Courage to Dissent Oxford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Guide to the educational resources available on the GHS website Theme driven guide to: Online exhibits Biographical Materials Primary sources Classroom activities Today in Georgia History Episodes New Georgia Encyclopedia Articles Archival Collections Historical Markers Updated: July 2014 Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Table of Contents Pre-Colonial Native American Cultures 1 Early European Exploration 2-3 Colonial Establishing the Colony 3-4 Trustee Georgia 5-6 Royal Georgia 7-8 Revolutionary Georgia and the American Revolution 8-10 Early Republic 10-12 Expansion and Conflict in Georgia Creek and Cherokee Removal 12-13 Technology, Agriculture, & Expansion of Slavery 14-15 Civil War, Reconstruction, and the New South Secession 15-16 Civil War 17-19 Reconstruction 19-21 New South 21-23 Rise of Modern Georgia Great Depression and the New Deal 23-24 Culture, Society, and Politics 25-26 Global Conflict World War One 26-27 World War Two 27-28 Modern Georgia Modern Civil Rights Movement 28-30 Post-World War Two Georgia 31-32 Georgia Since 1970 33-34 Pre-Colonial Chapter by Chapter Primary Sources Chapter 2 The First Peoples of Georgia Pages from the rare book Etowah Papers: Exploration of the Etowah site in Georgia. Includes images of the site and artifacts found at the site. Native American Cultures Opening America’s Archives Primary Sources Set 1 (Early Georgia) SS8H1— The development of Native American cultures and the impact of European exploration and settlement on the Native American cultures in Georgia. Illustration based on French descriptions of Florida Na- tive Americans. -

Female Historical Figures and Historical Topics

Female Historical Figures and Historical Topics The Georgia Historical Society offers educational materials for teachers to use as resources in the classroom. Explore this document to find highlighted materials related to Georgia and women’s history on the GHS website. In this document, explore the Georgia Historical Society’s educational materials in two sections: Female Historical Figures and Historical Topics. Both sections highlight some of the same materials that can be used for more than one classroom standard or topic. Female Historical Figures There are many women in Georgia history that the Georgia Historical Society features that can be incorporated in the classroom. Explore the readily-available resources below about female figures in Georgia history and discover how to incorporate them into lessons through the standards. Abigail Minis SS8H2 Analyze the colonial period of Georgia’s history. a. Explain the importance of the Charter of 1732, including the reasons for settlement (philanthropy, economics, and defense). c. Evaluate the role of diverse groups (Jews, Salzburgers, Highland Scots, and Malcontents) in settling Georgia during the Trustee Period. e. Give examples of the kinds of goods and services produced and traded in colonial Georgia. • What group of settlers did the Minis family belong to, and how did this contribute to the settling of Georgia in the Trustee Period? • How did Abigail Minis and her family contribute to the colony of Georgia economically? What services and goods did they supply to the market? SS8H3 Analyze the role of Georgia in the American Revolutionary Era. c. Analyze the significance of the Loyalists and Patriots as a part of Georgia’s role in the Revolutionary War; include the Battle of Kettle Creek and Siege of Savannah. -

September, 2009

NOVEMBER, 2014 CURRICULUM VITAE DELORES P. ALDRIDGE, PH.D. GRACE TOWNS HAMILTON PROFESSOR OF SOCIOLOGY AND AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES EMORY UNIVERSITY ADDRESSES: Home: 2931 Yucca Drive Decatur, Georgia 30032 Area Code (404) 289-0272 Office: 228 Tarbutton Hall 1555 Dickey Drive Emory University Atlanta, Georgia, 30322 Email: [email protected] Phone: (404) 727-0534 EDUCATION: 1971 Ph.D. Purdue University (Sociology) 1967 Certificate, University of Ireland-Dublin (Child Psychology) 1966 M.S.W., Atlanta University (Social Casework and Community Organization) 1963 B.A., Clark College (Sociology/Psychology-Valedictorian) 1959 Middleton High School (College Preparatory-Valedictorian) Additional Educational Experiences 1980 Women in Higher Education Management Institute sponsored by Bryn Mawr College and Higher Education Resource Services Mid-Atlantic 2 1979 Postdoctoral Summer Educational Research Management Workshop sponsored by the National Academy of Education with a grant from the National Institute of Education, Georgetown University 1972 University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana - Summer Session courses in African History, art, and politics 1968 University of Montreal, Canada in collaboration with General Hospital -- Participated in six week training institute on family treatment techniques. The institute had twenty participants from both the USA and other countries. MAJOR WORK EXPERIENCES: Administrative Positions in Higher Education 1997 - Project Director, Project on Social and Economic Contributions of Women of Georgia, State of Georgia 1994 -

Atlanta University Bulletin Published Quarterly by Atlanta University ATLANTA, GEORGIA

The Atlanta University Bulletin Published Quarterly by Atlanta University ATLANTA, GEORGIA Entered as second-class matter February 28, 1935, at the Post Office at Atlanta, Georgia, under the Act of August 24, 1912. Acceptance for mailing at special rate of postage provided for in the Act of February 28, 1925, 538, P. L. & R. Series 111 JULY, 1943 No. 43 C^om m en com en t-1943 Out-of-doors for the first time in thirteen years Page 2 THE ATLANTA UNIVERSITY BULLETIN July, 1943 Bean page’s Beat!) M #reat HLo$$ to Atlanta fHntoersittp The death on July 1 of Mr. Dean Sage, lawyer and Mr. Sage was elected president of the Presbyterian philanthropist, and for the last fourteen years chairman Hospital, at Seventieth Street and Park Avenue, New of the board of trustees of Atlanta University, is a great York City, in November, 1922. On October 4, 1924, loss to the University and the affiliated institutions. he announced the plans for the construction of “the Mr. Sage died while on a fishing outing at Camp Har¬ greatest medical center in the world,” which was to cost mony, New Brunswick, Canada. He was in his sixty- more than $20,000,000 and to embody the latest de¬ eighth year. velopments in medical science, combining hospital, med¬ Since 1911, Mr. Sage had been a member of the board ical college and research work. and for a number of years he served as chairman of the The work in which he had played so prominent a finance committee. From the time of the affiliation of part was finished in 1928, on a twenty-acre site at Broad¬ Spelman College, Morehouse College and Atlanta Uni¬ way and 168th Street. -

Wilkins, Josephine Mathewson, 1893-1977

WILKINS, JOSEPHINE MATHEWSON, 1893-1977. Josephine Mathewson Wilkins papers,1920-1977 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Wilkins, Josephine Mathewson, 1893-1977. Title: Josephine Mathewson Wilkins papers,1920-1977 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 580 Extent: 48.25 linear feet (66 boxes), 3 oversized bound volumes (OBV), and 2 oversized papers boxes and 1 oversized papers folder (OP) Abstract: Papers of Georgia civil and social reform worker and philanthropist Josephine Mathewson Wilkins including correspondence, subject files, minutes, reports, financial records, press releases, clippings, and photographs. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Source Gift of Thomas H. Wilkins, 1978. Thomas H. Wilkins also donated an addition to the collection in 1986. In 2000, the Estate of Josephine Wilkins, represented by John J. Wilkins, III, donated an addition to the collection. Custodial History Thomas H. Wilkins and John J. Wilkins, III, are nephews of Josephine Mathewson Wilkins. Appraisal Note Acquired as part of the Rose Library's holdings in Georgia history. Processing Processed through a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, 1982 Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Josephine Mathewson Wilkins papers, 1920-1977 Manuscript Collection No. 580 This finding aid may include language that is offensive or harmful. -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

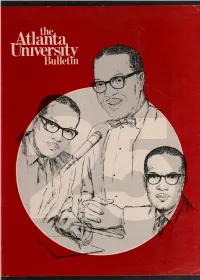

MARCH, 1973 Charter Day A POW Comes Home Dr. Smythe’s Address 6 Summer Commencement 10 Campus Briefs 16 Atlanta University Honors Dr. Jarrett for 25 years of service 24 Spotlight: Negro Collection of Art and Sculpture Reopened 26 Faculty Items 28 Alumni News 32 In Memoriam Cover: Atlanta University honors Dr. Jarrett for his 25 years of service. See page 24. SECOND CLASS POSTAGE PAID AT ATLANTA, GEORGIA Two distinguished graduates of At¬ lanta University came home for Charter Day—one of them a former ambassador to Syria and Malta, and Charter the other a recently released prisoner Day of war. Dr. Hugh H. Smythe, now professor An AmbassadorAnd A POW of Sociology at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York, and Come Home To Atlanta University Navy Lieutenant Norris Charles, a graduate of the School of Business Administration who was a POW of the North Vietnamese for nine months, joined trustees, faculty, staff and stu¬ dents in celebrating the granting of the university’s charter. Charter Day was held Monday, October 16. Dr. Smythe delivered the main ad¬ dress in Sisters Chapel. A graduate who earned a Master of Arts degree in Sociology in 1937, he served as U. S. Ambassador to Syria from 1965 to 1967, and as Ambassador to Malta from 1967 to 1969. Lt. Charles, who received the Master of Business Administration degree in 1968, was captured in De¬ cember, 1971, and was one of three prisoners released in September. He and his wife, Olga, a Spelman College Lt. Norris Charles and wife alumna, were Atlanta University's Olga. -

REQUEST for PROPOSALS for the REDEVELOPMENT of 594 University Place NW LOCATED in the VINE CITY NEIGHBORHOOD of ATLANTA

REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS FOR THE REDEVELOPMENT OF 594 University Place NW LOCATED IN THE VINE CITY NEIGHBORHOOD OF ATLANTA PREPARED BY: THE ATLANTA DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY D/B/A INVEST ATLANTA MARCH 30, 2020 RESPONSES DUE: MAY 11, 2020 Invest Atlanta 2 Request for Proposals 594 University Place NW Redevelopment REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS (“RFP”) Redevelopment of 594 University Place NW Atlanta, GA located in the Vine City neighborhood INTRODUCTION The Atlanta Development Authority d/b/a Invest Atlanta (“Invest Atlanta”) is soliciting responses to this Request for Proposals (“RFP”) from qualified developers and local non-profits (each, a “Respondent”) for a ground lease to redevelop and preserve the historic structure of 594 University Place NW Atlanta, GA formally the home of Grace Towns Hamilton to provide an educational, community asset for Vine City and overall Westside Neighborhoods. Invest Atlanta has been created and is existing under and by virtue of the Development Authorities Law, activated by a resolution of the City Council of the City of Atlanta, Georgia (the "City") and currently operates as a public body corporate and politic of the State of Georgia. Invest Atlanta was created to promote the revitalization and growth of the City and serves as the City’s Economic Development Agency. Invest Atlanta represents a consolidation of the City’s economic and community development efforts in real estate, finance, marketing and employment, for the purpose of providing a focal point for improving the City's neighborhoods and the quality of life for all of its citizens. BACKGROUND The property is currently owned by Invest Atlanta. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE February 29, 2000 Student Can Look up To

1760 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE February 29, 2000 student can look up to. Aleisha Cramer than its parent organization at the an advanced education degree, and had has proved what hard work as a stu- time. It was interracial far before the worked steadily at professional jobs for dent, athlete and community member first ‘‘Negro’’ was appointed to the more than a decade. She knew the can accomplish. board. After she graduated, the Na- value of community activism and edu- Again, I would like to congratulate tional YWCA offered her a secretarial cation and set out to take part in the Aleisha Cramer, the 1999–2000 Gatorade job in one of its Negro branches. A fa- fight. This led her to the Atlanta National High School Girls Soccer vorite psychology professor at AU had Urban League. Player of the Year, for her accomplish- a high regard for the psychology de- From 1943 until 1960, Grace Hamilton ments. She has made the State of Colo- partment at Ohio State and seeing as served as the Executive Director of the rado and this nation proud.∑ how the YWCA job would make it pos- Atlanta Urban League. During her ten- f sible to finance her post-graduate edu- ure, she shaped the path of the League cation at the same time, Grace decided to better serve Atlanta, which was in- GRACE TOWNS HAMILTON (1907– to go. creasingly being seen as the South’s 1992) Grace Towns later admitted that ‘‘hub city.’’ She moved the focus away ∑ Mr. CLELAND. Mr. President, ‘‘A po- there was no way she could have been from the national organization’s em- litical leader who changes his stances prepared for what she faced in Ohio. -

Hamilton, Grace Towns Interview Date: 1985-08-19 Transcription Date: 2014 Georgia Institute of Technology Archives, Ron Bayor Papers (MS450)

MS450_014 Interviewer: Bayor, Ronald H. Interviewee: Hamilton, Grace Towns Interview date: 1985-08-19 Transcription date: 2014 Georgia Institute of Technology Archives, Ron Bayor Papers (MS450) RONALD BAYOR: One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten. I wanted to ask you a few questions. First off things about politics, if that’s all right. GRACE TOWNS HAMILTON: Don’t take it as gospel. BAYOR: I was reading Harold Martin’s book on Hartsfield. He said that in 1953 Helen [Bullock?] spoke to you about what the mayor could do to retain black political support. Apparently John Wesley Dobbs had threatened to take his forces out of the Atlanta Negro Voters League because of Hartsfield unwillingness to hire black policemen -- black firemen. Apparently, according to his book, he -- (break in audio) HAMILTON: I remember that Mr. Walden, who was another very important figure in the development of Georgia political participation by Negroes had -- was the [01:00] chairman of -- and was a person whom I’d known all my life. He was an early [Atlanta?] -- the first to graduate -- was the first lawyer to practice in the courts of Georgia after he came back from Michigan. 1 BAYOR: A. T. Walden. HAMILTON: Right. And he was the chairman of the league board. I came to work with the league in 1943, and in 1946 the league -- not directly but served as a secretary for this - - for what came to be known as the All-Citizens Registration Committee. And we did this massive registration drive which in those days -- we were faced with the poll tax, with the white primary that -- all the difficulties. -

“Meeting the Needs of Today's Girl”: Youth Organizations and The

“Meeting the Needs of Today’s Girl”: Youth Organizations and the Making of a Modern Girlhood, 1945-1980 By Jessica L. Foley B.B.A., College of William and Mary, 2001 A.M., Brown University, 2005 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Jessica L. Foley This dissertation of Jessica L. Foley is accepted in its present form by the Department of History as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Mari Jo Buhle, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date Robert O. Self, Reader Date Richard A. Meckel, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iii VITA Jessica L. Foley was born in Virginia Beach, Virginia, on October 31, 1979. She attended the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, where she earned a B.B.A. in Finance with a double concentration in History in 2001. In 2005, she received an A.M. in History from Brown University, where she specialized in women’s history and the social and cultural history of twentieth-century America. Her dissertation research was primarily funded by Brown University and by the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women. She has taught at Brown University and Bristol Community College, and has served as a teaching assistant in courses on the history of the United States at Brown. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My deepest gratitude goes to everyone who has helped to make this project a reality. -

Atlanta University Bulletin Published, Quarterly by Atlanta University ATLANTA, GEORGIA

The Atlanta University Bulletin Published, Quarterly by Atlanta University ATLANTA, GEORGIA Entered as second-class matter February 28, 1935, at the Post Office at Atlanta, Georgia, under the Act of August 24, 1912. Acceptance for mailing at special rate of postage provided for in the Act of February 28, 1925, 538, P. L. & R. Series III JULY, 1947 No. 59 Summer — >Q47 (Students in doorivay of temporary classroom building) Page 2 THE ATLANTA UNIVERSITY BULLETIN July, 1947 SfUiaa CalesvdaA CONVOCATION : January 2—Pastor Martin Nie- CONVOCATION : April 3—Rabbi Abraham Feinstein, inoeller of the Jesus Christ Church, Berlin, Ger¬ Mizpah Congregation, Chattanooga, Tennessee many RECITAL: April 3—Edwin Gerschefski, Pianist EO RUM: January 6-7—George L. P. Weaver, Execu¬ tive Secretary, National CIO Committee to Abol¬ RECI TAL: April 4—Robert ish Segregation Williams, Tenor EXHIBI T: April 6—Sixth Annual Exhibition of Paint¬ FORUM : January 15—Paul Styles, Regional Director, ings, Sculpture and Prints Labor Relations Board by Negro Artists LECTURE: April 14—Victor Bernstein, Author UNIVERSITY CENTER CONVOCATION: Janu¬ ary 26—President William Lloyd lines of Knox¬ ville College FORUM: April 16—Dr. Hilda Taba, Director, Inter¬ group Education in Cooperating Schools, American Council on Education CONVOCATION: January 30—Miss Ruth Seabury, Secretary of Missionary Education, American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions RECITAL: April 18—Camilla Williams, Soprano THE EDWIN STRAWBRIDGE BALLET: Febru¬ FORUM: April 30—Langston Hughes, Poet ary 1—“Pinocchio” THE UNIVERSITY PLAYERS: May 9-10—“Right FORUM: You Are” February 5—Dr. Kimball V oung, Chairman, Department of Sociology, Queens College EXHIBIT: May 11—Annual Student Exhibition RECITAL: Feb ruary 7—Carl Weinrich, Organist CONCERT: May 16—Twentieth Annual Concert by the LECTURE: February 10—Dr.