Document:EPP Maroc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pattern of Reproductive Life in a Berber Population of Morocco

The Pattern of Reproductive Life in a Berber Population of Morocco aEmile Crognier, bCristina Bernis, aSilvia Elizondo, and bCarlos Varea aCentre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Equipe de Recherche 221 "Dynamique biocul- turelle," 13100 Aix-en-Provence, France; and bUnidad de Antropología, Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Ciéncias, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid 34, Spain ABSTRACT: Reproductive patterns were studied from data collected in 1,450 Berber households in the province of Marrakesh, Morocco in 1984. Women aged 45-49 years had a mean of 8.9 pregnancies to achieve 5.7 living children. Social influences on fertility rates show the importance of tradition, particularly through time-dependent variables such as age at marriage, waiting time to first birth, interbirth intervals, and duration of breastfeeding. Birth control does not appear to affect the tempo of fertility; rather, its main use is to bring the reproductive period to a close. The comparison of two subsamples of women separated by a 25-year interval indicates an actual acceleration of the tempo of fertility by the reduction of waiting time to first birth and of interbirth intervals. The supposed ongoing process of demographic transition is not clearly observed in this population. Nagi (1983), analyzing the numer- thousand, respectively), and Tunisia ous studies performed in Muslim coun- (46 and 28.2 per thousand). In spite of tries on fertility trends and their effects a drop of some 28 per cent in 23 years, upon demography and social struc- Moroccan fertility remains high. The tures, questioned whether there was mean data available for urban and any evidence of a demographic transi- rural areas in the province of Marra- tion in these societies, since fertility kesh still average 6.5 and 8.3 full-term rates remain high despite economic births per woman, respectively, at the development and a drop in mortality end of reproductive life (Crognier and rates. -

Transfers Excursions

TRANSFERS & EXCURSIONS We can, at any time of the day, provide you with a driver and a vehicle to take you wherever you want. Rates are shown below depending on the destination and number of people participating at the travel: Mini bus 1 to 7 Pers Marrakesh airport or Marrakech center 4,5€/pers Go Marrakesh historical center half day 10€/pers Go /Return Marrakesh historical center 1 day 20€/pers Go/Return Lake of Lalla Takerkoust 20€/pers Go/Return Ourika 25€/pers Go/Return Oukaimiden 25€ /pers Go/Return Essaouira 30€/pers Go/Return Asni Ouirgane 20€/pers Go/Return Imlil 20€/pers Go/Return Casacade Ouzoud 30€ /pers Go/Return Ait Ben Haddou 30€ pers Go/Return Quad bike Durée: 2.30 H 45€ / 2 pers / 1 quad 35 € / 1 pers / 1 quad Camel Ride 25€/pers All our excursions are with drivers, fuel and insurance included Excursion to Ourika Valleys (Berber villages and waterfalls) Duration: Full day Escape from Marrakech, for a full day excursion to the Ourika valley, a green oasis at the foot of the towering Atlas Mountains. This beautiful green valley is one of the best preserved of Morocco. Departure at 10 am just after breakfast towards the Atlas. • A free Bottle of water per participant • Smile and good mood and good service all day • Free time: Berber village market (market days: Monday and Friday). • Visit the small waterfalls of Seti Fatma with local mountain guide. • Lunch (not included, our driver can recommend you some restaurants But the final choice is yours) • Back in Marrakech in the late of the afternoon. -

Weathering Morocco's Syria Returnees | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 2148 Weathering Morocco's Syria Returnees by Vish Sakthivel Sep 25, 2013 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Vish Sakthivel Vish Sakthivel was a 2013-14 Next Generation Fellow at The Washington Institute. Brief Analysis The Moroccan government should be encouraged to adopt policies that preempt citizens from joining the Syrian jihad and deradicalize eventual returnees. ast week, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) released a video titled "Morocco: The Kingdom of Corruption L and Tyranny." In addition to pushing young Moroccans to join the jihad, the video inveighs against King Muhammad VI -- one of several public communiques in what appears to be an escalating campaign against the ruler. The timing of the video could not be more unsettling. A week before its release, against the backdrop of an increasingly insecure Sahel region, the government arrested several jihadist operatives in the northern cities of Fes, Meknes, and Taounate and the southern coastal town of Tiznit. Meanwhile, Moroccan fighters are traveling to Syria in greater numbers and forming their own jihadist groups, raising concerns about what they might do once they return home. VIDEO AND RESPONSE T he video released by al-Andalus, AQIM's media network, begins by outlining the king's alleged profiteering and corruption, citing WikiLeaks and the nonfiction book Le Roi Predateur by Catherine Graciet and Eric Laurent. It then moves to the king's close friends Mounir Majidi and Fouad Ali el-Himma, accusing them of perpetuating monopolies and patronage networks that impoverish the country while allowing the king to become one of world's richest monarchs. -

Deliverable 1

Lot No. 4 : Project Final Evaluation : « Financial services », Agency for Partnership for Progress – MCA ‐ Morocco Contract No. APP/2012/PP10/QCBS/ME‐16‐lot 4 Deliverable 1: Methodology Report Submitted by : North South Consultants Exchange JUNE 19TH 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1.CONTEXT ................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2.OVERVIEW OF THE FINANCIAL SERVICES PROJECT ..................................................................................... 2 1.3.PURPOSE OF THE FSP FINAL EVALUATION ............................................................................................. 4 2.METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. COMPREHENSIVE APPROACH .......................................................................................................... 5 2.2. STAKEHOLDERS .......................................................................................................................... 6 2.2.1. APP ................................................................................................................................................... 6 2.2.2. Supervisory Institution ..................................................................................................... -

Pauvrete, Developpement Humain

ROYAUME DU MAROC HAUT COMMISSARIAT AU PLAN PAUVRETE, DEVELOPPEMENT HUMAIN ET DEVELOPPEMENT SOCIAL AU MAROC Données cartographiques et statistiques Septembre 2004 Remerciements La présente cartographie de la pauvreté, du développement humain et du développement social est le résultat d’un travail d’équipe. Elle a été élaborée par un groupe de spécialistes du Haut Commissariat au Plan (Observatoire des conditions de vie de la population), formé de Mme Ikira D . (Statisticienne) et MM. Douidich M. (Statisticien-économiste), Ezzrari J. (Economiste), Nekrache H. (Statisticien- démographe) et Soudi K. (Statisticien-démographe). Qu’ils en soient vivement remerciés. Mes remerciements vont aussi à MM. Benkasmi M. et Teto A. d’avoir participé aux travaux préparatoires de cette étude, et à Mr Peter Lanjouw, fondateur de la cartographie de la pauvreté, d’avoir été en contact permanent avec l’ensemble de ces spécialistes. SOMMAIRE Ahmed LAHLIMI ALAMI Haut Commissaire au Plan 2 SOMMAIRE Page Partie I : PRESENTATION GENERALE I. Approche de la pauvreté, de la vulnérabilité et de l’inégalité 1.1. Concepts et mesures 1.2. Indicateurs de la pauvreté et de la vulnérabilité au Maroc II. Objectifs et consistance des indices communaux de développement humain et de développement social 2.1. Objectifs 2.2. Consistance et mesure de l’indice communal de développement humain 2.3. Consistance et mesure de l’indice communal de développement social III. Cartographie de la pauvreté, du développement humain et du développement social IV. Niveaux et évolution de la pauvreté, du développement humain et du développement social 4.1. Niveaux et évolution de la pauvreté 4.2. -

Moroccobrochure.Pdf

2 SPAIN MEDITERRANEAN SEA Saïdia Rabat ATLANTIC OCEAN Zagora ALGERIA CANARY ISLANDS MAURITANIA 3 Marrakech 5 Editorial 6 A thousand-year-old pearl charged with history 8 Not to be missed out on 10 A first look around the city and its surroundings 12 Arts and crafts - the city’s designer souks 16 Marrakech, The Fiery 18 A fairytale world 20 Marrakech in a new light 22 The hinterland: lakes, mountains and waterfalls 24 Just a step away 26 Information and useful addresses 4 5 Editorial The Pearl of the South The moment the traveller sets foot in Marrakech, he is awestruck by the contrast in colours – the ochre of its adobe city walls, and its bougainvillea- covered exteriors, from behind which great bouquets of palm trees and lush greenery burst forth. A magnificent array of architecture set against the snow-capped peaks of the High Atlas Mountains, beneath a brilliant blue sky that reveals the city’s true nature – a luxuriant, sun-soaked oasis, heady with the scent of the jasmine and orange blossom that adorn its gardens. Within its adobe walls, in the sun-streaked shade, the medina’s teeming streets are alive with activity. A hubbub of voices calling back and forth, vibrant colours, the air filled with the fragrance of cedar wood and countless spices. Sounds, colours and smells unite gloriously to compose an astonishing sensorial symphony. Marrakech, city of legend, cultural capital, inspirer of artists, fashions and Bab Agnaou leads to Marrakech’s events; Marrakech with its art galleries, festivals, and exhibitions; Marrakech main palaces with its famous names, its luxurious palaces and its glittering nightlife. -

MPLS VPN Service

MPLS VPN Service PCCW Global’s MPLS VPN Service provides reliable and secure access to your network from anywhere in the world. This technology-independent solution enables you to handle a multitude of tasks ranging from mission-critical Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP), Customer Relationship Management (CRM), quality videoconferencing and Voice-over-IP (VoIP) to convenient email and web-based applications while addressing traditional network problems relating to speed, scalability, Quality of Service (QoS) management and traffic engineering. MPLS VPN enables routers to tag and forward incoming packets based on their class of service specification and allows you to run voice communications, video, and IT applications separately via a single connection and create faster and smoother pathways by simplifying traffic flow. Independent of other VPNs, your network enjoys a level of security equivalent to that provided by frame relay and ATM. Network diagram Database Customer Portal 24/7 online customer portal CE Router Voice Voice Regional LAN Headquarters Headquarters Data LAN Data LAN Country A LAN Country B PE CE Customer Router Service Portal PE Router Router • Router report IPSec • Traffic report Backup • QoS report PCCW Global • Application report MPLS Core Network Internet IPSec MPLS Gateway Partner Network PE Router CE Remote Router Site Access PE Router Voice CE Voice LAN Router Branch Office CE Data Branch Router Office LAN Country D Data LAN Country C Key benefits to your business n A fully-scalable solution requiring minimal investment -

Print Itinerary

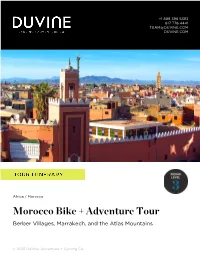

+1 888 396 5383 617 776 4441 [email protected] DUVINE.COM Africa / Morocco Morocco Bike + Adventure Tour Berber Villages, Marrakech, and the Atlas Mountains © 2021 DuVine Adventure + Cycling Co. Work your way through the streets of the medina in Marrakech with a local guide, absorbing the outpouring of sights, smells, and sounds Ride in the Kik Valley, on village roads shared with donkeys, and on routes lined with flowering almond and cherry trees Hike beside a river to the base of Toubkal, the highest peak in the Atlas Mountains Enjoy a delectable Berber-style lunch while biking between remote villages Discover the port village of Essaouira, with its historic architecture and fresh, fragrant cuisine Meet the makers of Moroccan argan oil and French-style wine Arrival Details Departure Details Airport City: Airport City: Marrakech, Morocco Marrakech, Morocco Pick-Up Location: Drop-Off Location: Marrakech Airport or hotel Marrakech Airport Pick-Up Time: Drop-Off Time: 10:00 am 11:00 am NOTE: DuVine provides group transfers to and from the tour, within reason and in accordance with the pick-up and drop-off recommendations. In the event your train, flight, or other travel falls outside the recommended departure or arrival time or location, you may be responsible for extra costs incurred in arranging a separate transfer. Emergency Assistance For urgent assistance on your way to tour or while on tour, please always contact your guides first. You may also contact the Boston office during business hours at +1 617 776 4441 or [email protected]. Tour By Day DAY 1 Morocco and the Ourika Valley Welcome to the Kingdom of Morocco, a country rich in history, culture, and beauty. -

Community Perception and Knowledge of Cystic Echinococcosis in the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco

Thys et al. BMC Public Health (2019) 19:118 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6372-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Community perception and knowledge of cystic echinococcosis in the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco Séverine Thys1,2* , Hamid Sahibi3, Sarah Gabriël4, Tarik Rahali5, Pierre Lefèvre6, Abdelkbir Rhalem3, Tanguy Marcotty7, Marleen Boelaert1 and Pierre Dorny8,2 Abstract Background: Cystic echinococcosis (CE), a neglected zoonosis caused by the larval stage of the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus, remains a public health issue in many developing countries that practice extensive sheep breeding. Control of CE is difficult and requires a community-based integrated approach. We assessed the communities’ knowledge and perception of CE, its animal hosts, and its control in a CE endemic area of the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco. Methods: We conducted twenty focus group discussions (FGDs) stratified by gender with villagers, butchers and students in ten Berber villages that were purposefully selected for their CE prevalence. Results: This community considers CE to be a severe and relatively common disease in humans and animals but has a poor understanding of the parasite’s life cycle. Risk behaviour and disabling factors for disease control are mainly related to cultural practices in sheep breeding and home slaughtering, dog keeping, and offal disposal at home, as well as in slaughterhouses. Participants in our focus group discussions were supportive of control measures as management of canine populations, waste disposal, and monitoring of slaughterhouses. Conclusions: The uncontrolled stray dog population and dogs having access to offal (both at village dumps and slaughterhouses) suggest that authorities should be more closely involved in CE control. -

Feasibility Study on Water Resources Development in Rural Area Inthe Kingdom of Morocco

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY THE GOVERNMENT OF THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO FEASIBILITY STUDY ON WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT IN RURAL AREA INTHE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO FINAL REPORT VOLUME V SUPPORTING REPORT (2.B) FEASIBILITY STUDY AUGUST, 2001 JOINT VENTURE OF NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. AND NIPPON GIKEN INC. LIST OF FINAL REPORT VOLUMES Volume I: Executive Summary Volume II: Main Report Volume III: Supporting Report (1) Basic Study Supporting Report I: Geology Supporting Report II: Hydrology and Flood Mitigation Supporting Report III: Socio-economy Supporting Report IV: Environmental Assessment Supporting Report V: Soils, Agriculture and Irrigation Supporting Report VI: Existing Water Resources Development Supporting Report VII: Development Scale of the Projects Supporting Report VIII: Project Evaluation and Prioritization Volume IV: Supporting Report (2.A) Feasibility Study Supporting Report IX: Aero-Photo and Ground Survey Supporting Report X: Geology and Construction Material Supporting Report XI: Hydro-meteorology and Hydro-geology Supporting Report XII: Socio-economy Supporting Report XIII: Soils, Agriculture and Irrigation Volume V: Supporting Report (2.B) Feasibility Study Supporting Report XIV: Water Supply and Electrification Supporting Report XV: Determination of the Project Scale and Ground Water Recharging Supporting Report XVI: Natural and Social Environment and Resettlement Plan Supporting Report XVII: Preliminary Design and Cost Estimates Supporting Report XVIII: Economic and Financial Evaluation Supporting Report XIX: Implementation Program Volume VI: Drawings for Feasibility Study Volume VII: Data Book Data Book AR: Aero-Photo and Ground Survey Data Book GC: Geology and Construction Materials Data Book HY: Hydrology Data Book SO: Soil Survey Data Book NE: Natural Environment Data Book SE: Social Environment Data Book EA: Economic Analysis The cost estimate is based on the price level and exchange rate of April 2000. -

Community Perception and Knowledge of Cystic Echinococcosis in the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco

Thys et al. BMC Public Health (2019) 19:118 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6372-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Community perception and knowledge of cystic echinococcosis in the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco Séverine Thys1,2* , Hamid Sahibi3, Sarah Gabriël4, Tarik Rahali5, Pierre Lefèvre6, Abdelkbir Rhalem3, Tanguy Marcotty7, Marleen Boelaert1 and Pierre Dorny8,2 Abstract Background: Cystic echinococcosis (CE), a neglected zoonosis caused by the larval stage of the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus, remains a public health issue in many developing countries that practice extensive sheep breeding. Control of CE is difficult and requires a community-based integrated approach. We assessed the communities’ knowledge and perception of CE, its animal hosts, and its control in a CE endemic area of the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco. Methods: We conducted twenty focus group discussions (FGDs) stratified by gender with villagers, butchers and students in ten Berber villages that were purposefully selected for their CE prevalence. Results: This community considers CE to be a severe and relatively common disease in humans and animals but has a poor understanding of the parasite’s life cycle. Risk behaviour and disabling factors for disease control are mainly related to cultural practices in sheep breeding and home slaughtering, dog keeping, and offal disposal at home, as well as in slaughterhouses. Participants in our focus group discussions were supportive of control measures as management of canine populations, waste disposal, and monitoring of slaughterhouses. Conclusions: The uncontrolled stray dog population and dogs having access to offal (both at village dumps and slaughterhouses) suggest that authorities should be more closely involved in CE control. -

2009 MENA-OECD Ministerial Conference Registered Participants

2009 MENA-OECD Ministerial Conference Registered Participants Representing Algérie Mr. Abderrahmane ABEDOU Directeur de Recherche CREAD Ministère de l’enseignement supérieur et de la recherché scientifique (Algérie) Allemagne H.E. Dr. Ulf-Dieter KLEMM Ambassador German Embassy in Morocco Mr. MARCO WIEDEMANN Directeur Général Chambre Allemande Mr. Peter JUNGEN President European Enterprise Institute Arabie Saoudite H.E. Dr. Hamad S. AL-BAZAI Vice Minister of Finance Ministry of Finance Dr. KARAOUI First Secretary Embassy of Saudi Arabia to Morocco Australie H.E. Mr. Christopher LANGMAN Ambassador, Permanent Representative of Delegation of Australia to the Australia to the OECD OECD 03 December 2009 Page 1 sur 100 Representing Autorité Palestinienne H.E. Dr. Ali JARBAWI Minister of Planning and Administrative Ministry of Planning and Development Administrative Development Mr. Jafar HDAIB Director general, Palestine Investment Palestine Investment Promotion Agency Promotion Agency Mr. Baha’ BAKRI Special Advisor to the Minister Ministry of Planning and Administrative Development Mr. John KHOURY Director European Palestinian Credit Guarantee Fund Mr. Mahmoud SHAHEEN Deputy Head General Personnel Council Dr. Khaled Raji ZEIDAN Governance Policy Advisor Ministry of Planning and Ministry of Planning and Administrative Development 03 December 2009 Page 2 sur 100 Representing Bahreïn H.E. Sheikh Mohammed bin Essa AL KHALIFA Chief Executive, Economic Development Economic Development Board Board Mrs. Waheeda AL DOY Director MENA Centre for Investment Mrs. Muneera AL KHALIFA Director of Elections and Referendom - Ministry of Justice and Islamic Acting Director of Cases Affairs Mr. Mohammed ALSHOMALI Lawyer Mr. Abdulla BAQER Head of Primary Sector Development Ministry of Health (Fisheries) Mr. Rashid A.R ISHAQ Advisor, Good Governance Civil Service Bureau Miss Hana KANOO Senior Economist MENA Centre for Investment Mrs.