Art. IIL—The PEOPLES of ANCIENT SCOTLAND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY of Macdhubhsith

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY OF MacDHUBHSITH ― MacDUFFIE CLAN (McAfie, McDuffie, MacFie, MacPhee, Duffy, etc.) VOLUME 2 THE LANDS OF OUR FATHERS PART 2 Earle Douglas MacPhee (1894 - 1982) M.M., M.A., M.Educ., LL.D., D.U.C., D.C.L. Emeritus Dean University of British Columbia This 2009 electronic edition Volume 2 is a scan of the 1975 Volume VII. Dr. MacPhee created Volume VII when he added supplemental data and errata to the original 1792 Volume II. This electronic edition has been amended for the errata noted by Dr. MacPhee. - i - THE LIVES OF OUR FATHERS PREFACE TO VOLUME II In Volume I the author has established the surnames of most of our Clan and has proposed the sources of the peculiar name by which our Gaelic compatriots defined us. In this examination we have examined alternate progenitors of the family. Any reader of Scottish history realizes that Highlanders like to move and like to set up small groups of people in which they can become heads of families or chieftains. This was true in Colonsay and there were almost a dozen areas in Scotland where the clansman and his children regard one of these as 'home'. The writer has tried to define the nature of these homes, and to study their growth. It will take some years to organize comparative material and we have indicated in Chapter III the areas which should require research. In Chapter IV the writer has prepared a list of possible chiefs of the clan over a thousand years. The books on our Clan give very little information on these chiefs but the writer has recorded some probable comments on his chiefship. -

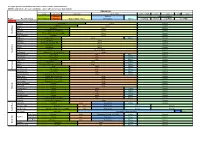

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

Supporting Rural Communities in West Dunbartonshire, Stirling and Clackmannanshire

Supporting Rural Communities in West Dunbartonshire, Stirling and Clackmannanshire A Rural Development Strategy for the Forth Valley and Lomond LEADER area 2015-2020 Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Area covered by FVL 8 3. Summary of the economies of the FVL area 31 4. Strategic context for the FVL LDS 34 5. Strategic Review of 2007-2013 42 6. SWOT 44 7. Link to SOAs and CPPs 49 8. Strategic Objectives 53 9. Co-operation 60 10. Community & Stakeholder Engagement 65 11. Coherence with other sources of funding 70 Appendix 1: List of datazones Appendix 2: Community owned and managed assets Appendix 3: Relevant Strategies and Research Appendix 4: List of Community Action Plans Appendix 5: Forecasting strategic projects of the communities in Loch Lomond & the Trosachs National Park Appendix 6: Key findings from mid-term review of FVL LEADER (2007-2013) Programme Appendix 7: LLTNPA Strategic Themes/Priorities Refer also to ‘Celebrating 100 Projects’ FVL LEADER 2007-2013 Brochure . 2 1. Introduction The Forth Valley and Lomond LEADER area encompasses the rural areas of Stirling, Clackmannanshire and West Dunbartonshire. The area crosses three local authority areas, two Scottish Enterprise regions, two Forestry Commission areas, two Rural Payments and Inspections Divisions, one National Park and one VisitScotland Region. An area criss-crossed with administrative boundaries, the geography crosses these boundaries, with the area stretching from the spectacular Highland mountain scenery around Crianlarich and Tyndrum, across the Highland boundary fault line, with its forests and lochs, down to the more rolling hills of the Ochils, Campsies and the Kilpatrick Hills until it meets the fringes of the urbanised central belt of Clydebank, Stirling and Alloa. -

RULES of PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety

The Fall of Roman Britain RULES OF PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1.0 Introduction ............................2 6.0 Epoch Rounds .........................18 2.0 Sequence of Play ........................6 7.0 Victory ...............................20 3.0 Commands .............................7 8.0 Non-Players ...........................21 4.0 Feats .................................14 Key Terms Index ...........................35 5.0 Events ................................17 Setup and Scenarios.. 37 © 2017 GMT Games LLC • P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232 • www.GMTGames.com 2 Pendragon ~ Rules of Play • 58 Stronghold “castles” (10 red [Forts], 15 light blue [Towns], 15 medium blue [Hillforts], 6 green [Scotti Settlements], 12 black [Saxon Settlements]) (1.4) • Eight Faction round cylinders (2 red, 2 blue, 2 green, 2 black; 1.8, 2.2) • 12 pawns (1 red, 1 blue, 6 white, 4 gray; 1.9, 3.1.1) 1.0 Introduction • A sheet of markers • Four Faction player aid foldouts (3.0. 4.0, 7.0) Pendragon is a board game about the fall of the Roman Diocese • Two Epoch and Battles sheets (2.0, 3.6, 6.0) of Britain, from the first large-scale raids of Irish, Pict, and Saxon raiders to the establishment of successor kingdoms, both • A Non-Player Guidelines Summary and Battle Tactics sheet Celtic and Germanic. It adapts GMT Games’ “COIN Series” (8.1-.4, 8.4.2) game system about asymmetrical conflicts to depict the political, • A Non-Player Event Instructions foldout (8.2.1) military, religious, and economic affairs of 5th Century Britain. -

Annals of the Caledonians, Picts and Scots

Columbia (HnitJer^ftp intlifCttpufUmigdrk LIBRARY COL.COLL. LIBRARY. N.YORK. Annals of t{ie CaleDoiuans. : ; I^col.coll; ^UMl^v iV.YORK OF THE CALEDONIANS, PICTS, AND SCOTS AND OF STRATHCLYDE, CUMBERLAND, GALLOWAY, AND MURRAY. BY JOSEPH RITSON, ESQ. VOLUME THE FIRST. Antiquam exquirite matrem. EDINBURGH PRINTED FOR W. AND D. LAING ; AND PAYNE AND FOSS, PALL-MALL, LONDON. 1828. : r.DiKBURnii FIlINTEn I5Y BAI.LANTTNK ASn COMPAKV, Piiiri.'S WOKK, CANONGATK. CONTENTS. VOL. I. PAGE. Advertisement, 1 Annals of the Caledonians. Introduction, 7 Annals, -. 25 Annals of the Picts. Introduction, 71 Annals, 135 Appendix. No. I. Names and succession of the Pictish kings, .... 254 No. II. Annals of the Cruthens or Irish Picts, 258 /» ('^ v^: n ,^ '"1 v> Another posthumous work of the late Mr Rlt- son is now presented to the world, which the edi- tor trusts will not be found less valuable than the publications preceding it. Lord Hailes professes to commence his interest- ing Annals with the accession of Malcolm III., '* be- cause the History of Scotland, previous to that pe- riod, is involved in obscurity and fable :" the praise of indefatigable industry and research cannot there- fore be justly denied to the compiler of the present volumes, who has extended the supposed limit of authentic history for many centuries, and whose labours, in fact, end where those of his predecessor hegi7i. The editor deems it a conscientious duty to give the authors materials in their original shape, " un- mixed with baser matter ;" which will account for, and, it is hoped, excuse, the trifling repetition and omissions that sometimes occur. -

Cornish Archaeology 41–42 Hendhyscans Kernow 2002–3

© 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society CORNISH ARCHAEOLOGY 41–42 HENDHYSCANS KERNOW 2002–3 EDITORS GRAEME KIRKHAM AND PETER HERRING (Published 2006) CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © COPYRIGHT CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2006 No part of this volume may be reproduced without permission of the Society and the relevant author ISSN 0070 024X Typesetting, printing and binding by Arrowsmith, Bristol © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Contents Preface i HENRIETTA QUINNELL Reflections iii CHARLES THOMAS An Iron Age sword and mirror cist burial from Bryher, Isles of Scilly 1 CHARLES JOHNS Excavation of an Early Christian cemetery at Althea Library, Padstow 80 PRU MANNING and PETER STEAD Journeys to the Rock: archaeological investigations at Tregarrick Farm, Roche 107 DICK COLE and ANDY M JONES Chariots of fire: symbols and motifs on recent Iron Age metalwork finds in Cornwall 144 ANNA TYACKE Cornwall Archaeological Society – Devon Archaeological Society joint symposium 2003: 149 archaeology and the media PETER GATHERCOLE, JANE STANLEY and NICHOLAS THOMAS A medieval cross from Lidwell, Stoke Climsland 161 SAM TURNER Recent work by the Historic Environment Service, Cornwall County Council 165 Recent work in Cornwall by Exeter Archaeology 194 Obituary: R D Penhallurick 198 CHARLES THOMAS © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Preface This double-volume of Cornish Archaeology marks the start of its fifth decade of publication. Your Editors and General Committee considered this milestone an appropriate point to review its presentation and initiate some changes to the style which has served us so well for the last four decades. The genesis of this style, with its hallmark yellow card cover, is described on a following page by our founding Editor, Professor Charles Thomas. -

Kingdom of Strathclyde from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Kingdom of Strathclyde From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Strathclyde (lit. "Strath of the Clyde"), originally Brythonic Ystrad Clud, was one of the early medieval kingdoms of the Kingdom of Strathclyde Celtic people called the Britons in the Hen Ogledd, the Teyrnas Ystrad Clut Brythonic-speaking parts of what is now southern Scotland and northern England. The kingdom developed during the ← 5th century–11th → post-Roman period. It is also known as Alt Clut, the Brythonic century name for Dumbarton Rock, the medieval capital of the region. It may have had its origins with the Damnonii people of Ptolemy's Geographia. The language of Strathclyde, and that of the Britons in surrounding areas under non-native rulership, is known as Cumbric, a dialect or language closely related to Old Welsh. Place-name and archaeological evidence points to some settlement by Norse or Norse–Gaels in the Viking Age, although to a lesser degree than in neighbouring Galloway. A small number of Anglian place-names show some limited settlement by incomers from Northumbria prior to the Norse settlement. Due to the series of language changes in the area, it is not possible to say whether any Goidelic settlement took place before Gaelic was introduced in the High Middle Ages. After the sack of Dumbarton Rock by a Viking army from Dublin in 870, the name Strathclyde comes into use, perhaps reflecting a move of the centre of the kingdom to Govan. In the same period, it was also referred to as Cumbria, and its inhabitants as Cumbrians. During the High Middle Ages, the area was conquered by the Kingdom of Alba, becoming part of The core of Strathclyde is the strath of the River Clyde. -

Critical Dissertations on the Origin, Antiquities, Language, Government

ExLtbkis p. KENNEDY, ANGLESEA-STREET, COLLEGE GREEN, DUBLIN. &^.i.n^ CRITICAL DISSERTATIONS O N T H E ORIGIN, ANTIQUITIES, LANGUAGE, GOVERNMENT, MANNERS, AND RELIGION, O F T H E ANTIENT CALEDONIANS, THEIR POSTERITY THE PICTS, AND THE BRITISH AND IRISH SCOTS. By JOHN MACPHERSON, D. D, Minifler of Slate, in the Isle of Sky. DUBLIN: Printed by Boulter Griersov, Printer to the King's mofl: Excellent Majcfty. mdcclxviii. TO THE HONOURABLE Charles Greville, Efq; De a r Sir, MY Father, who was the Author of the following DifTertations, would not, perhaps, have dedicated them to any man alive. He annexed, and with good reafbn, an idea of fervility to addrefles of this fort, and reckoned them the diigrace of literature. If I could not, from my foul, acquit myfelf of every felfifh view, in prefenting to you the poft- humous works of a father I tenderly loved, you would not have heard from me in this public manner. You know, my dear friend, the fincerity of my affection for you : but even that affedlion fhould not induce me to dedicate to you, had you already arrived at that eminence, in the ftate, which the abilities and fhining a 2 talents DEDICATION. talents of your early youth feem lb largely to promife, left what really is the voice of friendfhip and efteem, fhould be miftaken, by the world, for that of flattery and interefted defigns. I am on the eve of letting out for a very diftant quarter of the world : without afking your permit fion, I leave you this public tefti- mony of my regard for you, not to fecure your future favour, but to ftand as a finall proof of that attach- ment, with which I am, Dear Sir Your moft affedlionate Friend, and moft Obedient Humble Servant, John Macpherjfbn. -

Ancient Dumnonia

ancient Dumnonia. BT THE REV. W. GRESWELL. he question of the geographical limits of Ancient T Dumnonia lies at the bottom of many problems of Somerset archaeology, not the least being the question of the western boundaries of the County itself. Dcmnonia, Dumnonia and Dz^mnonia are variations of the original name, about which we learn much from Professor Rhys.^ Camden, in his Britannia (vol. i), adopts the form Danmonia apparently to suit a derivation of his own from “ Duns,” a hill, “ moina ” or “mwyn,” a mine, w’hich is surely fanciful, and, therefore, to be rejected. This much seems certain that Dumnonia is the original form of Duffneint, the modern Devonia. This is, of course, an extremely respectable pedigree for the Western County, which seems to be unique in perpetuating in its name, and, to a certain extent, in its history, an ancient Celtic king- dom. Such old kingdoms as “ Demetia,” in South Wales, and “Venedocia” (albeit recognisable in Gwynneth), high up the Severn Valley, about which we read in our earliest records, have gone, but “Dumnonia” lives on in beautiful Devon. It also lives on in West Somerset in history, if not in name, if we mistake not. Historically speaking, we may ask where was Dumnonia ? and who were the Dumnonii ? Professor Rhys reminds us (1). Celtic Britain, by G. Rhys, pp. 290-291. — 176 Papers, §*c. that there were two peoples so called, the one in the South West of the Island and the other in the North, ^ resembling one another in one very important particular, vizo, in living in districts adjoining the seas, and, therefore, in being maritime. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87687-2 - Agricola: Tacitus Edited by A . J . Woodman Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE GREEK AND LATIN CLASSICS General Editors P. E. Easterling Regius Professor Emeritus of Greek, University of Cambridge Philip Hardie Senior Research Fellow, Trinity College, and Honorary Professor of Latin, University of Cambridge Richard Hunter Regius Professor of Greek, University of Cambridge E. J. Kenney Kennedy Professor Emeritus of Latin, University of Cambridge S. P. Oakley Kennedy Professor of Latin, University of Cambridge © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87687-2 - Agricola: Tacitus Edited by A . J . Woodman Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87687-2 - Agricola: Tacitus Edited by A . J . Woodman Frontmatter More information TACITUS AGRICOLA edited by A. J. WOODMAN Basil L. Gildersleeve Professor of Classics, University of Virginia with contributions from C. S. KRAUS Thomas A. Thacher Professor of Latin, Yale University © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87687-2 - Agricola: Tacitus Edited by A . J . Woodman Frontmatter More information University Printing House, Cambridge cb2 8bs, United Kingdom Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence. www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521700290 C Cambridge University Press 2014 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

'J.E. Lloyd and His Intellectual Legacy: the Roman Conquest and Its Consequences Reconsidered' : Emyr W. Williams

J.E. Lloyd and his intellectual legacy: the Roman conquest and its consequences reconsidered,1 by E.W. Williams In an earlier article,2 the adequacy of J.E.Lloyd’s analysis of the territories ascribed to the pre-Roman tribes of Wales was considered. It was concluded that his concept of pre- Roman tribal boundaries contained major flaws. A significantly different map of those tribal territories was then presented. Lloyd’s analysis of the course and consequences of the Roman conquest of Wales was also revisited. He viewed Wales as having been conquered but remaining largely as a militarised zone throughout the Roman period. From the 1920s, Lloyd's analysis was taken up and elaborated by Welsh archaeology, then at an early stage of its development. It led to Nash-Williams’s concept of Wales as ‘a great defensive quadrilateral’ centred on the legionary fortresses at Chester and Caerleon. During recent decades whilst Nash-Williams’s perspective has been abandoned by Welsh archaeology, it has been absorbed in an elaborated form into the narrative of Welsh history. As a consequence, whilst Welsh history still sustains a version of Lloyd’s original thesis, the archaeological community is moving in the opposite direction. Present day archaeology regards the subjugation of Wales as having been completed by 78 A.D., with the conquest laying the foundations for a subsequent process of assimilation of the native population into Roman society. By the middle of the 2nd century A.D., that development provided the basis for a major demilitarisation of Wales. My aim in this article is to cast further light on the course of the Roman conquest of Wales and the subsequent process of assimilating the native population into Roman civil society. -

Celtic Britain

1 arfg Fitam ©0 © © © © ©©© © © © © © © 00 « G XT © 8 i imiL ii II I IWtv,-.,, iM » © © © © © ©H HWIW© llk< © © J.Rhjsffi..H. © I EARLY BRITAIN, CELTIC BRITAIN. BY J. RHYS, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon/). Honorary LL.D. (Edin.). Honorary D.Litt. (Wales). FROFESSOR OF CELTIC IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD J PRINCIPAL OF JESUS COLLEGE, AND LATE FELLOW OF MERTON COLLEGE FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY. WITH TWO MAPS, AND WOODCUTS OF COIliS, FOURTH EDITION. FUBLISHED UNDER THE D.RECTION OF THE GENERAL LITERATURE COMMITTEE. LONDON: SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE, NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C. ; 43, queen victoria street, e.c. \ Brighton: 129, north street. New York : EDWIN S. GORHAM. iqoP, HA 1^0 I "l C>9 |X)VE AND MALCOMSON, LIMITED, PRINTERS, 4 AND 5, DEAN STREET, HIGH HOLBORN, LONDON, W.C. PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. These are the days of little books, and when the author was asked to add one to their number, he accepted the invitation with the jaunty simplicity of an inexperienced hand, thinking that it could not give him much trouble to expand or otherwise modify the account given of early Britain in larger works ; but closer acquaintance with them soon convinced him of the folly of such a plan— he had to study the subject for himself or leave it alone. In trying to do the former he probably read enough to have enabled him to write a larger work than this ; but he would be ashamed to confess how long it has occupied him. As a student of language, he is well aware that no severer judgment could be passed on his essay in writing history than that it should be found to be as bad as the etymologies made by historians are wont to be ; but so essential is the study of Celtic names to the elucidation of the early history of Britain that the risk is thought worth incurring.