Human Development Report 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF)

Public Disclosure Authorized PUNJAB MUNICIPAL SERVICES IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (PMSIP) Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework Draft April 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by: Punjab Municipal Infrastructure Development Company, Department of Local Government, Government of Punjab Public Disclosure Authorized i TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... VI CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 13 1.1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................ 13 1.2 PURPOSE OF THE ESMF .................................................................................................................................. 13 1.3 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................ 13 CHAPTER 2: PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................... 15 2.1 PROJECT COMPONENTS .................................................................................................................................... 15 2.2 PROJECT COMPONENTS AND IMPACTS................................................................................................................ -

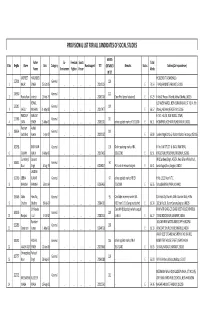

Provisional List for All Candidates of Social Studies

PROVISIONAL LIST FOR ALL CANDIDATES OF SOCIAL STUDIES MARKS Father Ex- Freedom Sports Total S No. RegNo Name Dob Category Handicapped TET OBTAINEDFile No. Remarks Status Address(Correspondence) Name Servicemen Fighter Person Marks IN TET JASPREET HARJINDER HOUSE NO. T/42 MOHALLA 217801 General 120 1 KAUR SINGH 25-Oct-85 ... ... ... ... 20013229 - E 70.54 TALAB,FARIDKOT,FARIDKOT,151203 230960 General 112 2 Punita Rani Inderjit 15-Feb-79 ... ... ... ... 20062706 Done Ph.d. (proof attached) E 67.29 H.No.82 Phase-6 Mohali,Mohali,Mohali,160055 KEWAL C/O VIVEK MANZIL. NEW SURAJ NAGARI, ST. NO. 4, 9th 220213 General 109 3 SHELLY KRISHAN 31-May-80 ... ... ... ... 20017477 - E 66.57 chowk,,ABOHAR,FEROZEPUR,152116 PARDEEP MALKIAT H .NO. : 613/B, NEW MODEL TOWN, 213383 General 101 4 SAINI SINGH 15-May-81 ... ... ... ... 20035201 online applied marks of 757/1000 E 66.11 HOSIARPUR,HOSHIARPUR,HOSIARPUR,146001 Poonam Ashok 198664 General 109 5 Sachdeva Kumar 1-Apr-87 ... ... ... ... 20022252 - E 65.89 Sunder Nagri St.No.6, Abohar,Abohar,Ferozepur,152116 103768 BHIM SAIN General 110 Online applying marks of BA H. No. B.M. 37/27, St. BAOLI RAM DYAL, 6 SUMAN MALIK 8-May-80 ... ... ... ... 20017453 1356/2200 E 65.51 FEROZEPUR,FEROZEPUR,FEROZEPUR,152002 Gurinderjit Jaswant W/O Sandeep Singh, 403/2A, Near Bihare Wala Khuh, 146851 General 94 7 Kaur Singh 6-Aug-79 ... ... ... ... 60040057 PG is not of relevant subject E 65.41 Janta Nagar,Dhuri,Sangrur,148024 JAGDISH 122780 LEENA KUMAR General 97 online applied marks of B.ED H.No. 1313, Near N.T.C. -

Notification Pgm-Cet-2014

No.DMER/PGM-CET 2014/Question Paper/Notification No.5/2-A, Date : 28/01/2014. NOTIFICATION PGM-CET-2014 The Common Entrance Test for Postgraduate Medical Courses, PGM-CET-2014 was conducted on Sunday, 5th January, 2014 by Competent Authority appointed by Government of Maharashtra. The provisional result of the same is being declared on 28th January 2014. The subject experts have opined that seven (07) questions in the question paper of the aforesaid examination are defective. The Competent Authority, on the basis of the opinion and advice of the respective subject expert has taken a decision to make these seven (07) questions "non-evaluative / invalid". These questions carried one mark each for a correct answer. Therefore instead of reducing the maximum number of marks from 300 to 293, The Competent Authority has decided to allot one mark each for these defective MCQ to all candidates who appeared in this examination, thus keeping maximum marks as 300; unchanged. The details of "Non-evaluative/ Invalid" MCQ are shown in the Table No. - 1 at respective Sr. No. in each version. Table No. – 1 – Version-wise Sr. No. of Non-evaluative/ Invalid Questions Sr. No. in Sr. No. in Sr. No. Sr. No. Sr. No. Version 11 Version 22 in Version 33 in Version 44 1 54 44 19 294 2 60 75 50 25 3 129 164 139 114 4 157 202 177 152 5 181 21 296 271 6 194 184 159 134 7 199 134 109 84 The subject expert also opined that there is change in Answer Key in Four (04) questions. -

Transfer Orders of Primary Cadre

O/o Director Public Instructions (EE), Punjab Order No: Dy SPD (PEDB)/2019/ 2019236032 Date:14-08-2019 Having considered your online application for transfer against available vacancy and in accordance with the Transfer Policy notified by the Department of School Education the following CHT/ HT/ ETT are hereby transferred with immediate effect: Sr. No. Staff ID Name Designation From School To School 1 118914870 PARMJEET SINGH CENTER HEAD TEACHER BATHINDA-GPS TALWANDI SABO BATHINDA-GPS SINGO 2 140189109 SOHAN SINGH CENTER HEAD TEACHER AMRITSAR -GPS KOTLA SULTAN SINGH AMRITSAR -GPS PANDORI WARAICH 3 205451820 PERMINDER SINGH CENTER HEAD TEACHER HOSHIARPUR-GPS DHUGGA KALAN HOSHIARPUR-GPS RUPOWAL 4 227250699 JAGSIR SINGH CENTER HEAD TEACHER BATHINDA-GPS PATTI KALA MEHRAJ BATHINDA-GPS AKLIA JALAL 5 252330218 IRVINDER KUMAR VERMA CENTER HEAD TEACHER PATIALA-GPS DAHRIAN PATIALA-GPS DAMANHERI 6 287358533 PRITPAL SINGH CENTER HEAD TEACHER FATEHGARH SAHIB-GPS RANWAN FATEHGARH SAHIB-GPS BADLA 7 311790889 Gurtej Singh CENTER HEAD TEACHER MOGA-GPS DALA B MOGA-GPS CHUGAWAN 8 390694710 Chhinderpal kaur CENTER HEAD TEACHER BATHINDA-GPS BALLUANA BATHINDA-GPS KILLI NIHAL SINGH WALA 9 436081158 Hardeep Singh CENTER HEAD TEACHER FEROZEPUR-GPS KARRI KALAN FEROZEPUR-GPS CANAL COLONY 10 494341234 CHIMAN LAL CENTER HEAD TEACHER AMRITSAR -GPS BHANGWAN AMRITSAR -GPS WADALA 11 623293667 Jangpal singh CENTER HEAD TEACHER LUDHIANA-GPS GAGRA LUDHIANA-GPS DADAHOOR 12 692130825 SURINDER SINGH CENTER HEAD TEACHER BATHINDA-GPS NATHANA Boys BATHINDA-GPS BAJJOANA 13 765024351 -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

Roll Number.Pdf

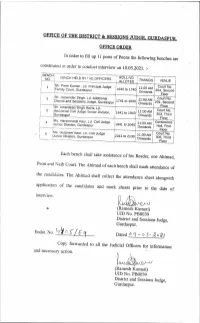

POST APPLIED FOR :- PEON Roll No. Application No. Name Father’s Name/ Husband’s Name Permanent Address 1 284 Aakash Subash Chander Hno 241/2 Mohalla Nangal Kotli Mandi Gurdaspur 2 792 Aakash Gill Tarsem lal Village Abulkhair Jail Road, Gurdaspur 3 1171 Aakash Masih Joginder Masih Village Chuggewal 4 1014 Aakashdeep Wazir Masih Village Tariza Nagar, PO Dhariwal, Gurdaspur 5 2703 Abhay Saini Parvesh Saini house no DF/350,4 Marla Quarter Ram Nagar Pathankot 6 1739 Abhi Bhavnesh Kumar Ward No. 3, Hno. 282, Kothe Bhim Sen, Dinanagar 7 1307 Abhi Nandan Niranjan Singh VPO Bhavnour, tehsil Mukerian , District Hoshiarpur 8 1722 Abhinandan Mahajan Bhavnesh Mahajan Ward No. 3, Hno. 282, Kothe Bhim Sen, Dinanagar 9 305 Abhishek Danial Hno 145, ward No. 12, Line No. 18A Mill QTR Dhariwal, District Gurdaspur 10 465 Abhishek Rakesh Kumar Hno 1479, Gali No 7, Jagdambe Colony, Majitha Road , Amritsar 11 1441 Abhishek Buta Masih Village Triza Nagar, PO Dhariwal, Gurdaspur 12 2195 Abhishek Vijay Kumar Village Meghian, PO Purana Shalla, Gurdaspur 13 2628 Abhishek Kuldeep Ram VPO Rurkee Tehsil Phillaur District Jalandhar 14 2756 Abhishek Shiv Kumar H.No.29B, Nehru Nagar, Dhaki road, Ward No.26 Pathankot-145001 15 1387 Abhishek Chand Ramesh Chand VPO Sarwali, Tehsil Batala, District Gurdaspur 16 983 Abhishek Dadwal Avresh Singh Village Manwal, PO Tehsil and District Pathankot Page 1 POST APPLIED FOR :- PEON Roll No. Application No. Name Father’s Name/ Husband’s Name Permanent Address 17 603 Abhishek Gautam Kewal Singh VPO Naurangpur, Tehsil Mukerian District Hoshiar pur 18 1805 Abhishek Kumar Ashwani Kumar VPO Kalichpur, Gurdaspur 19 2160 Abhishek Kumar Ravi Kumar VPO Bhatoya, Tehsil and District Gurdaspur 20 1363 Abhishek Rana Satpal Rana Village Kondi, Pauri Garhwal, Uttra Khand. -

Administrative Atlas , Punjab

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 PUNJAB ADMINISTRATIVE ATLAS f~.·~'\"'~ " ~ ..... ~ ~ - +, ~... 1/, 0\ \ ~ PE OPLE ORIENTED DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, PUNJAB , The maps included in this publication are based upon SUNey of India map with the permission of the SUNeyor General of India. The territorial waters of India extend into the sea to a distance of twelve nautical miles measured from the appropriate base line. The interstate boundaries between Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Meghalaya shown in this publication are as interpreted from the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971 but have yet to be verified. The state boundaries between Uttaranchal & Uttar Pradesh, Bihar & Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh & Madhya Pradesh have not been verified by government concerned. © Government of India, Copyright 2006. Data Product Number 03-010-2001 - Cen-Atlas (ii) FOREWORD "Few people realize, much less appreciate, that apart from Survey of India and Geological Survey, the Census of India has been perhaps the largest single producer of maps of the Indian sub-continent" - this is an observation made by Dr. Ashok Mitra, an illustrious Census Commissioner of India in 1961. The statement sums up the contribution of Census Organisation which has been working in the field of mapping in the country. The Census Commissionarate of India has been working in the field of cartography and mapping since 1872. A major shift was witnessed during Census 1961 when the office had got a permanent footing. For the first time, the census maps were published in the form of 'Census Atlases' in the decade 1961-71. Alongwith the national volume, atlases of states and union territories were also published. -

Growth of Urban Population in Malwa (Punjab)

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 8, Issue 7, July 2018 34 ISSN 2250-3153 Growth of Urban Population in Malwa (Punjab) Kamaljit Kaur DOI: 10.29322/IJSRP.8.7.2018.p7907 http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.8.7.2018.p7907 Abstract: This study deals with the spatial analysis of growth of urban population. Malwa region has been taken as a case study. During 1991-2001, the urban growth has been shown in Malwa region of Punjab. The large number of new towns has emerged in this region during 1991-2001 periods. Urban growth of Malwa region as well as distribution of urban centres is closely related to accessibility and modality factors. The large urban centres are located along major arteries. International border with an unfriendly neighbour hinders urban growth. It indicates that secondary activities have positive correlation with urban growth. More than 90% of urban population of Malwa region lives in large and medium towns of Punjab. More than 50% lives in large towns. Malwa region is agriculturally very prosperous area. So Mandi towns are well distributed throughout the region. Keywords: Growth, Urban, Population, Development. I. INTRODUCTION The distribution of urban population and its growth reflect the economic structure of population as well as economic growth of the region. The urban centers have different socio economic value systems, degree of socio-economic awakening than the rural areas. Although Urbanisation is an inescapable process and is related to the economic growth of the region but regional imbalances in urbanization creates problems for Planners so urban growth need to be channelized in planned manner and desired direction. -

Punjab: a Background

2. Punjab: A Background This chapter provides an account of Punjab’s Punjab witnessed important political changes over history. Important social and political changes are the last millennium. Its rulers from the 11th to the traced and the highs and lows of Punjab’s past 14th century were Turks. They were followed by are charted. To start with, the chapter surveys the Afghans in the 15th and 16th centuries, and by Punjab’s history up to the time India achieved the Mughals till the mid-18th century. The Sikhs Independence. Then there is a focus on the Green ruled over Punjab for over eighty years before the Revolution, which dramatically transformed advent of British rule in 1849. The policies of the Punjab’s economy, followed by a look at the Turko-Afghan, Mughal, Sikh and British rulers; and, tumultuous period of Naxalite-inspired militancy in the state. Subsequently, there is an account of the period of militancy in the state in the 1980s until its collapse in the early 1990s. These specific events and periods have been selected because they have left an indelible mark on the life of the people. Additionally, Punjab, like all other states of the country, is a land of three or four distinct regions. Often many of the state’s characteristics possess regional dimensions and many issues are strongly regional. Thus, the chapter ends with a comment on the regions of Punjab. History of Punjab The term ‘Punjab’ emerged during the Mughal period when the province of Lahore was enlarged to cover the whole of the Bist Jalandhar Doab and the upper portions of the remaining four doabs or interfluves. -

Role of Dalit Diaspora in the Mobility of the Disadvantaged in Doaba Region of Punjab

DOI: 10.15740/HAS/AJHS/14.2/425-428 esearch aper ISSN : 0973-4732 Visit us: www.researchjournal.co.in R P AsianAJHS Journal of Home Science Volume 14 | Issue 2 | December, 2019 | 425-428 Role of dalit diaspora in the mobility of the disadvantaged in Doaba region of Punjab Amanpreet Kaur Received: 23.09.2019; Revised: 07.11.2019; Accepted: 21.11.2019 ABSTRACT : In Sikh majority state Punjab most of the population live in rural areas. Scheduled caste population constitute 31.9 per cent of total population. Jat Sikhs and Dalits constitute a major part of the Punjab’s demography. From three regions of Punjab, Majha, Malwa and Doaba,the largest concentration is in the Doaba region. Proportion of SC population is over 40 per cent and in some villages it is as high as 65 per cent.Doaba is famous for two factors –NRI hub and Dalit predominance. Remittances from NRI, SCs contributed to a conspicuous change in the self-image and the aspirations of their families. So the present study is an attempt to assess the impact of Dalit diaspora on their families and dalit community. Study was conducted in Doaba region on 160 respondents. Emigrants and their families were interviewed to know about remittances and expenditure patterns. Information regarding philanthropy was collected from secondary sources. Emigration of Dalits in Doaba region of Punjab is playing an important role in the social mobility. They are in better socio-economic position and advocate the achieved status rather than ascribed. Majority of them are in Gulf countries and their remittances proved Authror for Correspondence: fruitful for their families. -

'Ambedkar's Constitution': a Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 2 No. 1 pp. 109–131 brandeis.edu/j-caste April 2021 ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v2i1.282 ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’: A Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste Discourse? Anurag Bhaskar1 Abstract During the last few decades, India has witnessed two interesting phenomena. First, the Indian Constitution has started to be known as ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’ in popular discourse. Second, the Dalits have been celebrating the Constitution. These two phenomena and the connection between them have been understudied in the anti-caste discourse. However, there are two generalised views on these aspects. One view is that Dalits practice a politics of restraint, and therefore show allegiance to the Constitution which was drafted by the Ambedkar-led Drafting Committee. The other view criticises the constitutional culture of Dalits and invokes Ambedkar’s rhetorical quote of burning the Constitution. This article critiques both these approaches and argues that none of these fully explores and reflects the phenomenon of constitutionalism by Dalits as an anti-caste social justice agenda. It studies the potential of the Indian Constitution and responds to the claim of Ambedkar burning the Constitution. I argue that Dalits showing ownership to the Constitution is directly linked to the anti-caste movement. I further argue that the popular appeal of the Constitution has been used by Dalits to revive Ambedkar’s legacy, reclaim their space and dignity in society, and mobilise radically against the backlash of the so-called upper castes. Keywords Ambedkar, Constitution, anti-caste movement, constitutionalism, Dalit Introduction Dr. -

Song and Memory: “Singing from the Heart”

SONG AND MEMORY: “SINGING FROM THE HEART” hir kIriq swDsMgiq hY isir krmn kY krmw ] khu nwnk iqsu BieE prwpiq ijsu purb ilKy kw lhnw ]8] har kīrat sādhasangat hai sir karaman kai karamā || kahu nānak tis bhaiou parāpat jis purab likhē kā lahanā ||8|| Singing the Kīrtan of the Lord’s Praises in the Sādh Sangat, the Company of the Holy, is the highest of all actions. Says Nānak, he alone obtains it, who is pre-destined to receive it. (Sōrath, Gurū Arjan, AG, p. 641) The performance of devotional music in India has been an active, sonic conduit where spiritual identities are shaped and forged, and both history and mythology lived out and remembered daily. For the followers of Sikhism, congregational hymn singing has been the vehicle through which melody, text and ritual act as repositories of memory, elevating memory to a place where historical and social events can be reenacted and memorialized on levels of spiritual significance. Hymn-singing services form the magnetic core of Sikh gatherings. As an intimate part of Sikh life from birth to death, Śabad kīrtan’s rich kaleidoscope of singing and performance styles act as a musical and cognitive archive bringing to mind a collective memory, uniting community to a common past. As a research scholar and practitioner of Gurmat Sangīt, I have observed how hymn singing plays such a significant role in understanding the collective, communal and egalitarian nature of Sikhism. The majority of events that I attended during my research in Punjab involved congregational singing: whether seated in the Gūrdwāra, or walking in a procession, the congregants were often actively engaged in singing.