Sadagat Aliyeva

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOHN ASHBERY Arquivo

SELECTED POEMS ALSO BY JOHN ASHBERY Poetry SOME TREES THE TENNIS COURT OATH RIVERS AND MOUNTAINS THE DOUBLE DREAM OF SPRING THREE POEMS THE VERMONT NOTEBOOK SELF-PORTRAIT IN A CONVEX MIRROR HOUSEBOAT DAYS AS WE KNOW SHADOW TRAIN A WAVE Fiction A NEST OF NINNIES (with James Schuyler) Plays THREE PLAYS SELECTED POEMS JOHN ASHBERY ELISABt'Tlf SIFTON BOOKS VIKING ELISABETH SIYrON BOOKS . VIKING Viking Penguin Inc., 40 West 23rd Street, New York, New York 10010, U.S.A. Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia Penguin Books Canada Limited, 2801 John Street, Markham, Ontario, Canada UR IB4 Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand Copyright © John Ashbery, 1985 All rights reserved First published in 1985 by Viking Penguin Inc. Published simultaneously in Canada Page 349 constitutes an extension ofthis copyright page. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Ashbery, John. Selected poems. "Elisabeth Sifton books." Includes index. I. Title. PS350l.S475M 1985 811'.54 85-40549 ISBN 0-670-80917-9 Printed in the United States of America by R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company, Ilarrisonburg, Virginia Set in Janson Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means· (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission ofboth the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book. CONTENTS From SOME TREES Two Scenes 3 Popular Songs 4 The Instruction Manual 5 The Grapevine 9 A Boy 10 ( ;Iazunoviana II The Picture of Little J. -

Download English

www.smartkeeda.com | h ttps://testzone.smartkeeda.com/# SBI | RBI | IBPS |RRB | SSC | NIACL | EPFO | UGC NET |LIC | Railways | CLAT | RJS Join us Testzone presents Full-Length Current Affairs Mock Test Series Month-wise February MockDrill100 PDF No. 4 (PDF in English) Test Launch Date: 25th Feb 2021 Attempt Test No 4 Now! www.smartkeeda.com | h ttps://testzone.smartkeeda.com/# SBI | RBI | IBPS |RRB | SSC | NIACL | EPFO | UGC NET |LIC | Railways | CLAT | RJS Join us An important message from Team Smartkeeda Hi Folks! We hope you all are doing well. We would like to state here that this PDF is meant for preparing for the upcoming MockDrill Test of February 2021 Month at Testzone. In this Current Affairs PDF we have added all the important Current Affairs information in form of ‘Key-points’ which are crucial if you want to score a high rank in Current Affairs Mocks at Testzone. Therefore, we urge you to go through each piece of information carefully and try to remember the facts and figures because the questions to be asked in the Current Affairs MockDrill will be based on the information given in the PDF only. We hope you will make the best of use of this PDF and perform well in MockDrill Tests at Testzone. All the best! Regards Team Smartkeeda मा셍टकीड़ा 셍ीम की ओर से एक मह配वपू셍 ट सꅍदेश! मित्रⴂ! हि आशा करते हℂ की आप सभी वथ और कु शल हⴂगे। इस सन्देश के िाध्यि से हि आपसे यह कहना चाहते हℂ की ये PDF फरवरी 2021 िाह िᴂ Testzone पर होने वाले MockDrill Test िᴂ आपकी तैयारी को बेहतर करन े के मलए उपल녍ध करायी जा रही है। इस PDF िᴂ हिने कु छ अतत आव�यक -

Sweet Colors, Fragrant Songs: Sensory Models of the Andes and the Amazon Author(S): Constance Classen Source: American Ethnologist, Vol

Sweet Colors, Fragrant Songs: Sensory Models of the Andes and the Amazon Author(s): Constance Classen Source: American Ethnologist, Vol. 17, No. 4 (Nov., 1990), pp. 722-735 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of the American Anthropological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/645710 Accessed: 14/10/2010 14:06 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and American Anthropological Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Ethnologist. http://www.jstor.org sweet colors, fragrantsongs: sensory models of the Andes and the Amazon CONSTANCE CLASSEN-McCill University Every culture has its own sensory model based on the relative importance it gives to the different senses. -

PH Braces for Fuel Crisis After Attacks on Saudi Oil Facilities

WEEKLY ISSUE @FilAmNewspaper www.filamstar.com Vol. IX Issue 545 1028 Mission Street, 2/F, San Francisco, CA 94103 Email: [email protected] Tel. (415) 593-5955 or (650) 278-0692 September 19-25, 2019 Elaine Chao (Photo: Wikimedia) VP Robredo faces resolution of her fraud, sedition cases Trump Transpo Sec. By Beting Laygo Dolor acting as presidential electoral tribu- by the Commission on Elections, which Chao under scrutiny Contributing Editor nal (PET) is expected to release the Marcos charged was an election taint- US NEWS | A2 decision on the vote recount of the ed with fraud and massive cheating. ANYTIME within the next week or 2016 elections filed by former sen- To prove his claim, Marcos so, Vice-president Leni Robredo can ator Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. against requested and was granted a manual expect a decision to be handed out in her. recount of votes in three provinces. two high-profile cases involving her. Robredo defeated Marcos by some TO PAGE A7 VP Leni Robredo (Photo: Facebook) In the first, the Supreme Court 250,000 votes based on the final tally ■ By Daniel Llanto FilAm Star Correspondent IN THE wake of the drone attacks on Saudi Arabia’s oil facilities, Foreign PH braces for fuel Affairs Sec. Teodoro Locsin Jr. said Riza Hontiveros (Photo: Facebook) the loss of half of the world’s top oil Divorce bill in producer is so serious it could affect the country “deeply” and cause the “Philip- crisis after attacks discussion at PH Senate pine boat to tip over.” PH NEWS | A3 “This is serious,” Locsin tweeted. -

Philippine Scene Demonstrating the Preparation of Favorite Filipino Dishes

Msgr. Gutierrez Miles Beauchamp Entertainment Freedom, not bondage; Wait ‘till you Annabelle prefers Yilmaz transformation... hear this one over John Lloyd for Ruffa June 26 - July 2, 2009 Thousands march vs ConAss PHILIPPINE NEWS SER- VICE -- VARIOUS groups GK Global Summit A visit to my old high school opposed to Charter change yesterday occupied the corner of Ayala Avenue and Paseo de Meloto passes torch No longer the summer of 1964, but Roxas in Makati City to show their indignation to efforts to to Oquinena and looks rewrite the Charter which they the winter of our lives in 2009 said will extend the term of toward future When I mentioned that I President Macapagal-Arroyo. would be going home to the Event organizers said there were about 20,000 people who Philippines last April, some marched and converged at of my classmates asked me the city’s financial district but to visit our old high school the police gave a conserva- and see how we could be tive crowd estimate of about of help. A classmate from 5,000. Philadelphia was also going Personalities spotted marching included Senators home at the same time and Manuel Roxas II, Benigno suggested that we meet “Noy-noy” Aquino III, Pan- with our other classmates in filo Lacson, Rodolfo Biazon, Manila. Pia Cayetano, Loren Legarda, Jamby Madrigal and Rich- By Simeon G. Silverio, Jr. ard Gordon, former Senate Publisher & Editor President Franklin Drilon and Gabriela Rep. Liza Maza, and The San Diego Rep. Jose de Venecia. They Asian Journal took turns lambasting allies of the administration who See page 5 Arellano facade (Continued on page 4) Tony Meloto addresses the crowd as Luis Oquinena and other GK supporters look on. -

Philological Sciences. Linguistics” / Journal of Language Relationship Issue 3 (2010)

Российский государственный гуманитарный университет Russian State University for the Humanities RGGU BULLETIN № 5/10 Scientific Journal Series “Philological Sciences. Linguistics” / Journal of Language Relationship Issue 3 (2010) Moscow 2010 ВЕСТНИК РГГУ № 5/10 Научный журнал Серия «Филологические науки. Языкознание» / «Вопросы языкового родства» Выпуск 3 (2010) Москва 2010 УДК 81(05) ББК 81я5 Главный редактор Е.И. Пивовар Заместитель главного редактора Д.П. Бак Ответственный секретарь Б.Г. Власов Главный художник В.В. Сурков Редакционный совет серии «Филологические науки. Языкознание» / «Вопросы языкового родства» Председатель Вяч. Вс. Иванов (Москва – Лос-Анджелес) М. Е. Алексеев (Москва) В. Блажек (Брно) У. Бэкстер (Анн Арбор) В. Ф. Выдрин (Санкт-Петербург) М. Гелл-Манн (Санта Фе) А. Б. Долгопольский (Хайфа) Ф. Кортландт (Лейден) А. Лубоцкий (Лейден) Редакционная коллегия серии: В. А. Дыбо (главный редактор) Г. С. Старостин (заместитель главного редактора) Т. А. Михайлова (ответственный секретарь) К. В. Бабаев С. Г. Болотов А. В. Дыбо О. А. Мудрак В. Е. Чернов ISSN 1998-6769 © Российский государственный гуманитарный университет, 2010 УДК 81(05) ББК 81я5 Вопросы языкового родства: Международный научный журнал / Рос. гос. гуманитар. ун-т; Рос. Акад. наук. Ин-т языкознания; под ред. В. А. Дыбо. ― М., 2010. ― № 3. ― X + 176 с. ― (Вестник РГГУ: Научный журнал; Серия «Филологические науки. Языко- знание»; № 05/10). Journal of Language Relationship: International Scientific Periodical / Russian State Uni- versity for the Humanities; Russian Academy of Sciences. Institute of Linguistics; Ed. by V. A. Dybo. ― Moscow, 2010. ― Nº 3. ― X + 176 p. ― (RSUH Bulletin: Scientific Periodical; Linguistics Series; Nº 05/10). ISSN 1998-6769 http ://journal.nostratic.ru [email protected] Дополнительные знаки: С. -

About-14-011014.Compressed.Pdf

The National Conference· ., on LGBT Equality~ Creating Change ~ The largest annual gathering of activists, organizers and leaders in the LGBT movement January 29 - February 2, 2014 Hilton Americas - Houston www.CreatingChange.org GREY GOOsE ~ COMCASToIIl& NBCUNIVERSAL . HILTON m~m ~~K \'\'odds Best'Iasriug \'Ildku WORLDWIDE "D- SOUTiiwEST -ART,r SHAV.NO" Office DEPOT. :m.wn'iE. ••,;;;;:.,t.••••".yt,::.· b1acJe. our details Cade Michals Publisher / CEO [email protected] Bill Clevenger President [email protected] Clint Hudler Director of Advertising and Sales [email protected] Steven Tilorta Writer of "I Have Issues" [email protected] Frankie Espinoza Logistics Ma1lagel' [email protected] Lance Wilcox Creative Marketillg Director [email protected] David Guerra Official Photographer [email protected] Contributing Write1's Nancy Ford, Charo BeansOeBarge OJ Chris Alien,RitchieAlien, OJJO Arnold, OJ Wild, Matthew Blanco OJ Mark 0, Ray Hili,Jacob Socialite, Curtis Braly AbOUT Magazine P.O. Box 667626 Houston, TX 77266 (713) 396-20UT (2688) [email protected] www.abOUT-Online.com www.FACEawards.org ISSN Library of Congress 2163·8470 (Print) 2163-8446 (On-Line) Copyright 2013 AbOU'," Publicarlons IAbOlTr Magaame. All rights reserved. Re- Proud Member print by permission only. Back issues avatbblc for 55.00 p(-r issue (postage included). The opinions expressed l.Iy columnists, writers ere. are their own and do nOI nC(~M- Ia a d i1yreflect rhe position of AbOllr Ma~zine. Publication of a photo or name in 9 AbOUT Magazine is nor (0 be construed as any indication of sexual orientation of media partner such person or business, While we encourage readers to support advertisers that make ~ this In:lg,I'I.ine possible, AbOLJ[' 1..•l.ag.1tine 011 not accept responsibility ror advertising since 2012 cl.rims. -

Gobierno De Puerto Rico

GOBIERNO DE PUERTO RICO 18va. Asamblea 5ta. Sesión Legislativa Ordinaria SENADO DE PUERTO RICO P. del S. 1308 30 de mayo de 2019 Presentado por el señor Muñiz Cortés (Por petición de la Legislatura Municipal de Añasco) Referido a la Comisión de Desarrollo del Oeste LEY Para designar con el nombre de Avenida Martha Ivelisse Pesante “Ivy Queen” la Carretera Municipal conocida como “Calle Ancha” del Municipio de Añasco y eximir tal designación de las disposiciones de la Ley Núm. 99 de 22 de junio de 1971, según enmendada, conocida como la “Ley de la Comisión Denominadora de Estructuras y Vías Públicas” y para otros fines. EXPOSICIÓN DE MOTIVOS Es responsabilidad de todos los pueblos el reconocer aquellas figuras que con su ejemplo y compromiso ponen en alto los más grandes valores que les distinguen como ciudadanos. A estos efectos, Martha Ivelisse Pesante, conocida en el mundo artístico como “Ivy Queen” es un ejemplo de superación, dinamismo, humildad y entrega a su pueblo y al género musical que representa. Ivy Queen nació en la población de Añasco pero su vida familiar le llevó a trasladarse de muy joven a Estados Unidos, concretamente a Nueva York. Allí empezó a acercarse a la música escribiendo canciones y participando en algunos concursos. Eran tan sólo los primeros pasos de esta prometedora artista. Unos años después, Ivy Queen decidió regresar a Puerto Rico y fue en la Isla donde, de la mano de DJ Negro, se unió al proyecto “Noise”. Fue esta decisión la que 2 transformó su vida profesional ya que en este colectivo de artistas dedicados al rap fue donde consiguió su primer éxito profesional al componer “Somos raperos pero no delincuentes”. -

Don't Forget to Check out Our Mini Store and Ice Cream Shop Next Door

Most items are cooked to order. Thank you for your patience! LET US HOST YOUR NEXT PARTY HERE AT THE RESTAURANT. KAMAYAN-LUAU STARTING AT $20.00 PER PERSON. *WE CAN HOST 10-50 GUESTS #FUNDRAISINGS #BIRTHDAYS #BARKADA #GETTOGETHER INQUIRE ABOUT OUR CATERINGS #OFFICEPARTIES #CORPORATECATERINGS #ANYEVENTS EMAIL ME AT [email protected] or text at (408) 807-5927 E INQUIRE ABOUT OUR CATERING EVENTS DON’T FORGET TO CHECK OUT OUR MINI STORE AND ICE CREAM SHOP NEXT DOOR ALL OR OUR “TABLE SAUCES” ARE AVAIL FOR SALE AT OUR “SARISARI” STORE. PARTY PACK FROZEN LUMPIAS $29.50 / 4LBS. / 120 PCS. 1POUND PACK FROZEN LUMPIAS $7.95 CHIC OR PORK 1LB. PACK FROZEN TAPA MEAT $8.75 1LB. TAPSILOG MADE LONGANIZA $6.75 ALL AVAILABLE FOR SALE AT OUR “SARISARI’ STORE (GF) = Gluten Free (V) = Available as a Vegetarian Dish ALC = Avalable in ALA Carte portion MSG FREE Prices are all subject to change without notice. ONLY VISA and MasterCards are accepted. For TO-GO menus, please send email request to [email protected], Most items are cooked to order. Thank you for your patience! Now hosting Private Parties, see our Pre-Fixe KAMAYAN/Philippine Luau Menu *OUR MENU ROTATES EVERY 6-8 WEEKS TO KEEP IT INTERESTING Did you know that REDHORSE on tap are not even available in most of the Philippines? AVAILABLE HERE AT TAPSILOG BISTRO!! CRAFT BEERS DESCRIPTION CITY ABV 16oz PITCHER 1/2YARD H-HOUR SAN MIGUEL PALE PHILIPPINE 5.50% $7.00 $20 $5 BEER DRAFT PILSEN ISLANDS $14 RED HORSE DEEPLY PHILIPPINE $7.00 $5 ON TAP HUED ISLANDS 8.0% $20 $14 LAGER / MALT BALLAST -

Andrea's Party Tray Menu Lumpia Pancit & Rice Specialties Chicken

Party Tray Menu 1109 Maple Avenue Vallejo CA | (707) 644-0518 Andrea’s Lumpia Chicken Beef PORK LUMPIA SHANGHAI ...$44/100 pcs ADOBO marinated in vinegar, garlic and soy sauce MECHADO tomato sauce stew with vegetables served with sweet chili sauce AFRITADA tomato sauce with carrots and bell peppers BEEF with fresh button mushrooms BISTEK marinated with lemon, soy sauce and onions FRIED VEGETABLE LUMPIA …$1.00 ea ASADO fried with soy sauce and citrus juice $45 $67 $87 $132 served with spiced vinegar YELLOW CURRY with coconut milk KALDERETA stew with tomato sauce and vegetables FRESH VEGETABLE LUMPIA ...$180/50 pcs mushroom sauce and vegetables potatoes and bell PASTEL , KARE-KARE oxtail, tripe, cheeks in peanut sauce & bagoong served with caramelized sauce with peanuts peppers Pancit & Rice SWEET & SPICY $48 $70 $95 $140 $32 $48 $64 $88 BIHON (rice noodles) OR SOTANGHON-CANTON Seafood CHICKEN With QUAIL EGGS BAKED MUSSELS with parmesan cheese $130/100pcs (vermicelli/egg noodles) $40 $56 $80 $110 SWEET & SOUR WHITE FISH with julienne cut $25 $37 $46 $70 stuffed with chicken meat & vegetables vegetables with sauce PALABOK (thick rice noodles with shrimp) RELLENO ….$45 $41 $62 $80 $110 $28 $41 $54 $75 FRIED DRUMMETTES ...$75/50 pcs SEAFOOD CHOPSUEY with shrimp, squid & mussels STEAMED JASMINE RICE/ GARLIC RICE Pork $12/16 $18/24 $25/35 $36/46 $43 $65 $85 $128 ADOBO marinated in vinegar, garlic and soy sauce RELLENONG BANGUS stuffed milkfish ...$36 FRIED RICE PLAIN/ MEAT OR SHRIMP ASADO -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

Click to Download

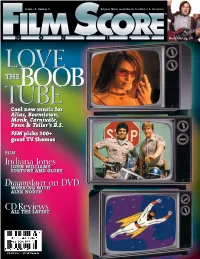

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress.