Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jesucristo Médico Divino

JESUCRISTO MÉDICO DIVINO UNA CARTA PASTORAL SOBRE EL SACRAMENTO DE LA RECONCILIACIÓN ARZOBISPO ROBERT J. CARLSON JESUCRISTO MÉDICO DIVINO UNA CARTA PASTORAL SOBRE EL SACRAMENTO DE LA RECONCILIACIÓN ARZOBISPO ROBERT J. CARLSON ReverendÍsimo Robert J. Carlson Arzobispo de St. Louis Queridos Hermanos y Hermanas, Para comenzar esta carta pastoral sobre la Penitencia, me gustaría decir algunas palabras como introducción. Uno de los propósitos más importantes de esta carta es alejarnos de nuestra noción sobre la percepción centrada en la culpa del pecado y el sacramento: pecado significa sentimiento de culpa, o que Dios está enfadado, y que el Sacramento de la Penitencia es para aplacar esa culpa y la ira de Dios. Quiero que cambiemos a una noción diferente entorno al pecado: que el pecado significa que algo está profundamente herido en nosotros, que hemos debilitado o roto nuestra relación con Dios, y que el Sacramento de la Penitencia es donde el deseo de Dios por sanarnos se encuentra con nuestro deseo de ser curados. La primera sección de esta carta que habla sobre el pecado está diseñada principalmente para ayudarnos a aumentar nuestro conocimiento sobre cómo el pecado funciona en nuestras vidas. Al acercarnos al Sacramento de la Penitencia, pienso que mucha gente no hace la distinción crucial entre las acciones pecaminosas y las actitudes básicas del corazón como la raíz de todas esas acciones pecadoras. Dado que no hacemos esta distinción, no celebramos el sacramento lo más fructíferamente posible. Confesamos las mismas acciones pecaminosas una y otra vez y no hacemos mucho progreso en nuestras vidas. Concluimos que el sacramento no está haciendo nada por nosotros y, por frustración, dejamos de confesarnos. -

Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos Nº 337-338, Julio-Agosto 1978

CUADERNOS HISPANOAMERICANOS MADRID JULIO-AGOSTO 1978 337-338 CUADERNOS HISPANO AMERICANOS DIRECTOR JOSÉ ANTONIO MARAVALL JEFE DE REDACCIÓN FÉLIX GRANDE HAN DIRIGIDO CON ANTERIORIDAD ESTA REVISTA PEDRO LAIN ENTRALGO LUIS ROSALES DIRECCIÓN, SECRETARIA LITERARIA Y ADMINISTRACIÓN Centro Iberoamericano de Cooperación Avenida de los Reyes Católicos Teléfono 244 06 00 MADRID CUADERNOS HISPANOAMERICANOS Revista mensual de Cultura Hispánica Depósito legal: M 3875/1958 DIRECTOR JOSÉ ANTONIO MARAVALL JEFE DE REDACCIÓN FÉLIX GRANDE 337-338 DIRECCIÓN, ADMINISTRACIÓN Y SECRETARIA Centro Iberoamericano de Cooperación Avda. de los Reyes Católicos Teléfono 244 06 00 MADRID INDICE NUMEROS 337-338 (JULIO-AGOSTO 1978) HOMENAJE A CAMILO JOSE CELA Páginas JOSE GARCIA NIETO: Carta mediterránea a Camilo José Cela ... 5 FERNANDO QUIÑONES: Lo de Casasana 13 HORACIO SALAS: San Camilo 1936-Madrid. San Rómulo 1976-Bue- nos Aires 17 PEDRO LAIN ENTRALGO: Carta de un pedantón a un vagabundo por tierras de España 20 JOSE MARIA MARTINEZ CACHERO: El septenio 1940-1946 en la bi bliografia de Camilo José Cela : 34 ROBERT KIRSNER: Camilo José Cela: la conciencia literaria de su sociedad • 51 PAUL ILIE: La lectura del «vagabundaje» de Cela en la época pos franquista 61 EDMOND VANDERCAMMEN: Cinco ejemplos del ímpetu narrativo de Camilo José Cela 81 JUAN MARIA MARIN MARTINEZ: Sentido último de «La familia de Píí ^C'tirii DtJ3tt&¡> Qn JESUS SANCHEZ LOBATO: La adjetivación "en «La familia de Pas cual Duarte» 99 GONZALO SOBEJANO: «La Colmena»: olor a miseria 113 VICENTE CABRERA: En busca de tres personajes perdidos en «La Colmena» 127 D. W. McPHEETERS: Tremendismo y casticismo 137 CARMEN CONDE: Camilo José Cela: «Viaje a la Alcarria» 147 CHARLES V. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Brad a Mante

B radA mante Revista de Letras, 1 (2020) Hablo de aquella célebre doncella la cual abatió en duelo a Sacripante. Hija del duque Amón y de Beatriz, era muy digna hermana de Rinaldo. Con su audacia y valor asombra a Carlos y Francia entera aplaude su coraje, que en más de una ocasión quedó probado, en todo comparable al de su hermano. Orlando furioso II, 31 B radA mante Revista de Letras, 1 (2020) | issn 2695-9151 BradAmante. Revista de Letras Dirección Basilio Rodríguez Cañada - Grupo Editorial Sial Pigmalión José Ramón Trujillo - Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Comité científico internacional M.ª José Alonso Veloso - Universidade de Santiago de Compostela Carlos Alvar - Université de Genève (Suiza) José Luis Bernal Salgado - Universidad de Extremadura Justo Bolekia Boleká - Universidad de Salamanca Rafael Bonilla Cerezo - Universidad de Córdoba Randi Lise Davenport - Universidad de Tromsø (Noruega) J. Ignacio Díez - Universidad Complutense de Madrid Ángel Gómez Moreno - Universidad Complutense de Madrid Fernando González García - Universidad de Salamanca Francisco Gutiérrez Carbajo - Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia Javier Huerta Calvo - Universidad Complutense de Madrid José Manuel Lucía Megías - Universidad Complutense de Madrid Karla Xiomara Luna Mariscal - El Colegio de México (México) Ridha Mami - Université La Manouba (Túnez) Fabio Martínez - Universidad del Valle (Colombia) Carmiña Navia Velasco - Universidad del Valle (Colombia) José María Paz Gago - Universidade da Coruña José Antonio Pascual Rodríguez - Real Academia -

Jonesexcerpt.Pdf

2 The Texts—An Overview N’ot que trois gestes en France la garnie; ne cuit que ja nus de ce me desdie. Des rois de France est la plus seignorie, et l’autre aprés, bien est droiz que jeu die, fu de Doon a la barbe florie, cil de Maience qui molt ot baronnie. De ce lingnaje, ou tant ot de boidie, fu Ganelon, qui, par sa tricherie, en grant dolor mist France la garnie. La tierce geste, qui molt fist a prisier, fu de Garin de Monglenne au vis fier. Einz roi de France ne vodrent jor boisier; lor droit seignor se penerent d’aidier, . Crestïenté firent molt essaucier. [There were only threegestes in wealthy France; I don’t think any- one would ever contradict me on this. The most illustrious is the geste of the kings of France; and the next, it is right for me to say, was the geste of white-beardedPROOF Doon de Mayence. To this lineage, which was full of disloyalty, belonged Ganelon, who, by his duplic- ity, plunged France into great distress. The thirdgeste , remarkably worthy, was of the fierce Garin de Monglane. Those of his lineage never once sought to deceive the king of France; they strove to help their rightful lord, . and they advanced Christianity.] Bertrand de Bar-sur-Aube, Girart de Vienne Since the Middle Ages, the corpus of chansons de geste has been di- vided into groups based on various criteria. In the above prologue to the thirteenth-century Girart de Vienne, Bertrand de Bar-sur-Aube classifies An Introduction to the Chansons de Geste by Catherine M. -

Religión Y Política En El Leviatán La Teología Política De Thomas Hobbes

Universidad de Chile Facultad de Filosofía Escuela de Postgrado Departamento de Filosofía Religión y Política en el Leviatán La teología política de Thomas Hobbes. Un análisis crítico Tesis para optar al Grado Académico de Doctor en Filosofía con mención en Moral y Política Autor: Jorge A. Alfonso Vargas Profesor Patrocinante: Fernando Quintana Bravo Santiago, marzo 2011 Agradecimientos . 4 Dedicatoria . 5 I.-Introducción . 6 Metodología . 14 I.- LA IDEA DE RELIGIÓN (EW III, 1:12) . 16 1.- El Origen de la Religión: Las Causas Naturales y Psicológicas. 16 2.- Religión y Política . 21 3.- La Verdadera Religión . 26 II.- La República Cristiana II (EW III, 3, 32-41) . 36 1.- El Gobierno de Dios . 36 2.- El Reino de Dios . 39 3.- El Libro de Job como Clave Hermenéutica . 44 4.- Las Leyes de Dios: Deberes y Derechos, Honor y Deshonor . 47 5.- Los Atributos Divinos y la Posibilidad de una Teología . 52 III.- De la República Cristiana II (EW III, 3: 32) . 64 1.- Ciencia y Religión . 64 2.- La Política Cristiana y la Palabra de Dios . 69 3.- La Visión Materialista del Cristianismo . 79 4.- El Reino de Dios Nuevamente . 103 5.- La Iglesia . 105 6.- Los Profetas y el Pacto . 109 7.- El Reino de Dios según Hobbes . 119 8.- El Dominio Real de Cristo y el Poder Eclesiástico . 122 9.- El Poder Civil y la Obediencia Debida . 127 10.- El Poder Soberano . 136 11.- La Misión de los Reyes-Pastores . 142 12.- La Autoridad para Interpretar las Escrituras . 148 IV.-De lo Necesario para ser recibido en el Reino Celestial (E W III, 3,43) . -

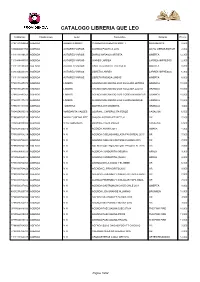

Catalogoqueleopedrodevaldivia40.Pdf

CATALOGO LIBRERIA QUE LEO CodBarras Clasificacion Autor Titulo Libro Editorial Precio 7798141020454 AGENDA ALBERTO MONTT CUADERNO ALBERTO MONTT MONOBLOCK 8,500 1000000001709 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS AGENDA POLITICA 2012 OCHO LIBROS EDITOR 2,900 1111111199121 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS DIARIO NARANJA ARTISTA OMERTA 12,300 1111444445551 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS IMANES LARREA LARREA IMPRESOS 2,900 1111111198988 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA GRANATE CALCULO OMERTA 8,200 3333344443330 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA LARREA LARREA IMPRESOS 6,900 1111111198995 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA ROSADA LINEAS OMERTA 8,500 7798071447376 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 ANILLADA LETRAS GRANICA 10,000 7798071447390 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 ANILLADA LLUVIA GRANICA 10,000 7798071447352 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 COSIDA BANDERAS GRANICA 10,000 7798071447338 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 COSIDA BOSQUE GRANICA 10,000 7798071444399 AGENDA . MAITENA MAITENA 007 MAGENTA GRANICA 1,000 7804654930019 AGENDA MARGARITA VALDES JOURNAL, CAPERUCITA FEROZ VASALISA 6,500 7798083702128 AGENDA MARIA EUGENIA PITE CHUICK AGENDA PERPETUA VR 7,200 7804654930002 AGENDA NICO GONZALES JOURNAL PIZZA PALIZA VASALISA 6,500 7804634920016 AGENDA N N AGENDA AMAKA 2011 AMAKA 4,900 7798083704214 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO ANILLADA PAVO REAL 2015 VR 7,000 7798083704221 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO CANTONE FLORES 2015 VR 7,000 7798083704238 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO CANTONE PAVO REAL 2015 VR 7,000 9789568069025 AGENDA N N AGENDA CONDORITO (NEGRA) ORIGO 9,900 9789568069032 AGENDA -

San Agustín Y Los Sentidos Espirituales: El Caso De La Visión Interior Fernando Martin-De Blassi

Teología y Vida, 59/1 (2018), 9-32 9 San Agustín y los sentidos espirituales: el caso de la visión interior Fernando Martin-De Blassi FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE CUYO [email protected] Resumen: Discurriendo en torno a la visión de Dios, Agustín de Hipona afi rma en la Epístola 147 que los ojos interiores son jueces de los exteriores (Cum ergo interiores oculi iudices sivi oculorum exteriorum, 17, 41), pues los interiores ven muchas cosas que los exteriores no ven y las percepciones corporales, por su parte, no se juzgan con ojos carnales sino con aquellos del corazón (oculis cordis). El tema particular de esta disquisición es planteado igualmente en las Ep. 92 y 148 y también en el libro XXII (cp. 29) de La ciudad de Dios. Sobre la base de este tratamiento, el presente trabajo estriba en dilucidar las notas signifi cativas que el Obispo de Hipona desarrolla a propósito de la visión interior y de su superioridad con respecto a la visión corpórea. Para la interpretación de los textos, se acude al apoyo instrumental de fuentes, junto con sus correspondientes versiones en lenguas modernas. Palabras clave: Agustín de Hipona, sentidos espirituales, visión externa, vi- sión interna. Abstract: In the context of a consideration on the God’s vision, Augustine of Hippo states in Epistle 147 that the inner eyes are judges of the exterior ones (Cum ergo interior oculi iudices sivi oculorum exteriorum, 17, 41), because the inner eyes see many things that the others do not see, and the corporal perceptions are not judged by carnal eyes. -

FAQ-Brochure SPANISH.Pdf

Escrito por Tom Cantor Presidente, Fundador y Director Ejecutivo Scantibodies Laboratory, Inc. Scantibodies Clinical Laboratory, Inc. Scantibodies Biologics, Inc. Israel Restoration Ministries Light & Life Foundation Creation & Earth History Museum Friendship with God Radio Ministry Preguntas Frecuentes 1. ¿Respaldan las Escrituras Hebreas la tri-unidad de Dios? 2. ¿Es el Mesías judío Dios como hombre? 3. ¿Es el Señor Jesucristo Dios? 4. ¿Es posible que un hombre pueda ver a Dios el Hijo? 5. ¿Cómo puede ser identificado el Mesías judío? 6. ¿Las Escrituras Hebreas sostienen el nacimiento virginal? 7. ¿Tienen todos los hombres una naturaleza pecaminosa? 8. ¿Hay un mediador entre Dios y los hombres? 9. ¿Cuál es la diferencia entre un gentil y un cristiano? 10. ¿Cuál es la diferencia entre Israel y la Iglesia? 11. ¿Quién es un judío? 12. ¿Es posible ser judío y cristiano a la misma vez? 13. ¿Por qué los rabinos no enseñan al pueblo judío sobre Jesús el Mesías? 14. ¿Por qué algunos judíos dudan de la existencia de Dios? 15. ¿Las Escrituras Hebreas enseñan del cielo y el infierno? 16. ¿Cuál es el plan de Dios de salvación para el pueblo judío? 17. ¿Es el bautismo un ritual judío? 18. ¿Vale la pena para un judío recibir al Señor Jesucristo? 19. ¿Cuál es el propósito de Dios para el pueblo judío? 1 20. ¿Qué paz trajo el Mesías judío a la tierra? 21. ¿Van los judíos automáticamente al cielo? 22. ¿Dónde estaba Dios durante el desastre Nazi? 23. ¿Puede el hombre escribir y pronunciar el nombre de Dios? 24. ¿Se encuentra el nombre de Jesucristo en las Escrituras Hebreas? 25. -

Post-Chrétien Verse Romance the Manuscript Context

Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes Journal of medieval and humanistic studies 14 | 2007 L’héritage de Chrétien de Troyes Post-Chrétien Verse Romance The Manuscript Context Keith Busby Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/crm/2646 DOI: 10.4000/crm.2646 ISSN: 2273-0893 Publisher Classiques Garnier Printed version Date of publication: 15 December 2007 Number of pages: 11-24 ISSN: 2115-6360 Electronic reference Keith Busby, « Post-Chrétien Verse Romance », Cahiers de recherches médiévales [Online], 14 | 2007, Online since 15 December 2010, connection on 13 October 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/crm/2646 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/crm.2646 © Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes Post-Chrétien Verse Romance : The Manuscript Context1 The manuscripts in which the post-Chrétien (« epigonal ») verse romances are preserved can speak volumes about their transmission and reception. In some cases, these are intimately bound up with the works of the master, although the intertextuality of the whole corpus of verse romance transcends the codicological context. I shall review here selected manuscripts in which some epigonal romances have been transmitted and what they can tell us about ways in which these texts were read in the Middle Ages. The romances in question are : Renaut de Bâgé (Beaujeu), Le bel inconnu Paien de Maisières, La mule sans frein Le chevalier à l’épée Raoul de Houdenc, Meraugis de Portlesguez Raoul (de Houdenc ?), La vengeance Raguidel L’âtre périlleux Guillaume le Clerc, Fergus Hunbaut Yder Floriant et Florete Le chevalier aux deux épées Girard d’Amiens, Escanor Claris et Laris Jehan, Les merveilles de Rigomer Compared with Chrétien’s romances, themselves only preserved in half-a- dozen copies on average (but fifteen plus fragments of Perceval), these works are mainly codicological unica, with only Meraugis de Portlesguez, La vengeance Raguidel, L’âtre périlleux, and Fergus surviving in more than one complete exemplar. -

The Role of Images in Medieval Depictions of Muslims

Suzanne Akbari IMAGINING ISLAM: The Role of Images in Medieval Depictions of Muslims On the edges of medieval Europe, there was real contact between Chris tians and Muslims. Multicultural, multi-religious societies existed in al-Andalus and Sicily, while cultural contact of a more contentious sort took place in the Near East. In most parts of medieval Europe, how ever, Muslims were seen rarely or not at all, and Islam was known only at second - or third-hand. Western European accounts written during the Middle Ages invariably misrepresent Islam; they vary only to the degree with which they parody the religion and its adherents. One might imagine that such misrepresentation is simply due to the limited information available to the medieval European curious about Islam and the Prophet. If such were the case, one would expect to find a linear progression in medieval accounts of Islam, moving from extremely fanci ful depictions to more straightforward, factual chronicles. Instead, one finds accurate, even rather compassionate accounts of Islamic theology side by side with bizarre, antagonistic, and even hateful depictions of Muslims and their belief. During the twelfth century, the French abbot of Cluny, Peter the Venerable, engaged several translators and went to Muslim Spain to produce a translation of the Qur'an and to learn about Islam in order to effect the conversion of Muslims to Christianity by means of rational persuasion, approaching them, as Peter himself put it, "not in hatred, but in love."1 During the same century, however, the chanson de geste tradition flourished in France and began to be exported into the literatures of England and Germany.2 In these twelfth-century epics glorifying war and chivalric heroism, Muslims are depicted as basically similar to Christians: the structure of their armies, their kings, and their martial techniques are essentially the same. -

Job Y El Sentido Del Sufrimiento

Job y el sentido del sufrimiento Alejandro Ramos Universidad FASTA Ediciones Mar del Plata, Argentina. Febrero 2018 Néstor Alejandro Ramos JOB Y EL SENTIDO DEL SUFRIMIENTO Universidad FASTA Mar del Plata, 2018 Ramos, Néstor Alejandro Job y el sentido del sufrimiento / Néstor Alejandro Ramos. - 1a ed . - Mar del Plata : Universidad FASTA, 2018. Libro digital, PDF/A Archivo Digital: descarga ISBN 978-987-1312-83-2 1. Teología . 2. Biblia. 3. Espiritualidad. I. Título. CDD 230 Fecha de catalogación: 07/02/2018 con aprobación eclesiástica Mons. Gabriel Mestre, obispo de Mar del Plata, 12/12/2017 Imagen de Tapa Job on the Ddunghill By Gonzalo Carrasco (1859 - 1936) – painter (Mexican) Born in State of Mexico. Dead in Puebla.Details of artist on Google Art Project [Public domain or Public domain], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AGonzalo_Carrasco_- _Job_on_the_Dunghill_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg via Wikimedia Commons Diseño de tapa Matias Gabriel Bautista Editor Lic. José Miguel Ravasi © 2018 Universidad FASTA Ediciones © 2018 Alejandro Ramos Gascón 3145 – B7600FNK Mar del Plata, Argentina +54 223 4990400 [email protected] Miembro de la Red de Editoriales de Universidades Privadas de la República Argentina, REUP Job y el sentido del sufrimiento por Alejandro Ramos se distribuye bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional. CONTENIDO INTRODUCCIÓN ......................................................................... 4 El autor de la obra ...............................................................