Potentials of Entrepreneurial Approaches in Addressing Global Societal Challenges: the Case of Fresh Water Supply

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hållbara Och Attraktiva Stationssamhällen

HÅLLBARA OCH ATTRAKTIVA STATIONSSAMHÄLLEN Titel: Hållbara och attraktiva stationssamhällen, HASS (populärvetenskaplig sammanfattning) Författare: Åsa Hult, Anders Roth och Sebastian Bäckström, IVL Svenska Miljöinstitutet, Camilla Stålstad, RISE Viktoria ICT, Julia Jonasson, RISE samt Maja Kovacs, Ida Röstlund och Lisa Bomble, Chalmers. Medel från: Vinnova, Västra Götalandsregionen, Ale kommun och Lerums kommun Layout: Ragnhild Berglund, IVL Svenska Miljöinstitutet Bild framsida: Pendelpoden, en mobilitetstjänst som testades inom projektet I rapporten hänvisas till bilagor med mer detaljerade resultat från studien. De kan laddas ner från projektets sida hos www.ivl.se. Rapportnummer: C318 ISBN-nr: 978-91-88787-61-3 Upplaga: Finns endast som PDF-fil för egen utskrift © IVL Svenska Miljöinstitutet 2018 IVL Svenska Miljöinstitutet AB, Box 210 60, 100 31 Stockholm Telefon 010-788 65 00 • www.ivl.se Rapporten har granskats och godkänts i enlighet med IVL:s ledningssystem SAMMANFATTNING Projektet Hållbara och attraktiva stationssamhällen (HASS) är ett utmanings drivet innovationsprojekt som utvecklat och testat lösningar som kan bidra till en mindre bilberoende livsstil i samhällen utanför storstäder. Stationssamhällena Lerum och Nödinge (i Ale belöningar kan få människor att ändra sina resvanor. kommun) strax utanför Göteborg har varit test- Vidare utvecklades en affärsmodell för plattformen arenor i projektet. 24 projektpartners från olika (appen) för lokala res- och transporttjänster. sektorer har deltagit; kommuner, regioner, I projektet har en medskapandeprocess använts, där forskningsorganisationer, fastighetsbolag, både projektparter och allmänhet har bjudits in att detaljhandel, banker, mäklare, företag inom tycka till och uttrycka sina behov. persontransport samt en it-plattforms leverantör. Parkeringsstudien, planeringsverktyget för Projektet tar sin utgångspunkt i två konkreta markexploatering samt själva projektprocessen politiska mål; öka byggandet i kommunerna och har varit till stor nytta för parterna. -

Invitation to Acquire Shares in Fortinova Fastigheter Ab (Publ)

INVITATION TO ACQUIRE SHARES IN FORTINOVA FASTIGHETER AB (PUBL) Distribution of this Prospectus and subscription of new shares are subject to restrictions in some jurisdictions, see “Important Information to Investors”. THE PROSPECTUS WAS APPROVED BY THE FINANCIAL SUPERVISORY Global Coordinator and Joint Bookrunner AUTHORITY ON 6 NOVEMBER 2020. The period of validity of the Prospectus expires on 6 November 2021. The obligation to provide supplements to the Prospectus in the event of new circumstances of significance, factual errors or material inaccuracies will not apply once the Prospectus is no longer valid. Retail Manager IMPORTANT INFORMATION TO INVESTORS This prospectus (the “Prospectus”) has been prepared in connection with the STABILIZATION offering to the public in Sweden of Class B shares in Fortinova Fastigheter In connection with the Offering, SEB may carry out transactions aimed at AB (publ) (a Swedish public limited company) (the “Offering”) and the listing supporting the market price of the shares at levels above those which might of the Class B shares for trading on Nasdaq First North Premier Growth Mar- otherwise prevail in the open market. Such stabilization transactions may ket. In the Prospectus, “Fortinova”, the “Company” or the “Group” refers to be effected on Nasdaq First North Premier Growth Market, in the over-the- Fortinova Fastigheter AB (publ), the group of which Fortinova Fastigheter counter market or otherwise, at any time during the period starting on the AB (publ) is the parent company, or a subsidiary of the Group, depending date of commencement of trading in the shares on Nasdaq First North Pre- on the context. -

Collaboration on Sustainable Urban Development in Mistra Urban Futures

Collaboration on sustainable urban development in Mistra Urban Futures 1 Contents The Gothenburg Region wants to contribute where research and practice meet .... 3 Highlights from the Gothenburg Region’s Mistra Urban Futures Network 2018....... 4 Urban Station Communities ............................................................................................ 6 Thematic Networks within Mistra Urban Futures ......................................................... 8 Ongoing Projects ............................................................................................................ 10 Mistra Urban Futures events during 2018 .................................................................. 12 Agenda 2030 .................................................................................................................. 14 WHAT IS MISTRA URBAN FUTURES? Mistra Urban Futures is an international research and knowledge centre for sustainable urban development. We develop and apply knowledge to promote accessible, green and fair cities. Co-production – jointly defining, developing and applying knowledge across different disciplines and subject areas from both research and practice – is our way of working. The centre was founded in and is managed from Gothenburg, but also has platforms in Skåne (southern Sweden), Stockholm, Sheffield-Manchester (United Kingdom), Kisumu (Kenya), and Cape Town (South Africa). www.mistraurbanfutures.org The Gothenburg Region (GR) consists of 13 municipalities The Gothenburg Region 2019. who have chosen -

Mobility Between European Regions Regional Mobility Systems for the People Mobireg 2 Index

Mobility between European regions Regional mobility systems for the people Mobireg 2 Index Introduction: . Regional governments and citizen mobility for study and work purposes Gianfranco Simoncini, Assessore regionale, Regione Toscana 1 . Criteria for transparency in the quality of the mobility between the Regions of Europe: describers of reception services 2 . Quality in inter-regional mobility, Xavier Farriols, Departament d’Educació, Generalitat de Catalunya 3 . Examples of regional plans for using ESF for inter-regional co-operation at European level: Regional Government of Tuscany, Giacomo Gambino, Regione Toscana 4 . The regional system of trans-national mobility Region of Tuscany- Directorate-General for Cultural and Education policy 5 . Catalan Regional Platform for Mobility: Policies for inter-regional cooperation. Planning and manage ment system for inter-regional mobility 6 . Mobility for study purposes in Region Västra Götaland Annexes 1 . Memorandum of Understanding between the Regional Government and the Regional Government with regard to developing a programme of mobility in lifelong learning . 2 . Programme for stage and exchange activities between the Departament d’Educació i Universitats de la Generalitat de Catalunya and Tuscany Regional Authority concerning professional training . 3 . Plan for the implementation of the Bilateral Agreement on mobility signed by Tuscany Regional Authority and the Generalitat de Catalunya . 4 . Programme for stage and exchange activities between the Region Västra Götaland and Tuscany Regional Authority concerning professional training . 5 . .Implementation Plan of the Bilateral agreement on mobility between Regione Toscana and Region Västra Götaland . Project Mobireg, Regional Mobility, financed by the European Commission- Official Journal 2006/C 194/10 Call for Proposals – DG EAC No 45/06 – Award of grants for the establishment and development of platforms and measures to promote and support the mobility of apprentices and other young people in initial vocational training (IVT) Agreement n . -

Idrottens Högsta Utmärkelse Till 212 Västgötar

1 (5) RF:s Förtjänsttecken i guld Sedan år 1910 har Riksidrottsförbundet utdelat förtjänsttecken i guld. RF:s förtjänsttecken är i första hand en utmärkelse som utdelas för förtjänstfullt ledarskap på förbundsnivå och utdelas vid Riksidrottsmötet som hålls vartannat år. Vederbörande skall inneha sitt SF:s eller DF:s högsta utmärkelse. Av sammanställning framgår att 233 st västgötar har mottagit RF:s förtjänsttecken genom åren. (Personer som är med på listan är de som är nominerade av Västergötlands Idrottsförbund) År 2015 Brink, Folke Lidköping Leijon, Börje Götene Svensson, Kent Tidaholm 2013 Arwidson, Bengt Vänersborg Coltén, Rune Tidaholm Ivarsson, Hans-Åke Tidaholm Oscarsson, Roland Herrljunga Sjöstrand, Per Vårgårda 2011 Andersson, Sven Skene Fäldt, Åke Örby Ingemarsson, Bengt Lidköping Svensson, Håkan Vara 2009 Hellberg, Sven-Eric Falköping Johansson, Kjell-Åke Falköping Karlström, Sören Skövde Knutson, Sven Ulricehamn Wahll, Gösta Tibro Wänerstig, Rolf Lidköping Mökander, Sven-Åke Alingsås 2007 Ferm, Ronny Karlsborg Svensson, Stefan Vara 2005 Alvarsson, Bengt-Rune Hjo Johansson, Assar Falköping Persson, Willy Mariestad Samuelsson, Nils Inge Vårgårda Wernmo, Stig Mullsjö 2003 Carlsson, Evert Falköping Dahlén, Curt-Olof Brämhult Jakobsson, Jan Tidaholm Källström, Roland Lidköping Påhlman, Bertil Skara Siljehult, Rune Hjo Turin, Peter Falköping Wassenius, Pentti Lilla Edet 2001 Cronholm, Gösta Tidaholm Einarsson, Göran Falköping Hartung, Marie Mariestad Högstedt, Lennart Mariestad Lindh, Ove Otterbäcken Peterson, S Gunnar Vänersborg -

Organizing Labour Market Integration of Foreign-Born Persons in the Gothenburg Metropolitan Area

Gothenburg Research Institute GRI-rapport 2018:3 Organizing Integration Organizing Labour Market Integration of Foreign-born Persons in the Gothenburg Metropolitan Area Andreas Diedrich & Hanna Hellgren © Gothenburg Research Institute All rights reserved. No part of this report may be repro- duced without the written permission from the publisher. Gothenburg Research Institute School of Business, Economics and Law at University of Gothenburg P.O. Box 600 SE-405 30 Göteborg Tel: +46 (0)31 - 786 54 13 Fax: +46 (0)31 - 786 56 19 e-mail: [email protected] gri.gu.se / gri-bloggen.se ISSN 1400-4801 Organizing Labour Market Integration of Foreign-born Persons in the Gothenburg Metropolitan Area Andreas Diedrich Associate Professor of Business Administration, School of Business, Economics and Law, University of Gothenburg Hanna Hellgren PhD. Student, School of Public Administration, University of Gothenburg Preface This report was compiled by Andreas Diedrich and Hanna Hellgren at the University of Gothenburg (Gothenburg Research Institute & School of Public Administration). The report also includes insights from other members of the “Organizing labour market in- tegration of foreign-born persons – theory and practice” research program: María José Zapata Campos, Vedran Omanovic, Patrik Zapata, Ester Barinaga, Barbara Czarniawska, Nanna Gillberg, Eva-Maria Jernsand, Helena Kraff and Henrietta Palmer. It was made possible with funding from FORTE, Stiftelsen för Ekonomiskt Forskning i Västsverige and Mistra Urban Futures (Gothenburg Platform). 3 Contents -

Landslide Risks in the Göta River Valley in a Changing Climate

Landslide risks in the Göta River valley in a changing climate Final report Part 2 - Mapping GÄU The Göta River investigation 2009 - 2011 Linköping 2012 The Göta River investigation Swedish Geotechnical Institute (SGI) Final report, Part 2 SE-581 93 Linköping, Sweden Order Information service, SGI Tel: +46 13 201804 Fax: +46 13 201914 E-mail: [email protected] Download the report on our website: www.swedgeo.se Photos on the cover © SGI Landslide risks in the Göta River valley in a changing climate Final report Part 2 - Mapping Linköping 2012 4 Landslide risks in the Göta älv valley in a changing climate 5 Preface In 2008, the Swedish Government commissioned the Swedish Geotechnical Institute (SGI) to con- duct a mapping of the risks for landslides along the entire river Göta älv (hereinafter called the Gö- ta River) - risks resulting from the increased flow in the river that would be brought about by cli- mate change (M2008/4694/A). The investigation has been conducted during the period 2009-2011. The date of the final report has, following a government decision (17/11/2011), been postponed until 30 March 2012. The assignment has involved a comprehensive risk analysis incorporating calculations of the prob- ability of landslides and evaluation of the consequences that could arise from such incidents. By identifying the various areas at risk, an assessment has been made of locations where geotechnical stabilising measures may be necessary. An overall cost assessment of the geotechnical aspects of the stabilising measures has been conducted in the areas with a high landslide risk. -

Mapping and Interpretation of Background Levels of Lead

Mapping and Interpretation of Background Levels of Lead Concentrations in Natural Soils A case study of Ale municipality Master of Science Thesis in the Master’s Programme Infrastructure and Environmental Engineering PETRA ALMQVIST, ROBERT ANDERSON Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Division of GeoEngineering CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Göteborg, Sweden 2014 Master’s Thesis 2014:41 MASTER’S THESIS 2014:41 Mapping and Interpretation of Background Levels of Lead Concentrations in Natural Soils A case study of Ale municipality Master of Science Thesis in the Master’s Programme Infrastructure and Environmental Engineering PETRA ALMQVIST, ROBERT ANDERSON Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Division of GeoEngineering CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Göteborg, Sweden 2014 Mapping and Interpretation of Background Levels of Lead Concentrations in Natural Soils - A case study of Ale municipality Master of Science Thesis in the Master’s Programme Infrastructure and Environmental Engineering P. ALMQVIST, R. ANDERSON © P. ALMQVIST, R. ANDERSON, 2014 Examensarbete / Institutionen för bygg- och miljöteknik, Chalmers tekniska högskola 2014:41 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Division of GeoEngineering Chalmers University of Technology SE-412 96 Göteborg Sweden Telephone: + 46 (0)31-772 1000 Cover: Interpolation map for the Nödinge profile and characteristic forest of Ale. Photo: Petra Almqvist Name of the printers / Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Göteborg, Sweden 2014 Mapping and -

An Investment Strategy Framework for Rental Real Estate

An Investment Strategy Framework for Rental Real Estate An Analysis of Potential Yields and Strategic Options in Western Sweden Master of Science Thesis in the Master Degree Programme, Management and Economcis of Innovation FREDRIK HÄRENSTAM JOHAN THUNGREN LUNDH JAKOB UNFORS Department of Technology Management and Economics Division of Innovation Engineering and Management CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Göteborg, Sweden, 2012 Report No. E 2012:086 MASTER’S THESIS E 2012:086 An Investment Strategy Framework for Rental Real Estate An Analysis of Potential Yields and Strategic Options in Western Sweden FREDRIK HÄRENSTAM JOHAN THUNGREN LUNDH JAKOB UNFORS Tutor, Chalmers: Jonas Hjerpe Tutor, company: Fredrik Svensson Department of Technology Management and Economics Division of Innovation Engineering and Management CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Göteborg, Sweden 2012 An Investment Strategy Framework for Rental Real Estate An Analysis of Potential Yields and Strategic Options in Western Sweden Fredrik Härenstam, Johan Thungren Lundh, and Jakob Unfors © Fredrik Härenstam, Johan Thungren Lundh, Jakob Unfors, 2012 Master’s Thesis E 2012:086 Department of Technology Management and Economics Division of Innovation Engineering and Management Chalmers University of Technology SE-412 96 Göteborg, Sweden Telephone: + 46 (0)31-772 1000 Chalmers Reproservice Göteborg, Sweden 2012 Preface We would like to thank both Fredrik Svensson and Jonas Hjerpe in providing insightful guidance throughout the course of this project. Their support helped structure and push the work forward. They were also instrumental in gathering expert opinion to create a forum of real estate investment insight in which our work could be vented and tested along the way. We would also like to thank all respondents for their participation. -

E20 Byggs Ut För Ökad Trafiksäkerhet Och Framkomlighet

E20 byggs ut för ökad trafiksäkerhet och framkomlighet 2010-07 I juni 2009 invigdes ny motorväg på en 12 km lång sträcka förbi Götene. Sträckan mellan Alingsås och Vårgårda är idag ej mötesseparerad landsväg. Etappen finns med i nationella planen för 2010-2021 och ska byggas om till motorväg. Skåre Karlstad Arboga Grums Skoghall Karlskoga Kristinehamn Örebro Mötesseparerat är bäst Varierande standard på E20 Degerfors Säffle Kumla Åmål Hallsberg Vingåker Väg E20 ingår i det nationella stamvägnätet och har stor Som framgår av kartan här intill är en stor del av E20Strömstad Laxå 50 ± genom Västra Götaland ej mötesseparerad väg. Det le- ³ Askersund betydelse för näringslivets transporter och arbetspend- 26 ± ³ der till sämre trafiksäkerhet, köbildningar och lägre 49 ± lingen i regionen. Vägen är även viktig för internationell ³ Mellerud Mariestad Töreboda godstrafik, till exempel från Göteborgs hamn till Berg- hastighetsgränser. Finspång 45 ± ³ E20 ± slagen, Mälardalen, Dalarna och södra Norrland. E20 ³ 50 ± ³ Skärblacka Götene Karlsborg Motala Trafikverket samarbetar med Västra Götalandsregio- Lidköping Munkedal är också en strategisk förbindelse mellan Sveriges två Ljungsbro 32 ± ³ nen och Skaraborgs kommunalförbund om den stra- Vadstena största städer, Stockholm och Göteborg. Vänersborg Malmslätt 49 Tibro ± 44 Skara ³ ± Skövde ³ 50 Linköping ± Uddevalla ³ 44 ± ³ 47 ± tegiska inriktningen för att bygga ut E20 genom Väs- Lysekil ³ Mjölby E6 Trollhättan ± ³ Hjo Vara 26 ± ³ E4 ± På nuvarande väg E20 genom Västra Götaland finns tra Götaland för att ge bättre framkomlighet och ökad ³ Falköping Åtvidaberg Lilla Edet 42 ± trafiksäkerhet. ³ Tidaholm dock betydande problem med såväl trafiksäkerhet som Herrljunga 46 ± Stenungsund ³ 45 ± ³ Vårgårda framkomlighet på en del etapper. Trafikverket planerar E20 Tranås ± ³ Älvängen Kisa 32 ± ³ I den här broschyren kan Du läsa om nuvarande stan- Kungälv Alingsås och genomför åtgärder på många etapper för att lösa Habo Mullsjö 42 ± Gråbo ³ dard på E20 genom Västra Götaland, vilka åtgärder som Bankeryd dessa problem. -

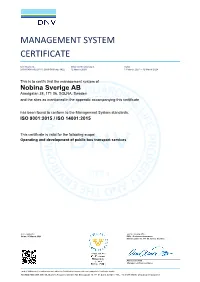

MSC Certificate

MANAGEMENT SYSTEM CERTIFICATE Certificate no.: Initial certification date: Valid: 2009-SKM-AQ-2710 / 2009-SKM-AE-1422 12 March 2009 13 March 2021 – 12 March 2024 This is to certify that the management system of Nobina Sverige AB Armégatan 38, 171 06, SOLNA, Sweden and the sites as mentioned in the appendix accompanying this certificate has been found to conform to the Management System standards: ISO 9001:2015 / ISO 14001:2015 This certificate is valid for the following scope: Operating and development of public bus transport services Place and date: For the issuing office: Solna, 05 March 2021 DNV - Business Assurance Elektrogatan 10, 171 54, Solna, Sweden Ann-Louise Pått Management Representative Lack of fulfilment of conditions as set out in the Certification Agreement may render this Certificate invalid. ACCREDITED UNIT: DNV GL Business Assurance Sweden AB, Elektrogatan 10, 171 54 Solna, Sweden - TEL: +46 8 587 940 00. www.dnvgl.se/assurance Certificate no.: 2009-SKM-AQ-2710 / 2009-SKM-AE-1422 Place and date: Solna, 05 March 2021 Appendix to Certificate Nobina Sverige AB Locations included in the certification are as follows: Site Name Site Address Site Scope Nobina Sverige AB Armégatan 38, 171 06, SOLNA, Sweden Operating and development of public bus transport services Nobina Sverige AB, Central trafikledning Armégatan 38,171 06, SOLNA, Sweden Operating and development of public bus Mitt Solna transport services Nobina Sverige AB, Central trafikledning Kruthusgatan 17, 411 04, GÖTEBORG, Operating and development of public bus Väst -

Kommuninvest Green Bonds Impact Report

Kommuninvest Green Bonds Impact Report, December 2016 Report on 81 Swedish local government investment projects financed by Kommuninvest Green Bonds as of year-end 2016. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), officially known as Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, are a set of seventeen aspirational global goals, with 169 specific targets, adopted through a United Nations resolution in September 2015. The Kom- muninvest Green Bonds Framework addresses six of the SDGs, as presented below. • #6 Clean Water and Sanitation • #7 Affordable and Clean Energy • #9 Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure • #11 Sustainable Cities and Communities • #13 Climate Action • #15 Life on Land About Kommuninvest Kommuninvest is a Swedish municipal cooperation set up in 1986 to provide cost-efficient and sustainable financing for local government investments in housing, infrastructure, schools, hos- pitals etc. The cooperation comprises 288 out of Sweden’s 310 local governments, of which 277 municipalities and 11 county councils/regions. Kommuninvest is the largest lender to the Swedish local government sector and the sixth largest credit institution in Sweden. At year-end 2016, total assets were SEK 362 billion, with a loan portfolio of SEK 277 billion. The head office is located in Örebro. kommuninvest.se Cover page: iStock ISBN: 978-91-983081-2-9 1 Foreword by the Kommuninvest Green Bonds Environmental Committee Dear reader, It gives us great pleasure to provide you with cal governments with access to green financing this first green bonds impact report, follow- for green investments. To that end, we deem ing the introduction of Kommuninvest Green the launch of the framework a success.