Dairying in Malabar: a Venture of the Landowning Based on Women's Work?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rticulars of Organization, Function and Duties of Passport Office, Kozhikode

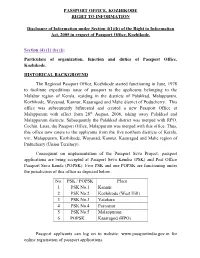

PASSPORT OFFICE, KOZHIKODE RIGHT TO INFORMATION Disclosure of Information under Section 4(1)(b) of the Right to Information Act, 2005 in respect of Passport Office, Kozhikode. Section (4) (1) (b) (i): Particulars of organization, function and duties of Passport Office, Kozhikode. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The Regional Passport Office, Kozhikode started functioning in June, 1978 to facilitate expeditious issue of passport to the applicants belonging to the Malabar region of Kerala, residing in the districts of Palakkad, Malappuram, Kozhikode, Wayanad, Kannur, Kasaragod and Mahe district of Puducherry. This office was subsequently bifurcated and created a new Passport Office at Malappuram with effect from 28th August, 2006, taking away Palakkad and Malappuram districts. Subsequently the Palakkad district was merged with RPO, Cochin. Later, the Passport Office, Malappuram was merged with this office. Thus, this office now caters to the applicants from the five northern districts of Kerala, viz., Malappuram, Kozhikode, Wayanad, Kannur, Kasaragod and Mahe region of Puducherry (Union Territory). Consequent on implementation of the Passport Seva Project, passport applications are being accepted at Passport Seva Kendra (PSK) and Post Office Passport Seva Kenda (POPSK). Five PSK and one POPSK are functioning under the jurisdiction of this office as depicted below. No. PSK / POPSK Place 1 PSK No.1 Kannur 2 PSK No.2 Kozhikode (West Hill) 3 PSK No.3 Vatakara 4 PSK No.4 Payyanur 5 PSK No.5 Malappuram 6 POPSK Kasaragod (HPO) Passport applicants can log on to website: www.passportindia.gov.in for online registration of passport applications. ORGANISATION CHART The Regional Passport Office, Kozhikode has a total of 80 staff as depicted below: Sl.No. -

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT History Ponnani Is Popularly Known As “The Mecca of Kerala”

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT HISTORY Ponnani is popularly known as “the Mecca of Kerala”. As an ancient harbour city, it was a major trading hub in the Malabar region, the northernmost end of the state. There are many tales that try to explain how the place got its name. According to one, the prominent Brahmin family of Azhvancherry Thambrakkal once held sway over the land. During their heydays, they offered ponnu aana [elephants made of gold] to the temples, and this gave the land the name “Ponnani”. According to another, due to trade, ponnu [gold] from the Arab lands reached India for the first time at this place, and thus caused it to be named “Ponnani”. It is believed that a place that is referred to as “Tyndis” in the Greek book titled Periplus of the Erythraean Sea is Ponnani. However historians have not been able to establish the exact location of Tyndis beyond doubt. Nor has any archaeological evidence been recovered to confirm this belief. Politically too, Ponnani had great importance in the past. The Zamorins (rulers of Calicut) considered Ponnani as their second headquarters. When Tipu Sultan invaded Kerala in 1766, Ponnani was annexed to the Mysore kingdom. Later when the British colonized the land, Ponnani came under the Bombay Province for a brief interval of time. Still later, it was annexed Malabar and was considered part of the Madras Province for one-and-a-half centuries. Until 1861, Ponnani was the headquarters of Koottanad taluk, and with the formation of the state of Kerala in 1956, it became a taluk in Palakkad district. -

Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (Scsp) 2014-15

Government of Kerala SCHEDULED CASTE SUB PLAN (SCSP) 2014-15 M iiF P A DC D14980 Directorate of Scheduled Caste Development Department Thiruvananthapuram April 2014 Planng^ , noD- documentation CONTENTS Page No; 1 Preface 3 2 Introduction 4 3 Budget Estimates 2014-15 5 4 Schemes of Scheduled Caste Development Department 10 5 Schemes implementing through Public Works Department 17 6 Schemes implementing through Local Bodies 18 . 7 Schemes implementing through Rural Development 19 Department 8 Special Central Assistance to Scheduled C ^te Sub Plan 20 9 100% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 21 10 50% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 24 11 Budget Speech 2014-15 26 12 Governor’s Address 2014-15 27 13 SCP Allocation to Local Bodies - District-wise 28 14 Thiruvananthapuram 29 15 Kollam 31 16 Pathanamthitta 33 17 Alappuzha 35 18 Kottayam 37 19 Idukki 39 20 Emakulam 41 21 Thrissur 44 22 Palakkad 47 23 Malappuram 50 24 Kozhikode 53 25 Wayanad 55 24 Kaimur 56 25 Kasaragod 58 26 Scheduled Caste Development Directorate 60 27 District SC development Offices 61 PREFACE The Planning Commission had approved the State Plan of Kerala for an outlay of Rs. 20,000.00 Crore for the year 2014-15. From the total State Plan, an outlay of Rs 1962.00 Crore has been earmarked for Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP), which is in proportion to the percentage of Scheduled Castes to the total population of the State. As we all know, the Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP) is aimed at (a) Economic development through beneficiary oriented programs for raising their income and creating assets; (b) Schemes for infrastructure development through provision of drinking water supply, link roads, house-sites, housing etc. -

The Political Economy of Agrarian Policies in Kerala: a Study of State Intervention in Agricultural Commodity Markets with Particular Reference to Dairy Markets

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF AGRARIAN POLICIES IN KERALA: A STUDY OF STATE INTERVENTION IN AGRICULTURAL COMMODITY MARKETS WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO DAIRY MARKETS VELAYUDHAN RAJAGOPALAN Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Ph D Department Of Government London School O f Economics & Political Science University O f London April 1993 UMI Number: U062852 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Disscrrlation Publishing UMI U062852 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 P ”7 <ü i o ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes the nature of State intervention in agricultural commodity markets in the Indian province of Kerala in the period 1960-80. Attributing the lack of dynamism in the agrarian sector to market imperfections, the Government of Kerala has intervened both directly through departmentally run institutions and indirectly through public sector corporations. The failure of both these institutional devices encouraged the government to adopt marketing co-operatives as the preferred instruments of market intervention. Co-operatives with their decentralised, democratic structures are^ in theory, capable of combining autonomous decision-making capacity with accountability to farmer members. -

MALAPPURAM DISTRICT College of Engg. Trivandrum Mohammed

MALAPPURAM DISTRICT College of engg. Trivandrum Mohammed Shajahan P COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ABDUL AZEEZ C Government Engineering College Thrissur ABDUL AZEEZ KT Federal Institute of Science and Technology Abdul Basith Government Engineering College, Wayanad Abdul Basith K GEC palakkad Abdul Mahroof N MEA Engineering college perinthalmanna ABDUL MAJID K T Gov. Engineering college kozhikode Abdul Muhsin v Mes college of engineering Abdul Rishad Mes college of engineering Abdul Rishad Malabar Polytechnic college, Kottakkal Abdul Vahid B. S MES COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING,KUTTIPPURAM ABDUL VARIS N FISAT Abhay Krishna SD Tkm college of engineering Abhijit k Nehru college of engineering and reasearch centre Abhijith uk MES CET, KUNNUKARA Abhimanyu ks TKM College Of Engineering, Kollam ABHIRAJ.P COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING KOTTARAKKARA ABHIRAM P COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING TRIVANDATUM ABHIRAM P jawaharlal college of engineering and technology Abhishek A S Sreepathy institute of Management and technology Abijith g GEC PALAKKAD ADARSH DAS N Lal Bahadur Shastri College of Engineering, ADARSH DAS.P Eranad Knowledge City Technical Campus Adhil Fuad M.E.S College Of Engineering Adhin Gopuj.A COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ADHINI ULLAS AK COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ADHINI ULLAS AK COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY VALANCHERI ADHINI ULLAS AK GOVERNMENT ENGINEERING COLLEGE THRISSUR ADITHYA KUMAR M S Al ameen engineering college Adnan mohamed ali College of Engineering Trivandrum Afnan Mohammed A Government engineering college idukki Aghil.P MESCE AHAMED SHAMZAD MK MEA Engineering College Perinthalmanna Ahammed Jouhar E T Mes engineering college kuttipuram Ahammed rasheek Government Engineering College Thrissur AHNAS P P Ncerc Ajay Anand C Govt. -

Kerala Institute of Tourism & Travel Studies [Kitts

KERALA INSTITUTE OF TOURISM & TRAVEL STUDIES [KITTS] Residency, Thycaud, Thiruvananthapuram, 695014 Ph. Nos. + 91 471 2324968, 2329539, 2339178 Fax 2323989 E mail: [email protected] www.kittsedu.org RERETENDER NOTICE RETENDERs are invited from travel agents for issuing Domestic flight tickets for National Responsible Tourism Conference scheduled from 25 Mar – 27 Mar 2017 at Kerala Institute of Tourism & Travel Studies, Thiruvananthapuram. The detailed specifications are annexed to the RETENDER document. Details are available in our website www.kittsedu.org. Last Date: 21.03.2017 Sd/- Director RERETENDER DOCUMENT KERALA INSTITUTE OF TOURISM & TRAVEL STUDIES THIRUVANANTHAPURAM -14 RERETENDER DOCUMENT : TRAVEL AGENTS FOR PROVIDING DOMESTIC FLIGHT TICKETS FOR THE NATIONAL RESPONSIBLE TOURISM CONFERENCE SCHEDULED FROM 25 MARCH – 27 MARCH 2017 AT KERALA INSTITUTE OF TOURISM & TRAVEL STUDIES, RESIDENCY, THYCAUD THIRUVANANTHAPURAM - 695014 RETENDER No: 492/ /KITTS/FLIGHT TICKETS /17-18 A. Introduction Kerala Institute of Tourism and Travel Studies (KITTS) impart quality education and training in the field of Travel and Tourism. The Institute, established in the year of 1988, caters to the manpower requirements of tourism industry by offering various courses directly benefiting the industry. The institute is an autonomous organization registered under the Travancore-Cochin Literary, Scientific and charitable societies Registration Act 1955 (Act 12 of 1955). KITTS, with its head quarters at the Residency Compound, Thycaud has two sub centres at Ernakulam and Thalasserry. B. Job Description Sealed RETENDERs in prescribed format are invited from reputed travel agents for providing domestic flight tickets for National Responsible Tourism Conference scheduled from 25 Mar – 27 Mar 2017 at Kerala institute of Tourism & Travel Studies, Thiruvananthapuram. -

List of Offices Under the Department of Registration

1 List of Offices under the Department of Registration District in Name& Location of Telephone Sl No which Office Address for Communication Designated Officer Office Number located 0471- O/o Inspector General of Registration, 1 IGR office Trivandrum Administrative officer 2472110/247211 Vanchiyoor, Tvpm 8/2474782 District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 2 (GL)Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471868 Thiruvananthapuram-695023 General Thiruvananthapuram District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 3 (Audit) Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471869 Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Audit Thiruvananthapuram Amaravila P.O , Thiruvananthapuram 4 Amaravila Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2234399 Pin -695122 Near Post Office, Aryanad P.O., 5 Aryanadu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0472-2851940 Thiruvananthapuram Kacherry Jn., Attingal P.O. , 6 Attingal Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2623320 Thiruvananthapuram- 695101 Thenpamuttam,BalaramapuramP.O., 7 Balaramapuram Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2403022 Thiruvananthapuram Near Killippalam Bridge, Karamana 8 Chalai Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2345473 P.O. Thiruvananthapuram -695002 Chirayinkil P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 9 Chirayinkeezhu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2645060 695304 Kadakkavoor, Thiruvananthapuram - 10 Kadakkavoor Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2658570 695306 11 Kallara Trivandrum Kallara, Thiruvananthapuram -695608 Sub Registrar 0472-2860140 Kanjiramkulam P.O., 12 Kanjiramkulam Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2264143 Thiruvananthapuram- 695524 Kanyakulangara,Vembayam P.O. 13 -

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

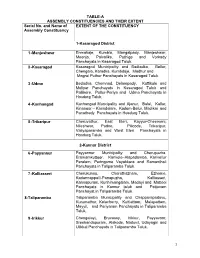

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Ground Water Information Booklet of Alappuzha District

TECHNICAL REPORTS: SERIES ‘D’ CONSERVE WATER – SAVE LIFE भारत सरकार GOVERNMENT OF INDIA जल संसाधन मंत्रालय MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES कᴂ द्रीय भजू ल बो셍 ड CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD केरल क्षेत्र KERALA REGION भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका, मलꥍपुरम स्ज쥍ला, केरल रा煍य GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, KERALA STATE तत셁वनंतपुरम Thiruvananthapuram December 2013 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, KERALA जी श्रीनाथ सहायक भूजल ववज्ञ G. Sreenath Asst Hydrogeologist KERALA REGION BHUJAL BHAVAN KEDARAM, KESAVADASAPURAM NH-IV, FARIDABAD THIRUVANANTHAPURAM – 695 004 HARYANA- 121 001 TEL: 0471-2442175 TEL: 0129-12419075 FAX: 0471-2442191 FAX: 0129-2142524 GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, KERALA TABLE OF CONTENTS DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 2.0 CLIMATE AND RAINFALL ................................................................................... 3 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND SOIL TYPES .............................................................. 4 4.0 GROUNDWATER SCENARIO ............................................................................... 5 5.0 GROUNDWATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY .............................................. 11 6.0 GROUNDWATER RELATED ISaSUES AND PROBLEMS ............................... 14 7.0 AWARENESS AND TRAINING ACTIVITY ....................................................... 14 -

Introduction

7 CHAPTER Introduction Over the last few months, the world economy has been showing alarming signs of fragility and instability. Economic growth has been sluggish with protracted unemployment, fiscal uncertainty and subdued business and consumer sentiments. Growth in high income countries is projected to be weak as they struggle to repair damaged financial sectors and badly stretched financial sheets. 1.2 Global economic growth started to decelerate on a broad front in mid-2011 and this trend is expected to stretch well into 2012 and 2013. The United Nations base line forecast for the growth of world gross product (WGP) is 2.6% for 2012 and 3.2% for 2013, which is below the pre-crisis pace of global growth. 1.3 It is expected that the US economy will grow at about 2% with modest growth in exports. Persistent high unemployment and low wage growth have been holding back aggregate demand and together with the prospects of prolonged depressed housing prices, this has heightened risks of a new wave of home foreclosures in the United States. However, employment data for December 2011 and January 2012 have been encouraging with signs of revival in business confidence. On the other hand, as far as the Euro Zone is concerned, high deficit and debt continue to prevail. The Euro Zone experienced a period of declining output, high unemployment and subdued private consumption. However, the business climate indicator increased for the first time in ten months and inflation rate fell from 3% to 2.8 % in December. In order to boost investment, the European Central Bank flooded banks with low cost loans and there was improvement in demand. -

Kerala Sustainable Urban Development Project

Government of Kerala Local Self Government Department Kerala Sustainable Urban Development Project (PPTA 4106 – IND) FINAL REPORT VOLUME 2 - CITY REPORT KOCHI MAY 2005 COPYRIGHT: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of ADB & Government of Kerala. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of either ADB or Government of Kerala constitutes an infringement of copyright. TA 4106 –IND: Kerala Sustainable Urban Development Project Project Preparation FINAL REPORT VOLUME 2 – CITY REPORT KOCHI Contents 1. BACKGROUND AND SCOPE 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Project Goal and Objectives 1 1.3 Study Outputs 1 1.4 Scope of the Report 1 2. CITY CONTEXT 2 2.1 Geography and Climate 2 2.2 Population Trends and Urbanization 2 2.3 Economic Development 2 2.3.1 Sectoral Growth 2 2.3.2 Industrial Development 6 2.3.3 Tourism Growth and Potential 6 2.3.4 Growth Trends and Projections 7 3. SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE 8 3.1 Introduction 8 3.2 Household Profile 8 3.2.1 Employment 9 3.2.2 Income and Expenditure 9 3.2.3 Land and Housing 10 3.2.4 Social Capital 10 3.2.5 Health 10 3.2.6 Education 11 3.3 Access to Services 11 3.3.1 Water Supply 11 3.3.2 Sanitation 11 3.3.3 Urban Drainage 12 3.3.4 Solid Waste Disposal 12 3.3.5 Roads, Street Lighting & Access to Public Transport 12 4. POVERTY AND VULNERABILITY 13 4.1 Overview 13 4.1.1 Employment 14 4.1.2 Financial Capital 14 4.1.3 Poverty Alleviation in Kochi 14 5. -

Panchayat/Municipality/Corp Oration

PMFBY List of Panchayats/Municipalities/Corporations proposed to be notified for Rabi II Plantain 2018-19 Season Insurance Unit Sl State District Taluka Block (Panchayat/Municipality/Corp Villages No oration) 1 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Kanjiramkulam All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 2 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Karimkulam All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 3 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Athiyanoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 4 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Kottukal All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 5 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Venganoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 6 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Kizhuvilam All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 7 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Mudakkal All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 8 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Anjuthengu All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 9 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Chirayinkeezhu All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 10 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Kadakkavoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 11 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Vakkom All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 12 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Kilimanoor Madavoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 13 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Kilimanoor Pallickal All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 14 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Kilimanoor Kilimanoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 15 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Kilimanoor Nagaroor All Villages