Journal of Fungi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Candida Krusei: Biology, Epidemiology, Pathogenicity and Clinical Manifestations of an Emerging Pathogen

J. Med. Microbiol. - Vol. 41 (1994), 295-310 0 1994 The Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland REVIEW ARTICLE: CLINICAL MYCOLOGY Candida krusei: biology, epidemiology, pathogenicity and clinical manifestations of an emerging pathogen YUTHIKA H. SAMARANAYAKE and L. P. SAMARANAYAKE” Department of Pathology (Oral), Faculty of Medicine and Ord diology Unit, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Hong Kong, 34 Hospital Road, Hong Kong Summary. Early reports of Candida krusei in man describe the organism as a transient, infrequent isolate of minor clinical significance inhabiting the mucosal surfaces. More recently it has emerged as a notable pathogen with a spectrum of clinical manifestations such as fungaemia, endophthalmitis, arthritis and endocarditis, most of which usually occur in compromised patient groups in a nosocomial setting. The advent of human immunodeficiency virus infection and the widespread use of the newer triazole fluconazole to suppress fungal infections in these patients have contributed to a significant increase in C. krusei infection, particularly because of the high incidence of resistance of the yeast to this drug. Experimental studies have generally shown C. krusei to be less virulent than C. albicans in terms of its adherence to both epithelial and prosthetic surfaces, proteolytic potential and production of phospholipases. Furthermore, it would seem that C. krusei is significantlydifferent from other medically important Candida spp. in its structural and metabolic features, and exhibits different behaviour patterns towards host defences, adding credence to the belief that it should be re-assigned taxonomically. An increased awareness of the pathogenic potential of this yeast coupled with the newer molecular biological approaches to its study may facilitate the continued exploration of the epidemiology and pathogenesis of C. -

Downloaded (Additional File 1, Table S4)

Phylogenomics supports microsporidia as the earliest diverging clade of sequenced fungi Capella-Gutiérrez et al. Capella-Gutiérrez et al. BMC Biology 2012, 10:47 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7007/10/47 (31 May 2012) Capella-Gutiérrez et al. BMC Biology 2012, 10:47 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7007/10/47 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Phylogenomics supports microsporidia as the earliest diverging clade of sequenced fungi Salvador Capella-Gutiérrez, Marina Marcet-Houben and Toni Gabaldón* Abstract Background: Microsporidia is one of the taxa that have experienced the most dramatic taxonomic reclassifications. Once thought to be among the earliest diverging eukaryotes, the fungal nature of this group of intracellular pathogens is now widely accepted. However, the specific position of microsporidia within the fungal tree of life is still debated. Due to the presence of accelerated evolutionary rates, phylogenetic analyses involving microsporidia are prone to methodological artifacts, such as long-branch attraction, especially when taxon sampling is limited. Results: Here we exploit the recent availability of six complete microsporidian genomes to re-assess the long- standing question of their phylogenetic position. We show that microsporidians have a similar low level of conservation of gene neighborhood with other groups of fungi when controlling for the confounding effects of recent segmental duplications. A combined analysis of thousands of gene trees supports a topology in which microsporidia is a sister group to all other sequenced fungi. Moreover, this topology received increased support when less informative trees were discarded. This position of microsporidia was also strongly supported based on the combined analysis of 53 concatenated genes, and was robust to filters controlling for rate heterogeneity, compositional bias, long branch attraction and heterotachy. -

Candida Auris

microorganisms Review Candida auris: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Pathogenesis, Antifungal Susceptibility, and Infection Control Measures to Combat the Spread of Infections in Healthcare Facilities Suhail Ahmad * and Wadha Alfouzan Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait University, P.O. Box 24923, Safat 13110, Kuwait; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +965-2463-6503 Abstract: Candida auris, a recently recognized, often multidrug-resistant yeast, has become a sig- nificant fungal pathogen due to its ability to cause invasive infections and outbreaks in healthcare facilities which have been difficult to control and treat. The extraordinary abilities of C. auris to easily contaminate the environment around colonized patients and persist for long periods have recently re- sulted in major outbreaks in many countries. C. auris resists elimination by robust cleaning and other decontamination procedures, likely due to the formation of ‘dry’ biofilms. Susceptible hospitalized patients, particularly those with multiple comorbidities in intensive care settings, acquire C. auris rather easily from close contact with C. auris-infected patients, their environment, or the equipment used on colonized patients, often with fatal consequences. This review highlights the lessons learned from recent studies on the epidemiology, diagnosis, pathogenesis, susceptibility, and molecular basis of resistance to antifungal drugs and infection control measures to combat the spread of C. auris Citation: Ahmad, S.; Alfouzan, W. Candida auris: Epidemiology, infections in healthcare facilities. Particular emphasis is given to interventions aiming to prevent new Diagnosis, Pathogenesis, Antifungal infections in healthcare facilities, including the screening of susceptible patients for colonization; the Susceptibility, and Infection Control cleaning and decontamination of the environment, equipment, and colonized patients; and successful Measures to Combat the Spread of approaches to identify and treat infected patients, particularly during outbreaks. -

Filling Gaps in the Microsporidian Tree: Rdna Phylogeny of Chytridiopsis Typographi (Microsporidia: Chytridiopsida)

Parasitology Research (2019) 118:169–180 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-018-6130-1 GENETICS, EVOLUTION, AND PHYLOGENY - ORIGINAL PAPER Filling gaps in the microsporidian tree: rDNA phylogeny of Chytridiopsis typographi (Microsporidia: Chytridiopsida) Daniele Corsaro1 & Claudia Wylezich2 & Danielle Venditti1 & Rolf Michel3 & Julia Walochnik4 & Rudolf Wegensteiner5 Received: 7 August 2018 /Accepted: 23 October 2018 /Published online: 12 November 2018 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Microsporidia are intracellular eukaryotic parasites of animals, characterized by unusual morphological and genetic features. They can be divided in three main groups, the classical microsporidians presenting all the features of the phylum and two putative primitive groups, the chytridiopsids and metchnikovellids. Microsporidia originated from microsporidia-like organisms belong- ing to a lineage of chytrid-like endoparasites basal or sister to the Fungi. Genetic and genomic data are available for all members, except chytridiopsids. Herein, we filled this gap by obtaining the rDNA sequence (SSU-ITS-partial LSU) of Chytridiopsis typographi (Chytridiopsida), a parasite of bark beetles. Our rDNA molecular phylogenies indicate that Chytridiopsis branches earlier than metchnikovellids, commonly thought ancestral, forming the more basal lineage of the Microsporidia. Furthermore, our structural analyses showed that only classical microsporidians present 16S-like SSU rRNA and 5.8S/LSU rRNA gene fusion, whereas the standard eukaryote rRNA gene structure, although slightly reduced, is still preserved in the primitive microsporidians, including 18S-like SSU rRNA with conserved core helices, and ITS2-like separating 5.8S from LSU. Overall, our results are consistent with the scenario of an evolution from microsporidia-like rozellids to microsporidians, however suggesting for metchnikovellids a derived position, probably related to marine transition and adaptation to hyperparasitism. -

1. Economic, Ecological and Cultural Importance of Fungi

1. Economic, ecological and cultural importance of Fungi Fungi as food Yeast fermentations, Saccaromyces cerevesiae [Ascomycota] alcoholic beverages, yeast leavened bread Glucose 2 glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate + 2 ATP 2 NAD O2 2 NADH2 2 pyruvate + 2 ATP + 2 H2O 2 ethanol 2 acetaldehyde + 2 ATP + 2 CO2 Fungi as food Citric acid Aspergillus niger Fungi as food Cheese Penicillium camembertii, Penicillium roquefortii Rennet, chymosin produced by Rhizomucor miehei and recombinant Aspergillus niger, Saccharomyces cerevesiae chymosin first GM enzyme approved for use in food Fungi as food Quorn mycoprotein, produced from biomass of Fusarium venenatum [Ascomycota] Fungi as food Red yeast rice, Monascus purpureus Soy fermentations, Aspergillus oryzae [Ascomycota] contains lovastatin? Tempeh, made with Rhizopus oligosporus [Zygomycota] Fungi as food Other fungal food products: vitamins and enzymes • vitamins: riboflavin (vitamin B2), commercially produced by Ashbya gossypii • chocolate: cacao beans fermented before being made into chocolate with a mixture of yeasts and filamentous fungi: Candida krusei, Geotrichum candidum, Hansenula anomala, Pichia fermentans • candy: invertase, commercially produced by Aspergillus niger, various yeasts, enzyme splits disaccharide sucrose into glucose and fructose, used to make candy with soft centers • glucoamylase: Aspergillus niger, used in baking to increase fermentable sugar, also a cause of “baker’s asthma” • pectinases, proteases, glucanases for clarifying juices, beverages Fungi as food Perigord truffle, Tuber -

Alternatives in Molecular Diagnostics of Encephalitozoon and Enterocytozoon Infections

Journal of Fungi Review Alternatives in Molecular Diagnostics of Encephalitozoon and Enterocytozoon Infections Alexandra Valenˇcáková * and Monika Suˇcik Department of Biology and Genetics, University of Veterinary Medicine and Pharmacy, Komenského 73, 04181 Košice, Slovakia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 June 2020; Accepted: 20 July 2020; Published: 22 July 2020 Abstract: Microsporidia are obligate intracellular pathogens that are currently considered to be most directly aligned with fungi. These fungal-related microbes cause infections in every major group of animals, both vertebrate and invertebrate, and more recently, because of AIDS, they have been identified as significant opportunistic parasites in man. The Microsporidia are ubiquitous parasites in the animal kingdom but, until recently, they have maintained relative anonymity because of the specialized nature of pathology researchers. Diagnosis of microsporidia infection from stool examination is possible and has replaced biopsy as the initial diagnostic procedure in many laboratories. These staining techniques can be difficult, however, due to the small size of the spores. The specific identification of microsporidian species has classically depended on ultrastructural examination. With the cloning of the rRNA genes from the human pathogenic microsporidia it has been possible to apply polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques for the diagnosis of microsporidial infection at the species and genotype level. The absence of genetic techniques for manipulating microsporidia and their complicated diagnosis hampered research. This study should provide basic insights into the development of diagnostics and the pitfalls of molecular identification of these ubiquitous intracellular pathogens that can be integrated into studies aimed at treating or controlling microsporidiosis. Keywords: Encephalitozoon spp.; Enterocytozoonbieneusi; diagnosis; molecular diagnosis; primers 1. -

Managing Athlete's Foot

South African Family Practice 2018; 60(5):37-41 S Afr Fam Pract Open Access article distributed under the terms of the ISSN 2078-6190 EISSN 2078-6204 Creative Commons License [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0] © 2018 The Author(s) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 REVIEW Managing athlete’s foot Nkatoko Freddy Makola,1 Nicholus Malesela Magongwa,1 Boikgantsho Matsaung,1 Gustav Schellack,2 Natalie Schellack3 1 Academic interns, School of Pharmacy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University 2 Clinical research professional, pharmaceutical industry 3 Professor, School of Pharmacy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University *Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract This article is aimed at providing a succinct overview of the condition tinea pedis, commonly referred to as athlete’s foot. Tinea pedis is a very common fungal infection that affects a significantly large number of people globally. The presentation of tinea pedis can vary based on the different clinical forms of the condition. The symptoms of tinea pedis may range from asymptomatic, to mild- to-severe forms of pain, itchiness, difficulty walking and other debilitating symptoms. There is a range of precautionary measures available to prevent infection, and both oral and topical drugs can be used for treating tinea pedis. This article briefly highlights what athlete’s foot is, the different causes and how they present, the prevalence of the condition, the variety of diagnostic methods available, and the pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of the -

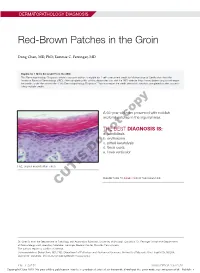

Red-Brown Patches in the Groin

DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS Red-Brown Patches in the Groin Dong Chen, MD, PhD; Tammie C. Ferringer, MD Eligible for 1 MOC SA Credit From the ABD This Dermatopathology Diagnosis article in our print edition is eligible for 1 self-assessment credit for Maintenance of Certification from the American Board of Dermatology (ABD). After completing this activity, diplomates can visit the ABD website (http://www.abderm.org) to self-report the credits under the activity title “Cutis Dermatopathology Diagnosis.” You may report the credit after each activity is completed or after accumu- lating multiple credits. A 66-year-old man presented with reddish arciform patchescopy in the inguinal area. THE BEST DIAGNOSIS IS: a. candidiasis b. noterythrasma c. pitted keratolysis d. tinea cruris Doe. tinea versicolor H&E, original magnification ×600. PLEASE TURN TO PAGE 419 FOR THE DIAGNOSIS CUTIS Dr. Chen is from the Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia. Dr. Ferringer is from the Departments of Dermatology and Laboratory Medicine, Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, Pennsylvania. The authors report no conflict of interest. Correspondence: Dong Chen, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, One Hospital Dr, MA204, DC018.00, Columbia, MO 65212 ([email protected]). 416 I CUTIS® WWW.MDEDGE.COM/CUTIS Copyright Cutis 2018. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted without the prior written permission of the Publisher. DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS DISCUSSION THE DIAGNOSIS: Erythrasma rythrasma usually involves intertriginous areas surface (Figure 1) compared to dermatophyte hyphae that (eg, axillae, groin, inframammary area). Patients tend to be parallel to the surface.2 E present with well-demarcated, minimally scaly, red- Pitted keratolysis is a superficial bacterial infection brown patches. -

The Phylogeny of Plant and Animal Pathogens in the Ascomycota

Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology (2001) 59, 165±187 doi:10.1006/pmpp.2001.0355, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on MINI-REVIEW The phylogeny of plant and animal pathogens in the Ascomycota MARY L. BERBEE* Department of Botany, University of British Columbia, 6270 University Blvd, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada (Accepted for publication August 2001) What makes a fungus pathogenic? In this review, phylogenetic inference is used to speculate on the evolution of plant and animal pathogens in the fungal Phylum Ascomycota. A phylogeny is presented using 297 18S ribosomal DNA sequences from GenBank and it is shown that most known plant pathogens are concentrated in four classes in the Ascomycota. Animal pathogens are also concentrated, but in two ascomycete classes that contain few, if any, plant pathogens. Rather than appearing as a constant character of a class, the ability to cause disease in plants and animals was gained and lost repeatedly. The genes that code for some traits involved in pathogenicity or virulence have been cloned and characterized, and so the evolutionary relationships of a few of the genes for enzymes and toxins known to play roles in diseases were explored. In general, these genes are too narrowly distributed and too recent in origin to explain the broad patterns of origin of pathogens. Co-evolution could potentially be part of an explanation for phylogenetic patterns of pathogenesis. Robust phylogenies not only of the fungi, but also of host plants and animals are becoming available, allowing for critical analysis of the nature of co-evolutionary warfare. Host animals, particularly human hosts have had little obvious eect on fungal evolution and most cases of fungal disease in humans appear to represent an evolutionary dead end for the fungus. -

Tinea Capitis 2014 L.C

BJD GUIDELINES British Journal of Dermatology British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of tinea capitis 2014 L.C. Fuller,1 R.C. Barton,2 M.F. Mohd Mustapa,3 L.E. Proudfoot,4 S.P. Punjabi5 and E.M. Higgins6 1Department of Dermatology, Chelsea & Westminster Hospital, Fulham Road, London SW10 9NH, U.K. 2Department of Microbiology, Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds LS1 3EX, U.K. 3British Association of Dermatologists, Willan House, 4 Fitzroy Square, London W1T 5HQ, U.K. 4St John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, St Thomas’ Hospital, Westminster Bridge Road, London SE1 7EH, U.K. 5Department of Dermatology, Hammersmith Hospital, 150 Du Cane Road, London W12 0HS, U.K. 6Department of Dermatology, King’s College Hospital, Denmark Hill, London SE5 9RS, U.K. 1.0 Purpose and scope Correspondence Claire Fuller. The overall objective of this guideline is to provide up-to- E-mail: [email protected] date, evidence-based recommendations for the management of tinea capitis. This document aims to update and expand Accepted for publication on the previous guidelines by (i) offering an appraisal of 8 June 2014 all relevant literature since January 1999, focusing on any key developments; (ii) addressing important, practical clini- Funding sources cal questions relating to the primary guideline objective, i.e. None. accurate diagnosis and identification of cases; suitable treat- ment to minimize duration of disease, discomfort and scar- Conflicts of interest ring; and limiting spread among other members of the L.C.F. has received sponsorship to attend conferences from Almirall, Janssen and LEO Pharma (nonspecific); has acted as a consultant for Alliance Pharma (nonspe- community; (iii) providing guideline recommendations and, cific); and has legal representation for L’Oreal U.K. -

Candida Krusei

P.O. Box 131375, Bryanston, 2074 Ground Floor, Block 5 Bryanston Gate, Main Road Bryanston, Johannesburg, South Africa www.thistle.co.za Tel: +27 (011) 463 3260 Fax: +27 (011) 463 3036 e-mail : [email protected] Please read this bit first The HPCSA and the Med Tech Society have confirmed that this clinical case study, plus your routine review of your EQA reports from Thistle QA, should be documented as a “Journal Club” activity. This means that you must record those attending for CEU purposes. Thistle will not issue a certificate to cover these activities, nor send out “correct” answers to the CEU questions at the end of this case study. The Thistle QA CEU No is: MT00025. Each attendee should claim THREE CEU points for completing this Quality Control Journal Club exercise, and retain a copy of the relevant Thistle QA Participation Certificate as proof of registration on a Thistle QA EQA. Cycle 22 Organism 6: Candida non-albicans species - Candida krusei Candida species are ubiquitous yeasts, found on many plants and as members of the normal flora of the alimentary tract of mammals and mucocutaneous membrane of humans. All areas of the human gastrointestinal tract can harbor Candid. The most commonly isolated species (50% to 70% of yeast isolates) from human gastrointestinal tract is Candida albicans, followed by Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida glabrata. C. glabrata is regarded as a symbiont of humans and can be isolated routinely from the oral cavity and from the gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary, and respiratory tracts of most individuals. As an agent of serious infection it has been associated with endocarditis, meningitis, and multifocal disseminated disease. -

Microsporidiosis in Vertebrate Companion Exotic Animals

Review Microsporidiosis in Vertebrate Companion Exotic Animals Claire Vergneau-Grosset 1,*,† and Sylvain Larrat 2,† Received: 13 October 2015; Accepted: 18 December 2015; Published: 24 December 2015 Academic Editor: Zhi-Yuan Chen 1 Zoological medicine service, Faculté de médecine vétérinaire, Université de Montréal, 3200 Sicotte, Saint-Hyacinthe, QC J2S2M2, Canada 2 Clinique Vétérinaire Benjamin Franklin, 38 rue du Danemark, ZA Porte Océane, 56400 Brech, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-450-773-8521 (ext. 16079) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Veterinarians caring for companion animals may encounter microsporidia in various host species, and diagnosis and treatment of these fungal organisms can be particularly challenging. Fourteen microsporidial species have been reported to infect humans and some of them are zoonotic; however, to date, direct zoonotic transmission is difficult to document versus transit through the digestive tract. In this context, summarizing information available about microsporidiosis of companion exotic animals is relevant due to the proximity of these animals to their owners. Diagnostic modalities and therapeutic challenges are reviewed by taxa. Further studies are needed to better assess risks associated with animal microsporidia for immunosuppressed owners and to improve detection and treatment of infected companion animals. Keywords: microsporidia; Encephalitozoon; Pleistophora; albendazole; fenbendazole 1. Introduction Microsporidia are eukaryotic organisms with the smallest known genome [1]. Microsporidia had been classified as amitochondriate due to their lack of visible mitochondria, but sequences homologous to genes coding for mitochondria have since been discovered in their genome and remnants of mitochondria have been visualized in their cytoplasm [2]; therefore, they have been reclassified as fungi based on phylogenic analysis of multiple proteins in their genome, clustering preferentially with fungal proteins [2,3].