Phylogenetic Relationships of Sardinian Cave Salamanders, Genus Hydromantes, Based on Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Sequence Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

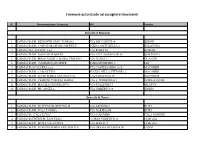

Farmacie Autorizzate Ad Accogliere Tirocinanti

Farmacie autorizzate ad accogliere tirocinanti N° Denominazione Farmacia VIA Località Distretto di Macomer 1 FARMACIA DR. DEMONTIS GIOV. TOMASO VIA DEI CADUTI 14 BIRORI 2 FARMACIA DR. CAPPAI GRAZIANO MICHELE P.ZZA CORTE BELLA 3 BOLOTANA 3 FARMACIA CADEDDU s.a.s. VIA ROMA 56 BORORE 4 FARMACIA DR. BIANCHI ALBERTO VIA VITT. EMANUELE 56 BORTIGALI 5 FARMACIA DR. PIRAS ANGELA MARIA CRISTINA VIA DANTE 1 DUALCHI 6 FARMACIA DR. GAMMINO GIUSEPPE P.ZZA MUNICIPIO 3 LEI 7 FARMACIA SCALARBA s.a.s. VIA CASTELSARDO 12/A MACOMER 8 FARMACIA DR. CABOI LUIGI PIAZZA DELLA VITTORIA 2 MACOMER 9 FARMACIA DR. SECHI MARIA ANTONIETTA VIA SARDEGNA 59 MACOMER 10 FARMACIA DR. CHERCHI TOMASO MARIA VIA E. D'ARBOREA 1 NORAGUGUME 11 FARMACIA DR. MASALA GIANFRANCO VIA STAZIONE 13 SILANUS 12 FARMACIA DR. PIU ANGELA VIA UMBERTO 88 SINDIA Distretto di Nuoro 1 FARMACIA DR. BUFFONI GIUSEPPINA M. VIA ASPRONI 9 BITTI 2 FARMACIA DR. TOLA TONINA VIA GARIBALDI BITTI 3 FARMACIA "CALA LUNA" VIA COLOMBO CALA GONONE 4 FARMACIA EREDI DR. FANCELLO CORSO UMBERTO 13 DORGALI 5 FARMACIA DR. MURA VALENTINA VIA MANNU 1 DORGALI 6 FARMACIA DR. BUFFONI MARIA ANTONIETTA VIA GRAZIA DELEDDA 80 FONNI 7 FARMACIA DR. MEREU CATERINA VIA ROMA 230 GAVOI 8 FARMACIA DR. SEDDA GIANFRANCA LARGO DANTE ALIGHIERI 1 LODINE 9 FARMACIA DR. PIRAS PIETRO VIA G.M.ANGIOJ LULA 10 FARMACIA DR. FARINA FRANCESCO SAVERIO VIA VITT. EMANUELE MAMOIADA 11 FARMACIA SAN FRANCESCO di Luciana Canargiu VIA SENATORE MONNI 2 NUORO 12 FARMACIA DADDI SNC di FRANCESCO DADDI e C. PIAZZA VENETO 3 NUORO 13 FARMACIA DR. -

Ossa Valeria 12/07/77 Cagliari Monserrato Ca 38,10

CORSO PER OPERATORE SOCIO-SANITARIO - QUALIFICAZIONE Lotto n° 5 AZIONE B CA Selezione candidati GRADUATORIA AMMESSI AGENZIA FORMATIVA_CPE LEONARDO PUNTE POSIZIONE Provincia di GGIO Nominativo DATA DI NASCITA LUOGO DI NASCITA COMUNE DI RESIDENZA Residenza ( GRADUATORIA sigla) COMPL ESSIVO 1 MURRU M.ASSUNTA 15/08/56 MURAVERA MURAVERA CA 90,00 2 MURA BIANCA 13/08/62 CAGLIARI CAGLIARI CA 90,00 3 VIRDIS SERENELLA 14/10/64 DECIMOMANNU ASSEMINI CA 90,00 4 SERRAU TIZIANA 30/09/66 USSASSAI CAPOTERRA CA 90,00 5 LISAI ORNELLA 27/04/61 CARBONIA SELARGIUS CA 86,50 6 PORCEDDU IGNAZIA 25/01/52 MANDAS MANDAS CA 85,00 7 PIRASTRU ROBERTINO 21/10/65 SILIQUA SILIQUA CA 85,00 8 MURGIA KATY 08/08/68 CAGLIARI MURAVERA CA 85,00 9 MATTA LUCIANO 15/12/62 MANDAS MANDAS CA 84,50 10 PICCONI RAIMONDA 05/11/50 SEULO NURAMINIS CA 80,00 11 SANSEVIERI ANTONIA 10/11/56 EBOLI MURAVERA CA 80,00 12 PUDDU PAOLA 22/03/58 CAGLIARI CAGLIARI CA 80,00 13 CORONA IGNAZIO 15/08/59 CAGLIARI SINNAI CA 80,00 14 FLORE LUCIA 08/01/61 BUDONI QUARTU SANT'ELENA CA 80,00 15 ZUCCA PAOLA 01/12/62 SERRAMANNA VILLASOR CA 80,00 16 TIDU ANTONIO 26/06/64 DECIMOMANNU DECIMOMANNU CA 80,00 17 MARONGIU ANNA MARIA 01/03/66 VILLASPECIOSA DECIMOMANNU CA 80,00 18 GASTALDI SUSANNA 01/01/67 CAGLIARI DOLIANOVA CA 80,00 19 TUVERI MARCO 24/01/70 DECIMOMANNU ASSEMINI CA 80,00 20 MANCA VALERIA 18/05/74 CAGLIARI SINNAI CA 80,00 21 GARAU EMILIO 25/11/66 CAGLIARI ASSEMINI CA 74,70 22 ORRU ADELINA 03/05/63 NURRI NURRI CA 72,90 23 BINI ISABELLA 01/03/76 CAGLIARI CAGLIARI CA 72,10 24 CORDA SANDRINO 07/11/1965 ASSEMINI -

Libro Soci GAL Barbagia Aggiornato Al 25/06/2020 SOCI PRIVATI N. Cognome Nome Denominazione Sede Legale Comune 1 Garippa Andrea

Libro soci GAL Barbagia aggiornato al 25/06/2020 SOCI PRIVATI Sede legale n. Cognome Nome Denominazione Comune 1 Garippa Andrea Arte bianca Sas di Garippa Andrea Orgosolo 2 Angioi Stefano Gesuino Orotelli 3 Arbau Efisio Sapores srls Orotelli Managos minicaseificio artigianale di 4 Baragliu Maria Vittoria Baragliu Maria Vittoria Orotelli 5 Bosu Tonino Società Cooperativa Aeddos Orotelli 6 Brau Antonello Azienda agricola Brau Antonello Orotelli Impresa artigianale Pasticceria 7 Cardenia Francesco Cardenia Mamoiada Gian. E Assu.& C. snc di Gianfranco 8 Crissantu Gianfranco Crissantu Orgosolo 9 Golosio Francesco Agronomo Nuoro Società Agricola Eredi Golosio Gonario 10 Golosio Mario s.s. Nuoro 11 Cardenia Francesco Associazione Culturale Atzeni Mamoiada Associazione Culturale Folkloristica 12 Ledda Davide Gruppo Folk Orotelli Orotelli 13 Lunesu Cosima Azienda agricola Lunesu Cosima Orotelli 14 Marteddu Giovannino Fondazione Salvatore Cambosu Orotelli 15 Melis Mariantonietta Mamoiada 16 Morette Emanuele Orotelli GAL BARBAGIA (Gruppo Azione Locale Barbagia) - Zona Industriale PIP loc Mussinzua 08020 Orotelli (NU) – CF 93054090910 www.galbarbagia.it email [email protected] 17 Moro Mattia Azienda agricola Moro Mattia Mamoiada 18 Nieddu Giovanni Orotelli 19 Nieddu Cinzia Associazione Culturale Sa Filonzana Ottana 20 Paffi Mario Società Cooperativa Viseras Mamoiada 21 Pira Francesco Cantine di Orgosolo srl Orgosolo 22 Santoni Fabrizio Orotelli 23 Sedda Pasquale Mamoiada 24 Sini Francesco Mamoiada 25 Zoroddu Antonia Orotelli 26 Zoroddu Marialfonsa -

Graduatoria Valida Per Per Avviamento a Selezione Presso L'agenzia Delle Entrate, Sedi Di Nuoro E Lanusei Di N

SERVIZIO POLITICHE A FAVORE DI SOGGETTI A RISCHIO DI ESCLUSIONE CENTRO PER L'IMPIEGO DI NUORO Graduatoria valida per per avviamento a selezione presso l'Agenzia delle Entrate, sedi di Nuoro e Lanusei di n. 2 persone con disabilità da inquadrare nel profilo professionale di operatore – 2^ Area funzionale, fascia retributiva F1 riservato alle persone con disabilità di cui all’art. 1 della legge 12 marzo 1999, n. 68, iscritte negli elenchi del collocamento obbligatorio Posizione CPI Identificativo univoco Riserva Punteggio 1 NUORO 2017NU0009813 824,00 2 NUORO 2017NU0009731 828,00 3 NUORO 2017NU0009753 840,00 4 NUORO 2017NU0009757 852,00 5 LANUSEI 2017NU0009852 852,00 6 NUORO 2017NU0009744 852,00 7 NUORO 2017NU0009989 852,00 8 LANUSEI 2017NU0009958 853,00 9 NUORO 2017NU0009817 854,00 10 NUORO 2017NU0009733 854,00 11 SORGONO 2017NU0009784 856,00 12 NUORO 2017NU0009842 858,00 13 NUORO 2017NU0009766 860,00 14 LANUSEI 2017NU0009974 * 860,00 15 NUORO 2017NU0009880 860,00 16 NUORO 2017NU0009799 860,00 17 NUORO 2017NU0009747 860,00 18 SINISCOLA 2017NU0009891 860,00 19 LANUSEI 2017NU0009832 860,00 20 MACOMER 2017NU0009879 860,00 21 SORGONO 2017NU0009812 864,00 22 SORGONO 2017NU0009921 864,00 23 MACOMER 2017NU0009820 864,00 24 LANUSEI 2017NU0009859 * 864,00 25 SORGONO 2017NU0009745 864,00 26 NUORO 2017NU0009814 866,00 27 LANUSEI 2017NU0009959 867,00 28 NUORO 2017NU0009748 868,50 29 NUORO 2017NU0009810 868,50 30 NUORO 2017NU0009728 868,50 31 SORGONO 2017NU0009916 870,00 32 NUORO 2017NU0009897 870,50 33 NUORO 2017NU0009800 872,50 34 NUORO 2017NU0009777 -

The Triassic and Jurassic Sedimentary Cycles in Central Sardinia

Geological Field Trips Società Geologica Italiana 2016 Vol. 8 (1.1) ISPRA Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale SERVIZIO GEOLOGICO D’ITALIA Organo Cartografico dello Stato (legge N°68 del 2-2-1960) Dipartimento Difesa del Suolo ISSN: 2038-4947 The Triassic and Jurassic sedimentary cycles in Central Sardinia: stratigraphy, depositional environment and relationship between tectonics and sedimentation 85° Congresso Nazionale della Società Geologica Italiana - Sassari, 2008 DOI: 10.3301/GFT.2016.01 The Triassic and Jurassic sedimentary cycles in Central Sardinia: stratigraphy, depositional environment and relationship between tectonics and sedimentation L. G. Costamagna - S. Barca GFT - Geological Field Trips geological fieldtrips2016-8(1.1) Periodico semestrale del Servizio Geologico d'Italia - ISPRA e della Società Geologica Italiana Geol.F.Trips, Vol.8 No.1.1 (2016), 78 pp., 54 figs. (DOI 10.3301/GFT.2016.01) The Triassic and Jurassic sedimentary cycles in Central Sardinia: stratigraphy, depositional environment and relationship between tectonics and sedimentation 85° Congresso Nazionale della Società Geologica Italiana, Sassari 6-8 settembre 2010 Luca G. Costamagna*, Sebastiano Barca** * Dipartimento di Scienze Chimiche e Geologiche, Via Trentino, 51 - 09127, Cagliari (Italy) ** Via P. Sarpi, 18 - 09131, Cagliari (Italy) Corresponding Author e-mail address: [email protected] Responsible Director Claudio Campobasso (ISPRA-Roma) Editorial Board Editor in Chief Gloria Ciarapica (SGI-Perugia) M. Balini, G. Barrocu, C. Bartolini, 2 Editorial Responsible D. Bernoulli, F. Calamita, B. Capaccioni, Maria Letizia Pampaloni (ISPRA-Roma) W. Cavazza, F.L. Chiocci, R. Compagnoni, D. Cosentino, Technical Editor S. Critelli, G.V. Dal Piaz, C. D'Ambrogi, Mauro Roma (ISPRA-Roma) P. -

COMUNE Di DUALCHI Provincia Di Nuoro Via Parini N° 1 C.A.P

COMUNE di DUALCHI Provincia di Nuoro Via Parini n° 1 c.a.p. 08010 __________________________________________________________________________________________ http://www.comune.dualchi.gov.it Tel. n° 0785.44723 & Fax. n° 0785.44902 e-mail: [email protected] CF e P.Iva 00155030919 AREA TECNICA AVVISO di APPALTO AGGIUDICATO Ai sensi dell’articolo 65 e 122 del D.Lgs. n° 163 del 12.04.2006 (Allegato IXA) dell’articolo 22 della L.R. n° 5 del 07.08.2007 dell’articolo 110 del D.P.R. n° 207 del 05.10.2010 Protocollo n° 132 del 12 Gennaio 2015 Stazione appaltante: Ufficio Tecnico del Comune di Dualchi, sito a Dualchi in via Parini n° 01 - C.a.p. 08010 in Provincia di Nuoro, Tel. n° 0785.44723 & Fax. n° 0785.44902, e.mail [email protected] , indirizzo internet http://www.comune.dualchi.gov.it , ed e.mail certificata [email protected]. Procedura di gara: Negoziata senza previa pubblicazione del bando di gara ai sensi dell’articolo 122 comma 7 e dell’articolo 57 comma 6 del D.Lgs. n° 163 del 12.04.2006. Criterio di aggiudicazione dell’appalto: Del prezzo più basso, determinato mediante ribasso sull’importo dei lavori posto a base di gara, al netto del costo per il personale e degli oneri per l’attuazione dei piani della sicurezza entrambi non soggetti a ribasso d’asta, ai sensi dell’articolo 82 comma 2 lettera b), con esclusione automatica delle offerte anomale individuate ai sensi dell’articolo 86 comma 1 e dall’articolo 122 comma 9 entrambi del D.Lgs. -

Bando Legna Pantaleo

Graduatoria Legna da ardere Foresta Demaniale Pantaleo (Nuxis - Santadi) sorteggio del 12/07/2010 Nominativo Indirizzo 1 Caboni Giovanni Piazza Repubblica s.n. Santadi 2 Secci Pinuccio S.S. n°293 n°13 Villaperuccio 3 Nonnis Riccardo Via del Calabrese n°51 Narcao 4 Secci Anna Rita Via Crabi' n°4 Santadi 5 Mei Enrico Via Is Pireddas n°26 Villaperuccio 6 Cocco Iolanda Via Del Calabrese n°22/a Narcao 7 Piddiu Monica Via Campidano n°11 Nuxis 8 Floris Maria Via G. Ziranu n°9 Santadi 9 Pintus Alessio Via Mazzini n°4 Piscinas 10 Spada Francesca Via Dei Corbezzoli n°16 Teulada 11 Collu Luciano Via Santa Lucia n°2 Santadi 12 Porcu Lorenzo Via Sardegna n°4/a Villaperuccio 13 Atzeni Grazietta Via Risorgimento n°8 Santadi 14 Garia Claudio Via B. Argiolu n°13 Villaperuccio 15 Cogotti Genoveffa Via Fontane n°80 Santadi 16 De Marco Roberta Via Rio Mortu n°62 Monserrato 17 Mocci Massimo Vico Andrea Pinna 34/b Santadi 18 Cara Mauro Via Amsicora n°4 Villamassargia 19 Carvone Guido Via Camposanto n°10 Villaperuccio 20 Secci Basilio Via Fontane n°76 Santadi 21 Piras Tunny Via Terresoli n°75 Santadi 22 Sanna Katia Via Sardegna n°5 Nuxis 23 Melis Maria Teresa Via Macomer n°15 Santadi 24 Casti Sinzu Pietro Paolo Via Terresoli n°168 Santad i 25 Nocera Antioco Via Francesco Ciusa n°20 Sant'Antioc o 26 Trastus Alessandro Via Cagliari n°91 Santadi 27 Cani Bruna Via Cavour n°3 Santadi 28 Forresu Isabella Via Umberto I° n°26 Santadi 29 Aresu Gianni Via Is Cotzas n°2 Villaperuccio 30 Pintus Maria Giovanna Via Garibaldi n°6 Villaperucc io 31 Lobina Maria Vico II° Nazionale n°3 Villaperuccio 32 Pinna Elio Via Marche n°1 Santadi 33 Floris Angelo Roberto Via G. -

Elenco Corse

Centro Interuniversitario Regione Autonoma della Sardegna Provincia dell’Ogliastra Ricerche economiche e mobilità PROVINCIA DELL’OGLIASTRA ELENCO CORSE PROGETTO DEFINITIVO Centro Interuniversitario Regione Autonoma della Sardegna Provincia dell’Ogliastra Ricerche economiche e mobilità UNIVERSITÁ DEGLI STUDI DI CAGLIARI CIREM CENTRO INTERUNIVERSITARIO RICERCHE ECONOMICHE E MOBILITÁ Responsabile Scientifico Prof. Ing. Paolo Fadda Coordinatore Tecnico/Operativo Dott. Ing. Gianfranco Fancello Gruppo di lavoro Ing. Diego Corona Ing. Giovanni Durzu Ing. Paolo Zedda Centro Interuniversitario Regione Autonoma della Sardegna Provincia dell’Ogliastra Ricerche economiche e mobilità SCHEMA DEI CORRIDOI ORARIO CORSE CORSE ‐ OGLIASTRA ‐ ANDATA RITORNO CORRIDOIO "GENNA e CRESIA" CORRIDOIO "GENNA e CRESIA" Partenza Arrivo Nome Linee Nome Corsa Km Origine Destinazione Tipologia Veicolo Partenza Arrivo Nome Linee Nome Corsa Km Origine Destinazione Tipologia Veicolo 06:15 07:25 LINEA ROSSA 3630 C1 ‐ fer 40,151 JERZU ARBATAX BUS_15_POSTI A 17:40 18:50 LINEA ROSSA 3630 C1 ‐ fer 40,151 ARBATAX JERZU BUS_15_POSTI R 06:50 08:00 LINEA ROSSA 3630 C ‐ scol 43,012 OSINI NUOVO TORTOLI' STAZIONE FDS BUS_55_POSTI A 13:40 14:50 LINEA ROSSA 3630 C ‐ scol 43,012 TORTOLI' STAZIONE FDS OSINI NUOVO BUS_55_POSTI R 07:00 07:45 LINEA ROSSA 3511 C2 ‐ scol 28,062 LANUSEI PIAZZA V. EMANUELE1 JERZU BUS_55_POSTI A 13:42 14:27 LINEA ROSSA 3511 C2 ‐ scol 28,062 JERZU LANUSEI PIAZZA V. EMANUELE1 BUS_55_POSTI R 07:15 08:00 LINEA ROSSA 3511 C1 ‐ scol 28,062 JERZU LANUSEI PIAZZA V. EMANUELE1 BUS_55_POSTI A 13:42 14:27 LINEA ROSSA 3511 C1 ‐ scol 28,062 LANUSEI PIAZZA V. EMANUELE1 JERZU BUS_55_POSTI R 07:30 07:58 LINEA ROSSA 3 C ‐ scol 18,316 BARI SARDO LANUSEI PIAZZA V. -

Orari E Percorsi Della Linea Bus

Orari e mappe della linea bus 802 802 Cagliari Autostazione Arst Visualizza In Una Pagina Web La linea bus 802 (Cagliari Autostazione Arst) ha 6 percorsi. Durante la settimana è operativa: (1) Cagliari Autostazione Arst: 07:53 (2) Calasetta Porto: 03:23 - 21:10 (3) Carbonia Centro Intermodale: 07:05 (4) Carbonia Centro Intermodale: 04:20 - 22:15 (5) Siliqua Via Cixerri 27: 06:05 (6) Villamassargia Stazione FS: 05:33 Usa Moovit per trovare le fermate della linea bus 802 più vicine a te e scoprire quando passerà il prossimo mezzo della linea bus 802 Direzione: Cagliari Autostazione Arst Orari della linea bus 802 6 fermate Orari di partenza verso Cagliari Autostazione Arst: VISUALIZZA GLI ORARI DELLA LINEA lunedì 07:53 martedì 07:53 Siliqua Via Cixerri 27 mercoledì 07:53 Uta Stazione FS giovedì 07:53 Cagliari V.Le Sant'Avendrace 252 venerdì 07:53 242 Viale Sant'Avendrace, Cagliari sabato 07:53 Cagliari V.Le Trieste-Ee.Ll. 188 Viale Trieste, Cagliari domenica Non in servizio Cagliari Via Roma 86 86 Via Roma, Cagliari Cagliari Autostazione Arst Informazioni sulla linea bus 802 3 Via Molo Sant'agostino, Cagliari Direzione: Cagliari Autostazione Arst Fermate: 6 Durata del tragitto: 43 min La linea in sintesi: Siliqua Via Cixerri 27, Uta Stazione FS, Cagliari V.Le Sant'Avendrace 252, Cagliari V.Le Trieste-Ee.Ll., Cagliari Via Roma 86, Cagliari Autostazione Arst Direzione: Calasetta Porto Orari della linea bus 802 50 fermate Orari di partenza verso Calasetta Porto: VISUALIZZA GLI ORARI DELLA LINEA lunedì 03:23 - 21:10 martedì 03:23 - 21:10 Cagliari Autostazione Arst 3 Via Molo Sant'agostino, Cagliari mercoledì 03:23 - 21:10 Cagliari Viale Trieste-Ass.To Turismo giovedì 03:23 - 21:10 105 Viale Trieste, Cagliari venerdì 03:23 - 21:10 Cagliari V.Le Trieste-Ee.Ll. -

Proposal Bay of Naples

Independent 'Self Guided' walking tour Wild Sardinia Hiking along the spectacular east coast of Sardinia Wild nature, ancient cultures & stunning beaches TRIP NOTES 2021 © Genius Loci Travel. All rights reserved. [email protected] | www.genius-loci.it ***GENIUS LOCI TRAVEL - The Real Spirit Of Italy*** Independent 'Self Guided' walking tour INTRODUCTION The island of Sardinia has long been known for its dazzling sandy beaches and clear crystalline sea, and is immensely popular as a summer retreat not only for the happy few, but also the more ordinary tourist. Only recently its many unspoilt natural and cultural treasures have gotten the right attention from nature lovers. It is still possible to wander its many spectacular trails, enjoying the peace and quiet of a true hiker’s paradise. Your trip will take you to the heartland of the wild Supramonte region along Sardinia’s east coast, without doubt the island’s most spectacular area for trekking. Here sheer limestone cliffs coloured by wildflowers and the fruits of strawberry trees drop down vertically into the blue Mediterranean Sea, where little sandy beaches open up on vertiginous gorges. Small cultivated valleys carry the fruits of man’s labour: above all olive groves and vineyards yielding splendid local wines. Wild animals such as wild boar, Sardinian wild sheep or mouflons, and many species of birds of prey, including eagles, roam the barren karst plateaus of the mountain ranges occasionally descending into the verdant valleys where lucky encounters with hikers are not uncommon. During the first days of your trip you will explore the heartland of the Supramonte of Oliena. -

Official Journal C 3 of the European Union

Official Journal C 3 of the European Union Volume 62 English edition Information and Notices 7 January 2019 Contents IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2019/C 3/01 Euro exchange rates .............................................................................................................. 1 NOTICES FROM MEMBER STATES 2019/C 3/02 Notice inviting proposals for the transfer of an extraction area for hydrocarbon extraction ................ 2 2019/C 3/03 Communication from the Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Policy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands pursuant to Article 3(2) of Directive 94/22/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the conditions for granting and using authorisations for the prospection, exploration and production of hydrocarbons ................................................................................................... 4 V Announcements PROCEDURES RELATING TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF COMPETITION POLICY European Commission 2019/C 3/04 Prior notification of a concentration (Case M.9148 — Univar/Nexeo) — Candidate case for simplified procedure (1) ........................................................................................................................ 6 EN (1) Text with EEA relevance. OTHER ACTS European Commission 2019/C 3/05 Publication of the amended single document following the approval of a minor amendment pursuant to the second subparagraph of Article 53(2) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 ............................. -

Field T Rip Guide Book

Volume n° 5 - from P37 to P54 32nd INTERNATIONAL GEOLOGICAL CONGRESS HYDROGEOLOGY OF THE ISLAND OF SARDINIA (ITALY) Leader: G. Barrocu Field Trip Guide Book - P37 Field Trip Associate Leader: A. Vernier Florence - Italy August 20-28, 2004 Post-Congress P37 P37_copertina_R_OK C 26-05-2004, 11:03:05 The scientific content of this guide is under the total responsibility of the Authors Published by: APAT – Italian Agency for the Environmental Protection and Technical Services - Via Vitaliano Brancati, 48 - 00144 Roma - Italy Series Editors: Luca Guerrieri, Irene Rischia and Leonello Serva (APAT, Roma) English Desk-copy Editors: Paul Mazza (Università di Firenze), Jessica Ann Thonn (Università di Firenze), Nathalie Marléne Adams (Università di Firenze), Miriam Friedman (Università di Firenze), Kate Eadie (Freelance indipendent professional) Field Trip Committee: Leonello Serva (APAT, Roma), Alessandro Michetti (Università dell’Insubria, Como), Giulio Pavia (Università di Torino), Raffaele Pignone (Servizio Geologico Regione Emilia-Romagna, Bologna) and Riccardo Polino (CNR, Torino) Acknowledgments: The 32nd IGC Organizing Committee is grateful to Roberto Pompili and Elisa Brustia (APAT, Roma) for their collaboration in editing. Graphic project: Full snc - Firenze Layout and press: Lito Terrazzi srl - Firenze P37_copertina_R_OK D 26-05-2004, 11:02:12 Volume n° 5 - from P37 to P54 32nd INTERNATIONAL GEOLOGICAL CONGRESS HYDROGEOLOGY OF THE ISLAND OF SARDINIA (ITALY) AUTHORS: G. Barrocu, A. Vernier, F. Ardau (Editor), N. Salis, F. Sanna, M.G. Sciabica, S. Soddu (Università di Cagliari - Italy) Florence - Italy August 20-28, 2004 Post-Congress P37 P37_R_OK A 26-05-2004, 11:05:51 Front Cover: Su Gologone spring P37_R_OK B 26-05-2004, 11:05:53 HYDROGEOLOGY OF THE ISLAND OF SARDINIA (ITALY) P37 Leader: G.