The Quad Plus Book 09-01-2015.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission and Revolution in Central Asia

Mission and Revolution in Central Asia The MCCS Mission Work in Eastern Turkestan 1892-1938 by John Hultvall A translation by Birgitta Åhman into English of the original book, Mission och revolution i Centralasien, published by Gummessons, Stockholm, 1981, in the series STUDIA MISSIONALIA UPSALIENSIA XXXV. TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by Ambassador Gunnar Jarring Preface by the author I. Eastern Turkestan – An Isolated Country and Yet a Meeting Place 1. A Geographical Survey 2. Different Ethnic Groups 3. Scenes from Everyday Life 4. A Brief Historical Survey 5. Religious Concepts among the Chinese Rulers 6. The Religion of the Masses 7. Eastern Turkestan Church History II. Exploring the Mission Field 1892 -1900. From N. F. Höijer to the Boxer Uprising 1. An Un-known Mission Field 2. Pioneers 3. Diffident Missionary Endeavours 4. Sven Hedin – a Critic and a Friend 5. Real Adversities III. The Foundation 1901 – 1912. From the Boxer Uprising to the Birth of the Republic. 1. New Missionaries Keep Coming to the Field in a Constant Stream 2. Mission Medical Care is Organized 3. The Chinese Branch of the Mission Develops 4. The Bible Dispute 5. Starting Children’s Homes 6. The Republican Frenzy Reaches Kashgar 7. The Results of the Founding Years IV. Stabilization 1912 – 1923. From Sjöholm’s Inspection Tour to the First Persecution. 1. The Inspection of 1913 2. The Eastern Turkestan Conference 3. The Schools – an Attempt to Reach Young People 4. The Literary Work Transgressing all Frontiers 5. The Church is Taking Roots 6. The First World War – Seen from a Distance 7. -

Himalaya Insight Special

HIMALAYA INSIGHT SPECIAL Duration: 08 Nights / 09 Days (Validity: May to September) Destinations Covered: Leh, Monasteries, Sham Valley, Indus Valley, Tsomoriri Lake, Tsokar Lake, Pangong Lake, Turtuk & Nubra Valley The Journey Begins Now! DAY 01: ARRIVE LEH Arrival Leh Kushok Bakula Airport (This must be one of the MOST SENSATIONAL FLIGHTS IN THE WORLD. On a clear day from one side of the aircraft can be seen in the distance the peaks of K2, Nanga Parbat, Gasherbrum and on the other side of the aircraft, so close that you feel you could reach out and touch it, is the Nun Kun massif.) Upon arrival you will met by our representative and transfer to Hotel for Check in. Complete day for rest and leisure to acclimatize followed by Welcome tea or Coffee at the Hotel. Evening Visit to LEH MARKET & SHANTI STUPA. Dinner & Overnight at Hotel. DAY 02: LEH TO SHAM VALLEY (92 KMS / 4 HRS) After breakfast you drive downstream along the River Indus on Leh – Kargil Highway. Enroute visiting GURUDWARA PATTHAR SAHIB Nestled deep in the Himalayas, which was built by the Lamas of Leh in 1517 to commemorate the visit of Guru Nanak Dev. A drive of another 4 km took us to MAGNETIC HILL which defies the law of gravity. It has been noticed that when a vehicle is parked on neutral gear on this metallic road the vehicle slides up & further Driving through a picturesque landscape we reached the CONFLUENCE OF THE INDUS AND ZANSKAR RIVER 4 km before Nimmu village, Just before Saspul a road to the right takes you for your visit to the LIKIR MONASTERY. -

Flagship Species of the Pamir Range, Pakistan: Exploring Status and Conservation Hotspots

Flagship Species of the Pamir Mountain Range, Pakistan: Exploring Status and Conservation Hotspots Final Report (January 2012 – July 2013) ©SLF/UMB/WCS Submitted by: Jaffar Ud Din Country Program Manager, Snow Leopard Foundation, Pakistan Page 1 of 23 Table of Contents S# Contents Page# 1. Executive summary................................................................................................ 3-4 2. Objectives………………......................................................................................... 5 3. Methods………………………................................................................................. 5-8 4. Results…….............................................................................................................. 8-11 5. Discussion……………………................................................................................... 11-12 6. Other activities……………………………….............................................................. 12-13 7. References………………………………………….................................................... 13-15 8. Tables…………………………………....................................................................... 16-17 9. Figures…………………………………………………................................................ 17-20 10. Plates………………………………………………...................................................... 21-23 Page 2 of 23 1. Executive summary: This report outlines the findings of the project titled as “Flagship species of Pamir Mountain Range, Pakistan: Exploring Status and Conservation Hotspots” funded by Snow Leopard Conservation Grant Program -

Langdon Warner at Dunhuang: What Really Happened? by Justin M

ISSN 2152-7237 (print) ISSN 2153-2060 (online) The Silk Road Volume 11 2013 Contents In Memoriam ........................................................................................................................................................... [iii] Langdon Warner at Dunhuang: What Really Happened? by Justin M. Jacobs ............................................................................................................................ 1 Metallurgy and Technology of the Hunnic Gold Hoard from Nagyszéksós, by Alessandra Giumlia-Mair ......................................................................................................... 12 New Discoveries of Rock Art in Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor and Pamir: A Preliminary Study, by John Mock .................................................................................................................................. 36 On the Interpretation of Certain Images on Deer Stones, by Sergei S. Miniaev ....................................................................................................................... 54 Tamgas, a Code of the Steppes. Identity Marks and Writing among the Ancient Iranians, by Niccolò Manassero .................................................................................................................... 60 Some Observations on Depictions of Early Turkic Costume, by Sergey A. Yatsenko .................................................................................................................... 70 The Relations between China and India -

Mountain Pass Is a Navigable Rout Through a Range Or Over a Ridge. It Is in the Zaskar Range of Jammu & Kashmir at an Elevation of 3528 M

Mountain pass is a navigable rout through a range or over a ridge. It is in the Zaskar range of Jammu & Kashmir at an elevation of 3528 m. Mountain pass is a connectivity route through the mountain run. It connects Shrinagar with Kargil and Leh. Mountain pass are often found just above the source of river, constituting Road passing through this pass has been designated at the National Highway (NH-1D) a drainage divide. A pass me be very short, consisting of steep slope to the top of the Zoji La pass pass or maybe a valley many kilometer long. Mintaka pass Introduction Located in the Karakoram range at an elevation of 4709 m At the tri-junction of the Indian, Chinese & Afghan Border. Mountain Passes in India Aghil pass Karakoram pass Located in the Karakoram range at an elevation of about 4805 m This pass separates the Ladakh region in India with the Shaksgam Located in the Karakoram range at an elevation of 5540 m. valley in China. Act as a passage between India china with the help of Khardung La It is situated to the north of Mount Godwin-Austin in the Karakoram the Karakoram Highway. The route was part of the ancient Silk route active in history Located in the Karakoram range at an elevation of 5359 m in the Ladakh region. It is the highest motorable pass in the countary. It connect Leh and Siachen glaciers. Located in the Himalayan range in Jammu & Kashmir at an elevation Located in the Himalayan range in the state of Himachal Pradesh,. -

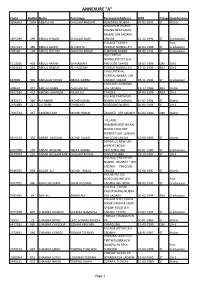

List of Candidates for Physical Efficiency Test for the Post of Wildlife/Forest Guard in Alphabetical

ANNEXURE "A" CanId RollNo Name Parentage PermanentAddress DOB CategoryQualification 9396603 1004 ABBASS ALI GHULAM HASSAN BOGDANG NUBRA 05-02-2001 ST Matric KHALKHAN MANAY- KHANG NEAR JAMA MASJID LEH LADAKH 1855389 499 ABDUL KHALIQ GHULAM NABI 194101 12-12-1994 ST Graduation VILLAGE TYAKSHI Post 1557437 389 ABDUL QADIR ALI MOHD TURTUK NUBRA LEH 30-04-1988 ST Graduation 778160 158 ABDUL QAYUM GHULAM MOHD SUMOOR NUBRA 04-02-1991 ST Graduation R/O TURTUK NURBA,DISTICT LEH, 5113265 402 ABDUL RAHIM GH HASSAN PIN CODE 194401 28-03-1996 OM 10+2 6309413 334 ABDUL RAWUF ALI HUSSAIN TURTUK NUBRA LEH 17-12-1995 RBA 10+2 CHULUNGKHA, TURTUK, NUBRA, LEH 697699 301 ABDULLAH KHAN ABDUL KARIM LADAKH-194401 02-11-1991 ST Graduation CHUCHOT GONGMA 408661 912 ABID HUSSAIN GHULAM ALI LEH LADAKH 19-12-1986 RBA Matric 4917184 412 ABIDAH KHANUM NAJAF ALI TYAKSHI 04-03-1996 RBA 10+2 VILLAGE PARTAPUR 3432671 346 ALI AKBAR MOHD KARIM NUBRA LEH LADAKH 15-07-1994 ST Matric 2535888 217 ALI SHAH GH MOHD BOGDANG NUBRA 05-05-1996 ST 10+2 7345534 337 AMAMULLAH MOHD YAQUB ZANGSTI LEH LADAKH 10-03-1999 OM Matric VILLAGE: RAMBIRPUR(THIKSAY) BLOCK:CHUCHOT DISTRICT:LEH LADAKH 6615129 355 ANSAR HUSSAIN MOHD SAJAD PIN CODE:194101 15-06-1995 ST Matric MOHALLA NEW LEH AIRPORT ROAD 6952008 107 ANSAR HUSSAIN ABDUL KARIM SKALZANGLING 01-01-1989 ST Graduation 4370703 255 ANSAR HUSSAIN MIR GHULAM MOHD DISKET NUBRA 23-10-1997 ST 10+2 VILLAGE: PARTAPUR NUBRA DISTRICT : LEH LADAKH PIN CODE: 9346395 993 ASGAR ALI MOHD ISMAIL 194401 25-06-1997 ST Matric HOUSE NO 102 NORGYASLING LEH Post -

Selection List No.1 of Candidates Who Have Applied for Admission to B.Ed

Selection List No.1 of candidates who have applied for admission to B.Ed. Offered through Directorate of Distance Education session-2020 for Leh Chapter Total Sr. Roll No. Name Parentage Address District Cat. Graduation MM MO out of 90 Masters MM MO out of 10 out of 100 OM TASHI NAWANG R/O DURBUK, 1 20612463 YANGZES GALCHAN NEMGO LEH ST BSC 8 7.5 93.75 NYOMA NIMA PHUNTSOK CHANGTHANG, 2 20613648 PALDEN DORJAY LEH LADAKH LEH RBA BA 500 400 72.00 MASTERS 600 458 7.63 79.63 #A021 SPECIAL DECHEN TSERING HOUSING COLONY 3 20611411 CHOSKIT CHOSDAN DISKET TSAL LEH ST BSCAGRI 1000 784 78.40 NAWANG SONAM KHEMI NUBRA LEH 4 20612077 NAMGYAL DORJEY LADAKH UT LEH ST BA 3600 2786 77.39 NUBRA CHARASA TSERING DEACHEN LEH UT LADAKH 5 20611533 LANZES PALJOR 194401 LEH ST BA 3600 2761 76.69 LAKSAM SAMTAN 6 20611628 DAWA KHENRAP SHANG LEH ST BA 3600 2757 76.58 STANZIN MUTUP ZOTPA SKARA LEH 7 20610026 ANGMO GURMET LADAKH LEH ST BSC 3300 2533 69.08 MASTERS 2400 1722 7.18 76.26 RAGASHA PA RIGZEN SKARMA CHUCHOT YOKMA 8 20612617 ANGMO PHUNTSOG LEH LEH ST BSC 3500 2633 75.23 STANZIN KONCHOK VILLAGE 9 20612598 ANGMO CHOSPHEL SKURBUCHAN LEH ST BSC 10 7.5 75.00 JIGMET PHUNCHOK 10 20612618 LAHZES TUNDUP STOK LEH LEH ST BA 2400 1799 74.96 TSEWANG NAWANG VILLAGE 11 20612596 YOUROL TASHI SKURBUCHAN LEH ST BSC 10 7.4 74.00 SONAM TSERING VILLAGE HANU 12 20610838 ANGCHUK DORJAY YOKMA LEH ST BA 3600 2658 73.83 KONCHOK TSEWANG DURBUK TANGTSE 13 20611554 NAMGAIL CHOSPEL LEH UT LADAKH LEH ST BA 3600 2627 72.97 VILLAGE SUDDIQA BOGDANG BLOCK 14 20612745 BANO MOHD MUSSA NUBRA LEH ST BSC 10 7.2 72.00 PHUTITH SONAM MERAK PANGONG 15 20612066 DOLMA PAMBAR LEH LADAKH LEH ST BTECH 800 576 72.00 Selection List No.1 of candidates who have applied for admission to B.Ed. -

Expression of Ladakhi Cultural Regionality: ラダック文化にみる地域

Kanazawa Seiryo University Bulletin of the Humanities Vol.3 No.1, pp.25-38, 2018 Expression of Ladakhi Cultural Regionality: Viewed from Language and Local Rituals Takako YAMADA† Abstract Ladakhi culture cannot be discussed without reference to its relations to Tibet and Tibetan culture. The Ladakh dynasty started its rule by one of the three sons of Skyid lde nyima gon (or Nyima gon), the great-grandson of Lang Darma who was the last emperor of the Old Tibetan Empire, also known as an anti-Buddhist king. Later, various Tibetan Buddhist schools have spread subsequently to Ladakh and converted its residents to Tibetan Buddhism. However, when viewed in terms as its polity as a kingdom, Ladakh has not always maintained friendly relations with Tibet, as exemplified by the war that took place in the 17th century between Ladakh and a joint Tibetan-Mongolian army. Rather, Ladakh has been ruled by an independent polity different from that of Tibet, and has maintained its cultural identity. This paper aims to reveal the regionality of contemporary Ladakhi culture as well as its Pan-Tibetan aspects, dealing with how the cultural identity of the Ladakhi is expressed in terms of language and religion, specifically basing on local ritual tradition as well as activities engaged in by the Students’ Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL) in order to maintain Ladakhi culture and language. Keywords Ladakhi culture, regionality, language, local rituals ラダック文化にみる地域性の表出 ─ 言語とローカルな儀礼実践から ─ 山田 孝子† キーワード ラダック文化,地域性,言語,ローカルな儀礼実践 † [email protected] (Faculty of Humanities, Kanazawa Seiryo University) - 25 - Expression of Ladakhi Cultural Regionality 1. -

Indo-Pakistan Relations (1972-1977) Baderunissa Channah University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1978 Indo-Pakistan relations (1972-1977) Baderunissa Channah University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Channah, Baderunissa, "Indo-Pakistan relations (1972-1977)" (1978). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2531. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2531 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDO-PAKISTAN RELATIONS (1972-1977) A Thesis Presented By BADERUNISSA CHANNAH Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 1 978 Political Science INDO-PAKISTAN RELATIONS - ( 1972 1977 ) A Thesis Presented By BADERUNISSA CHANNAH Approved as to style and content by: Dr. Anwar H. Syed Chairperson of Committee Dr. Gerard Braunthal , Member ^ '/ . Dr. Glen Gordon, Chairman Department of Political Science DEDICATION To my Mother and Father-- with all my love. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION The Background of Indo-Paki stan Tension ] II. MAJOR DISPUTES BETWEEN INDIA AND PAKISTAN 1 -3 The Kashmir Dispute and the First War in Kashmir 1 948 “49 Rann of Kutch Dispute .... The War of 1965 !*.!!!!!! The 1971 War and Disintegration of Pakistan !!!”'* War Between India and Pakistan !!!.'!! III. ATTITUDE OF BIG POWERS TOWARDS INDIA AND PAKISTAN India's and Pakistan's Relations with the United States . -

From Benaras to Leh - the Trade and Use of Silk-Brocade

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2002 From Benaras to Leh - the trade and use of silk-brocade Monisha Ahmed Oxford University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Ahmed, Monisha, "From Benaras to Leh - the trade and use of silk-brocade" (2002). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 498. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/498 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. From Benaras to Leh - the trade and use of silk-brocade / by Monisha Ahmed ( < A weaver in Benaras sits at his pit loom meticulously creating a textile piece of Mahakala. the god of protection for Buddhists. A lama at the festival ( 'cham) at Hemis monastery performs the religious dance, the Mahakala { image on his apron (pang-kheb} gazing out at the devotees as he pirouettes around the courtyard. The two descriptions given above demonstrate the beginning and end of the journey of silk- brocades from Benaras to Leh. This paper looks at the historical context of the trade in silk- ( brocades from Benaras to Leh, and discusses how this trade first started. It presents how these fabrics are made in Benaras and discusses their various uses in Ladakh. Finally, it examines the contemporary status of the trade and the continued importance of silk-brocades in the lives of Buddhist Ladakhis. -

New Thinking on Persistent Security Challenges in the Asia Pacific an NCAFP Edited Volume

New Thinking on Persistent Security Challenges in the Asia Pacific An NCAFP Edited Volume Introduction by Susan A. Thornton Cho Byung-jae | Richard J. Heydarian | Jimbo Ken Kim Jina | Keith Luse | Oba Mie | Xin Qiang Zhang Tuosheng | James P. Zumwalt April 2021 Diplomacy in Action Since 1974 Our Mission he National Committee on American Foreign Policy (NCAFP) was founded in 1974 by Professor Hans J. Morgenthau and others. It is a nonprofit policy organization dedicated to T the resolution of conflicts that threaten US interests. Toward that end, the NCAFP identifies, articulates, and helps advance American foreign policy interests from a nonpartisan perspective within the framework of political realism. American foreign policy interests include: • Preserving and strengthening national security; • Supporting the values and the practice of political, religious, and cultural pluralism; • Advancing human rights; • Addressing non-traditional security challenges such as terrorism, cyber security and climate change; • Curbing the proliferation of nuclear and other unconventional weapons; and • Promoting an open and global economy. The NCAFP fulfills its mission through Track I 1⁄2 and Track II diplomacy. These closed-door and off-the-record conferences provide opportunities for senior US and foreign officials, subject experts, and scholars to engage in discussions designed to defuse conflict, build confidence, and resolve problems. Believing that an informed public is vital to a democratic society, the National Committee offers educational programs and issues a variety of publications that address security challenges facing the United States. Critical assistance for this volume was provided by Ms. Rorry Daniels, Deputy Project Director of the NCAFP’s Forum on Asia-Pacific Security (FAPS); Ms. -

The Chinese People's Liberation Army in 2025

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army in 2025 The Chinese People’s The Chinese People’s Liberation Army in 2025 FOR THIS AND OTHER PUBLICATIONS, VISIT US AT http://www.carlisle.army.mil/ U.S. ARMY WAR COLLEGE David Lai Roy Kamphausen Editors: Editors: UNITED STATES Roy Kamphausen ARMY WAR COLLEGE PRESS David Lai This Publication SSI Website USAWC Website Carlisle Barracks, PA and The United States Army War College The United States Army War College educates and develops leaders for service at the strategic level while advancing knowledge in the global application of Landpower. The purpose of the United States Army War College is to produce graduates who are skilled critical thinkers and complex problem solvers. Concurrently, it is our duty to the U.S. Army to also act as a “think factory” for commanders and civilian leaders at the strategic level worldwide and routinely engage in discourse and debate concerning the role of ground forces in achieving national security objectives. The Strategic Studies Institute publishes national security and strategic research and analysis to influence policy debate and bridge the gap between military and academia. The Center for Strategic Leadership and Development CENTER for contributes to the education of world class senior STRATEGIC LEADERSHIP and DEVELOPMENT leaders, develops expert knowledge, and provides U.S. ARMY WAR COLLEGE solutions to strategic Army issues affecting the national security community. The Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute provides subject matter expertise, technical review, and writing expertise to agencies that develop stability operations concepts and doctrines. U.S. Army War College The Senior Leader Development and Resiliency program supports the United States Army War College’s lines of SLDR effort to educate strategic leaders and provide well-being Senior Leader Development and Resiliency education and support by developing self-awareness through leader feedback and leader resiliency.