From Benaras to Leh - the Trade and Use of Silk-Brocade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Himalaya Insight Special

HIMALAYA INSIGHT SPECIAL Duration: 08 Nights / 09 Days (Validity: May to September) Destinations Covered: Leh, Monasteries, Sham Valley, Indus Valley, Tsomoriri Lake, Tsokar Lake, Pangong Lake, Turtuk & Nubra Valley The Journey Begins Now! DAY 01: ARRIVE LEH Arrival Leh Kushok Bakula Airport (This must be one of the MOST SENSATIONAL FLIGHTS IN THE WORLD. On a clear day from one side of the aircraft can be seen in the distance the peaks of K2, Nanga Parbat, Gasherbrum and on the other side of the aircraft, so close that you feel you could reach out and touch it, is the Nun Kun massif.) Upon arrival you will met by our representative and transfer to Hotel for Check in. Complete day for rest and leisure to acclimatize followed by Welcome tea or Coffee at the Hotel. Evening Visit to LEH MARKET & SHANTI STUPA. Dinner & Overnight at Hotel. DAY 02: LEH TO SHAM VALLEY (92 KMS / 4 HRS) After breakfast you drive downstream along the River Indus on Leh – Kargil Highway. Enroute visiting GURUDWARA PATTHAR SAHIB Nestled deep in the Himalayas, which was built by the Lamas of Leh in 1517 to commemorate the visit of Guru Nanak Dev. A drive of another 4 km took us to MAGNETIC HILL which defies the law of gravity. It has been noticed that when a vehicle is parked on neutral gear on this metallic road the vehicle slides up & further Driving through a picturesque landscape we reached the CONFLUENCE OF THE INDUS AND ZANSKAR RIVER 4 km before Nimmu village, Just before Saspul a road to the right takes you for your visit to the LIKIR MONASTERY. -

Photographic Archives in Paris and London Pascale Dollfus

Photographic archives in Paris and London Pascale Dollfus To cite this version: Pascale Dollfus. Photographic archives in Paris and London. European bulletin of Himalayan research, University of Cambridge ; Südasien-Institut (Heidelberg, Allemagne)., 1999, Special double issue on photography dedicated to Corneille Jest, pp.103-106. hal-00586763 HAL Id: hal-00586763 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00586763 Submitted on 10 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. EBHR 15- 16. 1998- 1999 PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVES IN PARIS AND epal among the Limbu. Rai. Chetri. Sherpa, Bhotiya and Sunuwar. LONDO ' Both these collections encompa'\s pictures of land flY PA CALE DOLL FUSS scapes. architecture. techniques. agriculture. herding, lrade, feslivals. shaman practices. rites or passage. etc. In addition to these major collecti ons. once can find I. PUOTOGRAPfIIC ARCIUVES IN PARIS 350 photographs taken in 1965 by Jaeques Millot. (director of the RCP epal) in the Kathmandu Valley. Photographic Library ("Phototheque"), Musee de approx. 110 photographs (c. 1966-67) by Mireille Helf /'lIommc. fer. related primari Iy to musicians caSles, 45 photo 1'1. du Trocadero. Paris 750 16. graphs (1967-68) by Marc Gaborieau. -

O Level ST Candidates (Leh)

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ELECTRONICS & INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY,NIELIT J&K SUB CENTRE LEH LIST OF 'O'LEVEL STUDENTS BATCH:-DECEMBER (2013) S.NO App.No. Regn.No Level Name Father/Guardian Name Category Date of Birth Address 1 ROIT0614001604 964750 O KANIS FATIMA HASSAN ALI ST 29-जनवर -89 CHUCHOT LEH 2 ROIT0614002115 964759 O HASSINA BANO GHULAM HUSSAIN ST 02-अगत -92 SHEY SHEY 3 ROIT0614002075 964604 O NAMGYAL DOLMA SONAM THUKJEE ST 11-माच -95 HUNDER NUBRA LEH 4 ROIT0614002131 964610 O GULNAZ FATIMA MIRZA ASSADULLAH ST 11-मई -90 SHEY LEH 5 ROIT0614002113 964758 O SALEEM RAZA MOHD BAQIR ST 06-जनवर -89 SHEY SHEY 6 ROIT0614001595 964748 O HALIMA BANO GHULAM MOHD ST 13-मई -96 BASHAKA CHUCHOT YOKMA LEH 7 ROIT0614002061 964829 O ESHEY DOLMA TASHI WANGAIL ST 03-दसबर -89 TSATI SUMOOR NUBRA 8 ROIT0614002117 964608 O DEACHEN DOLMA TSERING NORBOO ST 21-माच -90 ZUNGPA CHAMSHEN SUMOOR NUBRA 9 ROIT0614001927 964600 O DORJAY DOLMA THUGJAY TUNDUP ST 05-जून -93 SHARA SHARA 10 ROIT0614001931 964602 O RIGZEN DOLMA TSEWANG CHONJOR ST 10-फरवर -92 SHANG LEH 11 ROIT0614002124 964834 O TSERING ANGMO TSEWANG DORJAY ST 28-जून -94 SUMOOR NUBRA LEH 12 ROIT0614002103 964832 O RIGZIN YANGDOL TASHI WANGIAL ST 01-नवबर -92 CHOGLAMSAR ZAMPA LEH 13 ROIT0614002131 964610 O KANIZ FATIMA MEHDI ALI ST 11-मई -90 SHEY LEH 14 ROIT0614002111 964607 O SONAM YANGCHAN TONDUP NAMGAIL ST 01-मई -93 PHUKPOCHEY SUMOOR NUBRA 15 ROIT0614002123 964760 O SHAHEEN KOUSAR MOHD YASSIN ST 20-फरवर -84 THASGAN THLINA KARGIL 16 ROIT0614002071 964603 O ANWAR HUSSAIN MIRZA HADI ST 03-जनवर -84 CHUCHOT YOKMA -

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 “STATISTICAL HANDBOOK” DISTRICT KARGIL UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH FOR THE YEAR 2018-19 RELEASED BY: DISTRICT STATISTICAL & EVALUATION OFFICE KARGIL D.C OFFICE COMPLEX BAROO KARGIL J&K. TELE/FAX: 01985-233973 E-MAIL: [email protected] Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH, Chairman/ Chief Executive Councilor, LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985 233827, 233856 Message It gives me immense pleasure to know that District Statistics & Evaluation Agency Kargil is coming up with the latest issue of its ideal publication “Statistical Handbook 2018-19”. The publication is of paramount importance as it contains valuable statistical profile of different sectors of the district. I hope this Hand book will be useful to Administrators, Research Scholars, Statisticians and Socio-Economic planners who are in need of different statistics relating to Kargil District. I appreciate the efforts put in by the District Statistics & Evaluation Officer and the associated team of officers and officials in bringing out this excellent broad based publication which is getting a claim from different quarters and user agencies. Sd/= (Feroz Ahmed Khan ) Chairman/Chief Executive Councilor LAHDC, Kargil Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH District Magistrate, (Deputy Commissioner/CEO) LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985-232216, Tele Fax: 232644 Message I am glad to know that the district Statistics and Evaluation Office Kargil is releasing its latest annual publication “Statistical Handbook” for the year 2018- 19. The present publication contains statistics related to infrastructure as well as Socio Economic development of Kargil District. -

Ladakh Studies

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES LADAKH STUDIES _ 19, March 2005 CONTENTS Page: Editorial 2 News from the Association: From the Hon. Sec. 3 Nicky Grist - In Appreciation John Bray 4 Call for Papers: 12th Colloquium at Kargil 9 News from Ladakh, including: Morup Namgyal wins Padmashree Thupstan Chhewang wins Ladakh Lok Sabha seat Composite development planned for Kargil News from Members 37 Articles: The Ambassador-Teacher: Reflections on Kushok Bakula Rinpoche's Importance in the Revival of Buddhism in Mongolia Sue Byrne 38 Watershed Development in Central Zangskar Seb Mankelow 49 Book reviews: A Checklist on Medicinal & Aromatic Plants of Trans-Himalayan Cold Desert (Ladakh & Lahaul-Spiti), by Chaurasia & Gurmet Laurent Pordié 58 The Issa Tale That Will Not Die: Nicholas Notovitch and his Fraudulent Gospel, by H. Louis Fader John Bray 59 Trance, Besessenheit und Amnesie bei den Schamanen der Changpa- Nomaden im Ladakhischen Changthang, by Ina Rösing Patrick Kaplanian 62 Thesis reviews 63 New books 66 Bray’s Bibliography Update no. 14 68 Notes on Contributors 72 Production: Bristol University Print Services. Support: Dept of Anthropology and Ethnography, University of Aarhus. 1 EDITORIAL I should begin by apologizing for the fact that this issue of Ladakh Studies, once again, has been much delayed. In light of this, we have decided to extend current subscriptions. Details are given elsewhere in this issue. Most recently we postponed publication, because we wanted to be able to announce the place and exact dates for the upcoming 12th Colloquium of the IALS. We are very happy and grateful that our members in Kargil will host the colloquium from July 12 through 15, 2005. -

6 Nights & 7 Days Leh – Nubra Valley (Turtuk Village)

Jashn E Navroz | Turtuk, Ladakh | Dates 25March-31March’18 |6 Nights & 7 Days Destinations Leh Covered – Nubra : Leh Valley – Nubra (Turtuk Valley V illage)(Turtuk– Village Pangong ) – Pangong Lake – Leh Lake – Leh Trip starts from : Leh airport Trip starts at: LehTrip airport ends at |: LehTrip airport ends at: Leh airport “As winter gives way to spring, as darkness gives way to light, and as dormant plants burst into blossom, Nowruz is a time of renewal, hope and joy”. Come and experience this festive spirit in lesser explored gem called Turtuk. The visual delights would be aptly complemented by some firsthand experiences of the local lifestyle and traditions like a Traditional Balti meal combined with Polo match. During the festival one get to see the flamboyant and vibrant tribe from Balti region, all dressed in their traditional best. Day 01| Arrive Leh (3505 M/ 11500 ft.) Board a morning flight and reach Leh airport. Our representative will receive you at the terminal and you then drive for about 20 minutes to reach Leh town. Check into your room. It is critical for proper acclimatization that people flying in to Leh don’t indulge in much physical activity for at least the first 24hrs. So the rest of the day is reserved for relaxation and a short acclimatization walk in the vicinity. Meals Included: L & D Day 02| In Leh Post breakfast, visit Shey Monastery & Palace and then the famous Thiksey Monastery. Drive back and before Leh take a detour over the Indus to reach Stok Village. Enjoy a traditional Ladakhi meal in a village home later see Stok Palace & Museum. -

The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh

The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’ Laurianne Bruneau & John Vincent Bellezza I. An introduction to the rock art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh his paper examines common thematic and esthetic features discernable in the rock art of the western portion of the T Tibetan plateau.1 This rock art is international in scope; it includes Ladakh (La-dwags, under Indian jurisdiction), Tö (Stod) and the Changthang (Byang-thang, under Chinese administration) hereinafter called Upper Tibet. This highland rock art tradition extends between 77° and 88° east longitude, north of the Himalayan range and south of the Kunlun and Karakorum mountains. [Fig.I.1] This work sets out the relationship of this art to other regions of Inner Asia and defines what we call the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’. The primary materials for this paper are petroglyphs (rock carvings) and pictographs (rock paintings). They comprise one of the most prolific archaeological resources on the Western Tibetan Plateau. Although pictographs are quite well distributed in Upper 1 Bellezza would like to heartily thank Joseph Optiker (Burglen), the sole sponsor of the UTRAE I (2010) and 2012 rock art missions, as well as being the principal sponsor of the UTRAE II (2011) expedition. He would also like to thank David Pritzker (Oxford) and Lishu Shengyal Tenzin Gyaltsen (Gyalrong Trokyab Tshoteng Gön) for their generous help in completing the UTRAE II. Sponsors of earlier Bellezza expeditions to survey rock art in Upper Tibet include the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation (New York) and the Asian Cultural Council (New York). -

THE EARLY BUDDHIST HERITAGE of LADAKH RECONSIDERED CHRISTIAN LUCZANITS Much Ofwhat Is Generally Considered to Represent the Earl

THE EARLY BUDDHIST HERITAGE OF LADAKH RECONSIDERED CHRISTIAN LUCZANITS Much ofwhat is generally considered to represent the earliest heritage of Ladakh cannot be securely dated. It even cannot be said with certainty when Buddhism reached Ladakh. Similarly, much ofwhat is recorded in inscriptions and texts concerning the period preceding the establishment of the Ladakhi kingdom in the late 151h century is either fragmentary or legendary. Thus, only a comparative study of these records together 'with the architectural and artistic heritage can provide more secure glimpses into the early history of Buddhism in Ladakh. This study outlines the most crucial historical issues and questions from the point of view of an art historian and archaeologist, drawing on a selection of exemplary monuments and o~jects, the historical value of which has in many instances yet to be exploited. vVithout aiming to be so comprehensive, the article updates the ground breaking work of A.H. Francke (particularly 1914, 1926) and Snellgrove & Skorupski (1977, 1980) regarding the early Buddhist cultural heritage of the central region of Ladakh on the basis that the Alchi group of monuments l has to be attributed to the late 12 and early 13 th centuries AD rather than the 11 th or 12 th centuries as previously assumed (Goepper 1990). It also collects support for the new attribution published by different authors since Goepper's primary article. The nmv fairly secure attribution of the Alchi group of monuments shifts the dates by only one century} but has wide repercussions on I This term refers to the early monuments of Alchi, rvIangyu and Sumda, which are located in a narrow geographic area, have a common social, cultural and artistic background, and may be attIibuted to within a relatively narrow timeframe. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 25:2 — Spring/Summer 2013 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Spring 2013 Textile Society of America Newsletter 25:2 — Spring/Summer 2013 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 25:2 — Spring/Summer 2013" (2013). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 66. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/66 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Textile VOLUME 25 n NUMBER 2 n SPRING/SIMMER, 2013 Society of America New TSA Program: Textiles Close Up CONTENTS First event in this new series: For our inaugural workshop, is it…The installation is enrap- participants will join curator and turing, as intricately patterned 1 Textiles Close Up Indonesian Textiles TSA member Dr. Ruth Barnes as the Indonesian textiles and 3 From the President at the Yale University for an exclusive day-visit to the Borneo carvings that fill it.” 4 TSA News, TSA Study Tours Art Gallery Yale University Art Gallery, New After the gallery tour, par- Haven, CT, and its rich collec- ticipants will gather for an à-la- 7 TSA Member News MAY 16, 2013 tion of textiles from Indonesia. carte luncheon at the Union 9 In Memoriam: Irene Good The small-group visit begins at League Café. -

French Silk Varieties in Eighteenth Century

Asian Social Science; Vol. 17, No. 1; 2021 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education French Silk Varieties in Eighteenth Century Jialiang Lu1 & Feng Zhao1,2 1 School of Fashion and Art Design, Donghua University, Shanghai, China 2 China National Silk Museum, Hangzhou, China Correspondence: Feng Zhao, China National Silk Museum, Hangzhou, China. Tel: 86-139-5806-6182. E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 6, 2020 Accepted: December 19, 2020 Online Published: December 30, 2020 doi:10.5539/ass.v17n1p53 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v17n1p53 Abstract The design of French silk was very exquisite. Which has formed a clear specification and strict classification system even teaching materials in Eighteenth Century. Based on the existing material objects and teaching materials, this paper systematically sorts out the variety system of French silk fabrics, makes a detailed classification of varieties, and analyzes the political factors of the prosperity and development of French silk industry in the 18th century. 1. Preface The history of silk in France was not very long, but it indeed reached the peak of the world and was extremely glorious. Especially around the 18th century, which can be divided into four periods. For starters, the country supported silk industry by making policies under king Louis XIV's reign, and then, lots of technique innovations appeared during the reign of king Louis XV. What’s more, flourishing period of silk in France started when Louis XVI succeeded. However, it was the French Revolution that made a huge decline of silk industry. -

List of Candidates for Physical Efficiency Test for the Post of Wildlife/Forest Guard in Alphabetical

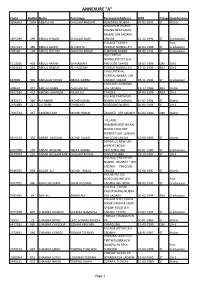

ANNEXURE "A" CanId RollNo Name Parentage PermanentAddress DOB CategoryQualification 9396603 1004 ABBASS ALI GHULAM HASSAN BOGDANG NUBRA 05-02-2001 ST Matric KHALKHAN MANAY- KHANG NEAR JAMA MASJID LEH LADAKH 1855389 499 ABDUL KHALIQ GHULAM NABI 194101 12-12-1994 ST Graduation VILLAGE TYAKSHI Post 1557437 389 ABDUL QADIR ALI MOHD TURTUK NUBRA LEH 30-04-1988 ST Graduation 778160 158 ABDUL QAYUM GHULAM MOHD SUMOOR NUBRA 04-02-1991 ST Graduation R/O TURTUK NURBA,DISTICT LEH, 5113265 402 ABDUL RAHIM GH HASSAN PIN CODE 194401 28-03-1996 OM 10+2 6309413 334 ABDUL RAWUF ALI HUSSAIN TURTUK NUBRA LEH 17-12-1995 RBA 10+2 CHULUNGKHA, TURTUK, NUBRA, LEH 697699 301 ABDULLAH KHAN ABDUL KARIM LADAKH-194401 02-11-1991 ST Graduation CHUCHOT GONGMA 408661 912 ABID HUSSAIN GHULAM ALI LEH LADAKH 19-12-1986 RBA Matric 4917184 412 ABIDAH KHANUM NAJAF ALI TYAKSHI 04-03-1996 RBA 10+2 VILLAGE PARTAPUR 3432671 346 ALI AKBAR MOHD KARIM NUBRA LEH LADAKH 15-07-1994 ST Matric 2535888 217 ALI SHAH GH MOHD BOGDANG NUBRA 05-05-1996 ST 10+2 7345534 337 AMAMULLAH MOHD YAQUB ZANGSTI LEH LADAKH 10-03-1999 OM Matric VILLAGE: RAMBIRPUR(THIKSAY) BLOCK:CHUCHOT DISTRICT:LEH LADAKH 6615129 355 ANSAR HUSSAIN MOHD SAJAD PIN CODE:194101 15-06-1995 ST Matric MOHALLA NEW LEH AIRPORT ROAD 6952008 107 ANSAR HUSSAIN ABDUL KARIM SKALZANGLING 01-01-1989 ST Graduation 4370703 255 ANSAR HUSSAIN MIR GHULAM MOHD DISKET NUBRA 23-10-1997 ST 10+2 VILLAGE: PARTAPUR NUBRA DISTRICT : LEH LADAKH PIN CODE: 9346395 993 ASGAR ALI MOHD ISMAIL 194401 25-06-1997 ST Matric HOUSE NO 102 NORGYASLING LEH Post -

The Changing Face of Religious Coexistence in Ladakh

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2015 More Religious and Less Moral: The hC anging Face of Religious Coexistence in Ladakh Henry Wilson-Smith SIT Graduate Institute - Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, and the Islamic Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wilson-Smith, Henry, "More Religious and Less Moral: The hC anging Face of Religious Coexistence in Ladakh" (2015). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2225. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2225 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. More Religious and Less Moral: The Changing Face of Religious Coexistence in Ladakh Henry Wilson-Smith Academic Director: Onians, Isabelle Senior Faculty Advisor: Decleer, Hubert Independent Study Project Advisor: Bray, John Stanford University International Relations and AnthropoloGy Asia, India, Ladakh, Kargil, Chiktan and Kuksho Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for Nepal: Tibetan and Himalayan Peoples, SIT Study Abroad, Autumn 2015 0 1 Abstract Ladakh hosts a mixed population of Buddhists and Muslims that belies its popular image as a solely Buddhist replica of Tibet. Despite its unique history of reliGious integration, new pressures linked to Globalisation are pullinG the communities apart, with occasional and previously unheard-of communal conflict breakinG out in recent decades.