Imagined Dalmatia: Locality in the Global Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix I Chemistry Syllabi 2011-2012 Academic Year

Appendix I Chemistry Syllabi 2011‐2012 Academic Year Introduction to Chemistry Fall 2011 CHEM1003.1 CRN60090 Dr. Draganjac LSW549 Office LSW542 Lab [email protected] LSW534 Lab 972-3272 Course: 9:00 - 9:50 MWF LSE507 Office hours: 10:00 – 10:50 am MTW; 9:00-10:50 R (Others by appointment) Text: no text Tests: 5 exams (500 points total for the exams). One exam at the end of each of the sections listed below: General Education Science Learning Outcomes/Objectives Objective Description Using Science to Students will be able to understand concepts of science as Accomplish Common they apply to contemporary issues. Goals Section 1. Metric System, Temperature Systems/Conversions, Significant Figures, Unit Conversions, Density, Review of Math, Operation of Electronic Calculators* 2. Chemical Symbols, Atomic Theory, Law of Definite/ Multiple Proportions, Periodic Table**, Writing Formulas, Naming Compounds 3. Stoichiometry, Mole Concept, Percent Composition, Empirical and Molecular Formulas, Writing and Balancing Equations 4. Theoretical yield, Limiting reactants, Solutions, Molarity, Dilutions 5. Gas Laws Course related worksheets Final exam: Friday, December 9, 2011, 8 am. The final will not be comprehensive. Quizzes: 100 points - there will be 15 quizzes (10 points each), the 5 lowest quiz grades will be dropped to give a total of 100 points Total points : 600 Grading - Straight percentage: 90+ A, 80 - 89.9999 B, 70 - 79.9999 C, 60 - 69.9999 D, Below 60 F. Make up exams will be given at the end of the semester. Failure to take the exam at the scheduled time will result in a grade of zero for that exam. -

Prisotnost Zdravstvenih Tem V Stripu Alan Ford Diplomsko Delo

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŢBENE VEDE Pavle Terzič Prisotnost zdravstvenih tem v stripu Alan Ford Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2012 UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŢBENE VEDE Pavle Terzič Mentorica: doc. dr. Tanja Kamin Prisotnost zdravstvenih tem v stripu Alan Ford Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2012 »Torej, mladi moţ, najprej se moraš naučiti osnovni zakon oglasa: Vse mora biti jasno, tako rekoč enostavno, pravzaprav niti malo zapleteno, ampak natančno in izrazito, vsekakor izzivalno, vsiljivo in rahlo skrivnostno, da vsakdo razume vse na prvi pogled. Jasno?« (Secchi in Raviola 1971i, 56) Zahvala doc. dr. Tanji Kamin za mentorstvo in prijetno izkušnjo v času študija, Violeti, vsem otrokom, ki so se rodili v nekih lepših časih. Prisotnost zdravstvenih tem v stripu Alan Ford Diplomsko delo raziskuje narativne vidike mediatizacije zdravstvenih tveganj v stripu kot mediju. Izhaja iz razmišljanja, da imajo mediji pomembno vlogo pri oblikovanju in posredovanju pomenov o zdravju. Na zastavljeno ključno raziskovalno vprašanje, ki je, katera tveganja za zdravje se pojavljajo v stripu Alan Ford, kako pogosto in v kakšnem kontekstu, poskusim odgovoriti s kvalitativnim pristopom k analizi vsebine vseh prvih izdaj stripa Alan Ford, ki so izšli med leti 1970 in 1980. V kontekstu popularne kulture ţelim ugotoviti, ali strip medijske reprezentacije zdravstvenih tveganj utrjuje, dopolnjuje ali problematizira. Raziskava je potrdila, da mediatizirana zdravstvena tveganja v stripu kot mediju in ţanru popularne kulture obstajajo in sledijo nekaterim drugim znanim zvrstem popularnih tekstov, kot so filmi, oglaševalske vsebine, televizijski programi in časopisi. Izpostavljena tveganja za zdravje so: zloraba alkohola, prekomerna telesna teţa in debelost, kajenje, vpliv okoljskih bremen, uporaba prepovedanih drog, tveganja na delovnem mestu, podhranjenost otrok, zvišan krvni sladkor, telesna neaktivnost, povišan krvni tlak in nezadosten vnos sadja in zelenjave. -

1974-75. INSTITUTION Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C.; Linguistic Society of America, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 107 131 FL 006 895 TITLE Guide to Programs in Linguistics: 1974-75. INSTITUTION Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C.; Linguistic Society of America, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 75 NOTE . 235p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$12.05 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *College Language Programs; *College Program;Course Descriptions; Degrees (Titles); Financial Support; Higher Education; Language Instruction; *Linguistics; *Program Descriptions; *Program Guides; Summer Institutes; Uncommonly Taught Languages; Universities ABSTRACT This is a current guide to linguisticsprograms in the United States and Canada. One hundred and sixty-seven institutions are listed which offer fiveor more courses broadly defined as "linguistics" and which also offera degree in linguistics or a degree in another area with a major or minor in linguistics. The institutions' are listed in alphabetical order and under eachentry is given all or part of the following information:name of department, program, etc., and-chairman; a brief description of the program and facilities; course offerings or courseareas; staff; financial support available; academic calendar for 1974-75,;name and address the office from which to obtain brochures, catalogues,etc. Information about annual summer institutes is given in AppendixA. Appendix B is a tabular index of universities and their degree offerings, arranged by state, and Appendix C lists schools which teach at least three courses in linguistics. AppendixD is an index of uncommonly-taught languages indicating which institutionsoffer instruction in them. Appendix E is an index of staff, and AppendixF is an index of linguistis in other departments. (Author/AM) c, Guide toPrograms In Linguistics: E.4.1.1.4 ^EL. -

Nestande Seeks Dismissal of Ex-Supervisor's Libel Suit

-•, Women can sway Searchers zero in on kidnapper vote NOW chief Detectives received more than 1.000 By LISA MAHONEY runn1n1 mate. Gcr1.ld1ne terraro. - ---- Of .. ...,,.. ..... phone calls about abducted HB $Ir! With thlkl na I\ SQ, Women can determine the ou1- "Femro is crca1in1 a d1fli rent 8y ITEVE MARBU: comc of the prts1dcn1i1l race. EJlje lntcrtst level from womeo in this o. ....., ........ S.meal, former ptttident of the NI· cl~lion. It wouldn't be a blllpme For tht first umc llntt li11Je Laura uonal Orpni2.11ion of Women, 1ay1. wnhout her 1n it, .. he aid. Bradbury vani hed ftom her f'amily"t Speaking before I aroup or •bout Smeal, 4S, drew on raearch she deRt't campsite 1 week 110. 17S tludent1 and NOW supponcrs at collected for her book .. Why and How au1.horit1es cxpreaed Opllmiun tl\lt UC Irvine Wednesday night, Smeal Women Will .Elect the Next Presi ~ arep1n1nssround on a man they said the much-discus~ Gellder Gap dent." for her lecture. Women, who bc:hevc abducted the Huntus1i.on -d1ffertnm in the way women and make ul? Sl perctnt of the American Beach11rl. men vote on issues - could upset population, are voting in areatcr four w11neilt$ lold authoritJt'5 President ~ei&an's re-election bid. numbe~ than men: Smeal &aid. And they art convinced they ..-w the S~~I . 1n ~er talk and durina an 12 percent fewer women than men blond·ha1ml 11rt with a bald.to,. &raY· ear her 1nterv1ew, SA.id 1he believes the s1.1pPol1 President Reapn's pohcin, haired man in his SO. -

Plameni Pozdravi, Šestokanalna Video Instalacija (363 Fotografije I Tekstovi Iz Fotografskih Albuma Poslatih Titu Od 1945

ANA ADAMOVIĆ Plameni pozdravi, Šestokanalna video instalacija (363 fotografije i tekstovi iz fotografskih albuma poslatih Titu od 1945. do 1980. godine iz arhiva Muzeja istorije Jugoslavije) 4 5 Ana Adamović Saša Karalić PLAMENI POZDRAVI KVADRAT 13-17 189-190 Dubravka Ugrešić i Ana Adamović Irena Lagator Pejović RAZGOVOR SLOBODA SIGURNOST NAPREDAK 27-34 193-194 Olga Manojlović Pintar Mladen Miljanović ŠEST TEZA O ODRASTANJU LAKOĆA SEĆANJA I TEŽINA ISKUSTVA U SOCIJALISTIČKOJ JUGOSLAVIJI 197 53-62 Škart Radina Vučetić ŠTA PITAŠ KAD NIKO NE PITA? PAJA PATAK S PIONIRSKOM MARAMOM 201 (Socijalističko detinjstvo na američki način) 81-91 Milica Pekić, Branislav Dimitrijević i Stevan Vuković Igor Duda TRANSKRIPT RAZGOVORA DOSTA VELIKI DA NE BUDU MALI održanog 9. aprila 2015. godine 109-111 u okviru izložbe Plameni pozdravi u Muzeju istorije Jugoslavije Nenad Veličković 205-212 ALBUMI, KROKI 125-129 Dejan Kaludjerović i Ana Adamović RAZGOVOR Škart 215-218 pesme iz zbirke ŠTA PITAŠ Renata Poljak i Ana Adamović KAD NIKO NE PITA? RAZGOVOR 141-145 221-225 Martin Pogačar Dušica Dražić i Ana Adamović KRAJ DETINJSTVA: RAZGOVOR šta se dogodilo sa utopijom socijalističkog detinjstva 227-230 i šta u tom pogledu može učiniti nostalgija? 157-164 Maja Pelević i Vuk Pelević CRVENA ZVEZDA OPKOLJENA ZLATOM Ana Hofman 237-243 RASPEVANO SOCIJALISTIČKO DETE? 175-178 Hronologija socijalističke Jugoslavije 244-247 Ildiko Erdei HOR Biografije autora 181-185 249-253 Izložba Plameni pozdravi Muzej istorije Jugoslavije, mart-april 2015. ŠKART ŠTA PITAŠ KAD NIKO NE PITA? (Krevetne pozorišne priče) Izložba Plameni pozdravi Muzej istorije Jugoslavije, mart-april 2015. 13 ANA ADAMOVIC Sredinom 2011. -

DANTE NEWS SOCIETÀ DANTE ALIGHIERI "Il Mondo in Italiano"

DANTE NEWS SOCIETÀ DANTE ALIGHIERI "il mondo in italiano" Newsletter of the Dante Alighieri Society Inc. Brisbane APRILE 2021 DANTE ALIGHIERI SOCIETY 26 Gray Street, New Farm, QLD 4005 Postal address: PO Box 1350 New Farm, QLD 4005 Calendario Phone: 07 3172 3963 Mobile : 0401 927 967 Email: [email protected] Web address: www.dante -alighieri.org.au April 4 – BUONA PASQUA PRESIDENT Claire Kennedy April 19 – Start of TERM 2 [email protected] VICE -PRESIDENTS Rosalia Miglioli April 23 – Conversazioni [email protected] Mario Bono [email protected] April 25 – Cineforum SECRETARY Colleen Hatch [email protected] TREASURER April 29 – Adelaide presents DANTE Kay Martin info@dante -alighieri.com.au EDITOR GUEST EDITORS Bernadine e Rosalia Inside ○ Annual Report ○ Dalla scuola ○ Dalla biblioteca ○ Autobiografia Master chocolatier Fabio Ceraso works on a record-breaking Easter egg dedicated to the 700th anniversary of Dante Alighieri’s death made in a chocolate factory in Na- ples, Italy, on March 20, 2021. (Photo: AAP) https://lafiamma.com.au/en/news/naples-pays-tribute-to-dante-with-giant- easter - egg - 59772/ Pagina 2 SOCIETÀ DANTE ALIGHIERI, BRISBANE aprile 2021 Dante matters President’s report to A.G.M. continues… Cari soci, The prizes for this year’s winners will be presented later this year, on May 28, in conjunction with a It is with much pleasure that I present the celebration of acclaimed author Leonardo Sciascia President’s Report for the year 2020, the 68th year by Tiziana Miceli. Another initiative, ‘Danteatro’, of the Society and my 8th year as President. -

Detroit Aesthetic in Mid-Twentieth-Century Literature Jenna F

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2015 Sex, Labor, And The American Way: Detroit Aesthetic In Mid-Twentieth-Century Literature Jenna F. Gerds Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Recommended Citation Gerds, Jenna F., "Sex, Labor, And The American Way: Detroit Aesthetic In Mid-Twentieth-Century Literature" (2015). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 1131. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. SEX, LABOR, AND THE AMERICAN WAY: DETROIT AESTHETIC IN MID-TWENTIETH-CENTURY LITERATURE by JENNA GERDS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2015 MAJOR: ENGLISH Approved by: __________________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ DEDICATION To Louis and Beatrice. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Endless thanks to my insightful committee members, Drs. Barrett Watten, Renata Wasserman, Jonathan Flatley, and Dora Apel. I would especially like to acknowledge Dr. Barrett Watten’s support and thoughtful feedback, both on this project and throughout the entirety of my graduate education. I would like to thank Miriam Frank and Linda Banks Downs for their insight and will- ingness to meet and talk with a humble graduate student. Thank you to my friends, Mark Brown in particular, for his sage advice. And the warmest expression of gratitude to my family, especially Carl and Roslyn Gerds, who encouraged me throughout this process, Beth Jablonowski, and Cait- lin Gerds Habermas and Phyllis Gerds, without whom my syntax would be increasingly awkward and my voice ever more passive. -

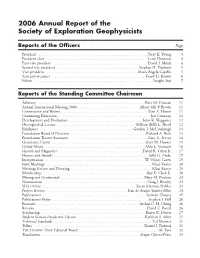

2006 Annual Report of the Society of Exploration Geophysicists

2006 Annual Report of the Society of Exploration Geophysicists Reports of the Officers Page President . .Terry K. Young 3 President-elect . .Leon Thomsen 4 First vice president . .David J. Monk 4 Second vice president . .Stephen H. Danbom 5 Vice president . .María Ángela Capello5 Secretary-treasurer . .Frank D. Brown 6 Editor . .Yonghe Sun 7 Reports of the Standing Committee Chairmen Advisory . .Peter M. Duncan 11 Annual International Meeting 2006 . .Albert (Al) P. Brown 11 Constitution and Bylaws . .Dan A. Ebrom 11 Continuing Education . .Jon Conaway 12 Development and Production . .John R. Waggoner 12 Distinguished Lecture . .William (Bill) L. Abriel 12 Exhibitors . .Gordon J. McCoullough 13 Foundation Board of Directors . .Richard A. Baile 13 Foundation Trustee Associates . .Gary G. Servos 14 Geoscience Center . .Gary M. Hoover 15 Global Affairs . .Aldo L. Vesnaver 16 Gravity and Magnetics . .David R. Oxley Jr. 17 Honors and Awards . .Sally G. Zinke 17 Interpretation . .W. Verney Green 19 Joint Meetings . .Klaas Koster 20 Meetings Review and Planning . .Klaas Koster 20 Membership . .Roy E. Clark Jr. 20 Mining and Geothermal . .Mary M. Poulton 23 Nominations . .Craig J. Beasley 23 SEG Online . .Susan Mastoris Peebler24 Project Review . .Ivan de Araújo Simões-Filho 24 Publications . .Satinder Chopra 25 Publications Policy . .Stephen J. Hill 26 Research . .Arthur C. H. Cheng 26 Reviews . .David C. Bartel 26 Scholarship . .Karen K. Dittert 27 Student Sections/Academic Liaison . .Kathleen J. Aikin 31 Technical Standards . .Ted Mariner 31 Tellers . .Daniel J. Piazzola 31 THE LEADING EDGE Editorial Board . .Ali Tura 32 Translations . .Sergio Chávez-Pérez 33 SEG 2006 Annual Report Reports of the Ad Hoc Committee Chairman Page eGY 2007-2008 . -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Diversity and the European public sphere: the case of the Netherlands van de Beek, J.H.; van de Mortel, S.A.; van Hees, S. Publication date 2010 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): van de Beek, J. H., van de Mortel, S. A., & van Hees, S. (2010). Diversity and the European public sphere: the case of the Netherlands. (Eurosphere country reports; No. 3). Eurosphere. http://eurospheres.org/files/2010/06/Netherlands.pdf General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 EUROSPHERE COUNTRY REPORTS Online Country Report No. 3, 2010 Diversity and the European Public Sphere The Case of the Netherlands Jan H. -

Read #02/2020 ("FOCUS on REGULATION")

LGP Issue 2020 2 // news THE INFO MAGAZINE BY FOCUS ON LANSKY, GANZGER + PARTNER ATTORNEYS-AT-LAW REGULATION TELECOMMUNICATIONS LAW BLOCKCHAIN TECHNOLOGY IoT regulation as a challenge Tokenization as a form of financing DIGITAL SOCIETY STATE AID Telemedicine on a delicate legal footing Prohibition under Union law under the microscope CONTENT Editorial 3 ISSUE 2 // 2020 UP-TO-DATE 4 IoT services as a challenge for telecommunications law 4 The prohibition of state aid – a reminder and an all-clear 8 Digital contract management in practice 10 Is the existing legal framework still able to cope with the increased Telemedicine on a delicate legal footing 12 use of IoT applications in public Employment law and restructuring 14 networks? The coronavirus crisis – prelude to a lived practice of restructuring? 18 Common agricultural policy with ‘green architecture’ 20 12 INTERNATIONAL Tax liability to consider when moving to Austria 22 How safe are telemedical treatments for doctors and Current developments on bilateral investment protection agreements in the EU 24 patients – both in use and in law? From Minister to a successful international lawyer 26 Cross-border enforcement of judgments post-Brexit 28 LGP & Gerstbauer Strategic: dual advisory services with added value 29 32 Nagorno-Karabakh: consequences of a frozen conflict 30 FUTURE TOPICS Especially in times of crisis, it is worthwhile to Tokenisation as a form of financing 32 finance cost-intensive projects by issuing tokens INSIDE Legal updates by LGP Bratislava 34 37 Privy councillors, whisperers and spin doctors 37 ACTIVE In his new book, LGP Senior Expert Illustrious alumni meet at lofty heights 39 Counsel Manfred Matzka describes more than 300 years of éminences Digital finance and alternative investments-Roadshow 39 grises at the Ballhausplatz LANSKY, GANZGER IMPRINT partner Publisher/Media Owner: Lansky, Ganzger & Partner Rechtsanwälte GmbH, Biberstraße 5, A-1010 Wien // Editorial staff: + Dr. -

Reception and Appropriation of Alan Ford Comic Book Series in Yugoslavia

LEIDEN UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Reception and Appropriation of Alan Ford Comic Book Series in Yugoslavia A critical review Jan Charvát 31.08.2020 Student Number: s2575116 Supervisor: Mari Nakamura Programme: International Relations (MA) MA Thesis Culture and Politics 5184VCP01Y Word count: 14314 Acknowledgements I would not be able to study at the Leiden University without the generous support of the Presidium Libertatis scholarship. Therefore, I thank Roger R. Hazewinkel for enabling me to do so and professors Balázs Trencsényi and Jan Hennings for supporting my application. Nanda de Bruin and Hester Bergsma also affiliated with the scholarship both deserve my deep gratitude for their support and care during sometimes uneasy times in Leiden. As for the finished thesis you now have in front of you, the first thank must go to my supervisor Mari Nakamura for her patience and understanding with the COVID-19 related problems that emerged on my side. I am not exaggerating when I say it would not be possible to finish the thesis without her virtues. The second to Filip Bojanić for introducing me to Alan Ford. As having a safe refuge to undergo an ordered quarantine at multiple times throughout the pandemic is a great privilege not many of us have, I thank my parents, who have done all humanly possible and more to give me a home. For providing me with the software and hardware necessary to write the thesis, I thank my brother Ondřej Charvát and Jana Kočková. I would literally get nothing written without them and their help is greatly valued. -

The United States and the World

part 2 The United States and the World 7 Three Flags, 1958. Jasper Johns. Encaustic on canvas, 30 /8 x 45 x 5 in. Fiftieth Anniversary Gift of the Gilman Foundation, Inc., The Lauder Foundation, A. Alfred Taubman, an anonymous donor, and purchase 80.32 “We must be the great arsenal of democracy.” —Franklin D. Roosevelt, radio broadcast, 1940 967 Collection of Whitney Museum of American Art, NY, Photography by Geoffrey Clements, NY 0967 U6P2-845481.indd 967 4/14/06 4:30:33 AM BEFORE YOU READ War Message to Congress MEET FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT ranklin D. Roosevelt was an intensely competitive and social person. His charis- Fmatic demeanor, rich voice, and wide smile expressed confidence and optimism and gave him the power to be very persuasive. In the dark days of the Great Depression and World War II, his buoyant leadership was one of the United Franklin Roosevelt was again active in the States’ greatest assets. Democratic Party and was elected governor of New York. While governor, he gained great popularity by cutting taxes for farmers, reducing the rates charged by public utilities, and giving aid to unemployed “Let me assert my firm belief that New Yorkers. the only thing we have to fear is fear Roosevelt’s popularity paved the way for his presi- itself—” dential win in 1932. Many people in the United States applauded Roosevelt’s use of power to help —Franklin D. Roosevelt people in economic distress. In the first three First Inaugural Address months of his presidency, Congress passed fifteen major acts to provide economic relief to the nation, later known as the First New Deal.