADS ORGANISATION CHIEF ENGINEER PROJECT HIMANK 1. Online bids are invited on single stage two bid system for” CONSULTANCY FOR DESIGN AND DRAWING(ARCHITECTURAL & STRUCTURAL) AND FOR OBTAINING APPROVAL FROM VARIOUS AUTHORITIES LIKE MUNICIPAL CORPORATION, AIR FORCE ETC FOR CONSTRUCTION OF MULTI-STOREY BUILDING WITH MI ROOM IN N-AREA (PRESENT LOCATION OF HAD) FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF AIR DISPATCH UNIT FOR PROJECT HIMANK AND VIJAYAK AT CHANDIGARH”. The title of above heading on CPPP site https://eprocure.gov.in/eprocure/app “CONSULTANCY FOR DESIGN AND DRAWING(ARCHITECTURAL & STRUCTURAL) AND FOR OBTAINING APPROVAL FROM VARIOUS AUTHORITIES LIKE MUNICIPAL CORPORATION, AIR FORCE ETC FOR CONSTRUCTION OF MULTI-STOREY BUILDING WITH MI ROOM IN N-AREA (PRESENT LOCATION OF HAD) FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF AIR DISPATCH UNIT FOR PROJECT HIMANK AND VIJAYAK AT CHANDIGARH” 2. Tender documents may be downloaded from BRO website www.bro.gov.in (for reference only) and CPPP site https://eprocure.gov.in/eprocure/app as per the schedule as given in CRITICAL DATE SHEET as under:- CRITICAL DATE SHEET Publishing Date 09 Apr 2020 (1100 Hrs) Document Download/Sale Start /Date 09 Apr 2020 (1130 Hrs) Clarification Start Date 10 Apr 2020 (1100 Hrs) Clarification end date 17 Apr 2020 (1100 Hrs) Bid Submission Start Date 18 Apr 2020 (1100 Hrs) Bid Documents Download/Sale End Date 30 Apr 2020 (1100 Hrs) Bid submission end date 30 Apr 2020 (1100 Hrs) Technical Bid Opening Date 01 May 2020 (1100 Hrs) Financial Bid Opening Date Will be informed later 3. -

Page10 Sports.Qxd (Page 1)

FRIDAY, AUGUST 30, 2019 (PAGE 10) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU PM launches 'Fit India Movement', says it's zero Deepa Malik basks in Khel Ratna per cent investment with 100 per cent returns glory, Bajrang misses ceremony NEW DELHI, Aug 29: fixed with change in lifestyle. NEW DELHI, Aug 29: gold-winner heptathlete Swapna Anjum Moudgil, all of who were Bhaskaran (bodybuilding), Ajay "Fitness is the need of the Barman, footballer Gurpreet picked for the Arjuna award this Thakur (kabaddi), Anjum "Fitness is zero per cent hour. But with technology, Paralympic silver-medallist investment with infinite returns", Singh Sandhu, two-time world year. Moudgil (shooting), B Sai physical activity has reduced and Deepa Malik on Thursday said Prime Minister Narendra silver-medallist boxer Sonia Sports Minister Kiren Rijiju, Praneeth (badminton), Tajinder now we have come to a stage became the first Indian woman Modi today while launching a where we count our steps on a Lather, Asian Games silver- HRD Minister Ramesh Pal Singh Toor (athletics), nationwide 'Fit India' Movement' para-athlete and the oldest Pokhriyal, Sports Pramod Bhagat (para sports- mobile app," he said. to be conferred the Rajiv which he believes will take the "It has become fashionable to Seceretary Radhey badminton), Harmeet Rajul country towards a healthier Gandhi Khel Ratna award Shyam Julaniya, Sports Desai (table tennis), Pooja talk about fitness rather act on it. but training commitments future. For few, talking about it is a Authority of India Dhanda (wrestling), Fouaad At a colourful ceremony, kept co-awardee Bajrang Director General Mirza (equestrian), Simran fashion statement which doesn't Punia away from the cere- which included a presentation of help," said the Prime Minister. -

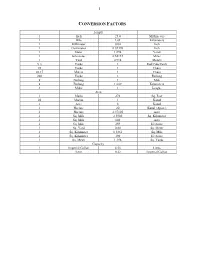

1 Conversion Factors

1 CONVERSION FACTORS Length 1 Inch 25.4 Millimeters 1 Mile 1.61 Kilometers 1 Millimeter 0.04 Inch 1 Centimeter 0.39370 Inch 1 Meter 1.094 Yards 1 Kilometer 0.62137 Miles 1 Yard 0.914 Meters 5 ½ Yards 1 Rod/Pole/Perch 22 Yards 1 Chain 20.17 Maters 1 Chain 220 Yards 1 Furlong 8 Furlong 1 Mile 8 Furlong 1.609 Kilometers 3 Miles 1 League Area 1 Marla 272 Sq. Feet 20 Marlas 1 Kanal 1 Acre 8 Kanal 1 Hectare 20 Kanal (Apox.) 1 Hectare 2.47105 Acre 1 Sq. Mile 2.5900 Sq. Kilometer 1 Sq. Mile 640 Acre 1 Sq. Mile 259 Hectares 1 Sq. Yard 0.84 Sq. Meter 1 Sq. Kilometer 0.3861 Sq. Mile 1 Sq. Kilometer 100 Hectares 1 Sq. Meter 1.196 Sq. Yards Capacity 1 Imperial Gallon 4.55 Litres 1 Litre 0.22 Imperial Gallon 2 Weight 1 Ounce (Oz) 28.3495 Grams 1 Pound 0.45359 Kilogram 1 Long Ton 1.01605 Metric Tone 1 Short Ton 0.907185 Metric Tone 1 Long Ton 2240 Pounds 1 Short Ton 2000 Pounds 1 Maund 82.2857 Pounds 1 Maund 0.037324 Metric Tone 1 Maund 0.3732 Quintal 1 Kilogram 2.204623 Pounds 1 Gram 0.0352740 Ounce 1 Gram 0.09 Tolas 1 Tola 11.664 Gram 1 Ton 1.06046 Metric Tone 1 Tonne 10.01605 Quintals 1 Meteric Tonne 0.984207 Tons 1 Metric Tonne 10 Quintals 1 Metric Ton 1000 Kilogram 1 Metric Ton 2204.63 Pounds 1 Metric Ton 26.792 Maunds (standard) 1 Hundredweight 0.508023 Quintals 1 Seer 0.933 Kiloram 1 Bale of Cotton (392 lbs.) 0.17781 Metric Tonne 1 Metric Tonne 5.6624 Bale of Cotton (392 lbs.) 1 Metric Tonne 5.5116 Bale of Jute (400 lbs.) 1 Quintals 100 Kilogram 1 Bale of jute (400 lbs.) 0.181436 Metric Volume 1 Cubic Yard 0.7646 Cubic Meter 1 Cubic Meter 1.3079 Cubic Yards 1 Cubic Meter 35.3147 Cubic Feet 1 Cubic Foot 0.028 Cubic Meter Temperature C/5 = (F-32) /9 3 District Leh at a Glance Sr. -

Registration No

List of Socities registered with Registrar of Societies of Kashmir S.No Name of the society with address. Registration No. Year of Reg. ` 1. Tagore Memorial Library and reading Room, 1 1943 Pahalgam 2. Oriented Educational Society of Kashmir 2 1944 3. Bait-ul Masih Magarmal Bagh, Srinagar. 3 1944 4. The Managing Committee khalsa High School, 6 1945 Srinagar 5. Sri Sanatam Dharam Shital Nath Ashram Sabha , 7 1945 Srinagar. 6. The central Market State Holders Association 9 1945 Srinagar 7. Jagat Guru Sri Chand Mission Srinagar 10 1945 8. Devasthan Sabha Phalgam 11 1945 9. Kashmir Seva Sadan Society , Srinagar 12 1945 10. The Spiritual Assembly of the Bhair of Srinagar. 13 1946 11. Jammu and Kashmir State Guru Kula Trust and 14 1946 Managing Society Srinagar 12. The Jammu and Kashmir Transport union 17 1946 Srinagar, 13. Kashmir Olympic Association Srinagar 18 1950 14. The Radio Engineers Association Srinagar 19 1950 15. Paritsarthan Prabandhak Vibbag Samaj Sudir 20 1952 samiti Srinagar 16. Prem Sangeet Niketan, Srinagar 22 1955 17. Society for the Welfare of Women and Children 26 1956 Kana Kadal Sgr. 1 18. J&K Small Scale Industries Association sgr. 27 1956 19. Abhedananda Home Srinagar 28 1956 20. Pulaskar Sangeet Sadan Karam Nagar Srinagar 30 1957 21. Sangit Mahavidyalaya Wazir Bagh Srinagar 32 1957 22. Rattan Rani Hospital Sriangar. 34 1957 23. Anjuman Sharai Shiyan J&K Shariyatbad 35 1958 Budgam. 24. Idara Taraki Talim Itfal Shiya Srinagar 36 1958 25. The Tuberculosis association of J&K State 37 1958 Srinagar 26. Jamiat Ahli Hadis J&K Srinagar. -

ORF Occasional Paper#42

EARCH S F E O R U R N E D V A R T E I O S N B ORF OCCASIONAL PAPER #42 O MAY 2013 Sino-Indian Border Infrastructure: An Update Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan Rahul Prakash OBSERVER RESEARCH FOUNDATION Sino-Indian Border Infrastructure: An Update Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan Rahul Prakash OBSERVER RESEARCH FOUNDATION About the Authors Dr. Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan is Senior Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF), New Delhi. Dr. Rajagopalan joined ORF after an almost five-year stint at the National Security Council Secretariat (2003-2007), where she was an Assistant Director. Prior to joining the NSCS, she was Research Officer at the Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. She was also a Visiting Professor at the Graduate Institute of International Politics, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan in early 2012. She is the author of three books: Clashing Titans: Military Strategy and Insecurity Among Asian Great Powers; The Dragon's Fire: Chinese Military Strategy and Its Implications for Asia; and Uncertain Eagle: US Military Strategy in Asia. Rahul Prakash is a Junior Fellow at Observer Research Foundation. His research interests include technology and security, Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) issues and security developments in Asia. He has co-authored a report on Chemical, Biological and Radiological Materials: An Analysis of Security Risks and Terrorist Threats in India, an outcome of a joint study conducted by ORF and the London-based Royal United Services Institute. He has also published Issue Briefs on China’s Progress in Space and Rise of Micro Blogs in China. -

INDO-PACIFIC India's Push for Border Roads

INDO-PACIFIC India’s Push for Border Roads OE Watch Commentary: The government of India has widely discussed plans to purchase new weapons and equipment in response to the dispute with China over the Line of Actual Control (LAC), which intensified in May of this year (see: “The Indian Army’s Shopping List,” OE Watch, September 2020). The accompanying excerpted article reports on another aspect of the Indian government’s plans to deal with the situation on the LAC and it shows how infrastructure will play a role in any future response to incidents amid reports that a few weapons acquisitions have fallen through or have been delayed. The article comes from The Print, an English- language news website in India, and it reports on how the Indian government “is planning to expand the motorable network along the India- China border by building two news roads — one connecting Pooh in Himachal Pradesh Road sign from BRO’s Himank project in Ladakh, India. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sign_in_Ladakh_02.jpg to Chumar in Ladakh, and the other linking Attribution: CC BY YA 4.0 Harsil in Uttarakhand to Karcham in Himachal Pradesh” and that in addition to these roads, the government “stepped up work on an alternate road being built to Daulat Beg Oldie (DBO), where India’s highest airstrip is located, in eastern Ladakh.” The article goes on to note how “the two new roads are not part of the 73 India-China Border Roads (ICBRs) planned for brisk movement of troops and weapons — a project already under way.” The article provides a brief -

Ladakh Studies 12

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES LADAKH STUDIES _ 12, Autumn 1999 CONTENTS Page: Editorial 2 News from the Association: From the Hon. Sec. 3 Ninth IALS Colloquium at Leh: A Report Martijn van Beek 4 Biennial Membership Meeting John Bray 7 News from Ladakh: 8 The conflict in Ladakh: May-July 1999 MvB 11 Special Report: A Nunnery and Monastery Are Robbed: Zangskar in the Summer of 1998 Kim Gutschow 14 News from Members 16 Obituary: Michael Aris Kim Gutschow 18 Articles: Day of the Lion: Lamentation Rituals and Shia Identity in Ladakh David Pinault 21 A Self-Reliant Economy: The Role of Trade in Pre-Independence Ladakh Janet Rizvi 31 Dissertation Abstracts 39 Book reviews: Bibliography – Northern Pakistan, by Irmtraud Stellrecht (ed.) John Bray 42 Trekking in Ladakh, by Charlie Loram Martijn van Beek 43 Ladakhi Kitchen, by Gabriele Reifenberg Martin Mills 44 Book announcement 46 Bray’s Bibliography Update no. 9 47 Notes on Contributors 56 Drawings by Niels Krag Production: Repro Afdeling, Faculty of Arts, Aarhus University Layout: MvB Support: Department of Ethnography and Social Anthropology, Aarhus University. 1 EDITORIAL This issue of Ladakh Studies is, I hope you will agree, a substantial one in terms of size and the quality of contributions. Apart from the usual items of Ladakh-related news, there are reports on the recent Ninth Colloquium and the membership meeting of the IALS, two major articles, and a large issue of Bray’s Bibliographic Update. Interspersed are smaller items, including an obituary for Michael Aris by Kim Gutschow. Throughout this issue, you will find some line drawings of characters you may recognize. -

UPSC Daily Current Affairs 06 AUG 2021

1 UPSC Daily Current Affairs 06 AUG 2021 Umlingla Pass (Topic- GS Paper I –Geography, Source-The Hindu) Why in the news? • The Border Roads Organisation has recently constructed the world highest motorable road in India which passes through Umlingla Pass in Eastern Ladakh. More in news • It is a black-topped, 52-kilometre road that connects many important towns in the Chumar sector of Eastern Ladakh. • This road was constructed under Project Himank. About Umling La Pass • It is located at an altitude of 19,300ft in the union territory of Ladakh. • It stretched to a distance of almost 86km connects Chisumle and Demchok villages. • Both these villages lie close to the Indo-China border in the eastern sector. Significance • The important towns in eastern Ladakh’s Chumar sector will all be connected by this road, which comes as a boon for the local population. • The road provides the residents with an alternative direct route to Demchok and Chisumle from Leh. 2 • It will also increase the region’s socio-economic condition as well as promote tourism in Ladakh. • The road is at a very strategic point as the villages that will be connected by the road are very close to the India-China border in the eastern sector. Related Information About Project Himank • It is a project of the Border Roads Organisation (BRO) in the Ladakh region of northernmost India that started in August 1985. • Under the Himank project, BRO is responsible for the construction and maintenance of roads and related infrastructure in Ladakh along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), including some of the world's highest motorable roads across the Khardung La, Tanglang La and Chang La passes. -

LM Guide.Indd

LADAKH MARATHON Sunday 9th September 2018 RUNNERS INFORMATION GUIDE CONTENTS About Khardungla Challenge Altitude and Acclimatisation Runners’ CONTENT Checklist Route About and Ladakh Cut-Off Marathon time Protected Acclimatisation Area Permit Runners’ Checklist Medical BIB Collection check-up & Timing BIB Race collection Day & Timing Baggage Deposit Getting Medical to Support the start & Hydration point Points Baggage Getting todrop the start point Aid R Stationsace Information 7K - Ladakh Run for Fun Finish 21K- Half line Marathon and Certification 42K- Marathon Finish line and Certification About Ladakh Marathon Ladakh Marathon is a unique opportunity for runners from around India and the world torun with local Ladakhis through an ancient Buddhist kingdom grappling with the rapid changes of today. The historic capital of Leh, the stunning vistas as you cross the Indus River and the dramatic climb up to the Khardung La from Nubra will leave you with lifelong memories and a chance to say you ran Ladakh, the world’s highest marathon. It is an annual event that takes place in LEH during the month of September. Being certified by AIMS (Association of International Marathons and Distance Races), it has put the event on the global marathon calendar. Khardung La Challenge, one of the four races of the event, is now the world’s highest and among the toughest ultra marathons, that is attracting some of the best runners from across the globe. Acclimatisation Acclimatisation is imperative and important if you are planning to participate and run the Ladakh Marathon. It depends entirely on one’s personal body condition as some acclimatise very fast and some take several days.