Conserving Borderline Species Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Revised February 24, 2017 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. -

Surveys for Dun Skipper (Euphyes Vestris) in the Harrison Lake Area, British Columbia, July 2009

Surveys for Dun Skipper (Euphyes vestris) in the Harrison Lake Area, British Columbia, July 2009 Report Citation: Parkinson, L., S.A. Blanchette, J. Heron. 2009. Surveys for Dun Skipper (Euphyes vestris) in the Harrison Lake Area, British Columbia, July 2009. B.C. Ministry of Environment, Ecosystems Branch, Wildlife Science Section, Vancouver, B.C. 51 pp. Cover illustration: Euphyes vestris, taken 2007, lower Fraser Valley, photo by Denis Knopp. Photographs may be used without permission for non-monetary and educational purposes, with credit to this report and photographer as the source. The cover photograph is credited to Denis Knopp. Contact Information for report: Jennifer Heron, Invertebrate Specialist, B.C. Ministry of Environment, Ecosystems Branch, Wildlife Science Section, 316 – 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, B.C., Canada, V6T 1Z1. Phone: 604-222-6759. Email: [email protected] Acknowledgements Fieldwork was conducted by Laura Parkinson and Sophie-Anne Blanchette, B.C. Conservation Corps Invertebrate Species at Risk Crew. Jennifer Heron (B.C. Ministry of Environment) provided maps, planning and guidance for this project. The B.C. Invertebrate Species at Risk Inventory project was administered by the British Columbia Conservation Foundation (Joanne Neilson). Funding was provided by the B.C. Ministry of Environment through the B.C. Conservation Corp program (Ben Finkelstein, Manager and Bianka Sawicz, Program Coordinator), the B.C. Ministry of Environment Wildlife Science Section (Alec Dale, Manager) and Conservation Framework Funding (James Quayle, Manager). Joanne Neilson (B.C. Conservation Foundation) was a tremendous support to this project. This project links with concurrent invertebrate stewardship projects funded by the federal Habitat Stewardship Program for species at risk. -

November December 2010 Vol 67.3 Victoria Natural

NOVEMBER DECEMBER 2010 VOL 67.3 VICTORIA NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY The Victoria Naturalist Vol. 67.3 (2010) 1 Published six times a year by the SUBMISSIONS VICTORIA NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY, P.O. Box 5220, Station B, Victoria, BC V8R 6N4 Deadline for next issue: December 1, 2010 Contents © 2010 as credited. Send to: Claudia Copley ISSN 0049—612X Printed in Canada 657 Beaver Lake Road, Victoria BC V8Z 5N9 Editors: Claudia Copley, 250-479-6622, Penelope Edwards Phone: 250-479-6622 Desktop Publishing: Frances Hunter, 250-479-1956 e-mail: [email protected] Distribution: Tom Gillespie, Phyllis Henderson, Morwyn Marshall Printing: Fotoprint, 250-382-8218 Guidelines for Submissions Opinions expressed by contributors to The Victoria Naturalist Members are encouraged to submit articles, field trip reports, natural are not necessarily those of the Society. history notes, and book reviews with photographs or illustrations if possible. Photographs of natural history are appreciated along with VICTORIA NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY documentation of location, species names and a date. Please label your Honorary Life Members Dr. Bill Austin, Mrs. Lyndis Davis, submission with your name, address, and phone number and provide a Mr. Tony Embleton, Mr. Tom Gillespie, Mrs. Peggy Goodwill, title. We request submission of typed, double-spaced copy in an IBM compatible word processing file on diskette, or by e-mail. Photos and Mr. David Stirling, Mr. Bruce Whittington slides, and diskettes submitted will be returned if a stamped, self- Officers: 2009-2010 addressed envelope is included with the material. Digital images are PRESIDENT: Darren Copley, 250-479-6622, [email protected] welcome, but they need to be high resolution: a minimum of 1200 x VICE-PRESIDENT: James Miskelly, 250-477-0490, [email protected] 1550 pixels, or 300 dpi at the size of photos in the magazine. -

Willi Orchids

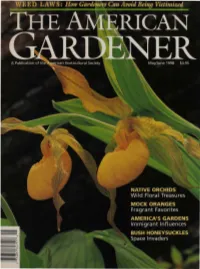

growers of distinctively better plants. Nunured and cared for by hand, each plant is well bred and well fed in our nutrient rich soil- a special blend that makes your garden a healthier, happier, more beautiful place. Look for the Monrovia label at your favorite garden center. For the location nearest you, call toll free l-888-Plant It! From our growing fields to your garden, We care for your plants. ~ MONROVIA~ HORTICULTURAL CRAFTSMEN SINCE 1926 Look for the Monrovia label, call toll free 1-888-Plant It! co n t e n t s Volume 77, Number 3 May/June 1998 DEPARTMENTS Commentary 4 Wild Orchids 28 by Paul Martin Brown Members' Forum 5 A penonal tour ofplaces in N01,th America where Gaura lindheimeri, Victorian illustrators. these native beauties can be seen in the wild. News from AHS 7 Washington, D . C. flower show, book awards. From Boon to Bane 37 by Charles E. Williams Focus 10 Brought over f01' their beautiful flowers and colorful America)s roadside plantings. berries, Eurasian bush honeysuckles have adapted all Offshoots 16 too well to their adopted American homeland. Memories ofgardens past. Mock Oranges 41 Gardeners Information Service 17 by Terry Schwartz Magnolias from seeds, woodies that like wet feet. Classic fragrance and the ongoing development of nell? Mail-Order Explorer 18 cultivars make these old favorites worthy of considera Roslyn)s rhodies and more. tion in today)s gardens. Urban Gardener 20 The Melting Plot: Part II 44 Trial and error in that Toddlin) Town. by Susan Davis Price The influences of African, Asian, and Italian immi Plants and Your Health 24 grants a1'e reflected in the plants and designs found in H eading off headaches with herbs. -

Atlantic Agriculture

FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS OF DALHOUSIE’S FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE SPRING 2021 Atlantic agriculture In memory Passing of Jim Goit In June 2020, campus was saddened with the sudden passing The Agricultural Campus and the Alumni Association of Jim Goit, former executive director, Development & External acknowledge the passing of the following alumni. We extend Relations. Jim had a long and lustrous 35-year career with the our deepest sympathy to family, friends and classmates. Province of NS, 11 of which were spent at NSAC (and the Leonard D’Eon 1940 Faculty of Agriculture). Jim’s impact on campus was Arnold Blenkhorn 1941 monumental – he developed NSAC’s first website, created Clara Galway 1944 an alumni and fundraising program and built and maintained Thomas MacNaughton 1946 many critical relationships. For his significant contributions, George Leonard 1947 Jim was awarded an honourary Barley Ring in 2012. Gerald Friars 1948 James Borden 1950 Jim retired in February 2012 and was truly living his best life. Harry Stewart 1951 On top of enjoying the extra time with his wife, Barb, their sons Stephen Cook 1954 and four grandchildren, he became highly involved in the Truro Gerald Foote 1956 Rotary Club and taught ski lessons in the winter. In retirement, Albert Smith 1957 Jim also enjoyed cooking, travelling, yard work and cycling. George Mauger 1960 Phillip Harrison 1960 In honour of Jim’s contributions to campus and the Alumni Barbara Martin 1962 Association, a bench was installed in front of Cumming Peter Dekker 1964 Hall in late November. Wayne Bhola Neil Murphy 1964 (Class of ’74) kindly constructed the Weldon Smith 1973 beautiful bench in Jim’s memory. -

Atlantic Canada Guidelines for Drinking Water Supply Systems

Water SupplySystems Storage, Distribution Atlant i c Canada Guidelines , andOperationof Atlantic Canada Guidelines for the Supply, for Treatment, Storage, t h Distribution, and e Supply, Operation of Drinking Water Supply Systems Dr i Treatment, n king September 2004 Prepared by: Coordinated by the Atlantic Canada Water Works Association (ACWWA) in association with the four Atlantic Canada Provinces WATER SYSTEM DESIGN GUIDELINE MANUAL PURPOSE AND USE OF MANUAL Page 1 PURPOSE AND USE OF MANUAL Purpose The purpose of the Atlantic Canada Guidelines for the Supply, Treatment, Storage, Distribution and Operation of Drinking Water Supply Systems is to provide a guide for the development of water supply projects in Atlantic Canada. The document is intended to serve as a guide in the evaluation of water supplies, and for the design and preparation of plans and specifications for projects. The document will suggest limiting values for items upon which an evaluation of such plans and specifications may be made by the regulator, and will establish, as far is practical, uniformity of practice. The document should be considered to be a companion to the Atlantic Canada Standards and Guidelines Manual for the Collection, Treatment and Disposal of Sanitary Sewage. Limitations Users of the Manual are advised that requirements for specific issues such as filtration, equipment redundancy, and disinfection are not uniform among the Atlantic Canada provinces, and that the appropriate regulator should be contacted prior to, or during, an investigation to discuss specific key requirements. Approval Process Chapter 1 of the Manual provides an overview of the approval process generally used by the regulators. -

Carolinian Zone Plant Guide

Carolinian Zone Plant Guide 1) Flowering Plants 2) Shrubs 3) Trees 4) Ferns 5) Grass 6) Vines 7) Water Plants Gardening Team UUHamilton 1 - Flowering Plants Common Blue Violet Gardening Team UUHamilton 1 - Carolinian Flowering Plants Carolinian moisture loving plants Cardinal flower Lobelia cardinalis Jewelweed Impatiens Swamp Milkweed Asclepias incarnata Joe Pyeweed Eupatorium fistulosum Boneset Eupatorium perfoliatum Bottle Gentian Gentiana andrewsii Turtlehead Chelone glabra Skunk cabbage Sympolcarpus Swamp aster Aster Canada lily Lilium canadense Ironweed Vernonia gigantea Bee balm Monarda fistulosa Jack in the pulpit Arisaema Carolinian Flowering Plants A & B Dense blazing star Liatris spicata Boneset Eupatorium perfolatum Canada Anemone Anemone canadensis Aster New England Symphyotrichum Aster novae-angliae White narrow leafed Heart leafed big leafed Sky blue flat top Daisy fleabane Calico swamp Butterfly weed Asciepios tuberose Bloodroot Sanguinara Canadensis Beebalm Monardo didyma Bergamot Monarda fistulosa Boneset Eupatorium perfoliatum Virginia Bluebell Uvalaria grandiflora Blazing star Liatris coreopsis Bugbane Virginia Bluebell Blanket flower Gaillardia Red Banebery Actaea ruba Perfoliate bellwort Golden Alexandrer's Zizia aurea Hairy Beardtongue Penstimon hirsutus C & D Coneflower purple Echinacea purpurea Coneflower grey headed Ratibida pinnata Compass Plant Silphium lociniaturm Lance - leafed coreopsis Coreopsis lanceolata Cardinal flower Lobelia cardinalis Culver's Root Veranicastrum Virginicum Cup Plant Silphium perfoliatum -

American Eel Anguilla Rostrata

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the American Eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 71 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge V. Tremblay, D.K. Cairns, F. Caron, J.M. Casselman, and N.E. Mandrak for writing the status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada, overseen and edited by Robert Campbell, Co-chair (Freshwater Fishes) COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Species Specialist Subcommittee. Funding for this report was provided by Environment Canada. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’anguille d'Amérique (Anguilla rostrata) au Canada. Cover illustration: American eel — (Lesueur 1817). From Scott and Crossman (1973) by permission. ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2004 Catalogue No. CW69-14/458-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43225-8 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name American eel Scientific name Anguilla rostrata Status Special Concern Reason for designation Indicators of the status of the total Canadian component of this species are not available. -

These De Doctorat De L'universite Paris-Saclay

NNT : 2016SACLS250 THESE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE PARIS-SACLAY, préparée à l’Université Paris-Sud ÉCOLE DOCTORALE N° 567 Sciences du Végétal : du Gène à l’Ecosystème Spécialité de doctorat (Biologie) Par Mlle Nour Abdel Samad Titre de la thèse (CARACTERISATION GENETIQUE DU GENRE IRIS EVOLUANT DANS LA MEDITERRANEE ORIENTALE) Thèse présentée et soutenue à « Beyrouth », le « 21/09/2016 » : Composition du Jury : M., Tohmé, Georges CNRS (Liban) Président Mme, Garnatje, Teresa Institut Botànic de Barcelona (Espagne) Rapporteur M., Bacchetta, Gianluigi Università degli Studi di Cagliari (Italie) Rapporteur Mme, Nadot, Sophie Université Paris-Sud (France) Examinateur Mlle, El Chamy, Laure Université Saint-Joseph (Liban) Examinateur Mme, Siljak-Yakovlev, Sonja Université Paris-Sud (France) Directeur de thèse Mme, Bou Dagher-Kharrat, Magda Université Saint-Joseph (Liban) Co-directeur de thèse UNIVERSITE SAINT-JOSEPH FACULTE DES SCIENCES THESE DE DOCTORAT DISCIPLINE : Sciences de la vie SPÉCIALITÉ : Biologie de la conservation Sujet de la thèse : Caractérisation génétique du genre Iris évoluant dans la Méditerranée Orientale. Présentée par : Nour ABDEL SAMAD Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR ÈS SCIENCES Soutenue le 21/09/2016 Devant le jury composé de : Dr. Georges TOHME Président Dr. Teresa GARNATJE Rapporteur Dr. Gianluigi BACCHETTA Rapporteur Dr. Sophie NADOT Examinateur Dr. Laure EL CHAMY Examinateur Dr. Sonja SILJAK-YAKOVLEV Directeur de thèse Dr. Magda BOU DAGHER KHARRAT Directeur de thèse Titre : Caractérisation Génétique du Genre Iris évoluant dans la Méditerranée Orientale. Mots clés : Iris, Oncocyclus, région Est-Méditerranéenne, relations phylogénétiques, status taxonomique. Résumé : Le genre Iris appartient à la famille des L’approche scientifique est basée sur de nombreux Iridacées, il comprend plus de 280 espèces distribuées outils moléculaires et génétiques tels que : l’analyse de à travers l’hémisphère Nord. -

Section 5 References

Section 5 References 5.0 REFERENCES Akçakaya, H. R. and J. L. Atwood. 1997. A habitat-based metapopulation model of the California Gnatcatcher. Conservation Biology 11:422-434. Akçakaya, H.R. 1998. RAMAS GIS: Linking landscape data with population viability analysis (version 3.0). Applied Biomathematics, Setaauket, New York. Anderson, D.W. and J.W. Hickey. 1970. Eggshell changes in certain North American birds. Ed. K. H. Voous. Proc. (XVth) Inter. Ornith. Congress, pp 514-540. E.J. Brill, Leiden, Netherlands. Anderson, D.W., J.R. Jehl, Jr., R.W. Risebrough, L.A. Woods, Jr., L.R. Deweese, and W.G. Edgecomb. 1975. Brown pelicans: improved reproduction of the southern California coast. Science 190:806-808. Atwood, J.L. 1980. The United States distribution of the California black-tailed gnatcatcher. Western Birds 11: 65-78. Atwood, J.L. 1990. Status review of the California gnatcatcher (Polioptila californica). Unpublished Technical Report, Manomet Bird Observatory, Manomet, Massachusetts. Atwood, J.L. 1992. A maximum estimate of the California gnatcatcher’s population size in the United States. Western Birds. 23:1-9. Atwood, J.L. and J.S. Bolsinger. 1992. Elevational distribution of California gnatcatchers in the United States. Journal of Field Ornithology 63:159-168. Atwood, J.L., S.H. Tsai, C.H. Reynolds, M.R. Fugagli. 1998. Factors affecting estimates of California gnatcatcher territory size. Western Birds 29: 269-279. Baharav, D. 1975. Movement of the horned lizard Phrynosoma solare. Copeia 1975: 649-657. Barry, W.J. 1988. Management of sensitive plants in California state parks. Fremontia 16(2):16-20. Beauchamp, R.M. -

Maine's Endangered and Threatened Plants

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Maine Collection 1990 Maine's Endangered and Threatened Plants Maine State Planning Office Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Forest Biology Commons, Forest Management Commons, Other Forestry and Forest Sciences Commons, Plant Biology Commons, and the Weed Science Commons Recommended Citation Maine State Planning Office, "Maine's Endangered and Threatened Plants" (1990). Maine Collection. 49. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection/49 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Collection by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BACKGROUND and PURPOSE In an effort to encourage the protection of native Maine plants that are naturally reduced or low in number, the State Planning Office has compiled a list of endangered and threatened plants. Of Maine's approximately 1500 native vascular plant species, 155, or about 10%, are included on the Official List of Maine's Plants that are Endangered or Threatened. Of the species on the list, three are also listed at the federal level. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. has des·ignated the Furbish's Lousewort (Pedicularis furbishiae) and Small Whorled Pogonia (lsotria medeoloides) as Endangered species and the Prairie White-fringed Orchid (Platanthera leucophaea) as Threatened. Listing rare plants of a particular state or region is a process rather than an isolated and finite event. -

National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands 1996

National List of Vascular Plant Species that Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary Indicator by Region and Subregion Scientific Name/ North North Central South Inter- National Subregion Northeast Southeast Central Plains Plains Plains Southwest mountain Northwest California Alaska Caribbean Hawaii Indicator Range Abies amabilis (Dougl. ex Loud.) Dougl. ex Forbes FACU FACU UPL UPL,FACU Abies balsamea (L.) P. Mill. FAC FACW FAC,FACW Abies concolor (Gord. & Glend.) Lindl. ex Hildebr. NI NI NI NI NI UPL UPL Abies fraseri (Pursh) Poir. FACU FACU FACU Abies grandis (Dougl. ex D. Don) Lindl. FACU-* NI FACU-* Abies lasiocarpa (Hook.) Nutt. NI NI FACU+ FACU- FACU FAC UPL UPL,FAC Abies magnifica A. Murr. NI UPL NI FACU UPL,FACU Abildgaardia ovata (Burm. f.) Kral FACW+ FAC+ FAC+,FACW+ Abutilon theophrasti Medik. UPL FACU- FACU- UPL UPL UPL UPL UPL NI NI UPL,FACU- Acacia choriophylla Benth. FAC* FAC* Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd. FACU NI NI* NI NI FACU Acacia greggii Gray UPL UPL FACU FACU UPL,FACU Acacia macracantha Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd. NI FAC FAC Acacia minuta ssp. minuta (M.E. Jones) Beauchamp FACU FACU Acaena exigua Gray OBL OBL Acalypha bisetosa Bertol. ex Spreng. FACW FACW Acalypha virginica L. FACU- FACU- FAC- FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acalypha virginica var. rhomboidea (Raf.) Cooperrider FACU- FAC- FACU FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acanthocereus tetragonus (L.) Humm. FAC* NI NI FAC* Acanthomintha ilicifolia (Gray) Gray FAC* FAC* Acanthus ebracteatus Vahl OBL OBL Acer circinatum Pursh FAC- FAC NI FAC-,FAC Acer glabrum Torr. FAC FAC FAC FACU FACU* FAC FACU FACU*,FAC Acer grandidentatum Nutt.