Chapter 12 RABIES and CONTINUED MILITARY CONCERNS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Most Effective Tool to Prevent Human Brucellosis

Chapter 13 Control of Animal Brucellosis — The Most Effective Tool to Prevent Human Brucellosis Marta Pérez-Sancho, Teresa García-Seco, Lucas Domínguez and Julio Álvarez Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/61222 Abstract The World Health Organization classifies brucellosis as one of the seven neglected en‐ demic zoonosis which contribute to the perpetuation of poverty in developing coun‐ tries. Although most of the developed countries are free from this important zoonosis, brucellosis has still a widespread distribution in the Mediterranean region, the Middle East, Central Asia, and parts of Latin America, making it a global problem. Nearly half a million of new cases of human brucellosis are reported each year around the world, in which animals (or products of animal origin) are the most likely source of infection. Brucella melitensis, the main etiologic agent of small ruminant brucellosis, is the most prevalent specie involved in cases of human disease in most parts of the world. Additionally, Brucella abortus (main responsible of bovine brucellosis) and Bru‐ cella suis (the most common etiological agent of porcine brucellosis) are often associat‐ ed with human brucellosis. In animal production, brucellosis has a strong economic impact due not only to its direct consequences (e.g., reproductive failures) but also to indirect loses (e.g., trade restrictions). The problem of brucellosis could be considered a clear example of the need for a “One World, One Health” strategy, given that the only approach to achieve its control and subsequent eradication is the cooperation be‐ tween public and animal health authorities. -

Humanitarian Assistance for Wild Animals

Thoughts Humanitarian Assistance for Wild Animals Kyle Johannsen argues that most wild animals live bad lives, and we should intervene in nature to improve their wellbeing When you read the title of this paper, what ergy, and attract the attention of predators, likely comes to mind is images of Koala by singing for prolonged periods of time. bears being rescued from bush fires, or of Being encumbered isn’t good for peacocks, injured raccoons and deer, being rehabili- and exposing themselves to danger isn’t tated after a hurricane. These are examples good for songbirds. Rather, the function of of humanitarian assistance for wild animals, heavy feathers and prolonged singing, is to but they’re not what this paper is primar- protect the birds’ genes by attracting mates. ily about. The need for humanitarian as- Mating, and reproducing, may be enjoy- sistance in the wild far exceeds the damage able for these animals, but surely evolution caused by natural disasters. Severe suffering would have facilitated these goals some oth- is pervasive in nature. It’s built into natural er way if the purpose of evolved traits were processes, and thus it’s the norm rather than to benefit the animals who have them. the exception. Since the purpose of evolution is to protect genes, you’d think that a parent’s evolved traits at least function to benefit Severe suffering is her children. Unfortunately, protecting an pervasive in nature animals’ genes doesn’t always benefit her children either. After all, many animals are r-strategists: they protect their genes Many people think that evolution is an by producing large numbers of offspring. -

Using Cross-Species Vaccination Approaches to Counter Emerging

PERSPECTIVES adjuvant combinations to inform ‘go’ or ‘no- go’ decisions with regard to subsequent Using cross- species vaccination development of promising vaccine candidates (Fig. 1). approaches to counter emerging Most human infectious diseases have an animal origin, with more than 70% of infectious diseases emerging infectious diseases that affect humans initially crossing over from 8 George M. Warimwe , Michael J. Francis , Thomas A. Bowden, animals . Generating wider knowledge of how pathogens behave in animals can Samuel M. Thumbi and Bryan Charleston give indications of how to develop control Abstract | Since the initial use of vaccination in the eighteenth century, our strategies for human diseases, and vice understanding of human and animal immunology has greatly advanced and a wide versa. ‘One Health vaccinology’, a concept in which synergies in human and veterinary range of vaccine technologies and delivery systems have been developed. The immunology are identified and exploited COVID-19 pandemic response leveraged these innovations to enable rapid for vaccine development, could transform development of candidate vaccines within weeks of the viral genetic sequence our ability to control such emerging being made available. The development of vaccines to tackle emerging infectious infectious diseases. Due to similarities in diseases is a priority for the World Health Organization and other global entities. host–pathogen interactions, the natural More than 70% of emerging infectious diseases are acquired from animals, with animal hosts of a zoonotic infection may be the most appropriate model to study the some causing illness and death in both humans and the respective animal host. Yet disease and evaluate vaccine performance9. -

An Argument for Reclassifying Military Working Dogs As •Œcanine

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami National Security & Armed Conflict Law Review 4-1-2014 Don’t Let Slip the Dogs of War: An Argument for Reclassifying Military Working Dogs as “Canine Members of the Armed Forces” Michael J. Kranzler Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umnsac Part of the Military, War and Peace Commons, and the National Security Commons Recommended Citation Michael J. Kranzler, Don’t Let Slip the Dogs of War: An Argument for Reclassifying Military Working Dogs as “Canine Members of the Armed Forces”, 4 U. Miami Nat’l Security & Armed Conflict L. Rev. 268 (2014) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umnsac/vol4/iss1/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami National Security & Armed Conflict Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT NOTE Don’t Let Slip the DoGs of War: An ArGument for ReclassifyinG Military WorkinG DoGs as “Canine Members of the Armed Forces” Michael J. Kranzler ∗ Abstract Dogs have been an integral part of military activities around the world dating back more than two thousand years. They have fended off invasions and helped bring down one of the world’s most notorious terrorist leaders. Yet under current law, they are afforded nearly the same protections as a torn uniform or a jammed rifle, classified in the United States Code as “excess equipment.” Historically, this led to hundreds of dogs being euthanized each year because the United States had no legal obligation to bring this excess equipment home at the end of their deployments. -

Professional Guidance for Animal Bites and Rabies Control

December 6, 2004 MEMORANDUM TO: State Public Health Veterinarians State Epidemiologists State Veterinarians Other Parties Interested in Rabies Prevention and Control FROM: Mira J. Leslie, D.V.M., M.P.H, Co-Chair Compendium of Animal Rabies Prevention and Control Committee SUBJECT: Compendium of Animal Rabies Prevention and Control, 2005 The National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians (NASPHV) is pleased to provide the 2005 revision of the Compendium of Animal Rabies Prevention and Control for your use and for distribution to practicing veterinarians and officials in animal control, public health, wildlife management and agriculture in your state. This cover memo summarizes the changes that were made to the document this year. COMPENDIUM CHANGES The section Principles of Rabies Prevention and Control (formerly Part II) is now Part I of the document and Recommendations for Parenteral Rabies Vaccination Procedures is Part II. Part III: Rabies Vaccines Licensed and Marketed in the U.S., 2005 has been updated. The following feline combination vaccine products are no longer available: IMRAB 3 + Feline 3; IMRAB 3 +Feline 4; PUREVAX Feline 3/ Rabies+LEUCAT; ECLIPSE 3 + FeLV/R; ECLIPSE 4+FeLV/R; Fel-O-Guard 3+ FeLV/R; and Fel-O-Guard 4+FeLV/R. The definition of a rabies exposure in Part I.A.1. has been clarified and a new sentence is added to direct questions concerning possible rabies exposures to local and state public health authorities. During 2004, there were two recognized importations of rabid dogs into the United States, one from Puerto Rico (mongoose rabies variant that is readily transmitted dog-to-dog) and one from Thailand (canine rabies virus variant). -

GDB Puppy Raising Nutritional Policy

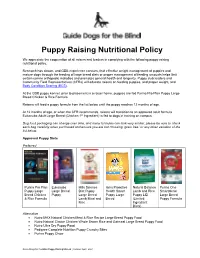

Puppy Raising Nutritional Policy We appreciate the cooperation of all raisers and leaders in complying with the following puppy raising nutritional policy. Research has shown, and GDB experience concurs, that effective weight management of puppies and mature dogs through the feeding of large breed diets or proper management of feeding amounts helps limit certain canine orthopedic maladies and promotes general health and longevity. Puppy club leaders and Community Field Representatives (CFRs) will educate raisers on feeding puppies, and proper weight, and Body Condition Scoring (BCS) . At the GDB puppy kennel, prior to placement in a raiser home, puppies are fed Purina Pro Plan Puppy Large Breed Chicken & Rice Formula. Raisers will feed a puppy formula from the list below until the puppy reaches 12 months of age. At 12 months of age, or when the CFR recommends, raisers will transition to an approved adult formula. Eukanuba Adult Large Breed (Chicken 1st Ingredient) is fed to dogs in training on campus. Dog food packaging can change over time, and many formulas can look very similar; please be sure to check each bag carefully when purchased and ensure you are not choosing “grain free” or any other variation of the list below. Approved Puppy Diets Preferred Purina Pro Plan Eukanuba Hills Science Iams Proactive Natural Balance Purina One Puppy Large Large Breed Diet Puppy Health Smart Lamb and Rice Smartblend Breed Chicken Puppy Large Breed Puppy Large Puppy LID Large Breed & Rice Formula Lamb Meal and Breed (Limited Puppy Formula Rice Ingredient -

Orijen | Biological Food for Cats and Dogs

!"#"$%$&'()"'*"$"+$,%-.',/"" 0"#"&1/"2-/&$,)"%//23"'*"2'43"$%2"+$&3" 5"#"',-6/%"2/*-%/2"" 7"#"&1/"31',&"1-3&',)"'*"+'((/,+-$8"9/&"*''2" :"#"9,'&/-%";<$8-&)"" ="#"9,'&/-%";<$%&-&)"" >"#"+$,?'1)2,$&/"" "#",/*/,/%+/3"" 2. OMNIVORES have: o medium length digestive tracts giving them the ability to digest vegetation and animal proteins. o flat molars and sharp teeth developed for some grinding and some tearing, o the ability to eat either plants or animal proteins - but most often need both While the dog has been a companion to categories of food for complete nutrition. humans for at least 10,000 to 14,000 years, he is closest genetically to the wolf - differing only 1% or 2% in their gene sequences. 3. CARNIVORES have: o short, simple digestive tracts for Like wolves and lions - dogs and cats are digesting animal protein and fat. (dogs opportunistic carnivores that thrive on diets and cats fall into this category). that are almost exclusively meat-based, and with very few carbohydrates. o sharp, blade-shaped molars designed for slicing, rather than flat grinding molars designed for grinding. $%$&'(-+$8"2-**/,/%+/3"#" o jaws that cannot move sideways (unlike 1/,?-.',/3!"'(%-.',/3!" herbivores and omnivores that grind +$,%-.',/3" their food by chewing) and are hinged to open widely to swallow large chunks of meat whole. The anatomical specialization of dogs and cats to a meat based diet can be seen in the length of their gastro-intestinal tract, the development of their teeth and jaws, and +$,%-.',/3"#"/.'8./2"*'," their lack of digestive enzymes needed to (/$&" break down starch. To summarize, the anatomical features that define all carnivores are: 1. -

Assembly Resolution No. 306 M. of A. Manktelow BY: May 16-22, 2021, As

Assembly Resolution No. 306 BY: M. of A. Manktelow RECOGNIZING May 16-22, 2021, as Military Animal Appreciation Week, and to honor these animals for their service WHEREAS, A generally overlooked part of our armed forces are the military animals which stand with and alongside our brave, enlisted men and women; and WHEREAS, Some of these courageous military animals include dogs, dolphins, rats, mules, donkeys, and pigeons; and WHEREAS, This Legislative Body is justly proud to recognize May 16-22, 2021, as Military Animal Appreciation Week, and to honor these animals for their service; and WHEREAS, Military canines are the most widely used military animal; dogs have served in combat alongside United States soldiers during every major conflict since the birth of our Nation; dogs were mostly used as message carriers and sentries during the first few conflicts, however, these days, they are trained to perform a wide-range of highly-specialized tasks; and WHEREAS, Modern military dogs are trained to sniff out bombs and drugs, track people, and even attack when necessary; there are about 2,500 war dogs in service today, with about 700 serving at any given time overseas; and WHEREAS, The United States military branches use marine mammals in a variety of ways; overseen by the Navy Marine Mammal Program, dolphins use their evolved sonar to detect underwater mines; and WHEREAS, Due to their exceptional underwater vision, the Navy Marine Mammal Program also uses sea lions to find potential enemy swimmers near piers and ships and draw attention to them; -

SEARG Report 2001

W. H. O. PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOUTHERN AND EASTERN AFRICAN RABIES GROUP / WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION MEETING SUDAN ERITREA ETHIOPIA UGANDA RWANDA KENYA BURUNDI TANZANIA MALAWI ZAMBIA MOZAMBIQUE ZIMBABWE MADAGASCAR BOTSWANA NAMIBIA SWAZILAND LESOTHO SOUTH AFRICA LILONGWE, MALAWI – 18-22 JUNE 2001 Sixth SEARG meeting, Lilongwe 18-21 June 2001 Official opening CONTENTS OFFICIAL OPENING PROGRAMME OF THE MEETING .............................................................................................................................. 4 Southern and Eastern African Rabies Group conference Lilongwe MALAWI: 18 to 21 June 2001 ................... 4 OPENING SPEECH................................................................................................................................................... 7 OPENING SPEECH................................................................................................................................................... 9 OPENING SPEECH................................................................................................................................................. 10 COUNTRY REPORTS RABIES IN BOTSWANA......................................................................................................................................... 13 RABIES IN BURUNDI IN 1999 AND 2000............................................................................................................... 17 RABIES IN ERITREA ............................................................................................................................................ -

1 WORLD SMALL ANIMAL VETERINARY ASSOCIATION 2015 VACCINATION GUIDELINES for the OWNERS and BREEDERS of DOGS and CATS WSAVA Vacci

WORLD SMALL ANIMAL VETERINARY ASSOCIATION 2015 VACCINATION GUIDELINES FOR THE OWNERS AND BREEDERS OF DOGS AND CATS WSAVA Vaccination Guidelines Group M.J. Day (Chairman) School of Veterinary Sciences University of Bristol, United Kingdom M.C. Horzinek (Formerly) Department of Microbiology, Virology Division University of Utrecht, the Netherlands R.D. Schultz Department of Pathobiological Sciences University of Wisconsin-Madison, United States of America R. A. Squires James Cook University, Queensland, Australia 1 CONTENTS Introduction.......................................................................................3 Major infectious diseases of the dog and cat....................................5 The immune response......................................................................21 The principle of vaccination..............................................................29 Types of vaccine...............................................................................32 Drivers for change in vaccination protocols......................................35 Canine vaccination guidelines..........................................................37 Feline vaccination guidelines…………………………………………..46 Reporting of adverse reactions.........................................................51 Glossary of terms..............................................................................57 2 INTRODUCTION Vaccination of dogs and cats protects them from infections that may be lethal or cause serious disease. Vaccination is a safe and efficacious -

Pet Foods: How to Read Labels Lisa K

® ® KFSBOPFQVLCB?O>PH>¨ FK@LIKUQBKPFLK KPQFQRQBLCDOF@RIQROB>KA>QRO>IBPLRO@BP KLTELT KLTKLT G1960 Pet Foods: How to Read Labels Lisa K. Karr-Lilienthal, Extension Companion Animal Specialist “Chicken and Potato Formula.” These diets and any that clarify A diet is as important for pets as people. Under the product as a dinner, supper, platter, or entrée must contain standing the pet food label can help you feed your pet at least 25 percent of the named ingredients. This rule includes an appropriate diet. both plant and animal origin ingredients listed in the product name. Ingredients listed must be listed in order from highest Choosing the right pet food may be something a pet quantity to lowest quantity, and a minimum of 3 percent of owner gives only a passing thought at the grocery store or it each ingredient listed must be included in the diet. may be a decision that’s extensively researched. Either way, Another example of how ingredients are included in the when selecting a food that is right for a particular companion pet food’s name is one labeled “Dog Food With Beef.” Any animal, read the pet food label carefully before buying. Label ingredient listed after the word “with” must be included at a items can be confusing, but when you know what to look for, minimum level of 3 percent of the diet. This type of pet food selecting the right pet food becomes much easier. name is seen frequently on canned foods. Some products may In order to evaluate the label information, look at the label say “Beef Flavored Dog Food.” In these cases, the diet must in two parts: the principal display panel (front of the label) and only contain a source of the flavor that is detectable whether the information panel (immediately to the right of the principal it is from the ingredient itself or a flavor enhancer. -

Community Perception and Knowledge of Cystic Echinococcosis in the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco

Thys et al. BMC Public Health (2019) 19:118 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6372-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Community perception and knowledge of cystic echinococcosis in the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco Séverine Thys1,2* , Hamid Sahibi3, Sarah Gabriël4, Tarik Rahali5, Pierre Lefèvre6, Abdelkbir Rhalem3, Tanguy Marcotty7, Marleen Boelaert1 and Pierre Dorny8,2 Abstract Background: Cystic echinococcosis (CE), a neglected zoonosis caused by the larval stage of the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus, remains a public health issue in many developing countries that practice extensive sheep breeding. Control of CE is difficult and requires a community-based integrated approach. We assessed the communities’ knowledge and perception of CE, its animal hosts, and its control in a CE endemic area of the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco. Methods: We conducted twenty focus group discussions (FGDs) stratified by gender with villagers, butchers and students in ten Berber villages that were purposefully selected for their CE prevalence. Results: This community considers CE to be a severe and relatively common disease in humans and animals but has a poor understanding of the parasite’s life cycle. Risk behaviour and disabling factors for disease control are mainly related to cultural practices in sheep breeding and home slaughtering, dog keeping, and offal disposal at home, as well as in slaughterhouses. Participants in our focus group discussions were supportive of control measures as management of canine populations, waste disposal, and monitoring of slaughterhouses. Conclusions: The uncontrolled stray dog population and dogs having access to offal (both at village dumps and slaughterhouses) suggest that authorities should be more closely involved in CE control.