Ocular Coloboma: a Reassessment in the Age of Molecular Neuroscience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National Economic Burden of Rare Disease Study February 2021

Acknowledgements This study was sponsored by the EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases and made possible through the collaborative efforts of the national rare disease community and key stakeholders. The EveryLife Foundation thanks all those who shared their expertise and insights to provide invaluable input to the study including: the Lewin Group, the EveryLife Community Congress membership, the Technical Advisory Group for this study, leadership from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN), the Little Hercules Foundation, the Rare Disease Legislative Advocates (RDLA) Advisory Committee, SmithSolve, and our study funders. Most especially, we thank the members of our rare disease patient and caregiver community who participated in this effort and have helped to transform their lived experience into quantifiable data. LEWIN GROUP PROJECT STAFF Grace Yang, MPA, MA, Vice President Inna Cintina, PhD, Senior Consultant Matt Zhou, BS, Research Consultant Daniel Emont, MPH, Research Consultant Janice Lin, BS, Consultant Samuel Kallman, BA, BS, Research Consultant EVERYLIFE FOUNDATION PROJECT STAFF Annie Kennedy, BS, Chief of Policy and Advocacy Julia Jenkins, BA, Executive Director Jamie Sullivan, MPH, Director of Policy TECHNICAL ADVISORY GROUP Annie Kennedy, BS, Chief of Policy & Advocacy, EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases Anne Pariser, MD, Director, Office of Rare Diseases Research, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health Elisabeth M. Oehrlein, PhD, MS, Senior Director, Research and Programs, National Health Council Christina Hartman, Senior Director of Advocacy, The Assistance Fund Kathleen Stratton, National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) Steve Silvestri, Director, Government Affairs, Neurocrine Biosciences Inc. -

Analysis of Gene Expression Data for Gene Ontology

ANALYSIS OF GENE EXPRESSION DATA FOR GENE ONTOLOGY BASED PROTEIN FUNCTION PREDICTION A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Robert Daniel Macholan May 2011 ANALYSIS OF GENE EXPRESSION DATA FOR GENE ONTOLOGY BASED PROTEIN FUNCTION PREDICTION Robert Daniel Macholan Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Department Chair Dr. Zhong-Hui Duan Dr. Chien-Chung Chan _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College Dr. Chien-Chung Chan Dr. Chand K. Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Yingcai Xiao Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ Date ii ABSTRACT A tremendous increase in genomic data has encouraged biologists to turn to bioinformatics in order to assist in its interpretation and processing. One of the present challenges that need to be overcome in order to understand this data more completely is the development of a reliable method to accurately predict the function of a protein from its genomic information. This study focuses on developing an effective algorithm for protein function prediction. The algorithm is based on proteins that have similar expression patterns. The similarity of the expression data is determined using a novel measure, the slope matrix. The slope matrix introduces a normalized method for the comparison of expression levels throughout a proteome. The algorithm is tested using real microarray gene expression data. Their functions are characterized using gene ontology annotations. The results of the case study indicate the protein function prediction algorithm developed is comparable to the prediction algorithms that are based on the annotations of homologous proteins. -

Molecular and Physiological Basis for Hair Loss in Near Naked Hairless and Oak Ridge Rhino-Like Mouse Models: Tracking the Role of the Hairless Gene

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2006 Molecular and Physiological Basis for Hair Loss in Near Naked Hairless and Oak Ridge Rhino-like Mouse Models: Tracking the Role of the Hairless Gene Yutao Liu University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Liu, Yutao, "Molecular and Physiological Basis for Hair Loss in Near Naked Hairless and Oak Ridge Rhino- like Mouse Models: Tracking the Role of the Hairless Gene. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2006. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1824 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Yutao Liu entitled "Molecular and Physiological Basis for Hair Loss in Near Naked Hairless and Oak Ridge Rhino-like Mouse Models: Tracking the Role of the Hairless Gene." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Life Sciences. Brynn H. Voy, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Naima Moustaid-Moussa, Yisong Wang, Rogert Hettich Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

Paternal Factors and Schizophrenia Risk: De Novo Mutations and Imprinting

Paternal Factors and Schizophrenia Risk: De Novo Mutations and Imprinting by Dolores Malaspina Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/schizophreniabulletin/article/27/3/379/1835092 by guest on 23 September 2021 Abstract (Impagnatiello et al. 1998; Kao et al. 1998), but there is no consensus that any particular gene plays a meaning- There is a strong genetic component for schizophrenia ful role in the etiology of schizophrenia (Hyman 2000). risk, but it is unclear how the illness is maintained in Some of the obstacles in genetic research in schiz- the population given the significantly reduced fertility ophrenia are those of any complex disorder, and include of those with the disorder. One possibility is that new incomplete penetrance, polygenic interaction (epista- mutations occur in schizophrenia vulnerability genes. sis), diagnostic instability, and variable expressivity. If so, then those with schizophrenia may have older Schizophrenia also does not show a clear Mendelian fathers, because advancing paternal age is the major inheritance pattern, although segregation analyses have source of new mutations in humans. This review variably supported dominant, recessive, additive, sex- describes several neurodevelopmental disorders that linked, and oligogenic inheritance (Book 1953; Slater have been associated with de novo mutations in the 1958; Garrone 1962; Elston and Campbell 1970; Slater paternal germ line and reviews data linking increased and Cowie 1971; Karlsson 1972; Stewart et al. 1980; schizophrenia risk with older fathers. Several genetic Risch 1990a, 1990fc; reviewed by Kendler and Diehl mechanisms that could explain this association are 1993). Furthermore, both nonallelic (Kaufmann et al. proposed, including paternal germ line mutations, 1998) and etiologic heterogeneity (Malaspina et al. -

Bhagwan Moorjani, MD, FAAP, FAAN • Requires Knowledge of Normal CNS Developmental (I.E

1/16/2012 Neuroimaging in Childhood • Neuroimaging issues are distinct from Pediatric Neuroimaging in adults Neurometabolic-degenerative disorder • Sedation/anesthesia and Epilepsy • Motion artifacts Bhagwan Moorjani, MD, FAAP, FAAN • Requires knowledge of normal CNS developmental (i.e. myelin maturation) • Contrast media • Parental anxiety Diagnostic Approach Neuroimaging in Epilepsy • Age of onset • Peak incidence in childhood • Static vs Progressive • Occurs as a co-morbid condition in many – Look for treatable causes pediatric disorders (birth injury, – Do not overlook abuse, Manchausen if all is negative dysmorphism, chromosomal anomalies, • Phenotype presence (syndromic, HC, NCS, developmental delays/regression) systemic involvement) • Predominant symptom (epilepsy, DD, • Many neurologic disorders in children weakness/motor, psychomotor regression, have the same chief complaint cognitive/dementia) 1 1/16/2012 Congenital Malformation • Characterized by their anatomic features • Broad categories: based on embryogenesis – Stage 1: Dorsal Induction: Formation and closure of the neural tube. (Weeks 3-4) – Stage 2: Ventral Induction: Formation of the brain segments and face. (Weeks 5-10) – Stage 3: Migration and Histogenesis: (Months 2-5) – Stage 4: Myelination: (5-15 months; matures by 3 years) Dandy Walker Malformation Dandy walker • Criteria: – high position of tentorium – dysgenesis/agenesis of vermis – cystic dilatation of fourth ventricle • commonly associated features: – hypoplasia of cerebellum – scalloping of inner table of occipital bone • associated abnormalities: – hydrocephalus 75% – dysgenesis of corpus callosum 25% – heterotropia 10% 2 1/16/2012 Etiology of Epilepsy: Developmental and Genetic Classification of Gray Matter Heterotropia Cortical Dysplasia 1. Secondary to abnormal neuronal and • displaced masses of nerve cells • Subependymal glial proliferation/apoptosis (gray matter) heterotropia (most • most common: small nest common) 2. -

Primate Specific Retrotransposons, Svas, in the Evolution of Networks That Alter Brain Function

Title: Primate specific retrotransposons, SVAs, in the evolution of networks that alter brain function. Olga Vasieva1*, Sultan Cetiner1, Abigail Savage2, Gerald G. Schumann3, Vivien J Bubb2, John P Quinn2*, 1 Institute of Integrative Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 7ZB, U.K 2 Department of Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology, Institute of Translational Medicine, The University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 3BX, UK 3 Division of Medical Biotechnology, Paul-Ehrlich-Institut, Langen, D-63225 Germany *. Corresponding author Olga Vasieva: Institute of Integrative Biology, Department of Comparative genomics, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 7ZB, [email protected] ; Tel: (+44) 151 795 4456; FAX:(+44) 151 795 4406 John Quinn: Department of Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology, Institute of Translational Medicine, The University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 3BX, UK, [email protected]; Tel: (+44) 151 794 5498. Key words: SVA, trans-mobilisation, behaviour, brain, evolution, psychiatric disorders 1 Abstract The hominid-specific non-LTR retrotransposon termed SINE–VNTR–Alu (SVA) is the youngest of the transposable elements in the human genome. The propagation of the most ancient SVA type A took place about 13.5 Myrs ago, and the youngest SVA types appeared in the human genome after the chimpanzee divergence. Functional enrichment analysis of genes associated with SVA insertions demonstrated their strong link to multiple ontological categories attributed to brain function and the disorders. SVA types that expanded their presence in the human genome at different stages of hominoid life history were also associated with progressively evolving behavioural features that indicated a potential impact of SVA propagation on a cognitive ability of a modern human. -

Mutation in Genes FBN1, AKT1, and LMNA: Marfan Syndrome, Proteus Syndrome, and Progeria Share Common Systemic Involvement

Review Mutation in Genes FBN1, AKT1, and LMNA: Marfan Syndrome, Proteus Syndrome, and Progeria Share Common Systemic Involvement Tonmoy Biswas.1 Abstract Genetic mutations are becoming more deleterious day by day. Mutations of Genes named FBN1, AKT1, LMNA result specific protein malfunction that in turn commonly cause Marfan syndrome, Proteus syndrome, and Progeria, respectively. Articles about these conditions have been reviewed in PubMed and Google scholar with a view to finding relevant clinical features. Precise keywords have been used in search for systemic involvement of FBN1, AKT1, and LMNA gene mutations. It has been found that Marfan syndrome, Proteus syndrome, and Progeria commonly affected musculo-skeletal system, cardiovascular system, eye, and nervous system. Not only all of them shared identical systemic involvement, but also caused several very specific anomalies in various parts of the body. In spite of having some individual signs and symptoms, the mutual manifestations were worth mentio- ning. Moreover, all the features of the mutations of all three responsible genes had been co-related and systemically mentioned in this review. There can be some mutual properties of the genes FBN1, AKT1, and LMNA or in their corresponding proteins that result in the same presentations. This study may progress vision of knowledge regarding risk factors, patho-physiology, and management of these conditions, and relation to other mutations. Keywords: Genetic mutation; Marfan syndrome; Proteus syndrome; Progeria; Gene FBN1; Gene AKT1; Gene LMNA; Musculo-skeletal system; Cardiovascular system; Eye; Nervous system (Source: MeSH, NLM). Introduction Records in human mutation databases are increasing day by 5 About the author: Tonmoy The haploid human genome consists of 3 billion nucleotides day. -

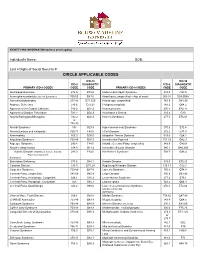

Circle Applicable Codes

IDENTIFYING INFORMATION (please print legibly) Individual’s Name: DOB: Last 4 Digits of Social Security #: CIRCLE APPLICABLE CODES ICD-10 ICD-10 ICD-9 DIAGNOSTIC ICD-9 DIAGNOSTIC PRIMARY ICD-9 CODES CODE CODE PRIMARY ICD-9 CODES CODE CODE Abetalipoproteinemia 272.5 E78.6 Hallervorden-Spatz Syndrome 333.0 G23.0 Acrocephalosyndactyly (Apert’s Syndrome) 755.55 Q87.0 Head Injury, unspecified – Age of onset: 959.01 S09.90XA Adrenaleukodystrophy 277.86 E71.529 Hemiplegia, unspecified 342.9 G81.90 Arginase Deficiency 270.6 E72.21 Holoprosencephaly 742.2 Q04.2 Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum 742.2 Q04.3 Homocystinuria 270.4 E72.11 Agenesis of Septum Pellucidum 742.2 Q04.3 Huntington’s Chorea 333.4 G10 Argyria/Pachygyria/Microgyria 742.2 Q04.3 Hurler’s Syndrome 277.5 E76.01 or 758.33 Aicardi Syndrome 333 G23.8 Hyperammonemia Syndrome 270.6 E72.4 Alcohol Embryo and Fetopathy 760.71 F84.5 I-Cell Disease 272.2 E77.0 Anencephaly 655.0 Q00.0 Idiopathic Torsion Dystonia 333.6 G24.1 Angelman Syndrome 759.89 Q93.5 Incontinentia Pigmenti 757.33 Q82.3 Asperger Syndrome 299.8 F84.5 Infantile Cerebral Palsy, unspecified 343.9 G80.9 Ataxia-Telangiectasia 334.8 G11.3 Intractable Seizure Disorder 345.1 G40.309 Autistic Disorder (Childhood Autism, Infantile 299.0 F84.0 Klinefelter’s Syndrome 758.7 Q98.4 Psychosis, Kanner’s Syndrome) Biotinidase Deficiency 277.6 D84.1 Krabbe Disease 333.0 E75.23 Canavan Disease 330.0 E75.29 Kugelberg-Welander Disease 335.11 G12.1 Carpenter Syndrome 759.89 Q87.0 Larsen’s Syndrome 755.8 Q74.8 Cerebral Palsy, unspecified 343.69 G80.9 -

![Downloaded from [266]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7352/downloaded-from-266-347352.webp)

Downloaded from [266]

Patterns of DNA methylation on the human X chromosome and use in analyzing X-chromosome inactivation by Allison Marie Cotton B.Sc., The University of Guelph, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Medical Genetics) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) January 2012 © Allison Marie Cotton, 2012 Abstract The process of X-chromosome inactivation achieves dosage compensation between mammalian males and females. In females one X chromosome is transcriptionally silenced through a variety of epigenetic modifications including DNA methylation. Most X-linked genes are subject to X-chromosome inactivation and only expressed from the active X chromosome. On the inactive X chromosome, the CpG island promoters of genes subject to X-chromosome inactivation are methylated in their promoter regions, while genes which escape from X- chromosome inactivation have unmethylated CpG island promoters on both the active and inactive X chromosomes. The first objective of this thesis was to determine if the DNA methylation of CpG island promoters could be used to accurately predict X chromosome inactivation status. The second objective was to use DNA methylation to predict X-chromosome inactivation status in a variety of tissues. A comparison of blood, muscle, kidney and neural tissues revealed tissue-specific X-chromosome inactivation, in which 12% of genes escaped from X-chromosome inactivation in some, but not all, tissues. X-linked DNA methylation analysis of placental tissues predicted four times higher escape from X-chromosome inactivation than in any other tissue. Despite the hypomethylation of repetitive elements on both the X chromosome and the autosomes, no changes were detected in the frequency or intensity of placental Cot-1 holes. -

Sema4 Noninvasive Prenatal Select

Sema4 Noninvasive Prenatal Select Noninvasive prenatal testing with targeted genome counting 2 Autosomal trisomies 5 Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) 6 Trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome) 7 Trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome) 8 Trisomy 16 9 Trisomy 22 9 Trisomy 15 10 Sex chromosome aneuploidies 12 Monosomy X (Turner syndrome) 13 XXX (Trisomy X) 14 XXY (Klinefelter syndrome) 14 XYY 15 Microdeletions 17 22q11.2 deletion 18 1p36 deletion 20 4p16 deletion (Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome) 20 5p15 deletion (Cri-du-chat syndrome) 22 15q11.2-q13 deletion (Angelman syndrome) 22 15q11.2-q13 deletion (Prader-Willi syndrome) 24 11q23 deletion (Jacobsen Syndrome) 25 8q24 deletion (Langer-Giedion syndrome) 26 Turnaround time 27 Specimen and shipping requirements 27 2 Noninvasive prenatal testing with targeted genome counting Sema4’s Noninvasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT)- Targeted Genome Counting analyzes genetic information of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) through a simple maternal blood draw to determine the risk for common aneuploidies, sex chromosomal abnormalities, and microdeletions, in addition to fetal gender, as early as nine weeks gestation. The test uses paired-end next-generation sequencing technology to provide higher depth across targeted regions. It also uses a laboratory-specific statistical model to help reduce false positive and false negative rates. The test can be offered to all women with singleton, twins and triplet pregnancies, including egg donor. The conditions offered are shown in below tables. For multiple gestation pregnancies, screening of three conditions -

Level Estimates of Maternal Smoking and Nicotine Replacement Therapy During Pregnancy

Using primary care data to assess population- level estimates of maternal smoking and nicotine replacement therapy during pregnancy Nafeesa Nooruddin Dhalwani BSc MSc Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 ABSTRACT Background: Smoking in pregnancy is the most significant preventable cause of poor health outcomes for women and their babies and, therefore, is a major public health concern. In the UK there is a wide range of interventions and support for pregnant women who want to quit. One of these is nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) which has been widely available for retail purchase and prescribing to pregnant women since 2005. However, measures of NRT prescribing in pregnant women are scarce. These measures are vital to assess its usefulness in smoking cessation during pregnancy at a population level. Furthermore, evidence of NRT safety in pregnancy for the mother and child’s health so far is nebulous, with existing studies being small or using retrospectively reported exposures. Aims and Objectives: The main aim of this work was to assess population- level estimates of maternal smoking and NRT prescribing in pregnancy and the safety of NRT for both the mother and the child in the UK. Currently, the only population-level data on UK maternal smoking are from repeated cross-sectional surveys or routinely collected maternity data during pregnancy or at delivery. These obtain information at one point in time, and there are no population-level data on NRT use available. As a novel approach, therefore, this thesis used the routinely collected primary care data that are currently available for approximately 6% of the UK population and provide longitudinal/prospectively recorded information throughout pregnancy. -

MECHANISMS in ENDOCRINOLOGY: Novel Genetic Causes of Short Stature

J M Wit and others Genetics of short stature 174:4 R145–R173 Review MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY Novel genetic causes of short stature 1 1 2 2 Jan M Wit , Wilma Oostdijk , Monique Losekoot , Hermine A van Duyvenvoorde , Correspondence Claudia A L Ruivenkamp2 and Sarina G Kant2 should be addressed to J M Wit Departments of 1Paediatrics and 2Clinical Genetics, Leiden University Medical Center, PO Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, Email The Netherlands [email protected] Abstract The fast technological development, particularly single nucleotide polymorphism array, array-comparative genomic hybridization, and whole exome sequencing, has led to the discovery of many novel genetic causes of growth failure. In this review we discuss a selection of these, according to a diagnostic classification centred on the epiphyseal growth plate. We successively discuss disorders in hormone signalling, paracrine factors, matrix molecules, intracellular pathways, and fundamental cellular processes, followed by chromosomal aberrations including copy number variants (CNVs) and imprinting disorders associated with short stature. Many novel causes of GH deficiency (GHD) as part of combined pituitary hormone deficiency have been uncovered. The most frequent genetic causes of isolated GHD are GH1 and GHRHR defects, but several novel causes have recently been found, such as GHSR, RNPC3, and IFT172 mutations. Besides well-defined causes of GH insensitivity (GHR, STAT5B, IGFALS, IGF1 defects), disorders of NFkB signalling, STAT3 and IGF2 have recently been discovered. Heterozygous IGF1R defects are a relatively frequent cause of prenatal and postnatal growth retardation. TRHA mutations cause a syndromic form of short stature with elevated T3/T4 ratio. Disorders of signalling of various paracrine factors (FGFs, BMPs, WNTs, PTHrP/IHH, and CNP/NPR2) or genetic defects affecting cartilage extracellular matrix usually cause disproportionate short stature.