Bhagwan Moorjani, MD, FAAP, FAAN • Requires Knowledge of Normal CNS Developmental (I.E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paternal Factors and Schizophrenia Risk: De Novo Mutations and Imprinting

Paternal Factors and Schizophrenia Risk: De Novo Mutations and Imprinting by Dolores Malaspina Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/schizophreniabulletin/article/27/3/379/1835092 by guest on 23 September 2021 Abstract (Impagnatiello et al. 1998; Kao et al. 1998), but there is no consensus that any particular gene plays a meaning- There is a strong genetic component for schizophrenia ful role in the etiology of schizophrenia (Hyman 2000). risk, but it is unclear how the illness is maintained in Some of the obstacles in genetic research in schiz- the population given the significantly reduced fertility ophrenia are those of any complex disorder, and include of those with the disorder. One possibility is that new incomplete penetrance, polygenic interaction (epista- mutations occur in schizophrenia vulnerability genes. sis), diagnostic instability, and variable expressivity. If so, then those with schizophrenia may have older Schizophrenia also does not show a clear Mendelian fathers, because advancing paternal age is the major inheritance pattern, although segregation analyses have source of new mutations in humans. This review variably supported dominant, recessive, additive, sex- describes several neurodevelopmental disorders that linked, and oligogenic inheritance (Book 1953; Slater have been associated with de novo mutations in the 1958; Garrone 1962; Elston and Campbell 1970; Slater paternal germ line and reviews data linking increased and Cowie 1971; Karlsson 1972; Stewart et al. 1980; schizophrenia risk with older fathers. Several genetic Risch 1990a, 1990fc; reviewed by Kendler and Diehl mechanisms that could explain this association are 1993). Furthermore, both nonallelic (Kaufmann et al. proposed, including paternal germ line mutations, 1998) and etiologic heterogeneity (Malaspina et al. -

Mutation in Genes FBN1, AKT1, and LMNA: Marfan Syndrome, Proteus Syndrome, and Progeria Share Common Systemic Involvement

Review Mutation in Genes FBN1, AKT1, and LMNA: Marfan Syndrome, Proteus Syndrome, and Progeria Share Common Systemic Involvement Tonmoy Biswas.1 Abstract Genetic mutations are becoming more deleterious day by day. Mutations of Genes named FBN1, AKT1, LMNA result specific protein malfunction that in turn commonly cause Marfan syndrome, Proteus syndrome, and Progeria, respectively. Articles about these conditions have been reviewed in PubMed and Google scholar with a view to finding relevant clinical features. Precise keywords have been used in search for systemic involvement of FBN1, AKT1, and LMNA gene mutations. It has been found that Marfan syndrome, Proteus syndrome, and Progeria commonly affected musculo-skeletal system, cardiovascular system, eye, and nervous system. Not only all of them shared identical systemic involvement, but also caused several very specific anomalies in various parts of the body. In spite of having some individual signs and symptoms, the mutual manifestations were worth mentio- ning. Moreover, all the features of the mutations of all three responsible genes had been co-related and systemically mentioned in this review. There can be some mutual properties of the genes FBN1, AKT1, and LMNA or in their corresponding proteins that result in the same presentations. This study may progress vision of knowledge regarding risk factors, patho-physiology, and management of these conditions, and relation to other mutations. Keywords: Genetic mutation; Marfan syndrome; Proteus syndrome; Progeria; Gene FBN1; Gene AKT1; Gene LMNA; Musculo-skeletal system; Cardiovascular system; Eye; Nervous system (Source: MeSH, NLM). Introduction Records in human mutation databases are increasing day by 5 About the author: Tonmoy The haploid human genome consists of 3 billion nucleotides day. -

Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly

277 Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly KellenD.Winden,MD,PhD1 Christopher J. Yuskaitis, MD, PhD1 Annapurna Poduri, MD, MPH2 1 Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Address for correspondence Annapurna Poduri, Epilepsy Genetics Massachusetts Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Electrophysiology, 2 Epilepsy Genetics Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Department of Neurology, Fegan 9, Boston Children’s Hospital, 300 Electrophysiology, Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115 Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (e-mail: [email protected]). Semin Neurol 2015;35:277–287. Abstract Megalencephaly is a developmental disorder characterized by brain overgrowth secondary to increased size and/or numbers of neurons and glia. These disorders can be divided into metabolic and developmental categories based on their molecular etiologies. Metabolic megalencephalies are mostly caused by genetic defects in cellular metabolism, whereas developmental megalencephalies have recently been shown to be caused by alterations in signaling pathways that regulate neuronal replication, growth, and migration. These disorders often lead to epilepsy, developmental disabilities, and Keywords behavioral problems; specific disorders have associations with overgrowth or abnor- ► megalencephaly malities in other tissues. The molecular underpinnings of many of these disorders are ► hemimegalencephaly now understood, providing insight into how dysregulation of critical pathways leads to ► -

Level Estimates of Maternal Smoking and Nicotine Replacement Therapy During Pregnancy

Using primary care data to assess population- level estimates of maternal smoking and nicotine replacement therapy during pregnancy Nafeesa Nooruddin Dhalwani BSc MSc Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 ABSTRACT Background: Smoking in pregnancy is the most significant preventable cause of poor health outcomes for women and their babies and, therefore, is a major public health concern. In the UK there is a wide range of interventions and support for pregnant women who want to quit. One of these is nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) which has been widely available for retail purchase and prescribing to pregnant women since 2005. However, measures of NRT prescribing in pregnant women are scarce. These measures are vital to assess its usefulness in smoking cessation during pregnancy at a population level. Furthermore, evidence of NRT safety in pregnancy for the mother and child’s health so far is nebulous, with existing studies being small or using retrospectively reported exposures. Aims and Objectives: The main aim of this work was to assess population- level estimates of maternal smoking and NRT prescribing in pregnancy and the safety of NRT for both the mother and the child in the UK. Currently, the only population-level data on UK maternal smoking are from repeated cross-sectional surveys or routinely collected maternity data during pregnancy or at delivery. These obtain information at one point in time, and there are no population-level data on NRT use available. As a novel approach, therefore, this thesis used the routinely collected primary care data that are currently available for approximately 6% of the UK population and provide longitudinal/prospectively recorded information throughout pregnancy. -

Classification of Congenital Abnormalities of the CNS

315 Classification of Congenital Abnormalities of the CNS M. S. van der Knaap1 A classification of congenital cerebral, cerebellar, and spinal malformations is pre J . Valk2 sented with a view to its practical application in neuroradiology. The classification is based on the MR appearance of the morphologic abnormalities, arranged according to the embryologic time the derangement occurred. The normal embryology of the brain is briefly reviewed, and comments are made to explain the classification. MR images illustrating each subset of abnormalities are presented. During the last few years, MR imaging has proved to be a diagnostic tool of major importance in children with congenital malformations of the eNS [1]. The excellent gray fwhite-matter differentiation and multi planar imaging capabilities of MR allow a systematic analysis of the condition of the brain in infants and children. This is of interest for estimating prognosis and for genetic counseling. A classification is needed to serve as a guide to the great diversity of morphologic abnormalities and to make the acquired data useful. Such a system facilitates encoding, storage, and computer processing of data. We present a practical classification of congenital cerebral , cerebellar, and spinal malformations. Our classification is based on the morphologic abnormalities shown by MR and on the time at which the derangement of neural development occurred. A classification based on etiology is not as valuable because the various presumed causes rarely lead to a specific pattern of malformations. The abnor malities reflect the time the noxious agent interfered with neural development, rather than the nature of the noxious agent. The vulnerability of the various structures to adverse agents is greatest during the period of most active growth and development. -

Lissencephaly

LE JOURNAL CANADIEN DES SCIENCES NEUROLOGIQUES Lissencephaly MARGARET G. NORMAN, MAUREEN ROBERTS, J. SIROIS, L. J. M. TREMBLAY SUMMARY: The first reported case of tic heterogeneity. Lissencephaly and INTRODUCTION lissencephaly resulting from a consan- pachygyria may eventually be shown to Lissencephaly (agyria) is charac guinous union strengthens the supposi be due to different causes, some inher terized by a smooth brain, without tion that in some cases, it is transmitted ited, some acquired. The classical ex sulci or gyri. The microscopic as an autosomal recessive trait. Com amples of lissencephaly are different parison of this case with a sporadically morphologically from a case in which an anatomy of the cortex varies, some occuring case of lissencephaly, with dif tenatal cytomegalovirus infection had cases showing no laminae, others ferent cortical morphology, suggests produced a small smooth brain. This four laminae. Associated abnormal - that lissencephaly may be an example of suggests that antenatal viral infections ities are masses of heterotopic grey either varying gene expressivity or gene- are destructive rather than teratogenic. matter around the ventricles. Heterotopias of the inferior olivary nuclei and cerebellar roof nuclei are RESUME: Le premier cas de ment, il sera peut-etre demontre que la frequently present. Pachygyria is a lissencephalie resultant d'une union lissencephalie et la pachygyrie sont dues morphologically similar anomaly in consanguine renforcit I'hypothese qu'au a des causes differentes, certaines etant which the brain has wide simple moins dans certain cas la lissencephalie hereditaires, d'autres etant acquises. est transmise par un trait autosomal Les examples classiques de gyri. Some have regarded lissence recessif. -

Supratentorial Brain Malformations

Supratentorial Brain Malformations Edward Yang, MD PhD Department of Radiology Boston Children’s Hospital 1 May 2015/ SPR 2015 Disclosures: Consultant, Corticometrics LLC Objectives 1) Review major steps in the morphogenesis of the supratentorial brain. 2) Categorize patterns of malformation that result from failure in these steps. 3) Discuss particular imaging features that assist in recognition of these malformations. 4) Reference some of the genetic bases for these malformations to be discussed in greater detail later in the session. Overview I. Schematic overview of brain development II. Abnormalities of hemispheric cleavage III. Commissural (Callosal) abnormalities IV. Migrational abnormalities - Gray matter heterotopia - Pachygyria/Lissencephaly - Focal cortical dysplasia - Transpial migration - Polymicrogyria V. Global abnormalities in size (proliferation) VI. Fetal Life and Myelination Considerations I. Schematic Overview of Brain Development Embryology Top Mid-sagittal Top Mid-sagittal Closed Neural Tube (4 weeks) Corpus Callosum Callosum Formation Genu ! Splenium Cerebral Hemisphere (11-20 weeks) Hemispheric Cleavage (4-6 weeks) Neuronal Migration Ventricular/Subventricular Zones Ventricle ! Cortex (8-24 weeks) Neuronal Precursor Generation (Proliferation) (6-16 weeks) Embryology From ten Donkelaar Clinical Neuroembryology 2010 4mo 6mo 8mo term II. Abnormalities of Hemispheric Cleavage Holoprosencephaly (HPE) Top Mid-sagittal Imaging features: Incomplete hemispheric separation + 1)1) No septum pellucidum in any HPEs Closed Neural -

Structural Genomic Variation in Childhood Epilepsies with Complex Phenotypes

European Journal of Human Genetics (2014) 22, 896–901 & 2014 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1018-4813/14 www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Structural genomic variation in childhood epilepsies with complex phenotypes Ingo Helbig*,1, Marielle EM Swinkels2,3, Emmelien Aten4, Almuth Caliebe5, Ruben van ‘t Slot2, Rainer Boor1, Sarah von Spiczak1, Hiltrud Muhle1, Johanna A Ja¨hn1, Ellen van Binsbergen2, Onno van Nieuwenhuizen6, Floor E Jansen6, Kees PJ Braun6, Gerrit-Jan de Haan3, Niels Tommerup7, Ulrich Stephani1, Helle Hjalgrim8,9, Martin Poot2, Dick Lindhout2,3, Eva H Brilstra2, Rikke S Møller7,8 and Bobby PC Koeleman2 A genetic contribution to a broad range of epilepsies has been postulated, and particularly copy number variations (CNVs) have emerged as significant genetic risk factors. However, the role of CNVs in patients with epilepsies with complex phenotypes is not known. Therefore, we investigated the role of CNVs in patients with unclassified epilepsies and complex phenotypes. A total of 222 patients from three European countries, including patients with structural lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), dysmorphic features, and multiple congenital anomalies, were clinically evaluated and screened for CNVs. MRI findings including acquired or developmental lesions and patient characteristics were subdivided and analyzed in subgroups. MRI data were available for 88.3% of patients, of whom 41.6% had abnormal MRI findings. Eighty-eight rare CNVs were discovered in 71 out of 222 patients (31.9%). Segregation of all identified variants could be assessed in 42 patients, 11 of which were de novo. The frequency of all structural variants and de novo variants was not statistically different between patients with or without MRI abnormalities or MRI subcategories. -

Spectrum of Clinical and Associated MR Imaging Findings in Children with Olfactory Anomalies

Published March 17, 2016 as 10.3174/ajnr.A4738 ORIGINAL RESEARCH PEDIATRICS Spectrum of Clinical and Associated MR Imaging Findings in Children with Olfactory Anomalies X T.N. Booth and X N.K. Rollins ABSTRACT BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: The olfactory apparatus, consisting of the bulb and tract, is readily identifiable on MR imaging. Anom- alous development of the olfactory apparatus may be the harbinger of anomalies of the secondary olfactory cortex and associated structures. We report a large single-site series of associated MR imaging findings in patients with olfactory anomalies. MATERIALS AND METHODS: A retrospective search of radiologic reports (2010 through 2014) was performed by using the keyword “olfactory”; MR imaging studies were reviewed for olfactory anomalies and intracranial and skull base malformations. Medical records were reviewed for clinical symptoms, neuroendocrine dysfunction, syndromic associations, and genetics. RESULTS: We identified 41 patients with olfactory anomalies (range, 0.03–18 years of age; M/F ratio, 19:22); olfactory anomalies were bilateral in 31 of 41 patients (76%) and absent olfactory bulbs and olfactory tracts were found in 56 of 82 (68%). Developmental delay was found in 24 (59%), and seizures, in 14 (34%). Pituitary dysfunction was present in 14 (34%), 8 had panhypopituitarism, and 2 had isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. CNS anomalies, seen in 95% of patients, included hippocampal dysplasia in 26, cortical malformations in 15, malformed corpus callosum in 10, and optic pathway hypoplasia in 12. Infratentorial anomalies were seen in 15 (37%) patients and included an abnormal brain stem in 9 and an abnormal cerebellum in 3. Four patients had an abnormal membranous labyrinth. -

WES Gene Package Disorders of Sex Development (DSD)

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene package Disorders of Sex Development (DSD), version 7, 18‐2‐2019 Technical information DNA was enriched using Agilent SureSelect Clinical Research Exome V2 capture and paired‐end sequenced on the Illumina platform (outsourced). The aim is to obtain 8.1 Giga base pairs per exome with a mapped fraction of 0.99. The average coverage of the exome is ~50x. Duplicate reads are excluded. Data are demultiplexed with bcl2fastq Conversion Software from Illumina. Reads are mapped to the genome using the BWA‐MEM algorithm (reference: http://bio‐bwa.sourceforge.net/). Variant detection is performed by the Genome Analysis Toolkit HaplotypeCaller (reference: http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). The detected variants are filtered and annotated with Cartagenia software and classified with Alamut Visual. It is not excluded that pathogenic mutations are being missed using this technology. At this moment, there is not enough information about the sensitivity of this technique with respect to the detection of deletions and duplications of more than 5 nucleotides and of somatic mosaic mutations (all types of sequence changes). HGNC approved Phenotype description including OMIM phenotype ID(s) OMIM median depth % covered % covered % covered gene symbol gene ID >10x >20x >30x AKR1C1 No OMIM phenotype 600449 90 100 100 96 AKR1C4 {46XY sex reversal 8, modifier of}, 614279 600451 59 100 98 91 AMH Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome, type I, 261550 600957 97 100 100 100 AMHR2 Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome, type II, 261550 600956 -

Neuropathology Review.Pdf

Neuropathology Review Richard A. Prayson, MD Humana Press Contents NEUROPATHOLOGY REVIEW 2 Contents Contents NEUROPATHOLOGY REVIEW By RICHARD A. PRAYSON, MD Department of Anatomic Pathology Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH HUMANA PRESS TOTOWA, NEW JERSEY 4 Contents © 2001 Humana Press Inc. 999 Riverview Drive, Suite 208 Totowa, New Jersey 07512 For additional copies, pricing for bulk purchases, and/or information about other Humana titles, contact Humana at the above address or at any of the following numbers: Tel.: 973-256-1699; Fax: 973-256-8341; E-mail:[email protected]; Website: http://humanapress.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise without written permission from the Publisher. Due diligence has been taken by the publishers, editors, and authors of this book to assure the accuracy of the information published and to describe generally accepted practices. The contributors herein have carefully checked to ensure that the drug selections and dosages set forth in this text are accurate and in accord with the standards accepted at the time of publication. Notwithstanding, as new research, changes in government regulations, and knowledge from clinical experience relating to drug therapy and drug reactions constantly occurs, the reader is advised to check the product information provided by the manufacturer of each drug for any change in dosages or for additional warnings and contraindications. This is of utmost importance when the recommended drug herein is a new or infrequently used drug. It is the responsibility of the treating physician to determine dosages and treatment strategies for individual patients. -

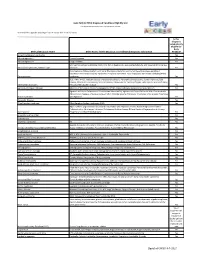

Early ACCESS Diagnosed Conditions List

Iowa Early ACCESS Diagnosed Conditions Eligibility List List adapted with permission from Early Intervention Colorado To search for a specific word type "Ctrl F" to use the "Find" function. Is this diagnosis automatically eligible for Early Medical Diagnosis Name Other Names for the Diagnosis and Additional Diagnosis Information ACCESS? 6q terminal deletion syndrome Yes Achondrogenesis I Parenti-Fraccaro Yes Achondrogenesis II Langer-Saldino Yes Schinzel Acrocallosal syndrome; ACLS; ACS; Hallux duplication, postaxial polydactyly, and absence of the corpus Acrocallosal syndrome, Schinzel Type callosum Yes Acrodysplasia; Arkless-Graham syndrome; Maroteaux-Malamut syndrome; Nasal hypoplasia-peripheral dysostosis-intellectual disability syndrome; Peripheral dysostosis-nasal hypoplasia-intellectual disability (PNM) Acrodysostosis syndrome Yes ALD; AMN; X-ALD; Addison disease and cerebral sclerosis; Adrenomyeloneuropathy; Siemerling-creutzfeldt disease; Bronze schilder disease; Schilder disease; Melanodermic Leukodystrophy; sudanophilic leukodystrophy; Adrenoleukodystrophy Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease Yes Agenesis of Corpus Callosum Absence of the corpus callosum; Hypogenesis of the corpus callosum; Dysplastic corpus callosum Yes Agenesis of Corpus Callosum and Chorioretinal Abnormality; Agenesis of Corpus Callosum With Chorioretinitis Abnormality; Agenesis of Corpus Callosum With Infantile Spasms And Ocular Anomalies; Chorioretinal Anomalies Aicardi syndrome with Agenesis Yes Alexander Disease Yes Allan Herndon syndrome Allan-Herndon-Dudley