The Military Representation in the Local Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

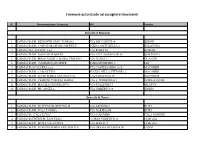

Farmacie Autorizzate Ad Accogliere Tirocinanti

Farmacie autorizzate ad accogliere tirocinanti N° Denominazione Farmacia VIA Località Distretto di Macomer 1 FARMACIA DR. DEMONTIS GIOV. TOMASO VIA DEI CADUTI 14 BIRORI 2 FARMACIA DR. CAPPAI GRAZIANO MICHELE P.ZZA CORTE BELLA 3 BOLOTANA 3 FARMACIA CADEDDU s.a.s. VIA ROMA 56 BORORE 4 FARMACIA DR. BIANCHI ALBERTO VIA VITT. EMANUELE 56 BORTIGALI 5 FARMACIA DR. PIRAS ANGELA MARIA CRISTINA VIA DANTE 1 DUALCHI 6 FARMACIA DR. GAMMINO GIUSEPPE P.ZZA MUNICIPIO 3 LEI 7 FARMACIA SCALARBA s.a.s. VIA CASTELSARDO 12/A MACOMER 8 FARMACIA DR. CABOI LUIGI PIAZZA DELLA VITTORIA 2 MACOMER 9 FARMACIA DR. SECHI MARIA ANTONIETTA VIA SARDEGNA 59 MACOMER 10 FARMACIA DR. CHERCHI TOMASO MARIA VIA E. D'ARBOREA 1 NORAGUGUME 11 FARMACIA DR. MASALA GIANFRANCO VIA STAZIONE 13 SILANUS 12 FARMACIA DR. PIU ANGELA VIA UMBERTO 88 SINDIA Distretto di Nuoro 1 FARMACIA DR. BUFFONI GIUSEPPINA M. VIA ASPRONI 9 BITTI 2 FARMACIA DR. TOLA TONINA VIA GARIBALDI BITTI 3 FARMACIA "CALA LUNA" VIA COLOMBO CALA GONONE 4 FARMACIA EREDI DR. FANCELLO CORSO UMBERTO 13 DORGALI 5 FARMACIA DR. MURA VALENTINA VIA MANNU 1 DORGALI 6 FARMACIA DR. BUFFONI MARIA ANTONIETTA VIA GRAZIA DELEDDA 80 FONNI 7 FARMACIA DR. MEREU CATERINA VIA ROMA 230 GAVOI 8 FARMACIA DR. SEDDA GIANFRANCA LARGO DANTE ALIGHIERI 1 LODINE 9 FARMACIA DR. PIRAS PIETRO VIA G.M.ANGIOJ LULA 10 FARMACIA DR. FARINA FRANCESCO SAVERIO VIA VITT. EMANUELE MAMOIADA 11 FARMACIA SAN FRANCESCO di Luciana Canargiu VIA SENATORE MONNI 2 NUORO 12 FARMACIA DADDI SNC di FRANCESCO DADDI e C. PIAZZA VENETO 3 NUORO 13 FARMACIA DR. -

The Triassic and Jurassic Sedimentary Cycles in Central Sardinia

Geological Field Trips Società Geologica Italiana 2016 Vol. 8 (1.1) ISPRA Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale SERVIZIO GEOLOGICO D’ITALIA Organo Cartografico dello Stato (legge N°68 del 2-2-1960) Dipartimento Difesa del Suolo ISSN: 2038-4947 The Triassic and Jurassic sedimentary cycles in Central Sardinia: stratigraphy, depositional environment and relationship between tectonics and sedimentation 85° Congresso Nazionale della Società Geologica Italiana - Sassari, 2008 DOI: 10.3301/GFT.2016.01 The Triassic and Jurassic sedimentary cycles in Central Sardinia: stratigraphy, depositional environment and relationship between tectonics and sedimentation L. G. Costamagna - S. Barca GFT - Geological Field Trips geological fieldtrips2016-8(1.1) Periodico semestrale del Servizio Geologico d'Italia - ISPRA e della Società Geologica Italiana Geol.F.Trips, Vol.8 No.1.1 (2016), 78 pp., 54 figs. (DOI 10.3301/GFT.2016.01) The Triassic and Jurassic sedimentary cycles in Central Sardinia: stratigraphy, depositional environment and relationship between tectonics and sedimentation 85° Congresso Nazionale della Società Geologica Italiana, Sassari 6-8 settembre 2010 Luca G. Costamagna*, Sebastiano Barca** * Dipartimento di Scienze Chimiche e Geologiche, Via Trentino, 51 - 09127, Cagliari (Italy) ** Via P. Sarpi, 18 - 09131, Cagliari (Italy) Corresponding Author e-mail address: [email protected] Responsible Director Claudio Campobasso (ISPRA-Roma) Editorial Board Editor in Chief Gloria Ciarapica (SGI-Perugia) M. Balini, G. Barrocu, C. Bartolini, 2 Editorial Responsible D. Bernoulli, F. Calamita, B. Capaccioni, Maria Letizia Pampaloni (ISPRA-Roma) W. Cavazza, F.L. Chiocci, R. Compagnoni, D. Cosentino, Technical Editor S. Critelli, G.V. Dal Piaz, C. D'Ambrogi, Mauro Roma (ISPRA-Roma) P. -

Official Journal C 3 of the European Union

Official Journal C 3 of the European Union Volume 62 English edition Information and Notices 7 January 2019 Contents IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2019/C 3/01 Euro exchange rates .............................................................................................................. 1 NOTICES FROM MEMBER STATES 2019/C 3/02 Notice inviting proposals for the transfer of an extraction area for hydrocarbon extraction ................ 2 2019/C 3/03 Communication from the Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Policy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands pursuant to Article 3(2) of Directive 94/22/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the conditions for granting and using authorisations for the prospection, exploration and production of hydrocarbons ................................................................................................... 4 V Announcements PROCEDURES RELATING TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF COMPETITION POLICY European Commission 2019/C 3/04 Prior notification of a concentration (Case M.9148 — Univar/Nexeo) — Candidate case for simplified procedure (1) ........................................................................................................................ 6 EN (1) Text with EEA relevance. OTHER ACTS European Commission 2019/C 3/05 Publication of the amended single document following the approval of a minor amendment pursuant to the second subparagraph of Article 53(2) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 ............................. -

PANE FRESCO” Legge Regionale 21 Marzo 2016, N

Direzione Generale Servizio Gestione Offerta del Territorio ELENCO OPERATORI CONTRASSEGNO “PANE FRESCO” Legge regionale 21 marzo 2016, n. 4 Disposizioni in materia di tutela della panificazione e delle tipologie da forno tipiche della Sardegna Allegato alla Determinazione del Servizio gestione offerta del territorio PROT. N.16010 REP. N.1281 del 12/11/2018 N° Nome Cognome Prov. Titolare del Panificio Indirizzo Località REA 1 Angela M. Antonietta Piras OR Panificio di Piras Angelo e C. Via Palmas, 90 Oristano 106501 2 Stefano Secci NU Via Ospitone, 107 Seulo 82240 3 Michael Lai NU Panificio Lai snc di Lai Michael Zona P.I.P: Iriai Lotto n. 19 Dorgali 87146 3 Francesca Agus CA Su Civraxiu Loc. Camisa Castiadas 198673 Panificio di Antonio Piras di Marcello e 4 Marcello Piras OR Claudia Piras Via Marconi, 18 Guspini 239198 5 Alessia Maria Demurtas NU Pan-Dem Via E. D’arborea, 7 Villagrande Strisaili 61179 6 Gianfranco Porta CA Panificio Porta Zona artigianale Lotto 27 Gonnosfanadiga 118374 7 Franca Angela Contu OG Via Roma, 32 Ilbono 105292 8 Valentino Stochino NU Panificio Stochino Valentino Via Sardegna Arzana 90480 9 Giovanni Cossu NU Panificio Cossu 1963 Via Piemonte Austis 100632 10 Maria Antonietta Zedde NU Panificio S’Argalasi Via Carlo Alberto, 5 Austis 85125 11 Gisella Lilliu NU Panificio Lilliu Gisella Via Leopardi Barisardo 51150 12 Sandro Antonello Fadda NU Panificio Fadda Sandro Antonello Via Nuova Birori 101285 13 Giulio Cossellu NU Panificio Cossellu SNC Via Pascoli,8 Bitti 44579 14 Nicolino Cannas NU Arte Bianca Snc Via Sardegna, 4 Bortigali 101220 15 Adriano Chelo OR Panificio Chelo Adriano Via Franzina, 2 Bosa 85209 16 Gian Luca Frontello OR Sa Pintadera di Fronte Via C. -

Military Landscapes Military Landscapes

a cura di l edited by Donatella Rita Fiorino ATTI DEL CONVEGNO INTERNAZIONALE Scenari per il futuro del patrimonio militare PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE A future for military heritage MILITARY LANDSCAPES MILITARY LANDSCAPES ATTI DEL CONVEGNO INTERNAZIONALE Scenari per il futuro del patrimonio militare PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE A future for military heritage a cura di | edited by Donatella Rita Fiorino Quest’opera è stata rilasciata con licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 3.0 Italia. Per leggere una copia della licenza visita il sito web http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/it/ o spedisci una lettera a Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. CC 2017 MiBACT - Polo Museale della Sardegna CC 2017 DICAAR - Università degli Studi di Cagliari CC 2017 Skira editore, Milano Prima edizione digitale, dicembre 2017 First digital edition, December 2017 ISBN: 978-88-572-3732-9 www.skira.net MILITARY LANDSCAPES SCENARI PER IL FUTURO DEL PATRIMONIO MILITARE Un confronto internazionale in occasione del 150° anniversario della dismissione delle piazzeforti militari in Italia A FUTURE FOR MILITARY HERITAGE An international overview event celebrating the 150th anniversary -

The Case of Sardinia

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Biagi, Bianca; Faggian, Alessandra Conference Paper The effect of Tourism on the House Market: the case of Sardinia 44th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regions and Fiscal Federalism", 25th - 29th August 2004, Porto, Portugal Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Biagi, Bianca; Faggian, Alessandra (2004) : The effect of Tourism on the House Market: the case of Sardinia, 44th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regions and Fiscal Federalism", 25th - 29th August 2004, Porto, Portugal, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/116951 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Perdasdefogu, Pro Loco, Fondazione Di Sardegna

COMUNE DI NUORO COMUNE DI ORISTANO COMUNE DI LANUSEI COMUNE DI CARBONIA COMUNE DI OZIERI COMUNE DI BAUNEI Il ritorno a Torino - SUPERFESTIVAL Salone del libro: venerdì 10 maggio col Comune di Perdasdefogu, Pro Loco, Fondazione di Sardegna La Sapienza di Roma SISTEMA BIBLIOTECARIO OGLIASTRA In collaborazione con: Ambasciata della Colombia in Italia Comuni di Cagliari, Carbonia, Lanusei, Nuoro, Oristano, Guasila, Villamassargia, Perdasdefogu, Università di Malaga, Urbino, La Sapienza di Roma Associazioni Pro loco di Lanusei, Baunei, Sistema bibliotecario Ogliastra e Istituzione San Michele di Ozieri Nona edizione Dove dormire: 2019 Hotel Su Tetioni 3382725132 B&B Santa Barbara tel 3383551700 B&B Signorida tel. 3291248598 Belvedere tel. 3280154733 Dove mangiare: La lanterna nel bosco tel. 3382725132 La ruota tel. 078294683 Civico 10 tel. 0782950016 Perdasdefogu Da Micio tel. 3472775978 Pro Loco Via IV novembre 15 29 luglio - 4 agosto telefono 0782-94292 - 0782 221732 (3392259073) COMUNE DI PRO LOCO PERDASDEFOGU PERDASDEFOGU Programma 7 SERE 7 PIAZZE 7 LIBRI NELLA TOP 50 DELL’UNIVERSITÀ Prefestival in Ogliastra e Logudoro Giovedì 1 agosto LA SAPIENZA DI ROMA con Dacia Maraini e Paolo Cornaglia Piazza Europa Ferraris - 8-19-20-21 luglio “Il silenzio e il mare” di Asmae Dachan. Con l’autrice dialogano Laura Silvia Battaglia e Domenica 28 luglio Ore 19 Paola Piras. Musica di Vanni Masala. ore 19 - Sfilata dei gruppi folk di Romania, Ecuador, Bolivia, Kazakistan, Gruppo Antonia Mesina di Venerdì 2 agosto Orgosolo, “Santa Barbara” di Gadoni, “Silvana Scalinata Sa Muragessa Coni” di Perdasdefogu. “Animali come noi” di Monica Pais. Con l’autrice ore 22 - Esibizione degli stessi gruppi nella Piazza dialoga Sara Marceddu. -

Il Paes Del Comune Di Perdasdefogu

IL PAES DEL COMUNE DI PERDASDEFOGU ENERGIA NOA SRL Società di servizi per l’ingegneria Sommario 1. INTRODUZIONE .................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Il patto dei sindaci........................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 PAES ............................................................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Impegno del Comune ...................................................................................................................... 6 1.4 Riferimento Nazionale ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.5 Riferimento Regionale ..................................................................................................................... 7 1.5.1 Piano Energetico Ambientale Regionale (PEAR) ............................................................................ 7 1.5.2 Obiettivi del PEAR ....................................................................................................................11 1.6 Coinvolgimento di cittadini e stakeholder .........................................................................................14 1.7 Struttura organizzativa per la creazione del PAES...............................................................................14 1.8 Metodologia di lavoro ....................................................................................................................15 -

Phylogenetic Relationships of Sardinian Cave Salamanders, Genus Hydromantes, Based on Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Sequence Data

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 51 (2009) 399–404 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Short Communication Phylogenetic relationships of Sardinian cave salamanders, genus Hydromantes, based on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequence data Arie van der Meijden a,*, Ylenia Chiari b,1, Mauro Mucedda c, Salvador Carranza d, Claudia Corti e, Michael Veith a a Department of Biogeography, University of Trier, Am Wissenschaftspark 25-27, 54296 Trier, Germany b Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, YIBS-Molecular Systematics and Conservation Genetics Lab, ESC 158, Yale University, 21 Sachem St., New Haven, CT 06520-8105, USA c Via Leopardi 1, Sassari, Gruppo Speleologico Sassarese, Italy d Institute of Evolutionary Biology (UPF-CSIC), Passeig Maritim de la Barceloneta 37-49, E-08003 Barcelona, Spain e Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università di Firenze, Sezione di Zoologia ‘‘La Specola”, Via Romana, 17, 50125 Firenze, Italy article info Article history: Received 5 September 2008 Ó 2009 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Revised 12 November 2008 Accepted 10 December 2008 Available online 24 December 2008 1. Introduction by five species, versus only three species in mainland Europe, and three in the western USA. Recently, Vieites et al. (2007) have The Tyrrhenian island of Sardinia is known for its high level of brought forward a compelling hypothesis for the highly disjunct endemism (Oosterbroek and Arntzen, 1992; Grill et al., 2007). distribution of the members of the genus Hydromantes between Beside the importance of this island as a refuge during the last gla- the western US and Europe by suggesting dispersal through the ciations, little is known about the origin and relationships of Sardi- Bering land bridge. -

Tabelle Viciniorità

SISTEMA INFORMATIVO DEL MINISTERO DELLA PUBBLICA ISTRUZIONE PROVINCIA DI: NUORO TABELLA DI VICINIORITA' COMUNE ARITZO 1 BELVI 2 GADONI 3 TONARA 4 DESULO 5 ATZARA 6 MEANA SARDO 7 SORGONO 8 TIANA 9 LACONI 10 SEULO 11 OVODDA 12 TETI 13 AUSTIS 14 VILLANOVATULOO 15 NURALLAO 16 SADALI 17 GENONI 18 NURAGUS 19 ORTUERI 20 FONNI 21 GAVOI 22 LODINE 23 ISILI 24 OLZAI 25 SEUI 26 NURRI 27 OLLOLAI 28 ESTERZILI 29 ORROLI 30 SERRI 31 ESCOLCA 32 MAMOIADA 33 SARULE 34 GERGEI 35 OTTANA 36 ORANI 37 USSASSAI 38 ONIFERI 39 ORGOSOLO 40 ESCALAPLANO 41 NUORO 42 NORAGUGUME 43 OROTELLI 44 BOLOTANA 45 BORORE 46 DUALCHI 47 LEI 48 GAIRO 49 SILANUS 50 MACOMER 51 OSINI 52 BIRORI 53 OLIENA 54 VILLAGRANDE STRISAILI 55 ULASSAI 56 BORTIGALI 57 JERZU 58 PERDASDEFOGU 59 ARZANA 60 LANUSEI 61 CARDEDU 62 ILBONO 63 SINDIA 64 ELINI 65 ORUNE 66 LOCERI 67 TERTENIA 68 SUNI 69 DORGALI 70 GALTELLI 71 BARI SARDO 72 FLUSSIO 73 TINNURA 74 MODOLO 75 BITTI 76 MAGOMADAS 77 LULA 78 ONIFAI 79 SAGAMA 80 BOSA 81 TORTOLI' 82 IRGOLI 83 GIRASOLE 84 LOCULI 85 OROSEI 86 LOTZORAI 87 ONANI 88 SINISCOLA 89 MONTRESTA 90 BAUNEI 91 OSIDDA 92 POSADA 93 TRIEI 94 TORPE' 95 URZULEI 96 TALANA 97 LODE' 98 BUDONI 99 SAN TEODORO SISTEMA INFORMATIVO DEL MINISTERO DELLA PUBBLICA ISTRUZIONE PROVINCIA DI: NUORO TABELLA DI VICINIORITA' COMUNE ARZANA 1 ELINI 2 ILBONO 3 LANUSEI 4 VILLAGRANDE STRISAILI 5 LOCERI 6 GAIRO 7 OSINI 8 TORTOLI' 9 GIRASOLE 10 BARI SARDO 11 LOTZORAI 12 ULASSAI 13 CARDEDU 14 JERZU 15 BAUNEI 16 USSASSAI 17 TRIEI 18 TERTENIA 19 TALANA 20 PERDASDEFOGU 21 SEUI 22 FONNI 23 URZULEI 24 MAMOIADA 25 SADALI -

Dinamiche E Tendenze Dello Spopolamento in Sardegna”

Dinamiche e tendenze dello spopolamento in Sardegna Focus sulle aree LEADER Un aggiornamento funzionale alle politiche di sviluppo rurale dell’Autorità di Gestione del Programma di Sviluppo Rurale della Regione Sardegna 2 Dinamiche e tendenze dello spopolamento in Sardegna Focus sulle aree LEADER Un aggiornamento funzionale alle politiche di sviluppo rurale dell’Autorità di Gestione del Programma di Sviluppo Rurale della Regione Sardegna 3 Documento realizzato nell’ambito delle attività della Rete Rurale Nazionale - Postazione Regione Sardegna, in collaborazione con la Direzione Generale dell’Assessorato dell’Agricoltura e Riforma Agro-Pastorale della Regione Autonoma della Sardegna – Autorità di Gestione del Programma di Sviluppo Rurale 2007-2013. Redazione: Valentina Carta –Rete Rurale Nazionale, postazione della Regione Sardegna Enrico Lobina – Funzionario dell’Assessorato dell’Agricoltura e Riforma Agro-Pastorale Fabio Muscas – Rete Rurale Nazionale, postazione della Regione Sardegna Elaborazione dati e tabelle: Valentina Carta – Rete Rurale Nazionale, postazione della Regione Sardegna Cartografia: Fabio Muscas – Rete Rurale Nazionale, postazione della Regione Sardegna Hanno collaborato: Prof. Giuseppe Puggioni, docente di statistica presso l’Università degli studi di Cagliari, per la metodologia di calcolo degli indicatori. Lo Staff della Direzione Generale dell’Assessorato dell’Agricoltura e Riforma Agro-Pastorale della Regione Autonoma della Sardegna. 4 Indice Presentazione ................................................................................................................ -

COMUNE DI PERDASDEFOGU Provincia Dell’Ogliastra Servizio Di Protezione Civile

COMUNE DI PERDASDEFOGU Provincia dell’Ogliastra Servizio di Protezione Civile Piano Comunale di Protezione Civile Relazione generale Aggiornato a ottobre 2016 Dott. ZAIA Danilo Ancitel Sardegna S.r.l. ____________________________________ Comune di Perdasdefogu (OG) – Piano di Protezione Civile, Relazione Generale _____________________________________ Pag. 2 Sommario 0 Allegati ................................................................................................................ 4 1 Introduzione ....................................................................................................... 5 2 Il territorio di Perdasdefogu ................................................................................ 7 3 Validità del piano .............................................................................................. 15 3.1 Tempi di aggiornamento .......................................................................................................... 15 4 Informazione alla popolazione .......................................................................... 16 5 Valutazione dei rischi ........................................................................................ 18 6 Rischio incendi di interfaccia ............................................................................. 20 6.1 Pericolosità incendi .................................................................................................................. 21 6.2 Vulnerabilità incendi ...............................................................................................................