Oskar-Galewicz-Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arena Skatepark Dan Musik Indie

1 ARENA SKATEPARK DI YCGYAKARTA BAB2 Arena skatepark dan Musik Indie Skat.park dan pembahasannya 1. Skateboard dan pennainannya Skateboard adalah sualu permainan, yang dapat membcrikan suasana yang senang bagi pelakunya. Terlebih jika tempat kita bermain adalah tempat yang selafu memberikan nuansa baru; dalam hal ini adalah tempat yang dirasakan dapot memberikan variasi-variasi baru dalam bermain, dengan alat alat yang cenderung baru pula. Yang terjadi di luar negri (kasus di Amerika Serikat dan negara-negara Eropa), banyak tempat-tempat pUblik/area-area properti orang, yang sudah tertata secara arsitektural dengan baik; cenderung menjadi sasaran para pemain skateboard untuk dijadikan spot bermain skateboard. Dengan kecenderunyan bermain dijalanan, tentunya juga bakalan mengganggu keberadaan aktivitas yang lainnya. Tempat-tempat yang dibagian HAD' PURo..ICNC 9B 512 1 B6/ TUBAS AKHIR 16 I_~ ARENA SKATEPARK 01 YCGYAKARTA gedungnya terdapat ledge, handrail, tangga, dan obstacle-obstacle adalah sasoran yang selalu dijadikan tempat untuk bermain. Baik untuk dilompatL meluncur, ataupun untuk membenturkannya. Dengan demiklan kegiatan kegiotan ini sering dianggap illegal dan melawan hukum, korena merugikan dan cenderung merusak properti publik. Namun keberagaman spot di jalanan, terus dan terus mendorong para pemain skateboard untuk bertahan dan mencari spot-spot baru untuk dimainkan, dengan tetap beresiko ditangkap aparat keamanan. Kecenderungan gaya permainan street skateboarding inilah yang sekarang sedang menjadi trend di dunia skateboarding. Bermain di tempat yang selalu memberikan varias; komposisi obstacle yang selalu baru dan nuansa suasana baru, cenderung membuat pola permainan yang mengalir dan tidak membosankan. Kemenerusan trik yang dimainkan secara berurutan, dengan pola permainan yang mengalir dan didukung oleh komposisi alat yang tepat. Skatepark yang ada selama inL cenderung secara peruangan memberikan batasan antara ruang indoor dan outdoor. -

2017 SLS Nike SB World Tour and Only One Gets the Opportunity to Claim the Title ‘SLS Nike SB Super Crown World Champion’

SLS NIKE SB WORLD TOUR: MUNICH SCHEDULE SLS 2016 1 JUNE 24, 2017 OLYMPIC PARK MUNICH ABOUT SLS Founded by pro skateboarder Rob Dyrdek in 2010, Street League Skateboarding (SLS) was created to foster growth, popularity, and acceptance of street skateboarding worldwide. Since then, SLS has evolved to become a platform that serves to excite the skateboarding community, educate both the avid and casual fans, and empower communities through its very own SLS Foundation. In support of SLS’ mission, Nike SB joined forces with SLS in 2013 to create SLS Nike SB World Tour. In 2014, the SLS Super Crown World Championship became the official street skateboarding world championship series as sanctioned by the International Skateboarding Federation (ISF). In 2015, SLS announced a long-term partnership with Skatepark of Tampa (SPoT) to create a premium global qualification system that spans from amateur events to the SLS Nike SB Super Crown World Championship. The SPoT partnership officially transitions Tampa Pro into becoming the SLS North American Qualifier that gives one non-SLS Pros the opportunity to qualify to the Barcelona Pro Open and one non-SLS Pro will become part of the 2017 World Tour SLS Pros. Tampa Pro will also serve as a way for current SLS Pros to gain extra championship qualification points to qualify to the Super Crown. SLS is now also the exclusive channel for live streaming of Tampa Pro and Tampa Am. This past March, SLS Picks 2017, Louie Lopez, took the win at Tampa Pro, gaining him the first Golden Ticket of the year straight to Super Crown. -

Street Skateboarding Theory Simulation: Character Movement and Environment Meriyana Citrawati 0800766172

BINUS UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL BINUS UNIVERSITY Computer Science Major Multimedia Stream Sarjana Komputer Thesis Semester Even year 2008 Street Skateboarding Theory Simulation: Character Movement and Environment Meriyana Citrawati 0800766172 Abstract The objective of this thesis is to analyze the current learning media of street skateboarding, build a new skateboarding learning media using computer graphic software with 3D technology. To help people to learn skateboarding through a street skateboarding theory simulation, more than one viewing angle for learning skateboarding tricks and slow motion feature to aid users. The analysis of the current learning media and enthusiasts will be made by interviewing a pro skater and distribute questionnaire to all people both skaters and non skaters. From the questionnaires, pie charts will be used to explain the details of the current learning media and enthusiasts’ type. The results of the questionnaire will be used to create the street skateboarding theory simulation. The Waterfall method will be used to make a mock-up of the simulation so that the users could see and try out the simulation. The result of this thesis is that this Street Skateboarding Theory Simulation will be created as a new learning media to help people, both skater and non skater, in learning skateboarding tricks and also to solve problems of learning skateboard through other media. To conclude, this Street Skateboarding Theory Simulation is aimed to help people to learn street skateboarding. v Keywords: Skateboarding, Simulation, Computer graphic software, Waterfall method. vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, I would like to thank God that I can complete my education in BiNus. -

Design and Development Guidance for Skateboarding

Skateboarding Design and Development Guidance for Skateboarding Creating quality spaces and places to skateboard When referring to any documents and associated attachments in this guidance, please note the following:- 1. Reliance upon the guidance or use of the content of this website will constitute your acceptance of these conditions. 2. The term guidance should be taken to imply the standards and best practice solutions that are acceptable to Skateboard England. 3. The documents and any associated drawing material are intended for information only. 4. Amendments, alterations and updates of documents and drawings may take place from time to time and it’s recommended that they are reviewed at the time of use to ensure the most up-to-date versions are being referred to. 5. All downloadable drawings, images and photographs are intended solely to illustrate how elements of a facility can apply Skateboard England’s suggestions and should be read in conjunction with any relevant design guidance, British and European Standards, Health and Safety Legislation and guidance, building regulations, planning and the principles of the Equality Act 2010. 6. The drawings are not ‘site specific’ and are outline proposals. They are not intended for, and should not be used in conjunction with, the procurement of building work, construction, obtaining statutory approvals, or any other services in connection with building works. 7. Whilst every effort is made to ensure accuracy of all information, Skateboard England and its agents, including all parties who have made contributions to any documents or downloadable drawings, shall not be held responsible or be held liable to any third parties in respect of any loss, damage or costs of any nature arising directly or indirectly from reliance placed on this information without prejudice. -

1 How Skateboarding Made It to the Olympics

How skateboarding made it to the Olympics: an institutional perspective Dr Mikhail Batuev, Professor Leigh Robinson, Northumbria University University of Stirling [email protected] [email protected] Health and Life Sciences, Northumberland Building, Faculty of Health Sciences and Sport Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 8ST, UK. Pathfoot Building, Stirling, FK9 4LA, UK +44 (0) 191 227 3840 +44 (0) 1786466281 Abstract Utilizing new institutionalism and resource-dependency theory this paper examines the organisational context within which skateboarding has developed and is continuing to develop. As a radical lifestyle activity, many within the sport of skateboarding have sought to distance themselves from the institutionalized competitive structure exemplified by the modern Olympic Games, despite a steady growth in competitive skateboarding within increasingly formal structures. The aim of this paper is to explore how the sport has operationally evolved and how, as a major youth sport, Olympic inclusion has impacted on its organisational arrangements. Data were collected through a series of semi-structured interviews and supplemented by selected secondary sources including social media analysis, sport regulations and policy statements. The conclusions of the research are: 1) unlike many other sports, skateboarding has always functioned as a network which includes event organizers, media companies, and equipment producers, with governing bodies playing a more peripheral role; 2) there was a strong lobby from elite skateboarders in support of inclusion in the Olympics although only on ‘skateboarders terms’; 3) interest from the International Olympic Committee (IOC), which eventually led to the inclusion of skateboarding in the 2020 Olympic Games, has affected the organisational evolution of skateboarding over the last decade and has stressed issues of organisational legitimacy in this sport. -

Skateboarding スケートボード / Skateboard

Ver.1.0 5 AUG 2021 14:00 Version History Version Date Created by Comments 1.0 5 AUG José Alberto First 2021 Santacana Version Table of Contents Medallists by event Competition Format and Rules Course Design Entry List by NOC Women Men Women's Street Entry List by Event Heat Results - Prelims Results Summary Tie-Breaking protocol Medallists Men's Street Entry List by Event Heat Result - Prelims Result Summary Medallists Women's Park Entry List by Event Heat Results - Prelims Result Summary Medallists Men's Park Entry List by Event Heat Results - Prelims Result Summary Medallists Competition Officials Competition Schedule Skateboarding スケートボード / Skateboard Medallists by Event 種目別メダリスト / Médaillé(e)s par épreuve As of THU 5 AUG 2021 at 13:16 Event Date Medal Name NOC Code Women's Street 26 JUL 2021 GOLD NISHIYA Momiji JPN SILVER LEAL Rayssa BRA BRONZE NAKAYAMA Funa JPN Men's Street 25 JUL 2021 GOLD HORIGOME Yuto JPN SILVER HOEFLER Kelvin BRA BRONZE EATON Jagger USA Women's Park 4 AUG 2021 GOLD YOSOZUMI Sakura JPN SILVER HIRAKI Kokona JPN BRONZE BROWN Sky GBR Men's Park 5 AUG 2021 GOLD PALMER Keegan AUS SILVER BARROS Pedro BRA BRONZE JUNEAU Cory USA SKB-------------------------------_93 4 Report Created THU 5 AUG 2021 13:16 Page 1/1 Ariake Urban Sports Park Skateboarding 有明アーバンスポーツパーク スケートボード / Skateboard Parc de sports urbains d'Ariake Competition Format and Rules 競技形式および規則 / Format et règlement des compétitions As of THU 1 JUL 2021 Olympic Competition Format The Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games skateboarding competition consists of four events: • Women's street • Men's street • Women's park • Men's park Each event will be contested by 20 skaters, for a total of 40 female and 40 male skaters. -

Skateboarding

Skateboarding Design and Development Guidance for Skateboarding Creating quality spaces and places to skateboard When referring to any documents and associated attachments in this guidance, please note the following:- 1. Reliance upon the guidance or use of the content of this website will constitute your acceptance of these conditions. 2. The term guidance should be taken to imply the standards and best practice solutions that are acceptable to Skateboard GB. 3. The documents and any associated drawing material are intended for information only. 4. Amendments, alterations and updates of documents and drawings may take place from time to time and it’s recommended that they are reviewed at the time of use to ensure the most up-to-date versions are being referred to. 5. All downloadable drawings, images and photographs are intended solely to illustrate how elements of a facility can apply Skateboard GB’s suggestions and should be read in conjunction with any relevant design guidance, British and European Standards, Health and Safety Legislation and guidance, building regulations, planning and the principles of the Equality Act 2010. 6. The drawings are not ‘site specific’ and are outline proposals. They are not intended for, and should not be used in conjunction with, the procurement of building work, construction, obtaining statutory approvals, or any other services in connection with building works. 7. Whilst every effort is made to ensure accuracy of all information, Skateboard GB and its agents, including all parties who have made contributions to any documents or downloadable drawings, shall not be held responsible or be held liable to any third parties in respect of any loss, damage or costs of any nature arising directly or indirectly from reliance placed on this information without prejudice. -

Jan Holzers, Rvca European Brand Manager Local Skate Park Article Regional Market Intelligence Brand Profiles, Buyer Science & More

#87 JUNE / JULY 2017 €5 JAN HOLZERS, RVCA EUROPEAN BRAND MANAGER LOCAL SKATE PARK ARTICLE REGIONAL MARKET INTELLIGENCE BRAND PROFILES, BUYER SCIENCE & MORE RETAIL BUYER’S GUIDES: BOARDSHORTS, SWIMWEAR, SKATE FOOTWEAR, SKATE HARDGOODS, SKATE HELMETS & PROTECTION, THE GREAT OUTDOORS, HANGING SHOES ©2017 Vans, Inc. Vans, ©2017 Vans_Source87_Kwalks.indd All Pages 02/06/2017 09:41 US Editor Harry Mitchell Thompson [email protected] HELLO #87 Skate Editor Dirk Vogel Eco considerations were once considered a Show introducing a lifestyle crossover [email protected] luxury, however, with the rise of consumer section and in the States, SIA & Outdoor awareness and corporate social responsibility Retailer merging. Senior Snowboard Contributor the topic is shifting more and more into Tom Wilson-North focus. Accordingly, as the savvy consumer [email protected] strives to detangle themselves from the ties Issue 87 provides boardsports retail buyers of a disposable culture, they now require with all they need to know for walking the Senior Surf Contributor David Bianic fewer products, but made to a higher halls of this summer’s trade show season. It’s standard. Before, for example, a brand may with this in mind that we’re rebranding our [email protected] have intended for its jacket to be worn purely trend articles; goodbye Trend Reports, hello on the mountain, but now it’s expected to Retail Buyer’s Guides. As we battle through German Editor Anna Langer work in the snowy mountains, on a rainy information overload, it’s more important now [email protected] commute or for going fishing in. than ever before for retailers to trust their SOURCEs of information. -

The Skate Facility Guide by Sport and Recreation Victoria

Contents Disclaimer 2 Acknowledgements 3 Preface 4 Chapter 1: History 5 An overview of the evolution and further development of skating since the 1950s. Chapter 2: The market 9 The face of the skating market, skating trends and the economic value. Chapter 3: Encouragement 15 Why and how should we encourage skating? Chapter 4: The street 18 The challenges of skating in the streets. The challenges and strategies for a planned approach to street skating. Chapter 5: Planning 24 What is required in planning for a skate facility? Chapter 6: Design 44 Factors that need consideration in skate facility design. Chapter 7: Safety and risk 78 Danger factors in skating and suggested strategies to address risk and safety management at skate park facilities. Chapter 8: What skaters can do 93 Ideas for skaters to help develop a skate park. Chapter 9: Checklists Master copies of the main checklists appearing in the manual. Notes 101 References and citations made throughout the manual. Read on 103 Suggested further reading. The Skate Facility Guide 1 Disclaimer of responsibility The State of Victoria and its employees shall not be liable for any loss, damage, claim, costs, demands and expenses for any damage or injury of any kind whatsoever and howsoever arriving in connection with the use of this Skate Facility Guide or in connection with activities undertaken in recreation programs. As the information in this Skate Facility Guide is intended as a general reference source, employees of the State of Victoria and, in particular Sport and Recreation Victoria, have made every reasonable effort to ensure the information in this publication is current and accurate. -

Return to Form: Analyzing the Role of Media in Self-Documenting Subcultures

RETURN TO FORM: ANALYZING THE ROLE OF MEDIA IN SELF-DOCUMENTING SUBCULTURES GLEN WOOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO August 2020 © Glen Wood, 2020 Abstract This dissertation examines self-documenting subcultures and the role of media within three case studies: hardcore punk, skateboarding, and urban dirt-bike riding. The production and distribution of subcultural media is largely governed by intracultural industries. Elite practitioners and media-makers are incentivized to document performances that are deemed essential to the preservation of the status quo. This constructed dependency reflects and reproduces an ethos of conformity that pervades both social interactions and subcultural representations. Within each self-documenting subculture, media is the primary mode of socialization and representation. The production of media and meaning is constrained by the presence of prescriptive formal conventions propagated by elite producers. These conditions, in part, result in the institutionalization of conformity. The three case studies illustrate the theoretical and methodological framework that classifies these formations under a new typology. Accordingly, this dissertation introduces an alternative approach to the study of subcultures. ii Acknowledgments My academic career is based upon the support of numerous individuals, organizations, and institutions. I would like to thank John McCullough for his inspiring words and utter confidence in my work. Moreover, Markus Reisenleitner and Steve Bailey were integral throughout the dissertation process, encouraging my progress and providing their thoughtful commentary along the way. I am also greatly appreciative of the external reviewers for their time and evaluations. -

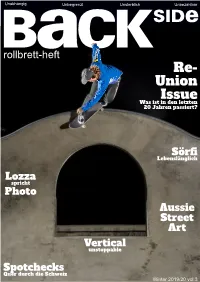

Side Rollbrett-Hefta Re- Union

Unabhängig Unbegrenzt Unsterblich Unbezahlbar B CKSIDe rollbrett-hefta Re- Union Was istIssue in den letzten 20 Jahren passiert? Sörfi Lebenslänglich Lozza spricht Photo Aussie Street Art Vertical unstoppable Spotchecks Quer durch die Schweiz Winter 2019/20 vol.3 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Forword We are Wer hätte das gedacht? Von einem Jahr noch unvorstellbar. Was ist passiert? Mitte der 90ier Jahren veranlasste mich ein derber gezogen sind und obwohl alle ziemlich verschieden Trennungsschmerz (die Geschichte ist Netflix das Rollbrett uns alle vereint hat. Sei das in St. serientauglich) meinen Wut, meine Energie und Gallen am Vadian, in Zürich auf der Landiewiese freie Zeit in ein Projekt zu investieren. Backside oder EMB in San Francisco. rollbrett-heft wurde geboren und als Nicole ‘Nikita’ Hecht mein erstes zusammengeklebtes Layout aus Von Rebellen kann heute wohl nicht mehr meinen Händen riss, wurde es richtig spannend. sprechen wenn ein Luxus Modelabel wie Armani mit Skateboarding wirbt, Tony Hawk im Jahr Millionen Zwei Ausgaben später verabschiedete ich mich verdient, SB-Foto/Videograph einen Oscar gewinnt, 1996 ins Ausland was auch das definitive ‘Aus’ür f ehemalige Skatepros in Spielfilmen zu sehen sind, Backside bedeutete. Nach der Rückkehr hatte ich erfolgreiche Modemarken aufbauen oder New den Appetit nach über 10 Jahren Skateboarding Balance ein Rider Team stellt (New Balance! verloren und bin sowieso gleich wieder in das Wirklich?). Was noch fehlt ist das Skateboarding als nächste Auslandabenteuer gestürzt. olympische Disziplin aufgenommen wird. 23 Jahre später melden wir uns zurück. Doch es gibt auch eine Backside, die wir mit unserem Unerwartet. In Farbe.Was ist den jetzt los? Schon ultimativen Re-Union Issue aufgreifen wollen. -

An Ethnolexicography of the Skateboarding Subculture

AN ETHNOLEXICOGRAPHY OF THE SKATEBOARDING SUBCULTURE By HO’OMANA NATHAN HORTON Bachelor of Arts in English Oklahoma Wesleyan University Bartlesville, OK 2013 Master of Arts in English Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK 2015 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY July, 2020 AN ETHNOLEXICOGRAPHY OF THE SKATEBOARDING SUBCULTURE Dissertation Approved: Dennis R. Preston Adviser Carol Moder Chair Nancy Caplow G. Allen Finchum ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work is dedicated to the memory of my grandfather, Hershall "Jigger" Horton, a true craftsman, who taught me that there are so many important, valuable skills and tools that can’t be learned in a classroom alone. And to Mrs. Carol Preston, the most welcoming and genuine person I think I've ever known, who always kept my desk well- stocked with humanitarian literature, and who cared so sincerely about everyone she met, and taught me to care for people and our planet more deeply every day. First and foremost, I want to thank my adviser, Dr. Dennis Preston, whose encouragement and mentorship have fueled this project from the start. When I started graduate school, I don't think I would ever have imagined I'd be writing a dissertation about skateboarding, but your genuine interest in this topic, and all that you've done to help me go beyond description and into a deeper understanding of language and society have enabled this work. I thank you also for bringing me on as a lab assistant in 2014 when I was just a grungy little skater with very little idea of what I was doing in academia.