Community Perception and Knowledge of Cystic Echinococcosis in the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chief Liquidity Series

Chief Liquidity Series Water-related materiality briefings for financial institutions Issue 2 • September 2010 Power Sector Geographies Australia Brazil India South Africa Mediterranean Basin (Morocco, Italy, Greece) Local guidance on a global issue A briefing series by the Water & Finance Work Stream of the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative Chief Liquidity Series Water-related materiality briefings for financial institutions Issue 2 • September 2010 Power Sector Geographies Australia Brazil India South Africa Mediterranean Basin (Italy, Greece Morocco) Prepared for UNEP Finance Initiative by The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the United Nations Environment Programme in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. The United Nations Environment Programme does not warrant that the information contained in this publication is complete and correct and shall -

Design a Mobile Employment Agency for Me

Design a Mobile Employment Agency for Me Experiences and Lessons Learned for Scaling Up the Concept of Mobile Employment Agencies. December 2018 Réalisé par : Mis en œuvre par : « I have stressed[...] the need to place young people’s concerns at the heart of the new development model. I have also called for the development of an integrated strategy dedicated to young people, which would make it possible to defi ne ways of eff ectively advancing their status. » « In fact, socio-professional integration is not a privilege granted to young people. Every citizen, regardless of his or her background, has the right to the same opportunities and chances of access to quality education and decent employment. » « A comprehensive overhaul of public support systems and programs for youth employment must be undertaken to make them more eff ective and responsive to the expectations of young people. » Speech by H.M. King Mohammed VI on the occasion of the 65th anniversary of the Révolution du Roi et du Peuple. August 2018. Sommaire 1 - Introduction 07 2 - Scope 11 3 - Approach 15 I Am a Job-Seeker in Rural and Peri-Urban Areas (Empathy) 17 My Needs (Research) 25 Suggest Ideas and Alternatives for Me (Design) 26 Choosing the Right Prototype for Me (Prototype) 34 My First Experiences with Mobile Agencies (Sharing and Testing) 48 4 - Results and fi gure 55 Does It Work? 56 How Much Does It Cost? 58 5 - Recommendations 59 Management and Monitoring 60 Communicate, Communicate, Communicate 62 Checklist for Expansion 63 Appendices Appendix 1: Glossary of Terms -

Weathering Morocco's Syria Returnees | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 2148 Weathering Morocco's Syria Returnees by Vish Sakthivel Sep 25, 2013 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Vish Sakthivel Vish Sakthivel was a 2013-14 Next Generation Fellow at The Washington Institute. Brief Analysis The Moroccan government should be encouraged to adopt policies that preempt citizens from joining the Syrian jihad and deradicalize eventual returnees. ast week, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) released a video titled "Morocco: The Kingdom of Corruption L and Tyranny." In addition to pushing young Moroccans to join the jihad, the video inveighs against King Muhammad VI -- one of several public communiques in what appears to be an escalating campaign against the ruler. The timing of the video could not be more unsettling. A week before its release, against the backdrop of an increasingly insecure Sahel region, the government arrested several jihadist operatives in the northern cities of Fes, Meknes, and Taounate and the southern coastal town of Tiznit. Meanwhile, Moroccan fighters are traveling to Syria in greater numbers and forming their own jihadist groups, raising concerns about what they might do once they return home. VIDEO AND RESPONSE T he video released by al-Andalus, AQIM's media network, begins by outlining the king's alleged profiteering and corruption, citing WikiLeaks and the nonfiction book Le Roi Predateur by Catherine Graciet and Eric Laurent. It then moves to the king's close friends Mounir Majidi and Fouad Ali el-Himma, accusing them of perpetuating monopolies and patronage networks that impoverish the country while allowing the king to become one of world's richest monarchs. -

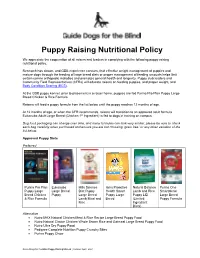

GDB Puppy Raising Nutritional Policy

Puppy Raising Nutritional Policy We appreciate the cooperation of all raisers and leaders in complying with the following puppy raising nutritional policy. Research has shown, and GDB experience concurs, that effective weight management of puppies and mature dogs through the feeding of large breed diets or proper management of feeding amounts helps limit certain canine orthopedic maladies and promotes general health and longevity. Puppy club leaders and Community Field Representatives (CFRs) will educate raisers on feeding puppies, and proper weight, and Body Condition Scoring (BCS) . At the GDB puppy kennel, prior to placement in a raiser home, puppies are fed Purina Pro Plan Puppy Large Breed Chicken & Rice Formula. Raisers will feed a puppy formula from the list below until the puppy reaches 12 months of age. At 12 months of age, or when the CFR recommends, raisers will transition to an approved adult formula. Eukanuba Adult Large Breed (Chicken 1st Ingredient) is fed to dogs in training on campus. Dog food packaging can change over time, and many formulas can look very similar; please be sure to check each bag carefully when purchased and ensure you are not choosing “grain free” or any other variation of the list below. Approved Puppy Diets Preferred Purina Pro Plan Eukanuba Hills Science Iams Proactive Natural Balance Purina One Puppy Large Large Breed Diet Puppy Health Smart Lamb and Rice Smartblend Breed Chicken Puppy Large Breed Puppy Large Puppy LID Large Breed & Rice Formula Lamb Meal and Breed (Limited Puppy Formula Rice Ingredient -

Orijen | Biological Food for Cats and Dogs

!"#"$%$&'()"'*"$"+$,%-.',/"" 0"#"&1/"2-/&$,)"%//23"'*"2'43"$%2"+$&3" 5"#"',-6/%"2/*-%/2"" 7"#"&1/"31',&"1-3&',)"'*"+'((/,+-$8"9/&"*''2" :"#"9,'&/-%";<$8-&)"" ="#"9,'&/-%";<$%&-&)"" >"#"+$,?'1)2,$&/"" "#",/*/,/%+/3"" 2. OMNIVORES have: o medium length digestive tracts giving them the ability to digest vegetation and animal proteins. o flat molars and sharp teeth developed for some grinding and some tearing, o the ability to eat either plants or animal proteins - but most often need both While the dog has been a companion to categories of food for complete nutrition. humans for at least 10,000 to 14,000 years, he is closest genetically to the wolf - differing only 1% or 2% in their gene sequences. 3. CARNIVORES have: o short, simple digestive tracts for Like wolves and lions - dogs and cats are digesting animal protein and fat. (dogs opportunistic carnivores that thrive on diets and cats fall into this category). that are almost exclusively meat-based, and with very few carbohydrates. o sharp, blade-shaped molars designed for slicing, rather than flat grinding molars designed for grinding. $%$&'(-+$8"2-**/,/%+/3"#" o jaws that cannot move sideways (unlike 1/,?-.',/3!"'(%-.',/3!" herbivores and omnivores that grind +$,%-.',/3" their food by chewing) and are hinged to open widely to swallow large chunks of meat whole. The anatomical specialization of dogs and cats to a meat based diet can be seen in the length of their gastro-intestinal tract, the development of their teeth and jaws, and +$,%-.',/3"#"/.'8./2"*'," their lack of digestive enzymes needed to (/$&" break down starch. To summarize, the anatomical features that define all carnivores are: 1. -

Proceedings of the Third International American Moroccan Agricultural Sciences Conference - AMAS Conference III, December 13-16, 2016, Ouarzazate, Morocco

Atlas Journal of Biology 2017, pp. 313–354 doi: 10.5147/ajb.2017.0148 Proceedings of the Third International American Moroccan Agricultural Sciences Conference - AMAS Conference III, December 13-16, 2016, Ouarzazate, Morocco My Abdelmajid Kassem1*, Alan Walters2, Karen Midden2, and Khalid Meksem2 1 Plant Genetics, Genomics, and Biotechnology Lab, Dept. of Biological Sciences, Fayetteville State University, Fayetteville, NC 28301, USA; 2 Dept. of Plant, Soil, and Agricultural Systems, Southern Illinois University, Car- bondale, IL 62901-4415, USA Received: December 16, 2016 / Accepted: February 1, 2017 Abstract ORAL PRESENTATIONS ABSTRACTS The International American Moroccan Agricultural Sciences WEDNESDAY & THURSDAY Conference (AMAS Conference; www.amas-conference.org) is an international conference organized by the High Council DECEMBER 14 & 15, 2016 of Moroccan American Scholars and Academics (HC-MASA; www.hc-masa.org) in collaboration with various universities I. SESSION I. DATE PALM I: ECOSYSTEM’S PRESENT and research institutes in Morocco. The first edition (AMAS AND FUTURE, MAJOR DISEASES, AND PRODUC- Conference I) was organized on March 18-19, 2013 in Ra- TION SYSTEMS bat, Morocco; AMAS Conference II was organized on October 18-20, 2014 in Marrakech, Morocco; and AMAS III was or- Co-Chair: Mohamed Baaziz, Professor, Cadi Ayyad University, ganized on December 13-16, 2016 in Ouarzazate, Morocco. Marrakech, Morocco The current proceedings summarizes abstracts from 62 oral Co-Chair: Ikram Blilou, Professor, Wageningen University & Re- presentations and 100 posters that were presented during search, The Netherlands AMAS Conference III. 1. Date Palm Adaptative Strategies to Desert Conditions Keywords: AMAS Conference, HC-MASA, Agricultural Sciences. Alejandro Aragón Raygoza, Juan Caballero, Xiao, Ting Ting, Yanming Deng, Ramona Marasco, Daniele Daffonchio and Ikram Blilou*. -

Morocco and United States Combined Government Procurement Annexes

Draft Subject to Legal Review for Accuracy, Clarity, and Consistency March 31, 2004 MOROCCO AND UNITED STATES COMBINED GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT ANNEXES ANNEX 9-A-1 CENTRAL LEVEL GOVERNMENT ENTITIES This Chapter applies to procurement by the Central Level Government Entities listed in this Annex where the value of procurement is estimated, in accordance with Article 1:4 - Valuation, to equal or exceed the following relevant threshold. Unless otherwise specified within this Annex, all agencies subordinate to those listed are covered by this Chapter. Thresholds: (To be adjusted according to the formula in Annex 9-E) For procurement of goods and services: $175,000 [Dirham SDR conversion] For procurement of construction services: $ 6,725,000 [Dirham SDR conversion] Schedule of Morocco 1. PRIME MINISTER (1) 2. NATIONAL DEFENSE ADMINISTRATION (2) 3. GENERAL SECRETARIAT OF THE GOVERNMENT 4. MINISTRY OF JUSTICE 5. MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND COOPERATION 6. MINISTRY OF THE INTERIOR (3) 7. MINISTRY OF COMMUNICATION 8. MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION, EXECUTIVE TRAINING AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH 9. MINISTRY OF NATIONAL EDUCATION AND YOUTH 10. MINISTRYOF HEALTH 11. MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND PRIVATIZATION 12. MINISTRY OF TOURISM 13. MINISTRY OF MARITIME FISHERIES 14. MINISTRY OF INFRASTRUCTURE AND TRANSPORTATION 15. MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT (4) 16. MINISTRY OF SPORT 17. MINISTRY REPORTING TO THE PRIME MINISTER AND CHARGED WITH ECONOMIC AND GENERAL AFFAIRS AND WITH RAISING THE STATUS 1 Draft Subject to Legal Review for Accuracy, Clarity, and Consistency March 31, 2004 OF THE ECONOMY 18. MINISTRY OF HANDICRAFTS AND SOCIAL ECONOMY 19. MINISTRY OF ENERGY AND MINING (5) 20. -

Community Perception and Knowledge of Cystic Echinococcosis in the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco

Thys et al. BMC Public Health (2019) 19:118 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6372-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Community perception and knowledge of cystic echinococcosis in the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco Séverine Thys1,2* , Hamid Sahibi3, Sarah Gabriël4, Tarik Rahali5, Pierre Lefèvre6, Abdelkbir Rhalem3, Tanguy Marcotty7, Marleen Boelaert1 and Pierre Dorny8,2 Abstract Background: Cystic echinococcosis (CE), a neglected zoonosis caused by the larval stage of the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus, remains a public health issue in many developing countries that practice extensive sheep breeding. Control of CE is difficult and requires a community-based integrated approach. We assessed the communities’ knowledge and perception of CE, its animal hosts, and its control in a CE endemic area of the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco. Methods: We conducted twenty focus group discussions (FGDs) stratified by gender with villagers, butchers and students in ten Berber villages that were purposefully selected for their CE prevalence. Results: This community considers CE to be a severe and relatively common disease in humans and animals but has a poor understanding of the parasite’s life cycle. Risk behaviour and disabling factors for disease control are mainly related to cultural practices in sheep breeding and home slaughtering, dog keeping, and offal disposal at home, as well as in slaughterhouses. Participants in our focus group discussions were supportive of control measures as management of canine populations, waste disposal, and monitoring of slaughterhouses. Conclusions: The uncontrolled stray dog population and dogs having access to offal (both at village dumps and slaughterhouses) suggest that authorities should be more closely involved in CE control. -

Chapter 12 RABIES and CONTINUED MILITARY CONCERNS

Rabies and Continued Military Concerns Chapter 12 RABIES AND CONTINUED MILITARY CONCERNS NICOLE CHEVALIER, DVM, MPH,* AND KARYN HAVAS, DVM, PhD† INTRODUCTION A Historical Perspective The US Military’s Involvement ETIOLOGY AND EPIDEMIOLOGY Rabies Virus Variants and Distribution Rabies-free Definition and Areas Rabies Transmission Process and Conditions CLINICAL REVIEW Clinical Signs of Rabies in Animals Diagnosis of Rabies in Animals Animal Management After Bites from Rabies Suspects Human Postexposure Treatment for Rabies PREVENTION AND CONTROL Animal Vaccination Human Vaccination Military Animal Bite Reports Surveillance RABIES IN AN OPERATIONAL ENVIRONMENT Difficulties Posed by Certain Animal Populations Stray Animal Control Efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq Global Lessons Learned About Stray Animal Control Measures INTERNATIONALLY SUPPORTED RABIES CONTROL PROGRAMS Rabies Surveillance Mass Parenteral Vaccination Oral Vaccination Population Management Euthanasia Human Preexposure Vaccination Human Postexposure Prophylaxis RABIES CONTROL IN FUTURE CONTIGENCY OPERATIONS SUMMARY *Lieutenant Colonel, Veterinary Corps, US Army; Veterinary Capabilities Developer, Directorate of Combat and Doctrine Development, 2377Greeley Road, Building 4011, Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston, Texas 78234 †Major, Veterinary Corps, US Army; Veterinary Epidemiologist, US Army Public Health Command, Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, 503 Robert Grant Avenue, Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 345 Military Veterinary Services INTRODUCTION A Historical Perspective -

Feasibility Study on Water Resources Development in Rural Area Inthe Kingdom of Morocco

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY THE GOVERNMENT OF THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO FEASIBILITY STUDY ON WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT IN RURAL AREA INTHE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO FINAL REPORT VOLUME V SUPPORTING REPORT (2.B) FEASIBILITY STUDY AUGUST, 2001 JOINT VENTURE OF NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. AND NIPPON GIKEN INC. LIST OF FINAL REPORT VOLUMES Volume I: Executive Summary Volume II: Main Report Volume III: Supporting Report (1) Basic Study Supporting Report I: Geology Supporting Report II: Hydrology and Flood Mitigation Supporting Report III: Socio-economy Supporting Report IV: Environmental Assessment Supporting Report V: Soils, Agriculture and Irrigation Supporting Report VI: Existing Water Resources Development Supporting Report VII: Development Scale of the Projects Supporting Report VIII: Project Evaluation and Prioritization Volume IV: Supporting Report (2.A) Feasibility Study Supporting Report IX: Aero-Photo and Ground Survey Supporting Report X: Geology and Construction Material Supporting Report XI: Hydro-meteorology and Hydro-geology Supporting Report XII: Socio-economy Supporting Report XIII: Soils, Agriculture and Irrigation Volume V: Supporting Report (2.B) Feasibility Study Supporting Report XIV: Water Supply and Electrification Supporting Report XV: Determination of the Project Scale and Ground Water Recharging Supporting Report XVI: Natural and Social Environment and Resettlement Plan Supporting Report XVII: Preliminary Design and Cost Estimates Supporting Report XVIII: Economic and Financial Evaluation Supporting Report XIX: Implementation Program Volume VI: Drawings for Feasibility Study Volume VII: Data Book Data Book AR: Aero-Photo and Ground Survey Data Book GC: Geology and Construction Materials Data Book HY: Hydrology Data Book SO: Soil Survey Data Book NE: Natural Environment Data Book SE: Social Environment Data Book EA: Economic Analysis The cost estimate is based on the price level and exchange rate of April 2000. -

Pet Foods: How to Read Labels Lisa K

® ® KFSBOPFQVLCB?O>PH>¨ FK@LIKUQBKPFLK KPQFQRQBLCDOF@RIQROB>KA>QRO>IBPLRO@BP KLTELT KLTKLT G1960 Pet Foods: How to Read Labels Lisa K. Karr-Lilienthal, Extension Companion Animal Specialist “Chicken and Potato Formula.” These diets and any that clarify A diet is as important for pets as people. Under the product as a dinner, supper, platter, or entrée must contain standing the pet food label can help you feed your pet at least 25 percent of the named ingredients. This rule includes an appropriate diet. both plant and animal origin ingredients listed in the product name. Ingredients listed must be listed in order from highest Choosing the right pet food may be something a pet quantity to lowest quantity, and a minimum of 3 percent of owner gives only a passing thought at the grocery store or it each ingredient listed must be included in the diet. may be a decision that’s extensively researched. Either way, Another example of how ingredients are included in the when selecting a food that is right for a particular companion pet food’s name is one labeled “Dog Food With Beef.” Any animal, read the pet food label carefully before buying. Label ingredient listed after the word “with” must be included at a items can be confusing, but when you know what to look for, minimum level of 3 percent of the diet. This type of pet food selecting the right pet food becomes much easier. name is seen frequently on canned foods. Some products may In order to evaluate the label information, look at the label say “Beef Flavored Dog Food.” In these cases, the diet must in two parts: the principal display panel (front of the label) and only contain a source of the flavor that is detectable whether the information panel (immediately to the right of the principal it is from the ingredient itself or a flavor enhancer. -

11892452 02.Pdf

Table of Contents A: SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CONDITIONS B: WATER LEVEL FLUCTUATION AND GEOLOGICAL CROSS SECTION IN THE HAOUZ PLAIN C: CLIMATE, HYDROLOGY AND SURFACE WATER RESOURCES D: IRRIGATION E: SEWERAGE AND WATER QUALITY F: WATER USERS ASSOCIATIONS AND FARM HOUSEHOLD SURVEY G: GROUNDWATER MODELLING H: STAKEHOLDER MEETINGS - i - A: SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CONDITIONS Table of Contents A: SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CONDITIONS A.1 Social and Economic Conditions of the Country ------------------------------------------ A - 1 A.1.1 Administration------------------------------------------------------------------------- A - 1 A.1.2 Social Conditions ------------------------------------------------------------------------ A - 1 A.1.3 Economic Conditions----------------------------------------------------------------- A - 2 A.1.4 National Development Plan ------------------------------------------------------------ A - 3 A.1.5 Privatization and Restructuring of Public Utilities ------------------------------- A - 5 A.1.6 Environmental Policies--------------------------------------------------------------- A - 6 A.2 Socio-Economic Conditions in the Study Area -------------------------------------------- A - 8 A.2.1 Social and Economic Situations----------------------------------------------------- A - 8 A.2.2 Agriculture ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- A - 9 A.2.3 Tourism--------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A - 11 A.2.4 Other Industries-----------------------------------------------------------------------